INTRODUCTION

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is one of the most common chronic illnesses; however, the etiology and pathogenesis of the disease remain largely unknown. One subset of CRS patients are those with eosinophilic CRS. These patients are the most refractory to medical and surgical intervention, and the condition is thought to reflect an inflammatory process arising from a variety of etiologies [

1]. Numerous stimuli, including fungal antigens, allergens, bacteria, and bacteria-derived superantigens, may be involved in the pathophysiology of this disorder [

2].

In 1981, Millar et al. [

3] first described sinus specimens from CRS patients that showed histological similarities to allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. In 1983, Katzenstein et al. [

4] independently demonstrated the presence of clusters of necrotic eosinophils, Charcot-Leyden crystals, and septate fungal hyphae in the sinus mucus of patients who had undergone sinus surgery for the treatment of CRS. They termed this material 'allergic mucin,' and introduced the term 'allergic

Aspergillus sinusitis.' Later, Robson et al. [

5] introduced the term 'allergic fungal sinusitis' after it was recognized that other species of fungi were growing in cultures of sinus specimens from these patients.

IgE-mediated and possibly type III hypersensitivity to fungi in an atopic host have been postulated as a pathogenic mechanism in allergic fungal rhinosinusitis (AFRS) [

6]. The resulting allergic inflammation leads to obstruction of the sinus ostia, which may be accentuated by anatomical factors, including septal deviation or turbinate hypertrophy, resulting in stasis within the sinuses. This, in turn, creates an ideal environment for the further proliferation of the fungus, resulting in the production of allergic mucin. The accumulation of allergic mucin obstructs the involved sinuses and further exacerbates the problem [

6].

Grossly, allergic mucin is thick, tenacious, and highly viscous in consistency and light tan to brown or dark green in color. Histologically, this mucin is defined by the presence of lamellated aggregates of dense inflammatory cells, mostly eosinophils and Charcot-Leyden crystals, the by-products of eosinophils. Originally, the term allergic mucin was based on the historic association of eosinophilia and an IgE mediated allergy. However, it is now recognized that it occurs without any detectable IgE-mediated allergy. Thus, the terminology has been changed to the more descriptive eosinophilic mucin [

7].

The classic and still widely accepted diagnostic criteria for AFRS were described by Bent and Kuhn [

8], who suggested the following: type 1 hypersensitivity by history, skin tests, or serological testing, nasal polyposis, characteristic findings on computed tomography (CT) scans, eosinophilic mucin without fungal invasion into sinus tissue, and positive fungal staining of sinus contents. However, substantial confusion exists in the categorization of fungus-related eosinophilic rhinosinusitis. Some cases of CRS have eosinophilic mucin but no detectable fungi in the mucus. These have been termed variously as 'allergic mucin but without fungal hyphae,' [

9] 'allergic mucin sinusitis without fungus,' [

10] and 'eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis' (EMRS) [

11]. On the other hand, some patients have the clinical features of AFRS with a positive fungal culture or staining from their eosinophilic mucin, but no systemic evidence of a fungal allergy [

12,

13]. Although it is a relatively rare condition, an AFRS-like syndrome with a systemic fungal allergy but negative fungal staining or culture has also been described [

12].

The confusion is heightened further by the alternative hypothesis of Ponikau et al. [

14] In 1999, they demonstrated the presence of fungi in mucus from 93% of surgical cases with CRS, yet a fungus-specific allergy was uncommon in these patients. Thus, they proposed an alternate theory that most CRS patients fulfill the criteria for AFRS despite lacking IgE fungal hypersensitivity. Over the ensuing decade, this 'fungal hypothesis' of CRS pathogenesis has had its share of supporters and detractors [

15]. Presently, however, most experts prefer to maintain the distinction between AFRS and CRS [

15,

16].

It is known that the pathophysiological presentation of CRS differs by race, geographic region, and climate. Most CRS cases show eosinophil-dominant inflammation in Europe and the United States (US), but more than half of CRS cases do not in Korea and East Asia [

17,

18,

19]. The incidence of AFRS has been estimated at 5%-10% of all CRS patients undergoing surgery in the US [

6,

20,

21], but it is relatively rare in Korea. For these reasons, to date, there have been few studies on CRS with eosinophilic mucin in a Korean population.

The aim of this study was to categorize CRS patients with characteristic eosinophilic mucin treated in the Department of Otorhinolaryngology at Chungnam National University Hospital (Daejeon, Korea) into several groups and to compare their clinicopathological features.

Go to :

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chungnam National University Hospital. Patients who demonstrated CRS with characteristic eosinophilic mucin and were treated in the Department of Otorhinolaryngology at Chungnam National University Hospital between 1999 and 2012 were reviewed. Patients were selected only if they underwent a histopathological examination of harvested mucin, a skin prick test and/or serological tests against multiple aeroallergens, including fungal antigens, and CT scanning of the paranasal sinuses in the axial and coronal planes. In total, 52 patients were identified and included in this study.

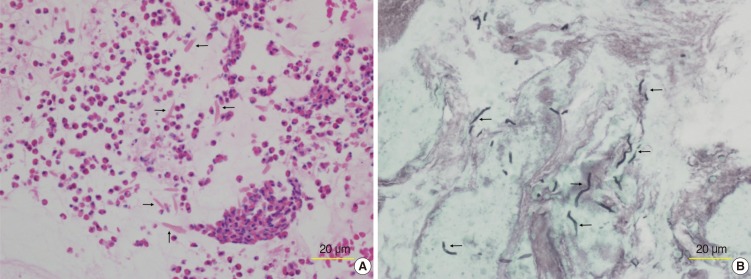

All patients had visible characteristic mucin. At the time of surgery or nasal endoscopic examination, thick sticky mucin was collected meticulously for histopathological examination. To ensure maximum mucin collection, the use of microdebrider and suction devices was limited. The mucin was manually removed using forceps or curettes. Histological sections were prepared in the usual manner with fixation in 10% neutral buffered formalin and routinely stained with hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid-Schiff, and Grocott's methenamine silver stain to detect fungal organisms (

Fig. 1). We encouraged our pathologists to completely examine the mucin we harvested.

| Fig. 1Histologic section from a patient with allergic fungal rhinosinusitis. (A) Micrograph of eosinophilic mucin showing clusters of eosinophils and numerous Charcot-Leyden crystals (arrows) within a background of amorphous mucin (H&E). (B) Grocott's methenamine silver staining revealed darkly stained fungal hyphae (arrows) within the eosinophilic mucin.

|

Allergic status was confirmed by skin prick tests, multiple allergosorbent tests (MAST), or the ImmunoCAP system (Phadia, Uppsala, Sweden) against aeroallergens, including house dust mites, pollen, animal dander, and fungi. The total serum IgE level and absolute eosinophil count were also measured. An eosinophil count >500 cells/µL was considered to indicate eosinophilia. A complete blood cell count with differential count was done as part of the preoperative evaluation in all patients.

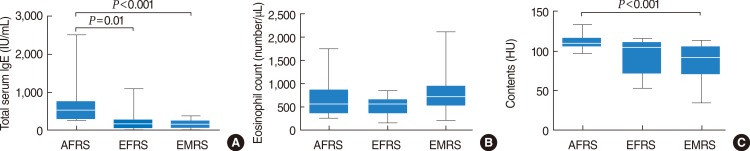

The CT scans were evaluated for the presence of intrasinus high attenuation areas, the extent of sinus involvement, sinus wall expansion, bony erosion or thinning, and extension of the disease into adjacent soft tissues. To evaluate the radiodensity of intrasinus mucin in high attenuation areas, it was quantitated in terms of Hounsfield units (HU), a quantitative scale for describing radiodensity.

On the basis of the results of fungal staining of the mucin and the presence or absence of a fungal allergy, the patients were categorized into the following four groups: AFRS, positive for a fungal allergy and positive fungal staining in mucin; AFRS-like sinusitis, positive for a fungal allergy but negative for fungal staining in mucin; EFRS, positive fungal staining in mucin but negative for a fungal allergy; and EMRS, negative fungal staining and negative for a fungal allergy. A total of 13 patients were placed in the AFRS group, 13 in the EFRS group, and 26 in the EMRS group. No patient was assigned to the AFRS-like sinusitis group.

The medical records of the patients were reviewed for the following information: age at the time of presentation, sex, previous surgery, allergic rhinitis, bronchial asthma, presenting symptoms, differential eosinophil count, absolute eosinophil count, total serum IgE, CT findings, unilateral versus bilateral disease, treatment modalities, and outcome.

PASW ver. 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. A chi-square test was used to assess differences between groups in terms of sex, history of previous surgery, the presence of allergic rhinitis, asthma, unilateral disease, presenting symptoms, and radiological findings. A one-way analysis of variance was used to compare ages, total serum IgE, differential eosinophil counts, and sinus contents (in HU) between groups. In all cases, a P-value <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Go to :

DISCUSSION

CRS with eosinophilic mucin encompasses a wide variety of etiologies and associations. Recently, the International Society for Human and Animal Mycology Working Group attempted to categorize CRS with eosinophilic mucin into subgroups [

7]. However, this classification scheme is still incomplete and requires better definition. In this study, we categorized patients with CRS and eosinophilic mucin into four groups (AFRS, AFRS-like sinusitis, EFRS, and EMRS), depending on the presence or absence of fungi in the eosinophilic mucin and a fungal allergy, and we compared their clinicopathological features.

Ramadan and Quraishi [

10] reported that patients with AFRS were younger than those with allergic mucin sinusitis. Ferguson [

11] also found that the mean age of patients with AFRS was significantly lower than that of patients with EMRS. In the present study, the patients with AFRS tended to be younger than the patients in the other groups, but the difference was not statistically significant. All groups showed a slight male predominance, with no statistically significant difference between the groups.

Patients with AFRS frequently demonstrate hypersensitivity to house dust mites, pollen, and other antigens [

6,

11,

22]. In the present study, 84.6% of patients with AFRS demonstrated positive skin tests and in vitro (MAST and ImmunoCAP) responses to nonfungal aeroallergens. In contrast, only 30.8% of the EFRS group and 34.6% of the EMRS group showed allergic rhinitis.

Ferguson [

11] reported that 41% of patients with AFRS were asthmatic, compared with 93% of patients with EMRS. Another study noted that 100% of patients with allergic mucin sinusitis without hyphae had asthma, whereas only 25% of patients with AFRS had asthma [

10]. In the present study, similar results were seen; 65% of patients with EMRS were asthmatic, while only 1 patient (8%) in the AFRS and EFRS groups had asthma.

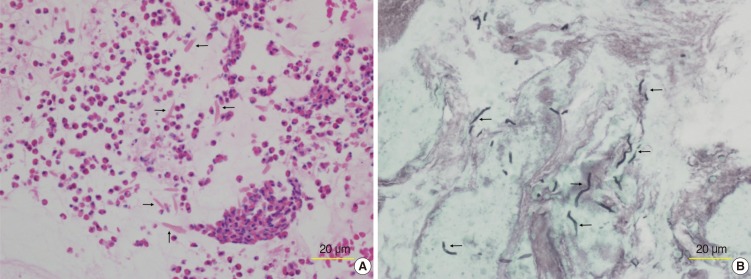

Total IgE values are known to be increased in patients with AFRS, occasionally to >1,000 IU/mL [

12,

21]. Several reports have shown significantly higher IgE levels in AFRS patients compared with EMRS or CRS patients with other forms of the disease [

11,

16]. A similar result was demonstrated in the present study. Total serum IgE levels were significantly higher in the AFRS patients compared with the EFRS and EMRS patients. Regarding eosinophilia, 69% of patients with AFRS, 54% of EFRS, and 77% of EMRS patients showed it; however, there was no significant difference in eosinophil count between the groups.

Most studies have shown that AFRS presents frequently as a unilateral disease [

11,

23]. Ferguson [

11] reported that EMRS was not found as a unilateral disease process, while AFRS was unilateral in almost half of all cases. In the present study, 69% of patients with AFRS and EFRS had unilateral disease, while all of the patients with EMRS had bilateral disease.

The presenting clinical complaints of these patients are usually nonspecific and consist primarily of symptoms of chronic sinusitis, including nasal obstruction, nasal discharge, sneezing, and postnasal drip. However, diminished olfaction was more frequent in patients with EMRS compared with the AFRS and EFRS patients. This may be due to more frequent bilateral multiple sinus involvement and association with asthma in patients with EMRS. Conversely, pain or pressure was more frequent in patients with AFRS and EFRS compared with patients with EMRS. The reason for this is unknown, but it may involve the amount and viscosity of mucin. Lara and Gomez [

24] demonstrated that the amount of allergic mucin was much greater in patients with a fungus than in patients without.

The accumulation of eosinophilic mucin in the paranasal sinuses may become an expansile mass, leading to complications [

25]. Visual symptoms, proptosis, headaches, facial dysmorphia, and increased nasal symptoms suggest the development of complications. However, we did not experience a case with such complications.

Sinus CT findings in AFRS include areas of high attenuation within the opacified sinuses that correspond to eosinophilic mucin [

6,

25]. This high attenuation in AFRS is likely due to a combination of heavy metals, calcium, and inspissated secretions [

6,

23]. In the present study, areas of high attenuation were found within the sinuses in all patients with AFRS, while 77 and 73% of patients with EFRS and EMRS showed them, respectively. A statistical analysis regarding the prevalence of high attenuation areas revealed a significant difference between the AFRS and EMRS groups. The mean HU score in the areas of high attenuation in the AFRS patients was significantly higher than that in the EMRS patients.

In AFRS patients, bony demineralization of the sinus wall may ensue, resulting in thinning of the sinus wall, expansion of the sinus, and bony erosion. Most authors believe that bone erosion is due to pressure atrophy by accumulating mucin and possibly to the effects of inflammatory mediators, rather than to fungal invasion [

26]. Nussenbaum et al. [

27] reported that true bone erosion and extension of the disease into adjacent anatomical areas was encountered in approximately 20% of patients with AFRS. In the present study, three patients (23%) with AFRS had erosion of the bony wall and expansion of the sinus, while only one patient in the EFRS and EMRS groups showed bony erosion and expansion of the sinus.

The treatment modalities are similar for AFRS, EFRS, and EMRS. Treatment requires surgery and aggressive postoperative medical management with close follow-up [

20,

21]. Surgery is indicated as the first-line treatment. Endoscopic surgery is sufficient to evacuate inspissated mucin and to facilitate continued sinus drainage. Systemic corticosteroids have been advocated in the initial treatment of AFRS [

28]. Presently, however, the optimal dose and length of therapy remain unclear.

We treated all but 2 patients with endoscopic sinus surgery; 37 of these patients received oral corticosteroids postoperatively. Two patients with AFRS were treated initially with oral corticosteroids alone. Of patients who had been followed for >6 months, 81% showed recurrence. There was no significant difference in recurrence rate between the groups. Recurrent cases were treated with multiple courses of oral corticosteroids, revision surgery, and revision surgery with oral corticosteroids. However, some patients still had persistent disease. Thus, long-term follow-up is essential regardless of the form of therapy chosen.

In the present study, two limitations may exist to categorize exactly the patients with CRS and eosinophilic mucin into four subgroups. One is for the detection of fungal hyphae in the eosinophilic mucin, and the other is for the demonstration of IgE-mediated hypersensitivity. Thus, there may be considerable overlap between the groups. Nevertheless, each group had distinctive features.

The AFRS patients were more likely to have an inhalant allergy, and to have higher total serum IgE levels. They presented frequently with unilateral disease, and all of them showed high attenuation areas with higher HU scores on CT scans. Thus, the pathophysiology of AFRS is most consistent with chronic, intense allergic inflammation directed against colonizing fungi.

The EFRS patients were similar to the AFRS patients in several aspects. They presented frequently with unilateral disease and showed a significantly lower frequency of asthma. However, they showed a lower incidence of allergic rhinitis and significantly lower total serum IgE levels than the AFRS patients. The pathogenesis of this entity is unknown, but emerging evidence suggests that locally produced fungal-specific IgE may be involved [

12].

The EMRS cases were uniformly bilateral and showed a significantly higher frequency of asthma and significantly lower frequency of allergic rhinitis with significantly lower total serum IgE levels compared with the AFRS patients. Olfactory disturbances were more frequent in the patients with EMRS compared with the AFRS and EFRS patients. The prevalence of high attenuation areas and the mean HU scores for the sinus contents were significantly lower than in the AFRS patients. Thus, EMRS is thought to be a systemic disease having a distinct immunological pathogenesis.

In summary, significant clinical and immunological differences exist among the subgroups of CRS with eosinophilic mucin. Future studies may provide clues to understand the pathophysiological basis of these differences.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download