Abstract

Objectives

Pharyngocutaneous fistula is a serious complication after total laryngectomy, and there are some risk factors stated in the literature. The surgical suture techniques are not studied so much. The aim of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of 'modified continuous mucosal Connell suture' on the incidence of pharyngocutaneous fistula after total laryngectomy.

Methods

This is a retrospective case series study based at a tertiary center with 31 patients who underwent total laryngectomy between July 2011 and December 2013. Pharyngocutaneous fistula formation after total laryngectomy was evaluated with the patients who underwent modified continuous mucosal Connell suture for pharyngeal repair.

Results

Pharyngocutaneous fistula was observed in only one patient (3.2%) who had a history of previous radiotherapy, and it was spontaneously healed within 6 days by conservative treatment.

Conclusion

We defined a new suture technique for the pharyngeal repair after total laryngectomy. This technique is a simple modification of continuous mucosal Connell suture. We named it as zipper suture. It is effective in the prevention of pharyngocutaneous fistula for pharyngeal reconstruction after total laryngectomy.

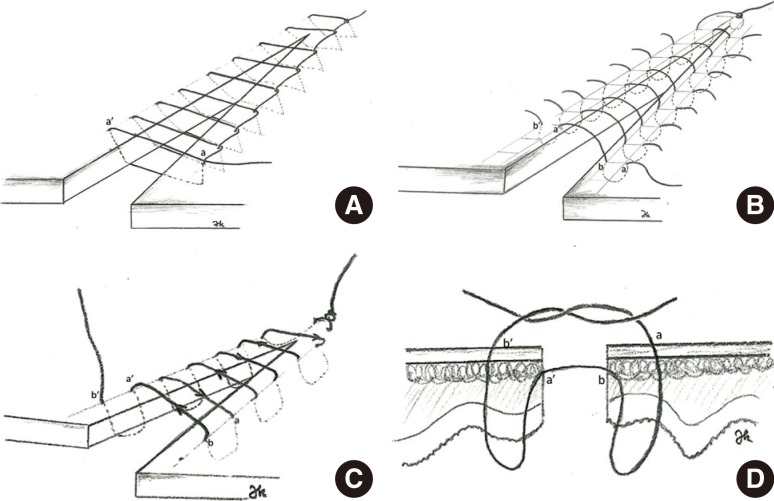

Pharyngocutaneous fistula (PCF) is one of the most troublesome complications in early postoperative period after total laryngectomy. It increases the morbidity and hospital stay significantly. The reported incidence of PCF ranges from 3% to 65% [1]. In the literature, several risk factors such as; preoperative radiotherapy, the type of surgery, concurrent radical neck dissection, the suture material used for pharyngeal reconstruction, the presence of residual tumor, previous neck surgery, preoperative tracheotomy, poor general conditions, the site of tumor origin, intraoperative blood transfusion, low postoperative hemoglobin level, the type of neck drainage, preoperative weight loss, wound infection, postoperative vomiting, and hematoma formation have been proposed to be predisposing to PCF [2]. However, the effect of stitch technique used in the closure of pharyngeal mucosa to the PCF formation has not been studied yet widely. There are a limited number of papers in the literature that compare the manual and mechanical sutures regarding the stitch techniques for pharyngeal repair after total laryngectomy [345]. The surgical steps of a manual closure technique for pharyngeal defect were not clearly defined in any of those studies. As a surgeon can use his/her own technique for pharyngeal closure, the classical and well known stitch techniques do not exceed the number of count of fingers of one hand. Four different stitch techniques; continuous interlocking, Lembert, Connell, and Gambee are demonstrated on the Fig. 1. Any of these techniques, particularly Connell suture can be used for manual pharyngeal closure [6]. Our literature search did not reveal any studies comparing those stitches to each other in terms of PCF formation in total laryngectomy patients.

The aim of this study was to define a new pharyngeal suture technique and present its surgical results on PCF after total laryngectomy. This stitch method is a simple modification of continuous Connell suture. The surgical steps and possible advantages of this stitch technique were discussed in this paper.

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of study center. Thirty one patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma have undergone total laryngectomy operation between July 2011 to December 2013 at the Department of Otolaryngology, Bursa Sevket Yilmaz Training and Research Hospital. A simple modification of continuous mucosal Connell suture which subsequently named as zipper suture was used for pharyngeal closure in all of the patients. The patients were staged using American Joint Committee on Cancer cancer staging manual 2010 [7]. The medical records of patients were reviewed retrospectively in terms of the development of PCF.

A standard total laryngectomy with/without neck dissection was performed to all patients. After total laryngectomy, a nasogastric tube was inserted for postoperative feeding before starting the pharyngeal closure. Then, two independent sutures were applied to the corners of pharyngeal defect in the horizontal plane. The ends of suture were tensioned to the right/left sides of pharynx with a forceps and the closure shape of pharynx (horizontal or T type) was determined with this manner (Fig. 2A). Starting from one corner of pharyngeal defect, the continuous modified Connell suture (zipper suture) was applied to all wound edges.

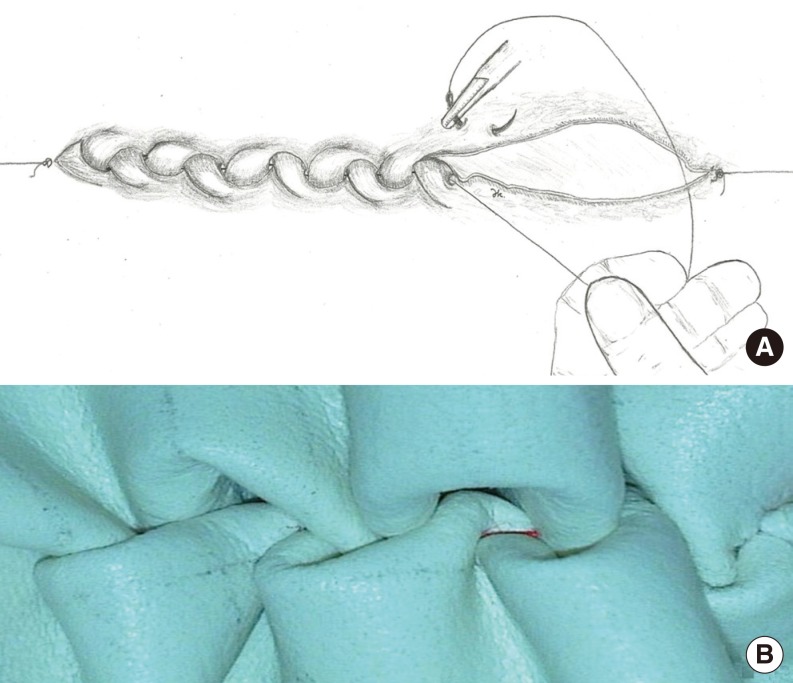

Continuous modified Connell technique (zipper suture) was a simple modification type of continuous Connell suture [6]. The suture material used in all cases was 3/0 vicryl with a round needle. Two points (a and b on one side, a1 and b1 on the corresponding side, Fig. 2B) were determined at the wound edges near (-0.5 mm) and a little distant (-1 mm) to the suture line. These points were not on the same line vertically and horizontally (Fig. 2B). To achieve that, the acceptable distance (shown by χ in Fig. 2B) should be adjusted between every consecutive needle insertion point in horizontal and vertical plane. These points were simply adjusted by the curve of needle in the oblique fashion, with the sense of proportion. Firstly, the needle was inserted from extra mucosal site to the mucosal side at the lateral point, then it was took off from the mucosal side to the extra mucosal side at the medial point in the oblique plane with a single maneuver, while the mucosal edge was gently pinched and lifted with the fine forceps (Fig. 3). We mentioned this sewing pattern as 'far outside in and near inside out' as demonstrated in Fig. 4. Before and after every stitch, the free end of completed suture should be secured in tension by another surgeon to provide spontaneous inversion of the mucosa (Fig. 5). The pharyngeal defect was sutured horizontally with only one-piece of vicryl. When T type closure was required a second vicryl lsuture has been used for the vertical portion (Fig. 6). After the completion of suturing, the free end of vicry lwas knotted tightly to the end of defect to prevent the relaxation. Then, it was supported by second or third layers with single sutures in a manner that does not interrupt the blood supply.

Hemovac drains were placed under the skin flaps on each side of the neck. The circumferential neck dressing was routinely used for 4-6 days postoperatively to provide a gentle pressure to the skin flaps to avoid any collections. The drains were taken out on postoperative 3rd-5th day, when the drainage is less than 15-20 mL per drain. The circumferential neck dressing was applied for additional 2 days to prevent de-attaching of skin flaps from underlying tissue.

All cases were fed via nasogastric tube with gavage during postoperative 11 days. Oral feeding was started on 12th postoperative day firstly with milk to control any possible fistula. PCF was diagnosed when the drainage of saliva was noted under the skin flaps during postoperative 11 days or a reflux was detected around the stoma or suture line after the first oral intake of milk. For the treatment of PCF, oral intake was totally restricted and wound care consisting of debridement of the orifice of fistula and pressure dressings were applied daily as the conservative treatment. The successful healing of PCF was defined in the presence of no signs of fistula.

The study included 31 patients (29 males, 2 females; mean age, 60 years; range, 45 to 73 years). All patients were smoker. The number of patients with T3 and T4 tumor were eight (25.8%) and 23 (74.2%) respectively (Table 1). Two patients (6.45%) had recurrent tumor after the failure of radiotherapy. Primary tumor locations, surgical and clinical features of the patients are summarized in Table 1. Standard total laryngectomy with bilateral neck dissection was performed to 29 patients (93.5%). Two patients (6.4%) who had previously received radiotherapy underwent total laryngectomy without neck dissection. There was no evidence of distant metastasis in any patients preoperatively.

PCF occurred in only one patient on postoperative 7th day thathad a history of preoperative radiotherapy. It was managed conservatively and the fistula was healed within 5 days. No major other complications were observed in any cases.

PCF is a serious complication after total laryngectomy, and its etiology is not well understood yet. Up to now, studies in the literature have focused on the some factors related to PCF formation. Many factors (previous radiotherapy, intraoperative blood transfusion, postoperative hemoglobin level, general conditions, and preoperative weight loss) have been proposed to cause PCF, but there is no consensus on the etiologic factors (related to the patient, the tumor, and the treatment) of PCF. Also, the types and techniques of mucosal stitch for the repair of the pharyngeal defect after total laryngectomy have not been studied enough. Connell, Gambee, Lembert, and continuous interlocking sutures are well-known and commonly used techniques for the mucosal closure [6]. However, there are no detailed descriptive data and evaluations about the steps of stitch technique used for pharyngeal closure in the literature.

In the present study, we focused on the stitch technique and presented a new mucosal suture technique named as zipper suture, a simple modification of continuous Connell suture.

The incidence of PCFs after total laryngectomy has been reported between 3%-65% in the previous studies [1]. The rate of PCF after total laryngectomy has been reported between 13%-25% over the last two decades [2]. However, it was lower than 10% in only a few reports.

We have previously used Gambee stitch technique for pharyngeal closure. The rate of PCF in that study was 35.9% [8]. PCF rate in the present study was found as 3.2% (1/31). Zipper suture technique showed one of the lowest rate of PCF when compared to literature (Table 2) [891011121314151617]. The demographic and medical data of our cases are demonstrated in Table 1. These are somewhat similar to the studies in the literature. Since the number of the case is limited in present study, multivariate analyses of other risk factors (previous radiotherapy, tumor stage and location, postoperative hemoglobin level, general conditions, and preoperative weight loss, etc.) on PCF formation could not be studied. Our aim was to present the zipper suture technique and its impact on pharyngeal closure.

In the present study, the only case with complication of PCF had a history of preoperative radiotherapy. Additionally, he had started oral feeding at postoperative 2nd day in secret to himself. A PCF with low flow was noticed at 7th day postoperatively. Oral intake was totally restricted and the wound care consisting of debridement of the orifice of fistula and pressure dressings were applied daily as the conservative treatment and the PCF was healed completely at 12th postoperative day. The incidence of PCF among nonirradiated patients was actually 0.0% (0/30) in the present study.

A comprehensive review of the literature showed different and controversial results about the incidence of PCF (Table 2). Many different factors also have been accused in the development of fistula. For example, there was no statistical correlation between the radiotherapy and the incidence of PCF in a study [2], whereas previous radiotherapy was blamed as a causative factor in another study [1]. Most of those cofactors are related to the patient, and are unavoidable before surgery. At the same time, many of them cannot be completely eliminated. Previous neck surgeries, preoperative tracheotomy, poor general conditions, the site of tumor are inevitable and unchangeable, either may be present or absent at the time of the surgery. On the other hand the surgical technique to be used for the repair of the pharynx is in the hands of the surgeon.

The accurate pharyngeal repair with water tight suture made in three layers was indicated as the mainstay on the prevention of fistula following laryngectomy [18]. The PCF complication was not observed in 44 consecutive laryngectomy cases in that study. Some authors considered the suture material, surgical technique, and surgeon's ability as predisposing factors to PCF [1920], but in the study of Galli et al. [21] no statistical significant differences were detected between the aforementioned factors and PCF. We think the surgeon's skill, experience and ability, also the surgical technique used for the pharyngeal closure represents as important factors impacting on the eventual development of PCF.

Mechanical linear suture is another alternative technique for pharyngeal closure, which is based on the experience in surgery of Zenker's diverticulum. Many studies have reported the rate of fistula between 4%-11% with this technique [45222324]. The mechanical linear suture has a fast and simple learning curve. The general consensus on this technique is as follow; it is an easy, simple, reliable, time saving, and practical method allowing a water-tight closure of the pharynx with a low risk of contamination of the surgical field and shows a lower incidence of PCF when compared to the manual suture. Pharyngeal mucosa is not opened during this procedure. Therefore, an oncological criticism may come in to the mind along with the advantages, because of the blind tumor resection. Thus, the authors have preferred this procedure for only selected cases in endolaryngeal tumors [522].

The rate of PCF in our study was similar to the mechanical suture. It could be lesser, because, the only case that developed PCF had preoperative radiotherapy and had started oral feeding in secret to himself in early postoperative (2nd day) period.

Comparing the present study with the literature in terms of PCF rate, it may be concluded that the modified continuous Connell mucosal suture (zipper suture) is an effective method for pharyngeal closure after total laryngectomy in the prevention of PCF.

The main differences of zipper suture from Continuous interlocking Lembert, Connell, and Gambee suture techniques can be summarized as:

(1) There is one stitch point on each wound edge (a on one side and a' corresponding side shown in Fig. 1A) in continuous interlocking suture technique. But in zipper suture technique, two stitch points (a

b on one side and a' b' on the corresponding side shown in Fig. 2B) are formed on each side. This provides an enhanced touching surface between the wound edges and a thicker stitch layer at the end of first suture line.

(2) Stitch points in Lembert, Gambee, and Connell sutures are on the same line (vertically or horizontally) and parallel to the wound edges (Fig. 1B-D). But these points are not on the same line in the zipper suture technique, either vertically or horizontally (Fig. 2B). We estimate that the blood flow to the wound edges will be less affected and the congestion will be prevented, so that the blood supply will be more stable.

(3) As described in the 'surgical technique' section, for both wound edges 'far outside in and near inside out' suture pattern (Fig. 4) is important for spontaneous inversion of the wound edges, which provides a water-tight closure in zipper suture. In Lembert suture, 'far outside in and near inside out' pattern on one wound edge, and (as a difference from zipper suture) 'near outside in far inside out' pattern on the corresponding side are applied (Fig. 1B). Penetration of submucosa but not mucosa is the typical feature of Lembert suture. With the subsequent sutures the wound edges are merged to form spontaneous inversion on a single plane.

(4) Gambee suture has an interrupted stitch pattern and one knot is left at the end of every stitch at the suture line. This suture needs sufficient mucosal thickness for near stitch point. It is sometimes difficult to perform this suture properly, due to the inadequate thickness of pharyngeal mucosa (Fig. 1D).

We think the zipper suture has several positive effects on the healing of pharyngeal defect (Table 3). First, since this technique prevent the overlapping of stitch points of consecutive sutures (a

b and a' b' in Fig. 2B) the blood and lymph circulation of mucosal edges could be better. Second, this stitch technique ('far outside in and near inside out' pattern) allows spontaneous inversion of mucosal edges (Fig. 3) that is very important for a water-tight mucosal closure. Third, every stitch provides tightness and firmness to the previous one, and this support prevents the relaxation of suture line (Fig. 5). The parallel consecutive sutures, each on corresponding wound edges are joined and interlocked as a zipper. This interlocking closure pattern inspired us to name this technique as zipper suture.

We think zipper suture is simple and easy to learn. It is also a time saving procedure. Since it is a continuous suture, only one piece of straight and tight vicryl in 12- to 15-cm length is left at the suture line after completion of the first layer (Fig. 5A). Continuous suture techniques have the advantage of leaving fewer sutures at the suture line when compared to the interrupted consecutive stitches. With the reduced suture material and number of knots, the risk for foreign body reaction may be decreased. Finally, by this study we attempt to divert the physicians' attention from patient-related factors to the surgical technique.

This study has the limitation of being retrospective and including relatively small number of cases. Instead of a real control group, our results were compared to studies in literature. The opinions about the blood flow to wound edges and foreign body reaction need to be proven in the animal models histologically. As the PCF rate for salvage laryngectomy was reported high (35%-58%) in the the literature [25] the number of cases for salvage surgery was relatively fewer in this study.

In conclusion, zipper suture technique may be effective in prevention of the PCF after total laryngectomy. Comparative studies with a high number of cases are required to document the usability of this suture technique for pharyngeal closure.

References

1. Saki N, Nikakhlagh S, Kazemi M. Pharyngocutaneous fistula after laryngectomy: incidence, predisposing factors, and outcome. Arch Iran Med. 2008; 5. 11(3):314–317. PMID: 18426323.

2. Redaelli de Zinis LO, Ferrari L, Tomenzoli D, Premoli G, Parrinello G, Nicolai P. Postlaryngectomy pharyngocutaneous fistula: incidence, predisposing factors, and therapy. Head Neck. 1999; 3. 21(2):131–138. PMID: 10091981.

3. Altissimi G, Frenguelli A. Linear stapler closure of the pharynx during total laryngectomy: a 15-year experience (from closed technique to semi-closed technique). Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2007; 6. 27(3):118–122. PMID: 17883187.

4. Bedrin L, Ginsburg G, Horowitz Z, Talmi YP. 25-year experience of using a linear stapler in laryngectomy. Head Neck. 2005; 12. 27(12):1073–1079. PMID: 16265656.

5. Goncalves AJ, de Souza JA Jr, Menezes MB, Kavabata NK, Suehara AB, Lehn CN. Pharyngocutaneous fistulae following total laryngectomy comparison between manual and mechanical sutures. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2009; 11. 266(11):1793–1798. PMID: 19283399.

6. Lore JM, Medina J. An atlas of head and neck surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders;2004.

7. Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A, editors. AJCC cancer staging manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer;2010.

8. Akduman D, Naiboglu B, Uslu C, Oysu C, Tek A, Surmeli M, et al. Pharyngocutaneous fistula after total laryngectomy: incidence, predisposing factors, and treatment. Kulak Burun Bogaz Ihtis Derg. 2008; Nov-Dec. 18(6):349–354. PMID: 19293623.

9. Virtaniemi JA, Kumpulainen EJ, Hirvikoski PP, Johansson RT, Kosma VM. The incidence and etiology of postlaryngectomy pharyngocutaneous fistulae. Head Neck. 2001; 1. 23(1):29–33.

10. Grau C, Johansen LV, Hansen HS, Andersen E, Godballe C, Andersen LJ, et al. Salvage laryngectomy and pharyngocutaneous fistulae after primary radiotherapy for head and neck cancer: a national survey from DAHANCA. Head Neck. 2003; 9. 25(9):711–716. PMID: 12953306.

11. Smith TJ, Burrage KJ, Ganguly P, Kirby S, Drover C. Prevention of postlaryngectomy pharyngocutaneous fistula: the Memorial University experience. J Otolaryngol. 2003; 8. 32(4):222–225. PMID: 14587560.

12. Rubino A, Gonzalez Aguilar O, Pardo HA, Simkim D, Vannelli A, Rossi A. Posttlaringectomy fistula: factors that favour its development. Rev Argent Cir. 2005; 88(5/6):234–241.

13. Markou KD, Vlachtsis KC, Nikolaou AC, Petridis DG, Kouloulas AI, Daniilidis IC. Incidence and predisposing factors of pharyngocutaneous fistula formation after total laryngectomy. Is there a relationship with tumor recurrence? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2004; 2. 261(2):61–67. PMID: 12856129.

14. Sarra LD, Rodriguez JC, Garcia Valea M, Bitar J, Da Silva A. Fistula following total laryngectomy. Retrospective study and bibliographical review. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2009; May-Jun. 60(3):186–189. PMID: 19558904.

15. White HN, Golden B, Sweeny L, Carroll WR, Magnuson JS, Rosenthal EL. Assessment and incidence of salivary leak following laryngectomy. Laryngoscope. 2012; 8. 122(8):1796–1799. PMID: 22648757.

16. Sousa Ade A, Porcaro-Salles JM, Soares JM, de Moraes GM, Carvalho JR, Silva GS, et al. Predictors of salivary fistula after total laryngectomy. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2013; Mar-Apr. 40(2):98–103. PMID: 23752634.

17. Aires FT, Dedivitis RA, Castro MA, Ribeiro DA, Cernea CR, Brandão LG. Pharyngocutaneous fistula following total laryngectomy. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2012; 12. 78(6):94–98. PMID: 23306575.

18. Applebaum EL, Levine HL. Pharyngeal reconstruction after laryngectomy. Laryngoscope. 1977; 11. 87(11):1884–1890. PMID: 916783.

19. Lavelle RJ, Maw AR. The aetiology of post-laryngectomy pharyngo-cutaneous fistulae. J Laryngol Otol. 1972; 8. 86(8):785–793. PMID: 5044285.

20. Verma A, Panda NK, Mehta S, Mann SB, Mehra YN. Post laryngectomy complications and their mode of management: an analysis of 203 cases. Indian J Cancer. 1989; 12. 26(4):247–254. PMID: 2636211.

21. Galli J, De Corso E, Volante M, Almadori G, Paludetti G. Postlaryngectomy pharyngocutaneous fistula: incidence, predisposing factors, and therapy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005; 11. 133(5):689–694. PMID: 16274794.

22. Calli C, Pinar E, Oncel S. Pharyngocutaneous fistula after total laryngectomy: less common with mechanical stapler closure. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2011; 5. 120(5):339–344. PMID: 21675591.

23. Zhang X, Liu Z, Li Q, Liu X, Li H, Liu W, et al. Using a linear stapler for pharyngeal closure in total laryngectomy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013; 3. 270(4):1467–1471. PMID: 22986414.

24. Ahsan F, Ah-See KW, Hussain A. Stapled closed technique for laryngectomy and pharyngeal repair. J Laryngol Otol. 2008; 11. 122(11):1245–1248. PMID: 18680636.

25. Scotton WJ, Nixon IJ, Pezier TF, Cobb R, Joshi A, Urbano TG, et al. Time interval between primary radiotherapy and salvage laryngectomy: a predictor of pharyngocutaneous fistula formation. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014; 8. 271(8):2277–2283. PMID: 24132652.

Fig. 1

Four different commonly used suture techniques; continuous interlocking (A), Lembert (B), Connell (C), and Gambia (D).

Fig. 2

(A) Pharyngeal defect after total laryngectomy. (B) Schematic diagram of the modified continuous Connell suture (zipper suture). Note that the distance (shown by χ in panel B) is preserved between every following stitch, and none of following stitches are on the same line vertically and horizontally. TS, tension suture; NG, nasogastric tube.

Fig. 3

Semi closed pharyngeal defect. Note that oblige position of porteque and needle. Assistant keeps the vicryl in tension to provide inversion of mucosa and not to permit relaxation. (A) Zipper suture on synthetic material. (B) Note that the spontaneous inversion of the edges.

Fig. 4

Close-up view of the zipper suture technique. Note the stitch pattern of 'far outside in and near inside out'.

Fig. 5

Closed pharyngeal defect: schematic diagram of pharyngeal repair with zipper suture (A, B), pharyngeal repair of the case focused at suture line (C).

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical, and surgical features of the cases

| Age (year)/sex | Region | Stage* | Comorbid disease | Other specialties | Type of surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 45/M | Glottic | T3N0M0 | - | - | TL+bilateral ND |

| 65/M | Supraglottic | T4N1M0 | CB | - | TL+bilateral ND |

| 69/M | Supraglottic | T4N0M0 | CB+HT | Paraneoplastic sydrom postoperatively | TL+bilateral ND |

| 72/M | Transglottic | T4N0M0 | - | TL+bilateral ND+bilateral total thyroidectomy | |

| 49/M | Glottic+subglottic | T4N0M0 | - | - | TL+ bilateral total thyroidectomy |

| 70/M | Glottic+subglottic | T4N0M0 | CB | - | TL+bilateral ND+unilateral thyroidectomy |

| 64/M | Supraglottic | T4N2bM0 | - | - | TL+bilateral ND |

| 64/M | Supraglottic+glottic | T4N0M0 | - | - | TL+bilateral ND |

| 59/M | Supraglottic | T3NOM0 | CB | Pyriform sinus invasion | TL+bilateral ND |

| 57/M | Supraglottic | T3N2cM0 | HT | - | TL+bilateral ND |

| 55/M | Supraglottic+glottic | T3N1M0 | - | - | TL+bilateral ND |

| 59/M | Transglottic | T4N0M0 | CB | - | TL+bilateral ND+bilateral total thyroidectomy |

| 58/M | Supraglottic | T4N0M0 | DM | - | TL+bilateral ND |

| 51/M | Glottic+subglottic | T4N1M0 | - | - | TL+bilateral ND |

| 53/M | Supraglottic | T4N2bM0 | - | - | TL+bilateral ND |

| 48/M | Transglottic | T4N0M0 | CB | Thyroid papillary carsinoma with neck metastasis | TL+bilateral ND+bilateral total thyroidectomy |

| 54/M | Supraglottic | T4N0M0 | HT | Pyriform sinus invasion+hypophrynx involvment | TL+bilateral ND+limited hypopharyngectmoty |

| 67/M | Supraglottic+glottic | T4N0M0 | CM | - | TL+bilateral ND |

| 65/M | Supraglottic+glottic | T3N1M0 | DI | Suracricoid partial laryngectomy+bilateral ND (7 days before) | TL |

| 54/M | Supraglottic+glottic | T3N0M0 | - | - | TL+bilateral ND |

| 58/M | Transglottic | T4N0M0 | - | - | TL+bilateral ND |

| 56/M | Glottic+subglottic | T4N2cM0 | - | TL+bilateral ND+bilateral thyroidectomy | |

| 71/M | Supraglottic | T 3N0M0 | HT+CB | - | TL+bilateral ND |

| 68/M | Supraglottic | T4N1M0 | CB | - | TL+bilateral ND |

| 61/M | Glottic+subglottic | T4N0M0 | - | - | TL+bilateral ND+bilateral thyroidectomy |

| 51/M | Supraglottic | T4N1M0 | CB | - | TL+bilateral ND |

| 66/M | Transglottic | T4N0M0 | DM+HT | - | TL+bilateral ND+bilateral thyroidectomy |

| 63/M | Glottic+subglottic | T4N0M0 | - | - | TL+bilateral ND+bilateral thyroidectomy |

| 51/M | Supraglottic+glottic | T4N1M0 | - | - | TL+bilateral ND |

| 64/M | Glottis+subglottic | T4N0M0 | - | - | TL+bilateral ND+bilateral thyroidectomy |

| 73/M | Supraglottic | T3N0M0 | - | TL+bilateral ND |

Table 2.

Rate of fistula in total laryngectomy after manual suture

| Source | No. of cases | Rate of fistula (%) | Year | Comparison with our study* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virtaniemi et al. [9] | 133 | 15 | 2001 | Not significant |

| Grau et al. [10] | 472 | 19 | 2003 | Significant |

| Smith et al. [11] | 223 | 55 | 2003 | Significant |

| Rubino et al. [12] | 155 | 55 | 2003 | Significant |

| Markou et al. [13] | 377 | 13 | 2004 | Not significant |

| Sarra et al. [14] | 30 | 34.5 | 2008 | Significant |

| Akduman et al. [8] | 53 | 35.9 | 2008 | Significant |

| White et al. [15] | 259 | 21 | 2012 | Significant |

| Sousa Ade et al. [16] | 93 | 15.1 | 2013 | Not significant |

| Aires et al. [17] | 94 | 21.3 | 2013 | Significant |

| Present study | 31 | 3.2 | 2015 |

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download