Abstract

Objectives

Rupture of the round window membrane with consecutive development of a perilymphatic fistula (PLF) is still a matter of controversial debate in the pathogenesis of idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSHL). Until now no consensus exists about whether these patients benefit from performing an exploratory tympanotomy with sealing of the round window. The aim of the present study was to analyze critically the effectiveness of sealing the round window membrane in patients with SSHL.

Methods

The clinical data of 51 patients with SSHL and a mean hearing decline of at least 60 dB over 5 frequencies who were treated with tympanotomy and sealing of the round window membrane were retrospectively analyzed. The results have been compared to the current state of the literature.

Results

Intraoperatively a round window membrane rupture or fluid leak was observed in none of the patients. After performing tympanotomy the mean improvement of hearing level was 32.7 dB. Twenty of 51 examined patients (39.2%) showed a mean improvement of the hearing level of more than 30 dB and a complete remission could be detected in 12 patients (23.5%). Reviewing the literature revealed no standard guidelines for definition or treatment of SSHL as well as for evaluation of hearing loss and its recovery.

Conclusion

The results of the present study and the literature should be discussed critically. It is unclear whether tympanotomy and sealing of the round window membrane may be a meaningful treatment for SSHL. Therefore this procedure should be discussed as a therapeutic option only in selected patients with sudden deafness or profound hearing loss in which PLF is strongly suspicious or conservative treatment failed.

Sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSHL) has been defined by the US National Institute for Deafness and Communication Disorders as a mostly unilateral decline of the hearing function of more than 30 dB in at least three sequential frequencies over 3 days or less [1]. SSHL was first described by De Kleyn [2] and was called sudden deafness by Hallberg [3] in 1956. Hearing loss may vary from mild to profound and approximately 10% of all patients with SSHL suffer from total hearing loss [4]. In Germany SSHL is not uncommon disease with an increasing incidence of SSHL of up to 160 cases in 100,000 people per year [5]. However, the pathogenesis of SSHL still remains unknown in most cases. Due to the mostly idiopathic character of the disease until now there is no generally accepted causal therapy regime.

In the case of profound SSHL without improvement after medical treatment the labyrinthine window rupture and the development of a perilymphatic fistula (PLF) should be considered as one possible etiologic factor [6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. According to the literature, exploratory tympanotomy with inspection and sealing of the labyrinthine window may be a therapeutic option in those patients [10,11,12]. However, there are no diagnostic tests for detecting a labyrinthine window rupture and clinical identification of a PLF is often difficult even at the time of surgery. The audiometric effect of sealing of the round window membrane has been of general interest since 20-30 years ago some surgeons performed this type of surgery in cases of SSHL. But due to the lack of evidence on a beneficial effect of the therapy, many surgeons now have reduced their activity in this surgical procedure for SSHL. Former studies about exploratory tympanotomy are usually characterized by a small number of patients, the lack of randomization, and inadequate statistical power.

For critical evaluation of possible role of tympanotomy on hearing outcome the present study retrospectively analyzed the audiometric results after performing tympanotomy and sealing of the round window membrane in patients with profound unilateral SSHL. In addition the influence of different clinical parameters on the hearing outcome was analyzed. The results have been critically compared to the current state of the literature.

We pursued a retrospective chart review of patients undergoing tympanotomy of the round window membrane for SSHL, between January 1, 2003, and June 30, 2010. Patients were included if they had suffered from unilateral SSHL with a mean decline in hearing of at least 60 dB over 5 frequencies (250, 500, 1,000, 2,000, and 4,000 Hz) which occurred within less than three days. All patients had a follow-up time of at least half a year. Exclusion criteria were bilateral SSHL or a follow-up of less than 6 months. Patients who had received other types of therapy before were also excluded. None of the patients had an acoustic trauma or barotrauma.

During the above mentioned time period a total of 1,290 patients with a unilateral SSHL were treated inpatient in our department. In 128 cases, the mean hearing loss was worse than 60 dB. In 30 out of 128 patients there was only medical treatment, e.g., with glucocorticoids or vasoactive drugs. In another 47 cases the follow-up was less than six months. The remaining 51 patients (32 males, 64%; 19 females, 34%) fulfilled the above mentioned inclusion criteria. The mean age at diagnosis was 62.8 years (range, 23 to 85 years). The present data refer to those 51 patients.

The patients were treated with 250 mg of prednisolon-21-hydrogensuccinat-natrium intravenously once daily on 3 following days with a subsequent reduction of the dose over 10 days orally. The treatment protocol further included 250-mL hydroxyethyl starch 6% intravenously twice a day for each three hours.

Indications for exploratory tympanotomy were acute hearing loss of at least 60 dB over 5 frequencies or sudden deafness with accompanying otologic symptoms like vertigo and no improvement or progression of hearing decline within the first days of systemic treatment. In most cases tympanotomy was performed under local anaesthesia by preparation of a tympanomeatal flap and using connective tissue for covering the round window area. The intraoperative evidence of PLF was evaluated.

The clinical findings were evaluated by descriptive analysis. These included age, gender, time between first symptoms, begin of therapy, the accompanying otologic symptoms like tinnitus, vertigo, feeling of ear fullness, and periaural dysaesthesia. Concerning recovery of accompanying otologic symptoms there was a quantitative classification by worsened, same, and improved findings or complete recovery.

The evaluation of the hearing recovery was performed in accordance to the Research Group on Sudden Deafness of the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare [13] as done in a former study [12]. Recovery was defined as an average hearing gain of at least 10 dB in five frequencies (250, 500, 1,000, 2,000, and 4,000 Hz). There was a quantitative classification by slight, marked, and complete recovery of hearing function. Complete recovery was defined as a hearing threshold within 0-20 dB in all frequencies or a recovery to the hearing level of the intact ear. Marked recovery was defined as a mean hearing gain of more than 30 dB in five frequencies, while slight recovery was a hearing gain of 10-30 dB (Table 1).

Student t-tests were used for detecting significant differences in the hearing gain, as well as the initial hearing loss between patients with or without accompanying otologic symptoms. To investigate the relationship between time period until the beginning of the treatment and hearing gain a linear univariate regression analysis with calculation of Pearson correlation coefficient was performed. For detection of significant differences of age, gender, accompanying symptoms, and time until begin of treatment between patients with complete versus no hearing recovery Fisher exact test and Student t-tests were used. In addition, a multivariate regression analysis was performed to investigate the impact of the mentioned clinical factors on the hearing gain. The results were considered as significant with a P-value of <0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS ver. 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

The mean hearing loss of 51 patients with unilateral SSHL was 73.3 dB. The left ear was affected in 25 cases (49%) and the right in 26 cases (51%). The mean time interval between onset of first symptoms and surgery was 5 days (range, 1 to 12 days) and tympanotomy was performed between one and eleven days after the beginning of medical therapy. 37 patients (72.5%) complained about tinnitus, 11 patients (21.6%) from vertigo, 3 patients (5.9%) had a feeling of ear fullness, and only one specified periauricular dysaesthesia (Table 2).

Intraoperatively signs of PLF could not be detected. Intraoperative complications occurred in 2 cases (3.9%). Each one of these patients suffered from an injury of the chorda tympani without evidence for residual symptoms in follow-up. No further intra- or postoperative complications occurred.

The average follow-up period after tympanotomy was 1.3 years (range, 0.5 to 5.7 years). After tympanotomy a mean hearing gain of 33.3 dB could be observed in 40 of the 51 examined patients (78.4%). A complete or marked recovery of the hearing function was observed in 12 (23.5%) and 20 of the patients (39.2%), respectively. A slight improvement of the hearing level was observed in 8 cases (15.7%) while 11 patients (21.6%) had no change of the hearing function (Table 3).

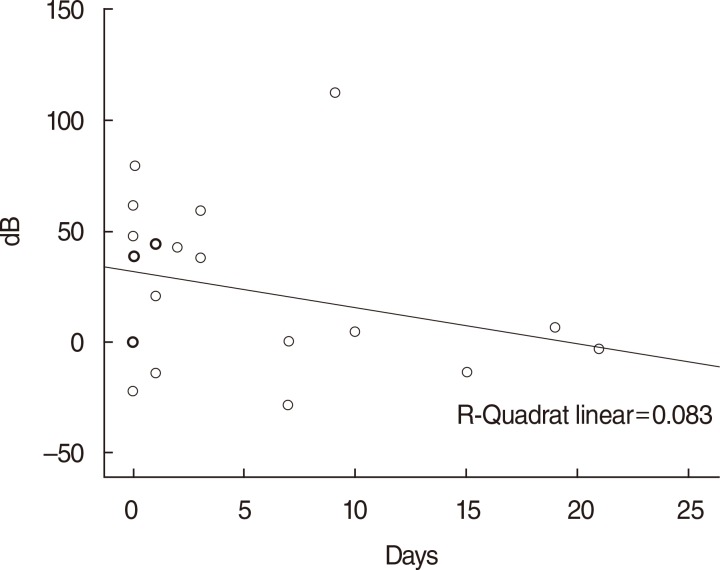

A partial or complete decrease of the associated symptoms could be observed in 72.8% (n=8) of the patients with vertigo, 54% (n=20) of the patients with tinnitus, and all patients (n=4) with a feeling of ear fullness or periauricular dysaethesia (Table 2). No significant association between the occurrence of accompanying symptoms and initial hearing loss could be observed. Patients with accompanying symptoms showed no significant differences in hearing gain. Multivariate regression analysis for age (P=0.566), sex (P=0.323), vertigo (P=0.638), tinnitus (P=0.633), feeling of ear fullness (P=0.717), and periaural dysaesthesia (P=0.843) revealed no significant relationship to the hearing outcome after surgery. Only the time period until the onset of therapy showed a marginally significant relationship with a worse hearing gain (P=0.057). In addition, the univariate regression analysis showed no significant correlation between the time period until the beginning of therapy and hearing recovery (Fig. 1). A comparison of patients with complete versus no recovery of the hearing threshold revealed also no significant difference in age, sex, initial hearing loss, vertigo, and tinnitus except for the time period between the occurrence of the first symptoms and the onset of therapy (Table 4). The mean time period between first symptoms and begin of therapy was 1.7 days for patients with complete hearing recovery and 7.9 days for patients without hearing recovery (P=0.024).

There is still controversial debate about different treatment strategies of SSHL and even the question arises whether to treat or not to treat SSHL. Spontaneous hearing improvement was examined by Mattox and Simmons [14] who compared corticosteroid-treated versus nontreated patients in a retrospective study. They found no significant difference in the hearing gain between treated or nontreated patients. A spontaneous recovery rate of 65% could be observed mostly within the first two weeks after the onset of symptoms. Other authors reported a spontaneous recovery rate up to 68% [15]. By reviewing published data, the spontaneous recovery rate was calculated up to 50% [16]. To estimate the effect of recovery of idiopathic SSHL under placebo and medical treatment recently a meta-analysis of prospective randomized placebo-controlled trials was performed [17]. The treatment effect of medical therapy was only slightly better than recovery under placebo with a mean hearing gain of 14.3 dB under placebo and 15.8 dB under active treatment. A significant effect of treatment could not be found. Compared to the spontaneous remission rate cited in literature the results of the present study revealed a marked or complete recovery rate of 62.7% in patients with a severe hearing loss (mean hearing loss, 73.3 dB). With a mean age at diagnosis of 62.8 years the present study group is comparatively old. In this context it has to be critically mentioned that the probable effect of a preexisting hearing defect on hearing outcome cannot be estimated because no hearing tests prior to SSHL could be evaluated.

Various therapeutic approaches for treatment of SSHL have been previously described in literature. Assuming vascular or inflammatory etiologic cause glucocorticoids, antioxidants, and vasoactive substances are frequently used as treatment approach. In cases of severe or profound hearing loss corticosteroids are supposed to achieve a hearing improvement [18].

As mentioned above PLF as one possible cause for SSHL is still a matter of controversial debate. Stroud and Calcaterra [19] first reported of spontaneous PLF in 1970 and until now there are only a few clinical trials about the incidence of PLF [20,21]. Performing an exploratory tympanotomy and sealing of the labyrinthine window is recommended in patients without response to systemic treatment as well as sudden deafness with suggestive symptoms like vertigo and might be associated with a better outcome than conservative treatment alone [12]. Neither the severity nor the pattern of hearing loss may predict a PLF [22]. Even a positive fistula test, a spontaneous nystagmus or a reduced vestibular response in caloric testing are not helpful for the diagnosis of PLF [23]. It is recommended to provide the indication for performing a tympanotomy by using various clinical, audiological, and vestibular findings [23]. However, the clinical diagnosis of PFL is nonreliable. Observation of fluid leak, direct inspection of round window rupture, and no simultaneous pressure transmission from the oval to the round window membrane are criteria to confirm the diagnosis of a PLF. However, according to the literature a fluid leak in the labyrinthine window recesses could be found in 40%-71% of patients with a PLF [7,8]. There is also a report that a large quantity of fluid leak could be found more often in patients, who were treated within the first week after the beginning of the symptoms [24]. In the same study patients with large quantity of fluid leak had a tendency toward a poor hearing recovery. Because of the necessity to drill the bony rim of the round window niche in order to visualize the round window membrane it has to be critically mentioned that the accumulation of clear fluid may be a result of the operation itself and this may lead to a false diagnosis of PFL. A round window membrane rupture or fluid leak could not be observed in the patients of the present study because the bony rim of the round window niche was not drilled.

It should be mentioned that an intermittent character of a PLF [21] may also explain the improvement in hearing threshold after treatment although no PLF can be observed at tympanotomy. Also the possible effect of inducing a hyperemia in the basal cochlea turn due to the insertion of dead connective tissue in the round window niche has also to be discussed in this context.

Although sealing of both oval and round window is recommended in patients in whom no fistula can be detected, some authors disagree this opinion. They observed that packing of autogenous tissue into the area of the ear windows may further dampen hearing [25]. In the present study only the round window area was packed with soft tissue. A surgery-related worsening of hearing function could not be found in the follow-up time.

Also, the time of performing tympanotomy is a matter of controversal debate. It is questionable, whether tympanotomy may be performed too early or too late. The rationale to treat a PLF with sealing of the round window membrane is to prevent further leakage of inner ear fluid. If so, then tympanotomy should be performed as early as possible. However, some authors do not recommend an early tympanotomy because a new trauma during surgery might decrease the chance of inner ear healing and spontaneous recovery may occur within 10 to 14 days anyway [6]. Therefore performing a tympanotomy after 10 days of conservative therapy or even later was advocated, if in the meantime no worsening of the symptoms occurs. In this context it has to be mentioned that delayed spontaneous recovery may appear even after 10 days of conservative treatment. We performed tympanotomy in all cases within 11 days of conservative treatment. So the recovery rate of our study may be overestimated by delayed spontaneous recovery rate. In addition, all patients received conservative treatment with cortison, which may have had an influence on the hearing outcome. In this context it is questionable, if performing delayed tympanotomy would have lead to worse audiometric results. Statistical analysis showed a nearly significant relationship between the time period until onset of therapy and a worse hearing gain. This does not mean that delayed tympanotomy has an influence on hearing gain, but any kind of delayed therapy seems to be associated with worse audiometric results.

Although the data of the present study show an improvement of hearing the results have to be critically evaluated. The present study has some limitations like the retrospective setting, the absence of a control-group and the combination of tympanotomy with systemic medical treatment in all cases. Furthermore there are no hearing tests prior to SSHL like other studies. Consequently a preexisting hearing deficit of the patients on the side of the SSHL cannot be excluded. These limitations are associated with a poor statistical power.

Although SSHL is a well-recognized condition the pathophysiology is still unknown in most cases. Neither a standard definition for SSHL nor a standard treatment protocol has been accepted until now. Furthermore there are no standard guidelines for evaluation of hearing loss and its recovery. In consequence until now the determination of any therapeutic benefit remains difficult and it is still unclear whether tympanotomy and sealing of the round window membrane may be a meaningful treatment for SSHL. Therefore this procedure should be discussed as a therapeutic option in selected patients with sudden deafness or profound hearing loss in which PLF is strongly suspicious or conservative treatment failed. A delayed beginning of therapy (conservative versus surgical) seems to be associated with a worse audiometric outcome. Accompanying symptoms do not seem to have a statistical significant influence on hearing gain.

References

1. National Institute of Health. Sudden deafness (NIH publication 00-4757). Bethesda (MD): National Institutes of Health;2000.

2. De Kleyn A. Sudden complete or partial loss of function of the octavus-system in apparently normal persons. Acta Otolaryngol. 1944; 1. 32(5-6):407–429.

3. Hallberg OE. Sudden deafness of obscure origin. Laryngoscope. 1956; 10. 66(10):1237–1267. PMID: 13377713.

4. Kanzaki J, Nomura Y. Incidence and prognosis of acute profound deafness in Japan. Auris Nasus Larynx. 1986; 13(2):71–77. PMID: 3813982.

5. Klemm E, Deutscher A, Msges R. A present investigation of the epidemiology in idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Laryngorhinootologie. 2009; 8. 88(8):524–527. PMID: 19194837.

6. Simmons FB. The double-membrane break syndrome in sudden hearing loss. Laryngoscope. 1979; 1. 89(1):59–66. PMID: 423653.

7. Goodhill V, Brockman SJ, Harris I, Hantz O. Sudden deafness and labyrinthine window ruptures. Audio-vestibular observations. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1973; Jan-Feb. 82(1):2–12. PMID: 4685566.

8. Kanzaki J. Idiopathic sudden progressive hearing loss and round window membrane rupture. Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1986; 243(3):158–161. PMID: 3753291.

9. Mertens J, Rudert H. Sudden deafness caused by rupture of the round window membrane. Surgical indications, course and prognosis. HNO. 1986; 8. 34(8):320–324. PMID: 2428778.

10. Tigges G, Stoll W, Schmal F. Prognostic factors in hearing recovery following sudden unilateral deafness. HNO. 2003; 4. 51(4):305–309. PMID: 12682732.

11. Maier W, Fradis M, Kimpel S, Schipper J, Laszig R. Results of exploratory tympanotomy following sudden unilateral deafness and its effects on hearing restoration. Ear Nose Throat J. 2008; 8. 87(8):438–451. PMID: 18712692.

12. Gedlicka C, Formanek M, Ehrenberger K. Analysis of 60 patients after tympanotomy and sealing of the round window membrane after acute unilateral sensorineural hearing loss. Am J Otolaryngol. 2009; May-Jun. 30(3):157–161. PMID: 19410119.

14. Mattox DE, Simmons FB. Natural history of sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1977; Jul-Aug. 86(4 Pt 1):463–480. PMID: 889223.

15. Weinaug P. Spontaneous remission in sudden deafness. HNO. 1984; 8. 32(8):346–351. PMID: 6480433.

16. Heiden C, Porzsolt F, Biesinger E, Hoing R. Spontaneous remission of sudden deafness. HNO. 2000; 8. 48(8):621–623. PMID: 10994175.

17. Labus J, Breil J, Stutzer H, Michel O. Meta-analysis for the effect of medical therapy vs. placebo on recovery of idiopathic sudden hearing loss. Laryngoscope. 2010; 9. 120(9):1863–1871. PMID: 20803741.

18. Veldman JE, Hanada T, Meeuwsen F. Diagnostic and therapeutic dilemmas in rapidly progressive sensorineural hearing loss and sudden deafness. A reappraisal of immune reactivity in inner ear disorders. Acta Otolaryngol. 1993; 5. 113(3):303–306. PMID: 7685975.

19. Stroud MH, Calcaterra TC. Spontaneous perilymph fistulas. Laryngoscope. 1970; 3. 80(3):479–487. PMID: 5436969.

20. House JW, Morris MS, Kramer SJ, Shasky GL, Coggan BB, Putter JS. Perilymphatic fistula: surgical experience in the United States. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991; 7. 105(1):51–61. PMID: 1909008.

21. Shelton C, Simmons FB. Perilymph fistula: the Stanford experience. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1988; Mar-Apr. 97(2 Pt 1):105–108. PMID: 3258485.

22. Muntarbhorn K, Webber PA. Labyrinthine window rupture with round window predominance: a long-term review of 32 cases. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1987; 4. 12(2):103–108. PMID: 3581487.

23. Vartiainen E, Nuutinen J, Karjalainen S, Nykanen K. Perilymph fistula: a diagnostic dilemma. J Laryngol Otol. 1991; 4. 105(4):270–273. PMID: 2026938.

24. Nagai T, Nagai M. Labyrinthine window rupture as a cause of acute sensorineural hearing loss. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012; 1. 269(1):67–71. PMID: 21448612.

25. Pappas DG, Schneiderman TS. Perilymphatic fistula in pediatric patients with a preexisting sensorineural loss. Am J Otol. 1989; 11. 10(6):499–501. PMID: 2610244.

Fig. 1

Linear univariate regression analysis of duration before initial presentation and influence on the hearing gain in 51 patients with unilateral sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Hearing gain (dB), duration before initial presentation (day). Pearson correlation R=-0.23; P=0.057.

Table 1.

Evaluation of hearing recovery according to the Research Group on sudden deafness of the Ministry of Health and Welfare

Modified from Kanzaki [13].

Table 2.

Clinical results with respect to accompanying otologic symptoms

Table 3.

Audiometric results after treatment of 51 patients with unilateral sudden sensorineural hearing loss

| Hearing gain | No. (%) | Mean hearing gain (dB) |

|---|---|---|

| Complete recovery | 12 (23.5) | 52.33 |

| Marked recovery | 20 (39.2) | 48.83 |

| Slight recovery | 8 (15.7) | 20.43 |

| No change | 11 (21.6) | –6.50 |

Table 4.

Clinical differences between patients with complete versus no recovery of hearing function

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download