This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Despite recent methodological advancement of the practical pain medicine, many cases of the chronic anorectal pain have been intractable. A 54-year-old female patient who had a month history of a constant severe anorectal pain was referred to our clinic for further management. No organic or functional pathology was found. In spite of several modalities of management, such as medications and nerve blocks had been applied, the efficacy of such treatments was not long-lasting. Eventually, she underwent temporary then subsequent permanent sacral nerve stimulation. Her sequential numerical rating scale for pain and pain disability index were markedly improved. We report a successful management of the chronic intractable anorectal pain via permanent sacral nerve stimulation. But further controlled studies may be needed.

Go to :

Keywords: anorectal pain, sacral nerve stimulation

In practical aspects, there have been many cases of intractable perianal or anorectal pain. Various pathological conditions, such as gynecourological and coloproctologic problems, can cause the anorectal pain, but there are conditions of functional anorectal pain (FAP) syndrome [

1] which come from unknown origin.

Various therapeutic modalities for FAP including medications, electrophysical maneuvers (electrgalvanic stimulation, levator massage and sitz baths etc.) and surgical approaches have been frustrating. Since Plancarte and coworkers [

2], some authors have been reported for significant efficacy of superior hypogastric plexus blockade or ganglion impar block for pelvic and anorectal pain [

3].

Since its first application in 1967, spinal cord stimulation (SCS) has been known as a well-established method of managing a variety of chronic and intractable pain. However, several technical factors significantly limit its application to the treatment of pelvic pain [

4]. In 1988, Tanagho and Schmidt [

5] reported the first literature of implantation of sacral nerve stimulator for the treatment of functional urologic disorders. After that time, the effectiveness of sacral nerve stimulation (SNS) through the sacral foramen for the treatment of pain in patients with interstitial cystitis was reported. Some authors then proposed this treatment for chronic idiopathic anal pain [

6]. Recently, some cases reported good results of SNS in patients with anorectal pain using the method of transsacral foraminal approach [

7,

8]. This method has been associated with technical failures in maintaining electrode position and consistent outcomes [

9]. To overcome these limitations, a percutaneous retrograde (cephalocaudal or toward the sacrum) approach for SNS had been introduced [

4]. We reported our experience of a successful management of the chronic intractable anorectal pain via retrograde percutaneous SNS.

CASE REPORT

A 54-year-old female patient was referred to our clinic who had a month history of a severe anorectal pain. In past history, she had been treated for depression and hypothyroidism at other clinic, and otherwise unremarkable. She received urogynecologic and coloproctologic evaluations and there was no any abnormal finding. Her numerical rating scale (NRS) score for pain (0 means no pain, 10 means the worst pain imaginable) was 8-9. Pain was a grabbing nature and lasting for nearly all day long. And it was irrelevant with defecation, micturition and sexual intercourse. The bowel habit was of normal frequency and consistency. There was no evacuatory difficulty. Her sitting tolerance was within 3 minutes. On physical examination including digital rectal examination, we couldn't find any other abnormal finding. She was checked mild disc protrusion at L4-5 and L5-S1 disc levels and otherwise unremarkable on radiologic evaluations including pelvic and lumbar magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies. No abnormal findings were noted on laboratory evaluations. Initial caudal block with steroid was invalid. And then, we conducted a consecutive nerve blocks such as selective transforaminal epidural block at suggested problematic lumbar levels, superior hypogastric block and ganglion impar block under fluoroscopic guidance. Despite of these interventions, her pain was not improved. Furthermore she attempted incidental suicide due to unrelenting pain. Eventually, we scheduled for SNS 12 months after initial visit of our pain clinic. At that time, her medications included tramadol 300 mg, nortriptylline 100 mg, pregabalin 600 mg, morphine sustained release 60 mg, fentanyl patch 25 µg/h and additional rescue dose of hydromorphone 4 mg per day. With fully informed consent, she underwent one-week scheduled trial of SNS. In prone position, after draping by sterile methods, two 15-gauge Tuohy needles were inserted into the epidural space at L4-5 for left and L3-4 intervertebral space for right sacral nerve (

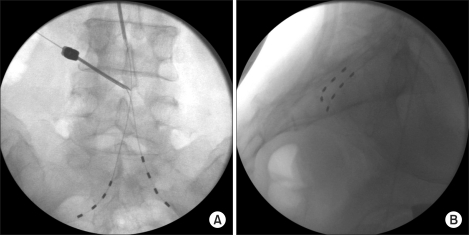

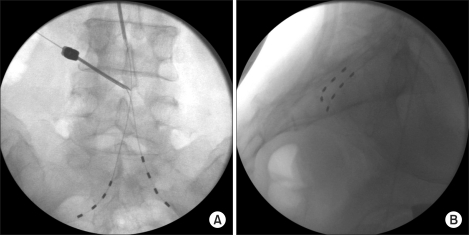

Fig. 1A). Tuohy needle was inserted superiorly and obliquely to the interlaminar space rather than inferiorly and is advanced in a caudal or transspinal direction using fluoroscopic guidance. After confirming the insertion of needle into the epidural space under fluoroscopic guidance, bilateral quadripolar leads were threaded through the needle cephalocaudally (also called, retrograde approach), and placed parallel with sacral nerve roots. And then paresthesia was checked in the painful area at 0.8-2.0 V, with a pulse width of 210 µsec, at a frequency of 30 Hz. After adjusting locomotion and stimulation, we put the leads transforaminally within S2 using fluoroscopic guidance (

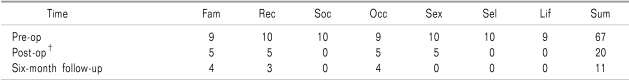

Fig. 1B). She described her NRS score as 0 out of 10 on stimulation and was satisfied with efficacy of nerve stimulator. In 7 days of trial, the permanent pulse generator (Medtronic INC., Minneapolis, MN, USA) was implanted in the left lower quadrant of abdomen (

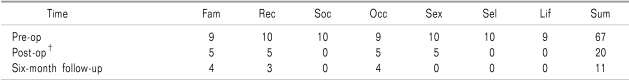

Fig. 2). She had been painless for five months and at six-month later after implantation, her NRS score was 1-2 out of 10. She has been satisfying with the efficacy of SNS and was taking medications including tramadol 150 mg, nortriptylline 75 mg and pregabalin 450 mg. We checked PDI in this patient at three times (pre-operative, immediate after operation, 6-month follow-up). Notably, almost every category of PDI was markedly improved consecutively (

Table 1).

| Fig. 1Fluoroscopic images of anteroposterior (A) and lateral (B) projections. (A) The right-sided quadripolar electrode is placed via 15-gauge Tuohy needle at L3-4 intervetebral space, and left-sided electrode is threading via another needle at L4-5 intervertebral space. (B) Fluoroscopic lateral view; each quadripolar electrode is placed at bilateral S2-3 foramen.

|

| Fig. 2A post operative abdominal anteroposterior X-ray image. A permanently implanted pulse generator is shown at left lower abdominal quadrant.

|

Table 1

Detailed Pain Disability Index (PDI)*

Go to :

DISCUSSION

Pelvic pain including anorectal pain may caused by gynecourological and coloproctolgic pathologic conditions, such as endometriosis, adnexal abnormalities, inflammatory bowel disease, hemorrhoids, anal fissure, cryptitis, prostatitis, pudendal neuropathy, interstitial cystitis, or malignant lesions [

1]. Hence, it is of paramount importance to exclude thoroughly all organic causes for the pain prior to relegation of the patient into the frustrating group labeled as having chronic intractable anorectal pain. When the origin of pain or the pathophysiological mechanism is uncertain, the term as functional anorectal pain syndrome [

1] can be used.

Though uncontrolled studies suggest that electrogalvanic stimulation, biofeedback training, digital massage of the levator ani muscles and sitz baths may be effective, the management of chronic intractable anorectal pain can be a "frustrating endeavor" [

10]. In several literatures [

2,

3], the significant efficacy of neurolytic sympathetic block of the superior hypogastric plexus to treat pelvic pain has been reported. Blockade of the ganglion impar (ganglion of Walther) has been introduced as alternative means of managing intractable neoplastic perineal pain of sympathetic origin [

11]. We applied these two sympathetic nerve blocks on this patient to observe their therapeutic effect, but the effectiveness was minimal and short-lived.

Although the exact mechanisms of action are not clear, SCS is a well-established method of managing a variety of chronic neuropathic pain conditions [

9,

12]. However, several technical factors significantly limit its application to the treatment of pelvic pain. Firstly, the dorsal cerebrospinal fluid layer at the level of Conus medullaris is quite thick, significantly insulating the spinal cord from the epidural electrodes. Secondly, Conus medullaris is relatively mobile and it is difficult to maintain consistent paresthesia when stimulating this regions. Lastly, there are few large fiber afferents from the pelvis and thus stimulation at this level frequently produces paresthesias in adjacent or undesirable regions [

4,

9]. For these reasons, some lumbosacral radiculopathies, failed back surgery syndrome and complex regional pain syndrome, as well as most sacral sensory and motor conditions (pudendal neuralgia, coccygodynia, urge incontinence, etc.) cannot be effectively stimulated above T12 [

9,

13].

Since the first literature of implantation of sacral nerve stimulator for the treatment of functional urologic disorders by Tanagho and Schmidt [

5], many authors has been used a transsacral approach of SNS for the treatment of the intractable chronic pelvic or anorectal pain up to the latest reports [

6-

8]. Despite some successes, a transsacral foraminal approach of SNS has been associated with technical failures in maintaining electrode position and consistent outcomes [

4]. This may be due to a number of anatomic and physiologic possibilities: the sacral nerve roots are perpendicular to a transsacral electrode; variation of the sacral bony and neural relationships; migration of electrode; the need for perisacral open dissection for placement; and the inability to symmetrically target multiple roots [

4,

9]. As an alternative, several authors described a few cases of SNS adopting the percutaneous retrograde approach [

4,

9,

14]. This approach for SNS has a few advantages compared to percutaneous transforamenal approach by Calvillo et al. [

15]. Firstly, low rate of the lead migration, secondly, low risk of infection and lastly, good quality of targeting and maintaining of the paresthesia consistently [

9]. Feler et al. [

14] insisted that intervention at epidural space of L5-S1 intervertebral interspace may cause more frequent complications such as dural puncture and subdural electrode placement because of the posterior angulation of the sacrum, and should be reserved for open sacral paddle placement. Furthermore, several authors reported most patients with pelvic pain syndromes had been observed a favorable response to bilateral S2 and/or S3 electrodes [

4,

9,

16]. For these reasons, we selected the cephalocaudal approach of placing the electrode at L4-5 intervertebral space for left S2 nerve root, and at L3-4 intervertebral space for right S2 nerve root and threaded toward bilateral S2 foramen and there was the optimal paresthesia at painful area and the greatest reduction of pain was felt at this level. Patient in this case showed dramatic reduction of NRS score and marked improvement of PDI score (

Table 1). And she has been satisfying with this SNS at the time of 6-month follow-up.

In this study, we suggest that the chronic anorectal pain can be successfully managed by the cephalocaudal (retrograde) approach of SNS when the symptom is recalcitrant for diverse therapeutic modalities. But the long-term prospective and controlled studies are needed to evaluate the efficacy of SNS for the chronic intractable anorectal pain.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download