Chronic pelvic pain (CPP) is defined in a variety of ways. The most commonly used definition of CPP considers only the location and duration of the pain: recurrent or constant pain in the lower abdominal region that has lasted for at least 6 months [

1]. Visceral pelvic pain is a common problem with variable etiology. The sympathetic nervous system plays an important role in the transmission of visceral pain regardless of its etiology. The autonomic sympathetic nervous system conveys nociceptive messages from the viscera to brain. In general, in order to block transmission of nociceptive information from the pelvic viscera to the spinal cord, interruption of sympathetic pathways will be necessary. The sympathetic nerve block on the sympathetic nervous system for the management of chronic pelvic pain has been proposed at main three levels: ganglion impar, hypogastric plexus and L2 lumbar sympathetic blocks. For the diagnosis and treatment of chronic pelvic pain conditions involving the lower pelvic viscera, blockage of the inferior hypogastric plexus has been introduced. A recent method of neurolytic inferior hypogastric plexus block via transsacral approach has several disadvantages because of transient paresthesia, nerve damage, rectal puncture, vascular penetration, hematoma, and infection [

2]. Since there has been no literature on the fluoroscopy-guided inferior hypogastric plexus block via coccygeal transverse approach, we report a successful inferior hypogastric plexus block via coccygeal transverse approach technique in a 65-year-old woman with chronic pelvic pain and coccygodynia.

CASE REPORT

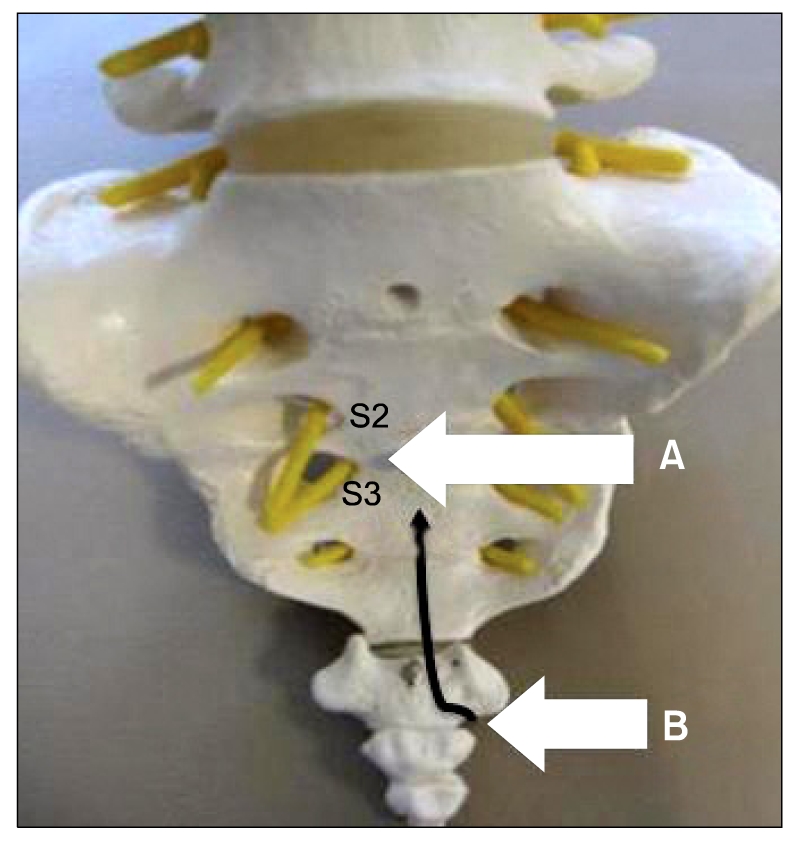

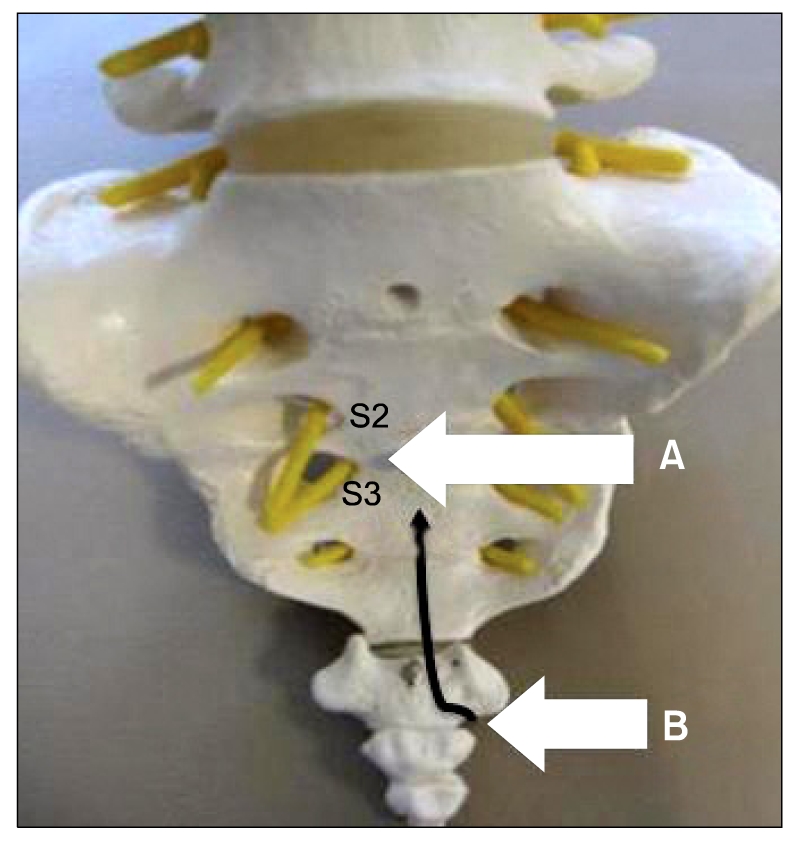

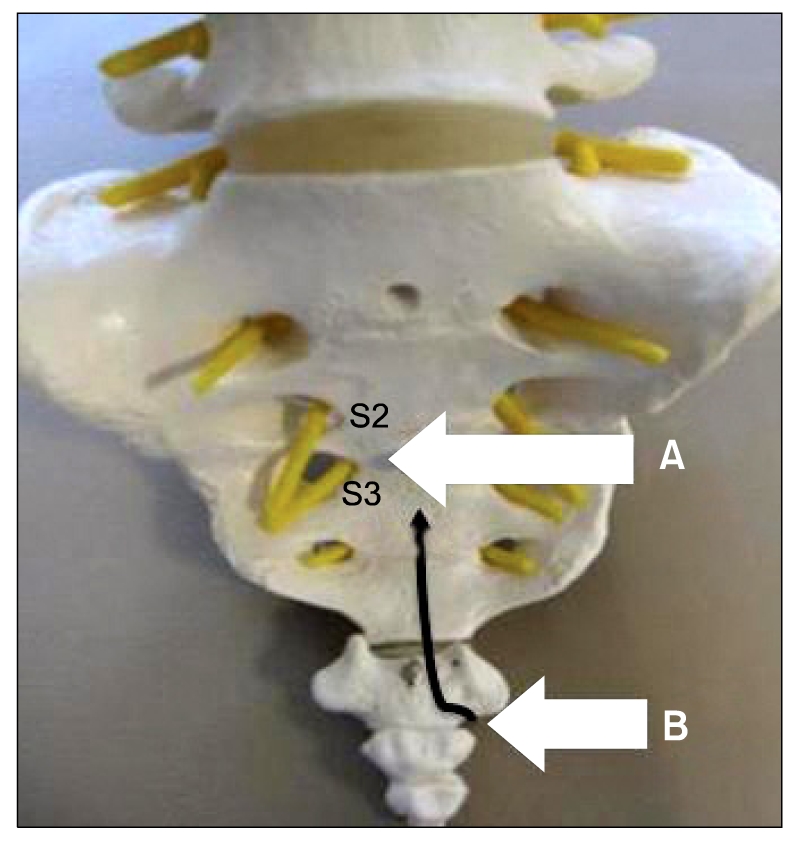

A 65-year-old woman complained of increasing pelvic pain and coccygodynia over the past 12 months. The patient described the pain as sharp, stabbing and localized to the lower pelvis with radiating to the anorectal area, and also complained of tenesmus. She had a traumatic injury on coccyx 50 years ago and retocele repaired with graft by surgery 15 years ago. At the beginning, she visited other clinics and had been diagnosed with levator ani syndrome. She took a daily dose of 225 mg pregabalin, 650 mg acetaminophen and 75 mg tramadol, and 25 mg sodium tianeptine. She also received superior hypogastric plexus block and caudal epidural blocks. But she was referred to our pain center because the previous therapies had been ineffective. Her pain score on the 10-grade visual analogue score system (VAS, ranging from 0 = no pain to 10 = absolutely intolerable pain) averaged 8/10. Pelvic MRI imaging showed 1.3 cm sized intramural leiomyoma. She was initially treated with caudal epidural block and ganglion impar block, but had the persistent presence of the pelvic pain and coccygodynia. We decided to perform a new technique for inferior hypogastric plexus block with a coccygeal transverse approach to reduce the pelvic pain and coccygodynia. A sufficient explanation was provided to the patient about the procedure and its complications and written consent was received from her. She was positioned prone on the table, with a pillow under the anterior superior iliac spine to flatten the normal lumbar lordosis. The midline of the sacrococcygeal area was cleaned with antiseptic, and sterile drapes were placed. The midline between S2 and S3 junction was the target anatomic landmark for the block (

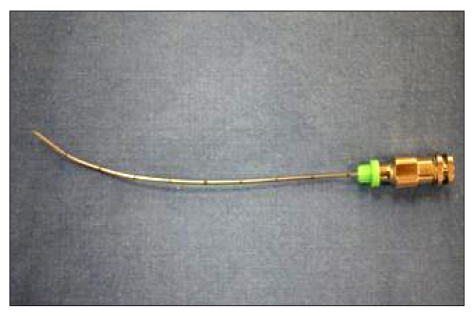

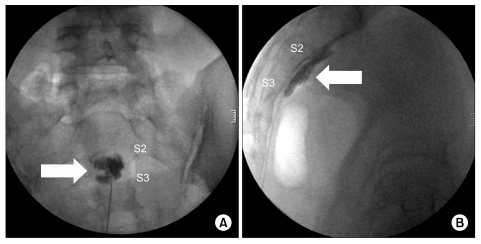

Fig. 1). An optimal sacral foramenal view was obtained as follows. The targeted sacral anatomic landmark was located approximately in the middle of C-arm fluoroscope screen in the anteroposterior view. A 22-gauge, 10-cm block needle was manually bent about 1 cm from its tip to form a 10 degrees angle (

Fig. 2). This bend facilitated needle position toward the anterior aspect of the sacrococcygeal concavity. A skin entry point was just under the transverse process of the coccyx. After the local skin infiltration over the coccyx area, a 22-gause needle was slowly advanced to the inferior of the transverse process of the coccyx. The needle tip was then directed anterior to the coccyx but closed to the anterior surface of the bone until it reached the sacrococcygeal junction. A 22-gauge bent needle was directed superiorly and medially toward the sacrococcygeal junction with the guidance of the sacrum and coccyx. Lateral fluoroscopic imaging was used to identify the sacrococcygeal area, and midline position was confirmed with an AP view. We should pay close attention to needle depth to avoid rectal trauma because this structure lies close to the sacrum. Therefore, we frequently checked lateral and AP fluoroscopic imaging. The needle was advanced to the anterior surface of the sacrum until it reached midline between S2 and S3 junction level. With the needle in the proper position, after a negative aspiration of blood or stool, 1.5 ml of contrast medium was injected to confirm the retroperitoneal location (

Fig. 3). Laterally, the contrast should appear smoothly contoured and hug the sacrococcygeal concavity like a teardrop. There should be a smooth contrast of the dye in the retroperitoneum between the sacrococcygeal region and the bowel gas. Next, for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes, a mixture of 2 ml of 2% lidocaine, 2 ml of 0.25% bupivicaine, and 10 mg of triamcinolone was injected after correct needle position was verified by fluoroscopy. She had significant pain relief with a drop of the VAS level from 8/10 to 2/10 immediately after block. She did not want neurolytic block. Further inferior hypogastric plexus blocks were performed twice in sequence at an interval of 3 months, which diminished VAS to 1/10. The nerve block reduced the amount of supplementary medication needed to control the pain. Pregabalin was reduced from 225 mg to 150 mg per day, and acetaminophen and tramadol was also reduced from 650 mg and 75 mg to 325 mg and 37.5 mg respectively. Her pain improved dramatically immediately after the nerve block (VAS score 2/10). There were no serious procedure-related complications. At present, 6 months following the first treatment, the patient has no problems in performing activities of daily living and works, including sitting and walking. The patient has maintained a VAS of 1-2/10.

| Fig. 1The target anatomic landmark for the block (A) and needle entry point (B). Needle pathway (black allow).

|

| Fig. 2A 22-gause, 10-cm block needle was manually bent about 1 cm from its tip to form a 10 degrees angle.

|

| Fig. 3Inferior hypogastric plexus block after contrast injection. (A) Anteroposterior view, (B) lateral view. Contrast around the interior hypogastric plexus (arrow).

|

Go to :

DISCUSSION

The epidemiology of chronic pelvic pain (CPP) is difficult to ascertain a true prevalence. The annual prevalence of women age 15-73 years old presenting with CPP to primary care in the UK was found to be 38/1,000 comparable to asthma 37/1,000 and back pain 41/1,000 [

3]. CPP is very common in women and is a major public health problem throughout the developed world.

However, diagnosis is often difficult and delayed, leading to frustration and dissatisfaction for both the woman and her doctor [

4]. It is a debilitating disease which often has a major impact on quality of life [

5]. There are often associated negative cognitive, behavioral, sexual and emotional consequences. This clinical condition presumably has a multifactorial etiology and patients with CPP often tend to undergo a multitude of treatments to control symptoms [

6]. However, some patients do not respond to conventional treatments.

Our understanding of the pathophysiology of CPP is still incomplete. It may arise from any structure in or related to the pelvis, including the abdominal and pelvic walls, and not uncommonly the cause of pain is multifactorial [

7]. Therefore, it is a complex pain syndrome that is difficult to diagnose and treat. It is associated with significant economic and social burden [

8].

The anatomy of pelvis visceral innervations is best understood by considering the inferior hypogastric plexus as the center through which most nociceptive information will pass. This plexus supplies branches to the pelvic viscera directly, as well as from subsidiary plexuses (e.g., the superior, middle rectal, bladder, prostate, and uterovaginal plexuses). The sacral sympathetic trunk lies in the parietal pelvic fascia behind the parietal peritoneum and on the ventral surface of the rectum, just medial to its anterior foramina and the existing sacral nerves. Below they converge and unite to form a solitary small ganglion impar which is located anterior to the sacrococcygeal junction. This plexus is located against the inside of the pelvis lateral from the uterovaginal junction and the rectum. It is diffusely spread out and, therefore, difficult to block. From this plexus, most subsidiary plexuses to the pelvic organs will originate. These plexuses include the uterovaginal plexus, vesical plexus, and inferior rectal plexus in the female. In men, the vesical plexus will continue to form the plexus that provides the autonomic innervations of the prostate and vas deferens. Another reason why the inferior hypogastric plexus may not be a good target for neural blockade is that it is predominantly parasympathetic and, therefore, involved in important pelvic reflexes as mentioned earlier [

9].

Although multiple techniques of neurolytic superior hypogastric plexus blockade have been described [

10], there is only one report of neurolytic inferior hypogastric plexus block [

2]. It is a transsacral approach. This block can be performed through S1, S2, S3, or S4 although S2 is usually the preferred access level. Pass an appropriately bent 25-gauge, 3.5-inch spinal needle through the anesthetized track and advance it down to the lateral aspect of the dorsal sacral foramen until contact is made with bone. Advance the needle slowly and incrementally under fluoroscopic guidance through the dorsal sacral foramen toward the medial interior edge of the ventral sacral foramen until contact has been made with the medial bony edge of the ventral sacral foramen. If sacral paresthesia is encountered, retract and rotate the needle slightly to move past the sacral nerve root. Maneuver the needle along the medial edge of the ventral sacral foramen to exit the ventral foramen as medial as possible. Advance the needle antero-medially another millimeter toward the midline pre-sacral plane and inject the contrast medium. When proper needle tip position is assured, inject the active medication, such as 10-15 ml of local anesthetic and steroid combination [

2].

This block has several disadvantages because of transient paresthesia, nerve damage, rectal puncture, vascular penetration, hematoma, and infection. Transient paresthesia is the most common adverse event during transsacral blockade of the inferior hypogastric plexus, occurring in approximately 5% of the procedures performed [

2]. The sacral spinal nerves, with their dorsal and ventral rami, course in close proximity to the advancing needle and may be occasionally contacted by the needle tip.

We performed blockage of the inferior hypogastric plexus using coccygeal transverse approach. This approach consists of needle entry point below the transverse process of the coccyx. After the needle contacts the coccyx, and rotate the bent needle tip slightly to move superiorly and medially toward the sacrococcygeal junction. It is passed close to the anterior surface of the coccyx, until its tip is observed to have reached the midway between S2 and S3 junction level. This technique has fewer disadvantages than transsacral approach such as transient paresthesia, nerve damage, and vascular penetration. But rectal puncture is possible if the needle tip is advanced too deeply into the pre-sacral tissues. This should be easily avoided by visualizing the needle depth using lateral fluoroscopy. We should pay close attention to needle depth to avoid rectal trauma because this structure lies close to the sacrum. Therefore, we frequently checked lateral and AP fluoroscopic imaging. Other possible adverse events include tissue injury, hematoma, and infection. But these complications have not been reported.

Sympathetic nerve block is effective and safe for treatment of pelvic visceral pain, and is a useful adjunct to oral therapy [

10]. Our patient had a pain score reduction of more than 75% after inferior hypogastric plexus block, and the pain relief sustained up to the time of this report, with no early or late complications. This nerve block reduced the amount of supplementary medication needed to control the pain. Although initial results seem promising, follow up durations are relatively short. Since this new coccygeal transverse approach provides easy access to the inferior hypogastric plexus block with a single needle puncture, it may be an alternative to the transsacral approach. Furthermore, larger prospective trials with long-term evaluation are required to determine the ultimate efficacy of this treatment.

In conclusion, the inferior hypogastric plexus block via coccygeal transverse approach is a useful technique for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic pelvic pain conditions involving the lower pelvic viscera.

Go to :