This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

There are several previous reports that infection or reactivation of varicella zoster virus (VZV) can occur after coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2). Herein, we report a rare case of VZV meningitis in breakthrough COVID-19. An 18-years-old male visited the emergency room, presenting with a headache and fever of up to 38.4°C for 5 days. He received the second dose of BNT162b2 mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccine 7 weeks prior to symptom onset. The symptoms persisted with headache, fever, and nausea. His cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) showed an elevated opening pressure of 27 cm H2O, 6/µL red blood cells, 234/µL white blood cells (polymorphonuclear leukocytes 3%, lymphocytes 83%, and other 14%), 43.9 mg/dL protein, and 59 mg/dL glucose, and CSF polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test was positive for VZV. Also, he was diagnosed with COVID-19 by reverse transcriptase-PCR examining upper and lower respiratory tract. We administered intravenous acyclovir for 12 days, and he was discharged without any neurologic complication.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Varicella-Zoster Virus, Meningitis

INTRODUCTION

Emerging evidence suggests that varicella zoster virus (VZV) infection can occur after coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2).

12 VZV co-infection with SARS-CoV-2

34 or after BNT162b2 mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccination has been reported recently.

567 Though the mechanism of VZV co-infection in COVID-19 is not fully understood, decreased cellular immunity and inflammation after SARS-CoV-2 infection is suggested as a possible cause of VZV infection.

89 Since VZV infection is dependent on cell-mediated immunity, COVID-19 may promote the VZV infection.

189 Because VZV can cause severe neurologic complications such as stroke, myelitis, and neuropathy,

10 concomitant VZV infection should be noted in COVID-19 patients.

However, VZV meningitis with COVID-19 in an immunocompetent patient who already received COVID-19 vaccination has not been reported previously. Herein, we report a rare case of VZV meningitis in breakthrough COVID-19.

CASE DESCRIPTION

An 18-years-old male visited the emergency room, presenting with a headache and fever up to 38.4°C for 5 days. He reported throbbing headache of numeric rating scale 7 and nausea. He received a second dose of BNT162b2 mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccine 7 weeks prior to symptom onset. He had a history of hospitalization due to meningitis of unknown etiology at the age of 6 and no history of chickenpox. He received varicella vaccination in his childhood. The initial reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay for SARS-CoV-2 from his upper respiratory tract was negative at the emergency room. One day later, he visited to the neurology clinic with persisting headache. On examination, his vital signs were stable (blood pressure, 148/82 mmHg; heart rate, 88 bpm; respiratory rate, 20/min; and temperature, 36.2°C) and neurologic signs were normal without definite meningeal irritation. He did not have shingles or other skin lesions. We admitted him given his ongoing headache, suspecting meningitis.

On admission day, his chest X-ray (CXR) and blood tests were normal. His brain magnetic resonance imaging and angiography showed no abnormalities. His cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) showed an elevated opening pressure of 27 cm H2O, 6/µL red blood cell (RBC), 234/µL white blood cell (WBC) (polymorphonuclear leukocytes [PMNs] 3%, lymphocytes 83%, and other 14%), 43.9 mg/dL protein, and 59 mg/dL glucose. CSF PCR test was positive for VZV and negative for other pathogens, including SARS-CoV-2. Serum IgG for VZV was positive, but IgM was negative. Besides, we repeated RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 at admission, examining upper and lower respiratory tract, and they were positive.

We isolated the patient and administered 800 mg (10 mg/kg) acyclovir intravenously three times daily. A day after admission, his headache, fever, and myalgia had improved. Follow-up CXR was also normal, without pneumonic infiltration. On hospitalization day 10, we performed follow-up spinal tap. CSF analyses showed normal opening pressure of 14 cm H

2O, 0/µL RBC, 53/µL WBC (PMNs 0%, lymphocytes 95%, and other 5%), 35.9 mg/dL protein, and 61 mg/dL glucose. CSF PCR test was negative for VZV and other pathogens, including SARS-CoV-2. We performed serial SARS-CoV-2 PCR tests of the upper respiratory tract every 3 days during admission; they were consistently positive. However, after his symptoms entirely resolved, it was considered not transmittable, and he was discharged without any complications.

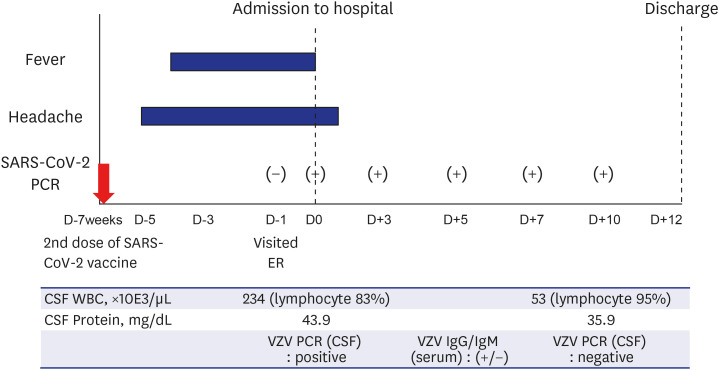

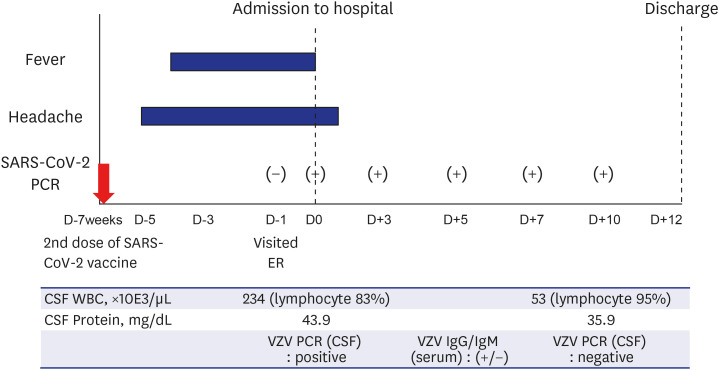

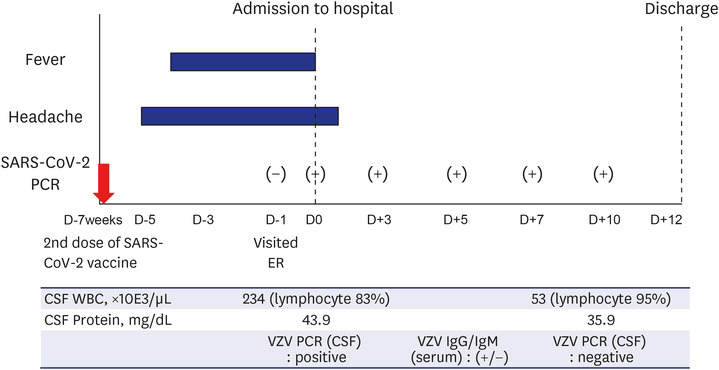

Fig. 1 describes the clinical course briefly.

Fig. 1

Clinical course of the patient. We described the major symptoms (headache and fever) and test results of the patient. He presented 5 days of headache and 4 days of fever at the admission. The initial CSF study showed positive PCR for VZV. Reverse transcriptase-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 were persistently positive during the admission. The follow-up CSF analyses at day 10 turned out to be negative PCR for VZV.

SARS-CoV-2 = severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2, PCR = polymerase chain reaction, CSF = cerebrospinal fluid, WBC = white blood cell, VZV = varicella zoster virus, ER = emergency room.

Ethics statement

We received study approval from Dankook University Hospital’s Institutional Review Board (2021-10-031). The requirement of informed consent was waived by the committee.

DISCUSSION

We reported the case of an immunocompetent patient who had concomitant breakthrough COVID-19 with VZV meningitis. CSF PCR revealed VZV co-infection without neuroinvasion of SARS-CoV-2.

There are several reports that VZV infection can occur during SARS-CoV-2 infection.

134 VZV infection or reactivation is known to be associated with hyper-inflammatory status and immune dysregulation linked to COVID-19.

18 SARS-CoV-2 impairs the function of CD4+ T cells and promotes excessive activation and subsequent exhaustion of CD8+ T cells.

19 As T cell-mediated immunity is crucial to prevent VZV infection, SARS-CoV-2 infection could be promote VZV infection.

189

BNT162b2 mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccination is also known to increase the risk of VZV infection by different mechanisms.

567 After vaccination, the cellular immune response is activated, especially CD8+ and CD4+ T cells.

567 Despite increased immune response, expression of toll-like receptors is decreased by the mRNA vaccine; this may contribute to vulnerability to VZV infection due to impaired antigen expression.

56 However, the immune response in COVID-19 breakthrough cases and difference with non-vaccinated patients are not well understood.

In addition, there are several reports suggesting that incidence of VZV infection has been increasing after COVID-19 pandemic.

2 Though the definite mechanism of this phenomenon is not well understood, it may be related to decreased exposure to viral infections. In COVID-19 pandemic, nonpharmaceutical interventions, such as wearing facial masks, hand hygiene, and social-distancing, reduced incidence of respiratory viral infections.

11 The decreased exposure to virus may have resulted in decreased anti-viral immunity, and increased innate viral reactivation such as VZV. Further studies evaluating anti-viral immunity is needed to establish increased VZV infections during COVID-19 pandemic.

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection that potentially resulted in VZV meningitis in an immunocompetent patient. Further research should be conducted to reveal the inflammatory mechanism of VZV co-infection with SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection.

We reported a rare case of VZV meningitis in breakthrough COVID-19. Because VZV infection can occur even in breakthrough COVID-19, we should be aware of the concomitant VZV infection in COVID-19 patients.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download