Abstract

Background

Elderly patients visiting pain clinic may be at greater risk of misunderstanding the explanation because of age-related cognitive decline. Video instruction may provide a consistent from of teaching in a visual and realistic manner. We evaluated the effect of educational video on the patient understanding and satisfaction in a group of geriatric patients visiting pain clinic.

Methods

Ninety two patients aged more than 60 years old who were scheduled for transforaminal epidural block were recruited. After exposure to either video or paper instruction process, each patient was asked 5-item comprehension questions, overall satisfaction and preference question. During follow-up period, number of outpatient referral-line call for further explanation was counted.

Results

We observed significantly better comprehension in the video education compared with paper instruction (P < 0.001). Patient satisfaction was also higher in the video group (P = 0.015), and patients visiting pain clinic were more preferred video instruction (P < 0.001). Proportion of referral-line call for further explanation were similar (P = 0.302).

Go to :

In the geriatric population, the prevalence of pain experienced every day for at least 3 to 6 months is estimated up to approximately 30% [1-3]. Older adults may be at greater risk of misunderstanding the explanation because of age-related cognitive decline, which may be further degraded by pain and its treatment of opioids [4]. Patients have a number of expectations of hospital visits including diagnostic information, explanation of their illness and prognosis [5]. For patients visiting pain clinics, thorough explanation of pain is rated as important as the cure of pain [6], and improved patient understanding may lead to greater patient satisfaction and reduced treatment dropout.

The use of educational video offers many favorable characteristics in the variety field of medical area. Video instruction can provide a consistent from of teaching and can communicate certain concepts in a visual and realistic manner [7]. Furthermore, video education has been shown to be superior to traditional method and improve knowledge score [8,9]. However, there are no studies concerning video-assisted education before patient consent specifically focusing on outpatient of pain clinic. The purpose of this study was to evaluate how the implementation of an educational video on the treatment procedure would influence the understanding of procedural process and satisfaction in a group of geriatric patients visiting pain clinic.

Go to :

After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval, the study was conducted in an outpatient pain clinic of Asan Medical Center. Patients aged more than 60 years old who were scheduled for transforaminal epidural block were recruited. The patients with who had impaired cognitive function or had been received medication which could affect the patient's cognition were excluded. Before the physician's explanation for the procedure and attaining consent, patients were randomly allocated to either the paper-based or the video-assisted instruction group using a computer-generated randomization schedule (http://www.randomizer.org/). The randomization sequence was concealed throughout the study from both the study patients and the investigator who was an independent physician from the outpatient pain clinic. Paper group was asked to read a standard text-based patient information leaflet in a separate room. Video group was asked to watch the video with voice-over explanation (Fig. 1). The duration of video was 7 minutes, and the script of video and the text of leaflet mirrored each other so that nearly equivalent amount of factual information was imparted. The patients provided demographic data, including age, employment, education, and marital status.

Immediately after the exposure to video/paper instruction process, each patient was asked 5-item comprehension questions, overall satisfaction and preference question. Comprehension questions asked about essential elements of instruction including treatment purpose, procedure, risk, benefit, and prognosis. Each item used a visual analogue scale scored 0 to 10, to indicate how well they understood the contents of instruction. The visual analogue scale was anchored with 0 ("I don't understand anything about the instruction") and 10 ("I understand everything about the study"). Total possible score for this questionnaire is 0 to 50. Overall satisfaction to the instruction was measured using a 5-point Likert scale (5 = excellent, 4 = good, 3 = fair, 2 = poor, 1 = bad). Preference questions asked about suitability for patients, if respondents wanted the identical version used with other treatment procedure instruction next time. After completion of treatment, number of outpatient referral-line call for further explanation was counted during follow-up period.

All data are presented as mean ± SD or median (inter-quartile range). The normality distribution of the variables was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Patient characteristics were analyzed using Student's t-test. Intergroup differences in non-parametric variables were compared using the Mann-Whitmey U-test. Categorical data were compared using chi-square test or Fisher's exact test as appropriate. Data were analyzed using the SPSS 12.0. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Go to :

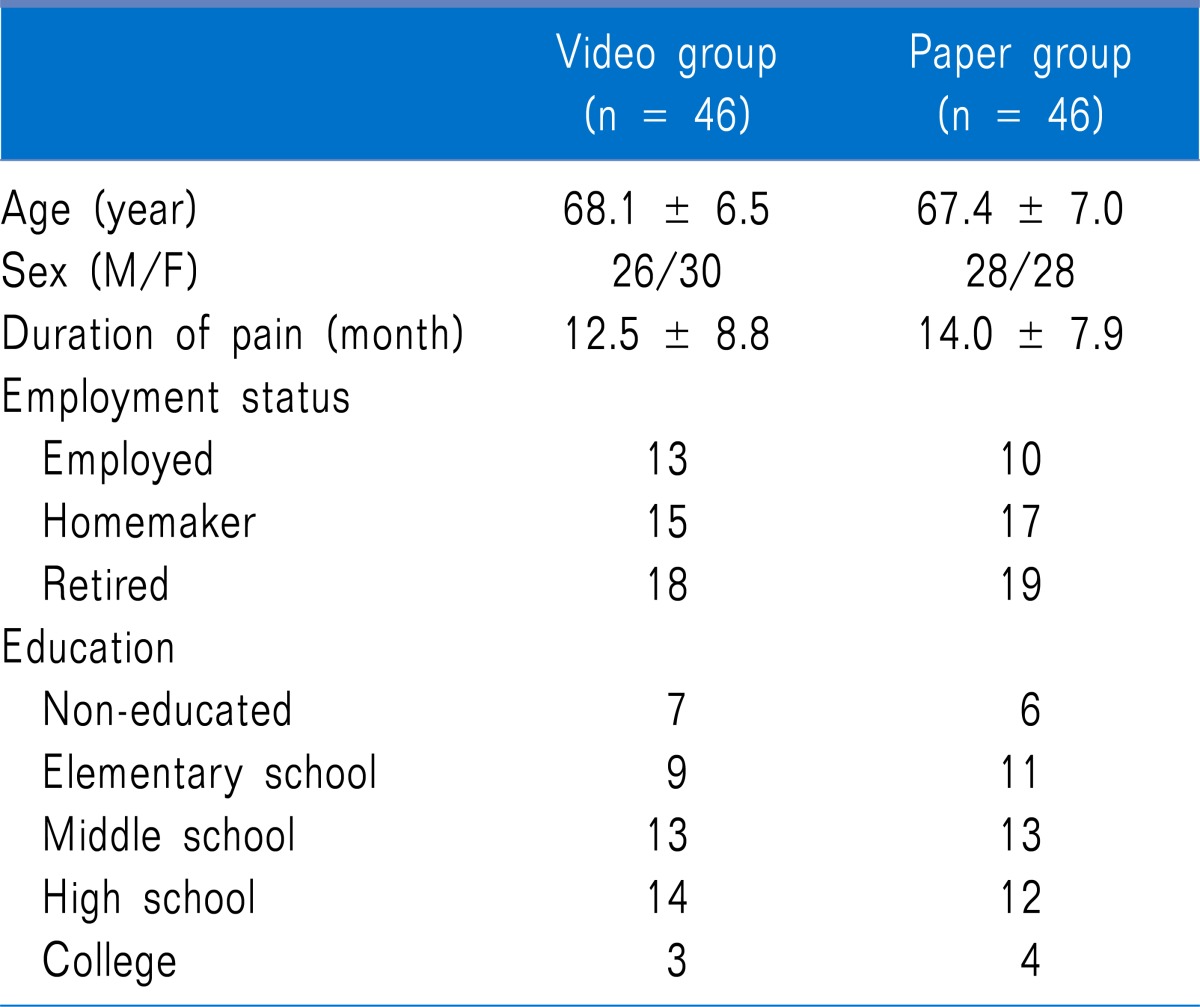

One hundred patients were recruited from outpatient department, and 92 subjects returned the questionnaire (response rate = 92%). Forty-six patients were randomly allocated to watch the video instruction, and 46 patients read the paper leaflet. There was no significant difference in the patient characteristic data between two groups (Table 1).

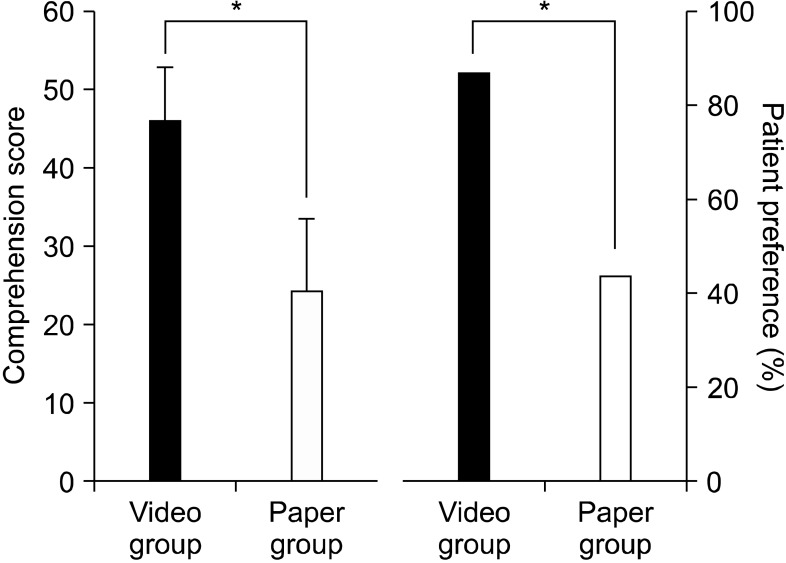

After the education, the comprehension score in video group was significantly higher compared with paper group (43.5 ± 6.5 vs 23.0 ± 8.8; P< 0.001) (Fig. 2). Patient satisfaction score for the instruction was higher in the video group than in the paper group (4.5 ± 0.5 vs 3.2 ± 0.6; P = 0.015). The proportion of patient preference was higher for the video instruction than for the paper version (86.9% vs 43.4%; P< 0.001). Numbers of outpatient referral-line telephone call for further explanation were similar; 6 in the video group and 7 in the paper group (P = 0.302).

Go to :

We observed significantly better comprehension of treatment details in elderly patients exposed to the video education compared with paper-based instruction. Patient satisfaction was also higher in the video group, and patients visiting pain clinic were more preferred video instruction.

Although printed materials are commonly used to convey information, they are often produced at reading level above that of intended reader. For elderly patients with low reading skills or those with visual impairments, video instruction may offer significant advantages over written material because of their visual appeal. Recently, video have become an increasingly common modality for providing patients with information about the disease and its treatment. Adopting such approach for the permission and assent process has potential to improve comprehension and patient satisfaction with the process. Results of present study correspond with the results of previous studies which reported that video instruction provides better comprehension compared with paper based traditional method in various medical field of healthcare [10,11].

Patient satisfaction is one of the most studied issues of health care. It can be a valid indicator of quality of care, and measurements of patients satisfaction has been shown to be important determinant of overall patient outcomes during hospital visit [12]. In our results, patient satisfaction in the video group was higher than in the paper group, and the elderly patients were more preferred the video instruction. Contents can be presented in a variety of ways. It is inferred that although almost equivalent amount of factual information was imparted in both modality, more realistic nature of video instruction promotes patient understanding, resulting video as more preferred education styles.

There is general consensus that video consistently increase short-term knowledge among patients of disparate interests. Stalonas et al. [13] showed that video instruction is more effective in increasing short-term knowledge than did live lecture or written material for instructing alcoholic patients. However, knowledge of alcoholism returned to baseline at 1 month later, which suggests that video education is no better than other methods in enhancing long-term knowledge retaining. Importantly, despite of initial high comprehension rate of video instruction, we observed similar numbers of outpatient referral-line telephone call for further explanation. Therefore, the patient education with whatever modality must be repeated to maintain an initial beneficial effect.

Our study may be criticized for not calculating cost differences between the two modalities. Budgetary cost for novel approach might be higher because of expertise and equipment needed. However, the improvement in patients understanding and increase in quality may justify these costs. On the other hands, centralized production of such materials may be a cost savings for society-based multi-site projects. Centralized production can be controlled for clinical details and standardized information, thus improving accuracy and quality [14]. In addition, improvement of paper-type instruction such as adding the intuitive image and more detailed explanation would facilitate patient comprehension and reduce the bias between physicians.

In conclusion, our results suggest that a video approach to instruction process before consent improves treatment comprehension in geriatric patient visiting pain clinic. Although its effect in long-term knowledge is less clear, we hope that increase of comprehension in patients visiting pain clinic will encourage them to more compliable to their treatment. Furthermore, there is limited time for sufficient education in most healthcare providers, thus video-assisted education might be valuable ancillary tool in pain clinic.

Go to :

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Jina Kim (Department of Nursing, Asan Medical Center) for making video for patient instruction.

Go to :

References

1. Park EJ, Han KR, Kim DW, Kim C. A clinical survey of the patients in neuro-pain clinic at Ajou University. Korean J Pain. 2007; 20:181–185.

2. Jo DH, Hong JH, Kim MH. A survey on clinical characteristics of patients visiting pain clinics. Korean J Pain. 2005; 18:146–150.

3. Blyth FM, March LM, Brnabic AJ, Jorm LR, Williamson M, Cousins MJ. Chronic pain in Australia: a prevalence study. Pain. 2001; 89:127–134. PMID: 11166468.

4. Karp JF, Reynolds CF 3rd, Butters MA, Dew MA, Mazumdar S, Begley AE, et al. The relationship between pain and mental flexibility in older adult pain clinic patients. Pain Med. 2006; 7:444–452. PMID: 17014605.

5. Jackson JL, Kroenke K. The effect of unmet expectations among adults presenting with physical symptoms. Ann Intern Med. 2001; 134:889–897. PMID: 11346325.

6. Petrie KJ, Frampton T, Large RG, Moss-Morris R, Johnson M, Meechan G. What do patients expect from their first visit to a pain clinic? Clin J Pain. 2005; 21:297–301. PMID: 15951646.

7. Meade CD. Producing videotapes for cancer education: methods and examples. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1996; 23:837–846. PMID: 8792353.

8. Gagliano ME. A literature review on the efficacy of video in patient education. J Med Educ. 1988; 63:785–792. PMID: 3050102.

9. Phelan EA, Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Weinstein JN, Ciol MA, Kreuter W, et al. Helping patients decide about back surgery: a randomized trial of an interactive video program. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001; 26:206–211. PMID: 11154542.

10. Eaden J, Abrams K, Shears J, Mayberry J. Randomized controlled trial comparing the efficacy of a video and information leaflet versus information leaflet alone on patient knowledge about surveillance and cancer risk in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2002; 8:407–412. PMID: 12454616.

11. Oermann MH, Webb SA, Ashare JA. Outcomes of videotape instruction in clinic waiting area. Orthop Nurs. 2003; 22:102–105. PMID: 12703393.

12. Abramowitz S, Coté AA, Berry E. Analyzing patient satisfaction: a multianalytic approach. QRB Qual Rev Bull. 1987; 13:122–130. PMID: 3108744.

13. Stalonas PM, Keane TM, Foy DW. Alcohol education for inpatient alcoholics: a comparison of live, videotape and written presentation modalities. Addict Behav. 1979; 4:223–229. PMID: 495245.

14. Flory J, Emanuel E. Interventions to improve research participants' understanding in informed consent for research: a systematic review. JAMA. 2004; 292:1593–1601. PMID: 15467062.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download