Abstract

Background

Prevalence of chronic pain and its association with demographic characteristics have been reported by different studies from different geographical regions in the world. However, data from many Middle East countries including Iran (especially southern Iran) are scare. The aim of the present study was to demonstrate the prevalence of chronic pain and its association with demographic, psychological and socioeconomic factors in an Iranian population.

Methods

In this population-based survey, the target population was comprised of subjects aged 20 to 85 years residing in Jahrom, southern Iran during 2009-2011. All eligible subjects were invited to participate in the study. Before a detailed questionnaire was given; face to face interviews were done for each individual.

Results

There were 719 men and 874 women with an average age of 40.5 years at the onset of the study. Among the study population, 38.9% (620/1,593) complained of chronic pain, of whom 40.8% (253/620) were men and 59.2% (367/620) were women. Foot and joint pain were observed in 31.9%. Hip and spine pain, migraine and tension headaches, heart pain, and abdomen pain were observed in 21.5%, 15.5%, 9.5%, and 8.0% of chronic pain cases, respectively. There was a significant association among the covariables age, sex, overweight, educational level, income, and type of employment with chronic pain as the dependent variable (P < 0.0001).

Go to :

Chronic pain is a prolonged pain which typically lasts for at least three months [1,2]. This type of pain is common all over the world and different studies have demonstrated that approximately 3.9% to 48% of the general population suffer from various types of chronic pain [3-11]. Chronic pain may be caused or exasperated by range of environmental and individual factors [12]. A number of studies propose a connection between chronic pain and demographic factors, such as age, sex, and educational level [13-18]. Most chronic pain, such as back pain, joint pain and accelerated headaches, are very common [19].

Chronic pain often affects an individual's outlook on life [20]. In such patients, quality of life and their immediate family and friends are significantly affected [21]. In some cases, this pain is associated with unsuccessful treatment and a variety of complications such as sleep disorders, loss of appetite, chronic fatigue, drug-dependency, stress and fear from the cause of the pain, hopelessness, and depression [14,19,22,23].

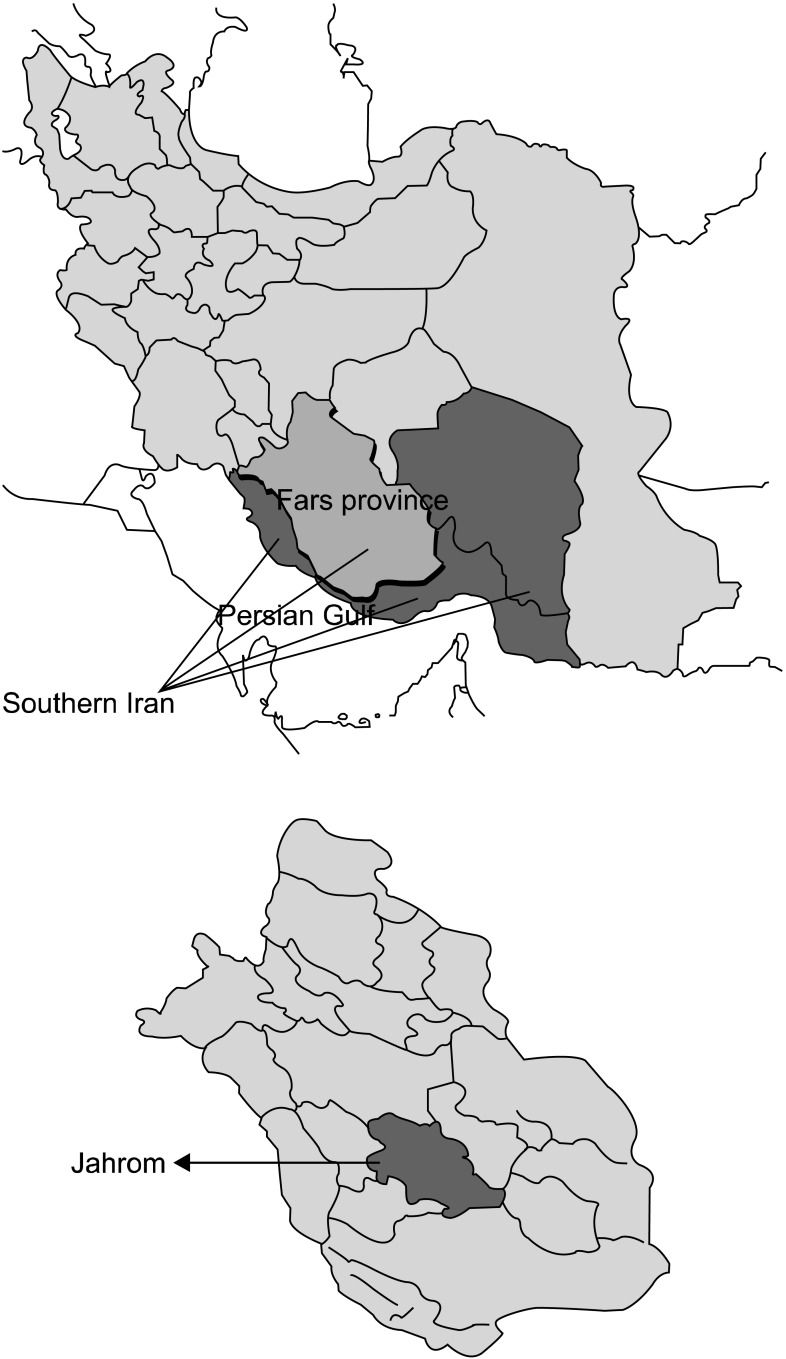

Southern Iran is a vast region that is located in the southern part of Zagros and in the northern part of the Persian Gulf. This area includes different provinces with the Fars province being the biggest one. Jahrom is a city which is located in the southern part of Fars (Fig. 1). Its population was 211,331 in the 2010 census.

There are major clinical centers in Jahrom that are the most tertiary referral centers from among all parts of southern Fars, Iran. The patients from all parts of southern Fars are referred to these centers to assess the progression of disease and getting the appropriate medication.

There is an agreement among academics concerning the importance of epidemiological investigations on chronic pain, particularly those that examine the social and economic contexts of patients' lives. Nevertheless, there are few publications on chronic pain in the international literature in Iran. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that demonstrated the prevalence of chronic pain and its association with demographic, psychological and socioeconomic factors in an Iranian population.

Go to :

The target population among the Iranian general population was based on a descriptive cross-sectional survey consisting of women and men aged 20 to 85 years residing in Jahrom, Iran between the spring of 2009 and the fall of 2011. The sample size was calculated using 95% confidence intervals, with 2% precision and a prevalence of 20%. A sample size of about 1,300 individuals was suitable for the present study. Because of the difficulty in household examination that people might be rejected our invitation to participate in the study by the purpose of interference in their private life, the sample size (1,300 individuals) was increased by 30% to compensate for any refusals, and finally 1,690 participants were invited to participate in the present study. The study employed a two-stage stratified cluster technique. At the first stage, the city (Jahrom) was divided into seven regions. Separate strata were formed based on the population covered by each outpatient clinic. Then, independent clusters were drawn from each stratum. At the second stage, families lists were prepared for each cluster and families were chosen from those lists. Generally, one person from each family was randomly selected. The eligible participants had to fulfill the inclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age between 20 and 85 years; (2) chronic pain in the previous six months; and (3) provide written informed consent before enrollment.

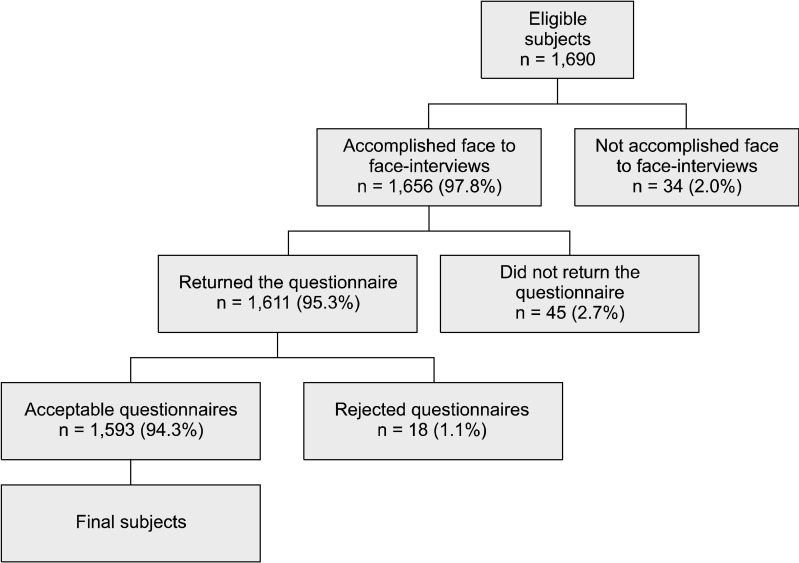

The final sample population of the survey consisted of 1,690 subjects aged 20 to 85 years. Of them, 34 dropped out of the study before interview; therefore, 1,656 (98.0%) participants were interviewed and 1,611 of them (95.3%) returned their questionnaires (Fig. 2). The overall response rate was 94.3% with 1,593 participants.

The present study complied with all of the principles of research ethics regulations adopted by the Iranian Ministry of Health. The legal guardians of the residents provided written informed consent, which was registered before participation in the study.

All of the subjects were investigated with a structured protocol that included a face to face-interview by a trained staff member and used a standardized questionnaire which had a good reliability and validity. We conducted a pilot study on over 200 individuals to assess the reliability and validity of the questionnaire. The reliability of the questionnaire was confirmed using the test-retest method (r = 0.71) which showed good reliability. Five physiologists and 5 public health experts evaluated the contents of the questionnaire, and as a result, the contents were determined as having good validity.

The first part of the questionnaire included demographic characteristics such as age, sex, weight, height, literacy level, employment type, and income. Chronic pain symptoms were first asked with a yes or no question "Have you felt any pain during the past 6 months?" If the answer was yes, "how often" was asked with the following choices given, "once a week, several times a week or constantly." Additionally, they were asked to define "which of the nine following anatomical regions are affected by chronic pain: head and face, chest and shoulder, hand, heart, abdomen, hip and spine, genitalia, and foot and joints?" Individuals were asked about their medical histories which included any injuries or surgeries, or specifically any surgeries for cancer.

In addition to chronic pain, the questionnaire also included separate questions on the following problems with pain: hypo or hypertension, tachycardia, dehydration, tachypnea, and agitation. The impact of chronic pain on social and ethical behaviors (disruption in work, driving, school attendance, sexual behavior, domestic chores, sleep disorders, depression, aggressive behavior, irritation, and stress subsequent to their pain) was assessed.

In order to improve the methods, a pilot study was carried out 4 months before the field work started. We provided detailed written instructions before the study for the assessment of pain status. All staff members attended a 1-week training course.

The information on demographic, psychological and socioeconomic factors was obtained by questionnaires. The subjects were classified as 1) uneducated, if they did not have any academic degrees; 2) primary school, if they had finished their education with a primary degree; 3) junior high school, if they had finished their education with an elementary degree; 4) senior high school; 5) associate degree; 6) license; and 7) master's degree or higher. The type of employment was considered by a single question and classified into one of the following subgroups: employed (official employee, private employee, and guilds), and unemployed in any official agencies (shopper, businesspeople, farmer and laborer). The participants' height and weight were asked in the questionnaire and measured by trained staff. Body mass index (BMI) was classified as follows: 1) BMI < 25; and 2) BMI ≥ 25. Severe pain that required referral to a physician or medication was considered as pain while transient pain was not considered.

Results were reported as the means ± standard deviation (SD) or median for quantitative variables and percentages for categorical variables. The groups were compared using the Student's t-test and the chi-square test (or Fisher's exact test if required) for categorical variables. P values of 0.05 or less were considered to be statistically significant. All the statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) for Windows. A logistic regression model was applied to define which demographic variables (sex, age, BMI, education level, family income and job type) and other variables (medical history which included injuries and surgeries, and specifically any surgeries for cancer) had significant effects on chronic pain.

Go to :

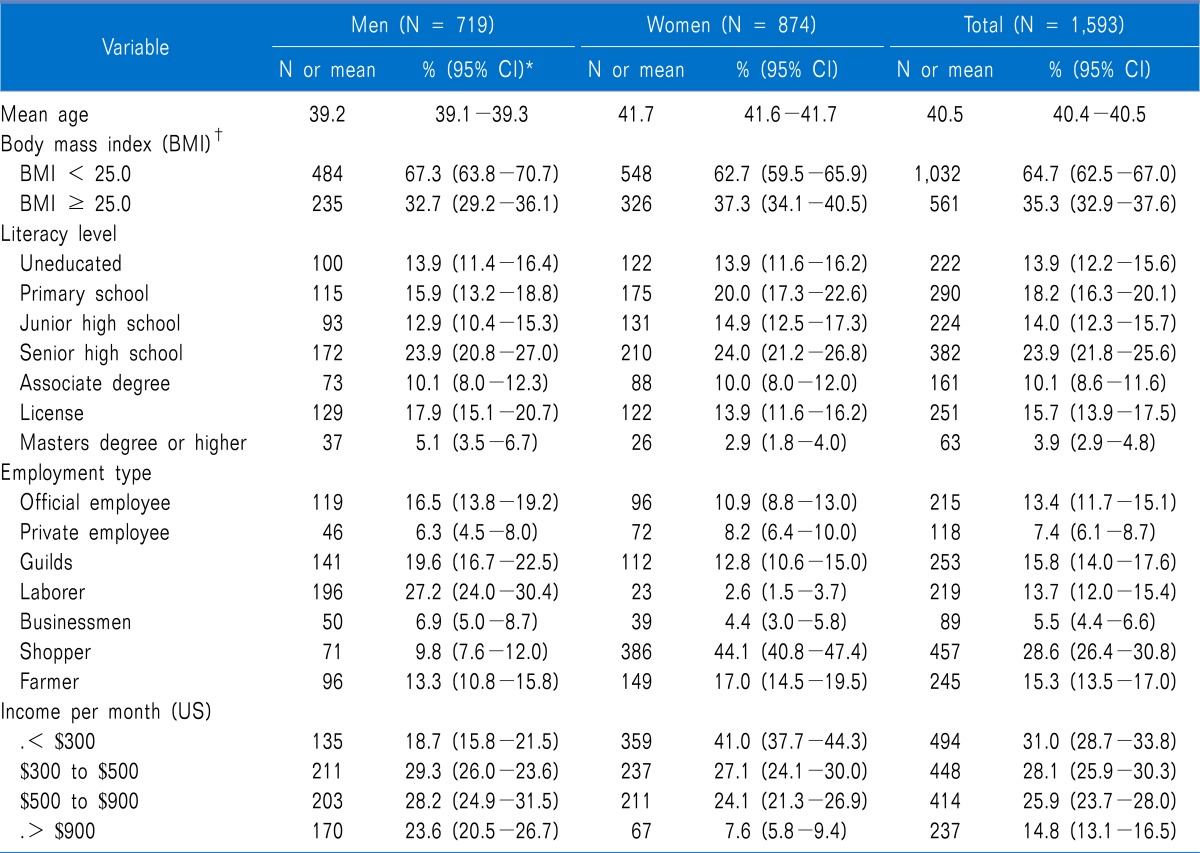

The present study included 1,593 individuals of whom 719 (45.1%) were men and 876 (59.4%) were women. The average age of the participants was 40.45 years ranging from 20 to 85 years. The median age of the participants was 38 years. The proportion of participants who had a BMI < 25 was 64.7% (1,032/1,593). About 23.9% (382/1,593) never received a senior high school education. Among the participants 13.7% (219/1,593) were laborers. About 28.1% (448/1,593) had a monthly income of US $300 to $500. The detailed demographic characteristics of the study group are presented in Table 1.

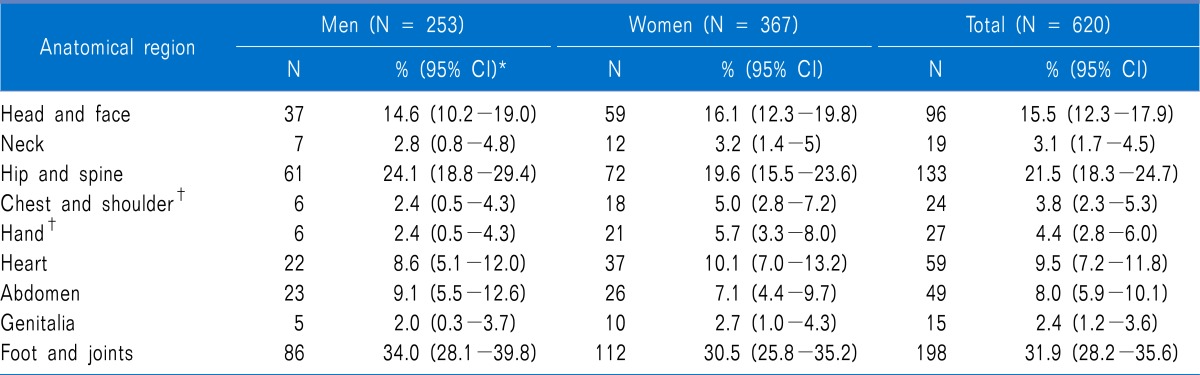

Among the study population 38.9% (620/1,593) complained of chronic pain, of whom 40.8% (253/620) were men and 59.2% (367/620) were women. 18.1% (288/1,593) of the participants suffered from chronic pain several times a week. Foot and joint pain were the most common types of chronic pain (31.9%), followed by hip and spine pain (21.5%) and migraine and tension headaches (15.5%; Table 2). 36.1% (224/620) of the chronic pain patients had depression because of the pain. Among the patients, 34.2%, 29.2%, 31.2%, 32.3, 26.7%, and 35.1% suffered from hypotension, hypertension, tachycardia, dehydration, tachypnea, and agitation, respectively. Other associated problems such as nausea, vomiting and loss of appetite were found in 7.9%, 7.6%, and 6.7% of the population, respectively. There was a disruption in work, driving, school attendance, sexual behavior, and domestic chores due to pain in 71.2%, 42.4%, 34.5%, 33.8%, and 33.5% patients, respectively. Meanwhile, 17.9% of the patients had sleep disorders from the pain, and 12.6%, 7.1%, 5.3% and 3.2% demonstrated aggressive behavior, irritation, and stress subsequent to their pain, respectively.

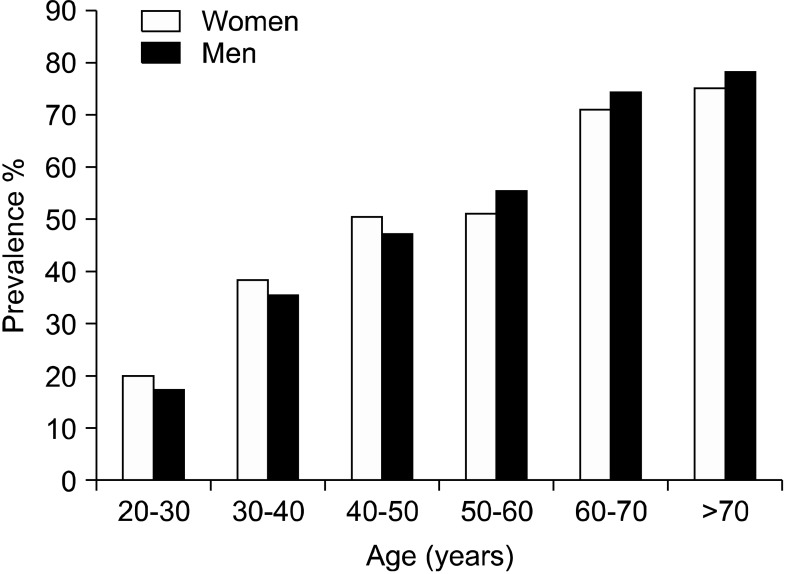

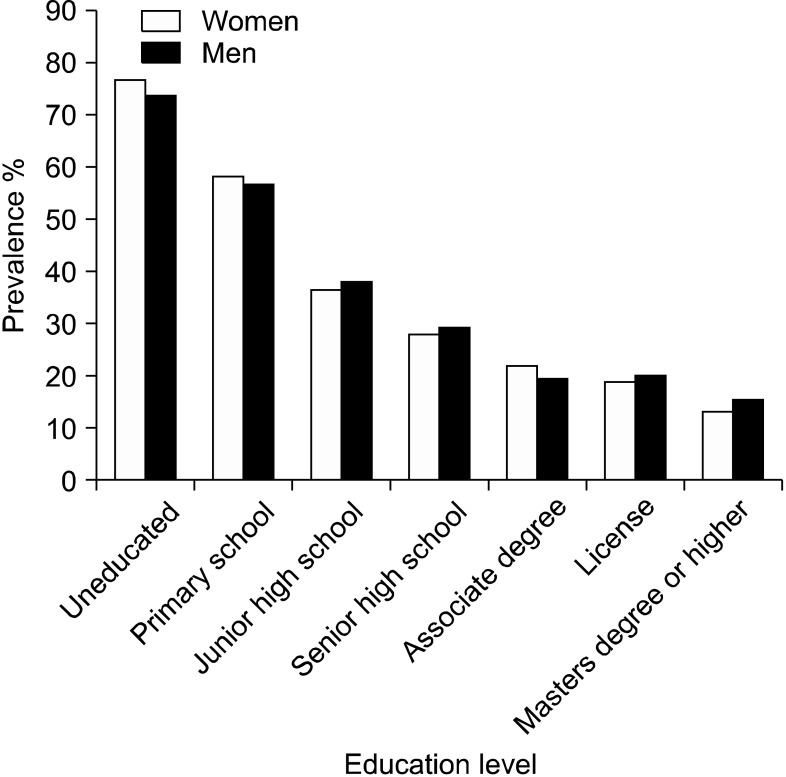

Chronic pain was more prevalent in individuals 70 to 80 years of age (76.2%) and was less common in participants 20 to 30 years of age (Fig. 3). An increase in the education level was associated with a decrease in the pain ratio (Fig. 4).

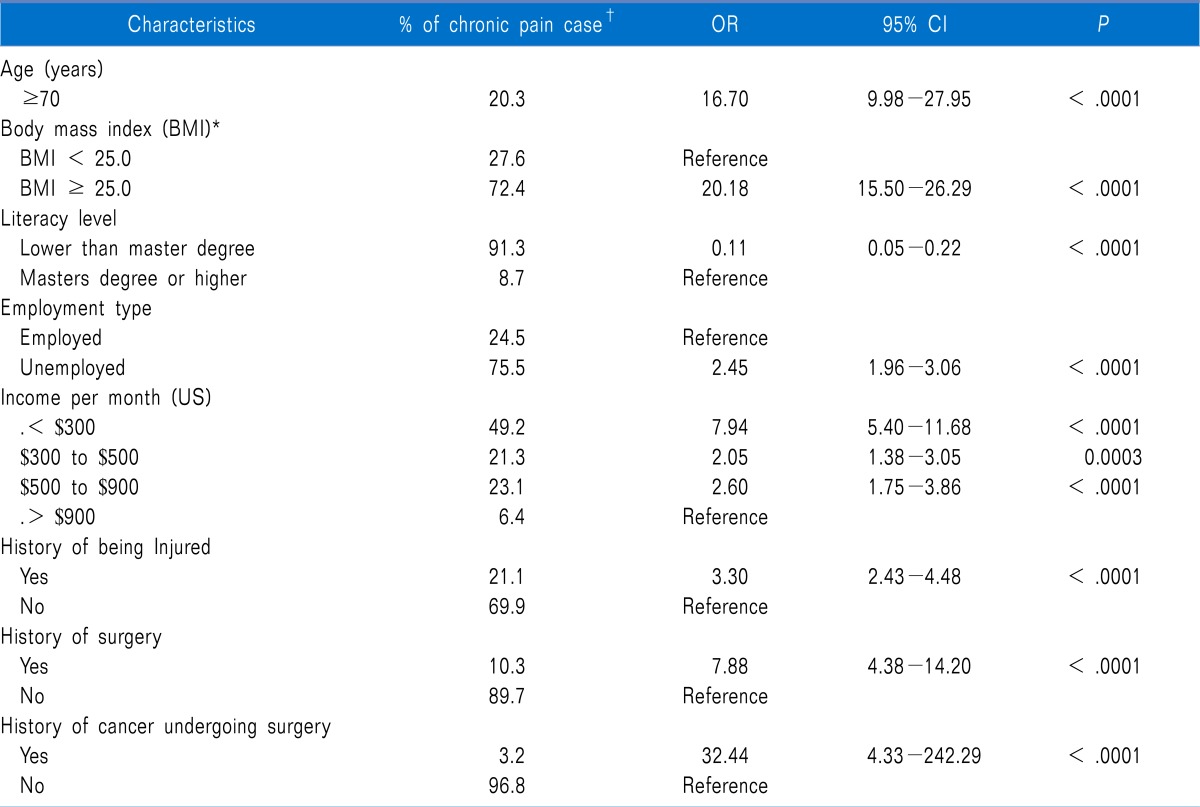

Logistic regression analysis showed the significant factors that are associated with chronic pain including age, type of employment, education, BMI (overweight and obese), monthly income, and a medical history of injuries, surgeries, and cancer surgeries. A significant relationship was found between age and chronic pain (P < .0001, OR = 16.70; CI = 9.98-27.95). Results showed that there was a statistically significant relationship between chronic pain and education level (OR = 0.11, CI = 0.05-0.22; P < .0001). A significant association between employment type and the prevalence of chronic pain was confirmed (OR = 2.45, CI = 1.96-3.06; P < .0001). The results of the logistic regression analysis for all variables are presented in Table 3. Among the population, 21 patients underwent surgery for cancer and their pain lasted longer and was more severe.

Go to :

To our knowledge, this is the first study on the prevalence and determinants of chronic pain in Iranians residing in southern Iran. The first advantage of this study is the large sampling of individuals that were selected from the general population rather than from a special clinical setting. The second advantage of this study is that it assessed the prevalence of chronic pain and its association with demographic, psychological and socioeconomic factors simultaneously. To the best of our knowledge, there are no distinctive population-based studies on individuals with chronic pain in southern Iran that assess the prevalence and determinants of chronic pain.

This study showed that the prevalence of chronic pain among the population in the present study was 38.9% and that it was significantly higher in women compared to men. In 2004, a study from Canada by Meana et al. [24] also confirmed a greater prevalence of pain among females. Various causes have been proposed to explain the increased prevalence of chronic pain among women. Some studies have proposed that female sex hormones are a primary cause that can affect the sense of pain [25]. Furthermore, some diseases, such as osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, migraine and fibromyalgia, are more common among women. The prevalence of chronic pain is the same in both genders after 70 years of age [3,25].

Our results showed that the prevalence of chronic pain increased with age. It was more common in persons 70 to 80 years of age and was less common in persons 20 to 30 years of age. Results of other previous studies reported that the prevalence of pain varied individually with increased age. Helme and Gibson [12] found that the prevalence of pain increased with older age. Some studies showed that people aged 60 to 65 have a greater tolerance for pain [24,26]. The other theory is that some visceral pains, such as abdominal and ischemic heart pain, are sensed less in older aged people [3].

In the present study, a significant association was found between chronic pain and income: chronic pain was more prevalent among low-income individuals. Those with adequate income benefitted from different types of social insurance. There are two types of health insurance in Iran. For routine insurance, the cost is supported by the employer while for supplementary insurance, the patient pays; thus, those with adequate income are able to afford supplementary insurance and benefit from its advantages, obtain better medical and medicine support, complete their treatment period and experience less pain. Those without adequate income have no access to tertiary treatment centers, and perhaps their conditions are not diagnosed properly and consequently suffer from chronic pain [27,28].

Our results showed a significant relationship between chronic pain and education level. Chronic pain was less prevalent among those with a Master's degree or higher. Individuals with higher education levels, who generally have sufficient knowledge on disease and subsequent complications, devote more attention to their health and treat their disease in an appropriate timely manner and are healthier. In contrast, those with a low education level devote less attention to their hygiene and health, and do not have enough information on disease and consequently, suffer from chronic disease with a poor outcome. There is a direct association between education level and some diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, musculoskeletal diseases, neoplasm, and psychiatric, pulmonary and renal diseases [29].

The prevalence of chronic pain differs across various types of employment. Chronic pain was more common among unemployed (especially, shoppers) and less common among employees (especially, official employee as in a civil servant). The most prevalent industries in southern Iran are agriculture, gardening and looming, which are physically demanding and lead to musculoskeletal, joint and shoulder pain. Most of the official employees as in both civil servant and those pay taxes and benefits also work overtime, which results in some conditions such as shoulder and neck pain. On the other hand, a considerable number of shoppers had small shops with low income, and their lower economic status can lead to psychological stress and various diseases and subsequent pain. These results are consistent with those reported in previous studies [12,24,30].

Our study confirmed that the type of disease affects the prevalence and severity of chronic pain. For example, knee and back pain and headache had more negative effects on the daily functions of the patients. Patients who were overweight and obese were more disposed to chronic pain than the other patients. Patients who had undergone surgery still complained of pain, which was more severe in those who had undergone surgery for cancer, possibly due to the psychological effects of the cancer. Studies in other countries also reported a considerable prevalence for headache and chronic back, knee, pelvic and shoulder pain [15,18,22,31].

Consistent with previous studies, our results confirm the negative impact of chronic pain on the social lives of patients leading to changes in lifestyle. Patients pay a lot for the treatment of chronic pain resulting in a considerable prevalence for depression and sleep disorder, and the same is true for the treatments among our study population [32].

Chronic pain is an important and common public health problem in Iran. Demographic, psychological and socioeconomic factors affect the prevalence of chronic pain. We recommend establishing consultant centers or outpatient pain clinics to train general physicians and other staff members in the prevention chronic pain and for the psychological support of chronic pain patients to reduce their pain.

Go to :

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge the authorities of Jahrom University of Medical Sciences for financial support.

Go to :

References

1. Cho SK, Heiby EM, McCracken LM, Moon DE, Lee JH. Daily functioning in chronic pain: study of structural relations with posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, pain intensity, and pain avoidance. Korean J Pain. 2011; 24:13–21. PMID: 21390174.

2. van Dijk A, McGrath PA, Pickett W, VanDenKerkhof EG. Pain prevalence in nine- to 13-year-old schoolchildren. Pain Res Manag. 2006; 11:234–240. PMID: 17149456.

4. Sjøgren P, Ekholm O, Peuckmann V, Grønbaek M. Epidemiology of chronic pain in Denmark: an update. Eur J Pain. 2009; 13:287–292. PMID: 18547844.

5. Johannes CB, Le TK, Zhou X, Johnston JA, Dworkin RH. The prevalence of chronic pain in United States adults: results of an Internet-based survey. J Pain. 2010; 11:1230–1239. PMID: 20797916.

6. Mohseni-Bandpei MA, Fakhri M, Ahmad-Shirvani M, Bagheri-Nessami M, Khalilian AR, Shayesteh-Azar M, et al. Low back pain in 1,100 Iranian pregnant women: prevalence and risk factors. Spine J. 2009; 9:795–801. PMID: 19574106.

7. Leighton DJ, Reilly T. Epidemiological aspects of back pain: the incidence and prevalence of back pain in nurses compared to the general population. Occup Med (Lond). 1995; 45:263–267. PMID: 7579302.

8. Palmer KT, Walsh K, Bendall H, Cooper C, Coggon D. Back pain in Britain: comparison of two prevalence surveys at an interval of 10 years. BMJ. 2000; 320:1577–1578. PMID: 10845966.

9. Blyth FM, March LM, Brnabic AJ, Jorm LR, Williamson M, Cousins MJ. Chronic pain in Australia: a prevalence study. Pain. 2001; 89:127–134. PMID: 11166468.

10. Hanna M. Pain in Europe: a public health priority. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2012; 26:182–184.

11. Yeo SN, Tay KH. Pain prevalence in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2009; 38:937–942. PMID: 19956814.

12. Helme RD, Gibson SJ. The epidemiology of pain in elderly people. Clin Geriatr Med. 2001; 17:417–431. PMID: 11459713.

13. Stronks K, van de Mheen H, van den Bos J, Mackenbach JP. The interrelationship between income, health and employment status. Int J Epidemiol. 1997; 26:592–600. PMID: 9222785.

14. Mäntyselkä PT, Turunen JH, Ahonen RS, Kumpusalo EA. Chronic pain and poor self-rated health. JAMA. 2003; 290:2435–2442. PMID: 14612480.

15. Green CR, Ndao-Brumblay SK, Nagrant AM, Baker TA, Rothman E. Race, age, and gender influences among clusters of African American and white patients with chronic pain. J Pain. 2004; 5:171–182. PMID: 15106130.

16. Saastamoinen P, Leino-Arjas P, Laaksonen M, Lahelma E. Socio-economic differences in the prevalence of acute, chronic and disabling chronic pain among ageing employees. Pain. 2005; 114:364–371. PMID: 15777862.

17. Poleshuck EL, Green CR. Socioeconomic disadvantage and pain. Pain. 2008; 136:235–238. PMID: 18440703.

18. Hagen K, Zwart JA, Svebak S, Bovim G, Jacob Stovner L. Low socioeconomic status is associated with chronic musculoskeletal complaints among 46,901 adults in Norway. Scand J Public Health. 2005; 33:268–275. PMID: 16087489.

19. Loisel P, Durand P, Abenhaim L, Gosselin L, Simard R, Turcotte J, et al. Management of occupational back pain: the Sherbrooke model. Results of a pilot and feasibility study. Occup Environ Med. 1994; 51:597–602. PMID: 7951791.

20. Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain. 2006; 10:287–333. PMID: 16095934.

21. Gustorff B, Dorner T, Likar R, Grisold W, Lawrence K, Schwarz F, et al. Prevalence of self-reported neuropathic pain and impact on quality of life: a prospective representative survey. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2008; 52:132–136. PMID: 17976220.

22. Park HJ, Moon DE. Pharmacologic management of chronic pain. Korean J Pain. 2010; 23:99–108. PMID: 20556211.

23. Oladeji BD, Makanjuola VA, Esan OB, Gureje O. Chronic pain conditions and depression in the Ibadan Study of Ageing. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011; 1–7. PMID: 21241528.

24. Meana M, Cho R, DesMeules M. Chronic pain: the extra burden on Canadian women. BMC Womens Health. 2004; 4(Suppl 1):S17. PMID: 15345080.

25. Maruta T, Osborne D. Sexual activity in chronic pain patients. Psychosomatics. 1978; 19:531–537. PMID: 704780.

26. Dunn KS. Testing a middle-range theoretical model of adaptation to chronic pain. Nurs Sci Q. 2005; 18:146–156. PMID: 15802747.

27. Katz JN. Lumbar disc disorders and low-back pain: socio-economic factors and consequences. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006; 88(Suppl 2):21–24. PMID: 16595438.

28. Deyo RA, Tsui-Wu YJ. Functional disability due to back pain. A population-based study indicating the importance of socioeconomic factors. Arthritis Rheum. 1987; 30:1247–1253. PMID: 2961343.

29. Pincus T, Callahan LF, Burkhauser RV. Most chronic diseases are reported more frequently by individuals with fewer than 12 years of formal education in the age 18-64 United States population. J Chronic Dis. 1987; 40:865–874. PMID: 3597688.

30. Lohmander LS, Ostenberg A, Englund M, Roos H. High prevalence of knee osteoarthritis, pain, and functional limitations in female soccer players twelve years after anterior cruciate ligament injury. Arthritis Rheum. 2004; 50:3145–3152. PMID: 15476248.

31. Ghaffari M, Alipour A, Jensen I, Farshad AA, Vingard E. Low back pain among Iranian industrial workers. Occup Med (Lond). 2006; 56:455–460. PMID: 16837536.

32. Asghari A, Ghaderi N, Ashory A. The prevalence of pain among residents of nursing homes and the impact of pain on their mood and quality of life. Arch Iran Med. 2006; 9:368–373. PMID: 17061612.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download