Abstract

Objectives

Premedication with clonidine has been found to reduce the bleeding during endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS), therefore lowering the risk of surgical complications. Premedication is an essential part of pre-surgical care and can potentially affect magnitude of systemic stress response to a surgical procedure. The aim of this study was to compare the efficacy of premedication with clonidine and midazolam in patients undergoing sinus surgery.

Methods

Forty-four patients undergoing ESS for chronic sinusitis and polyp removal were enrolled and randomly assigned to receive either oral clonidine or midazolam as a premedication before receiving propofol/remifentanil total intravenous anesthesia. The effect of this premedication choice on anesthetic requirements, intraoperative hemodynamic profile, preoperative anxiety and sedation as well as postoperative pain and shivering were examined in each premedication group.

Results

Total intraoperative remifentanil requirement was lower in the clonidine group as compared to the midazolam group 503.2±147.0 µg vs. 784.5±283.8 µg, respectively (P<0.001). There was no difference between groups in required induction dose of propofol, level of preoperative anxiety, level of sedation and postoperative shivering. Intraoperative systemic blood pressure and heart rate response had a more favorable profile in patients premedicated with clonidine. Postoperative pain assessed by visual analogue scale for pain was lower in the clonidine group compared with to the midazolam premedication group.

Interest in finding alternatives and major innovation in surgical technology has led to improvements in anesthesia and perioperative care with documented benefits on early and late postoperative outcomes. Since endoscopic surgical techniques have been developed, proper anesthetic management should be tailored for optimal visualization of the surgical field, controlling intraoperative hemodynamic, homeostasis and hemostasis [1].

Premedication with clonidine reduce bleeding during endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) and therefore lowers the risk of surgical complications mostly due to its known benefit related to reduction in nasal mucosa blood flow [2,3]. Also, in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery, clonidine used as a premedication agent was reported to reduce the risk of cardiac mortality [4] and to have an anesthetic sparing effect [5,6,7].

The present study was design to test the hypothesis that premedication with clonidine can provide clinically relevant benefits. We therefore compared the effect of clonidine and conventional premedication with midazolam on intraoperative anesthetic requirements, hemodynamic profile, level of preoperative anxiety and sedation as well as postoperative pain and shivering in patients undergoing ESS.

After obtaining approval from the local Institutional Review Board (Bioethics Committee of the Nicolaus Copernicus University) and informed consent from each participant, 44 patients with an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status I or II were included in this trial. All patients had the same indications for ESS and comparable advancement of polyps in the nasal cavities as assessed by preoperative computed tomography (CT) of the paranasal sinuses (graded on Lund-Mackay scale) [8].

Exclusion criteria included significant heart disease, epilepsy, perceptive hearing loss, body weight less than 50 kg and over 100 kg, pregnancy, and preoperative anxiety score (visual analogue scale for anxiety, VAS-A) above 5. Also, patients receiving clonidine or benzodiazepines, neuroleptics or antidepressants two weeks prior to the study were excluded.

Patients were randomized (simple random sampling) to receive oral premedication consisting of clonidine (Iporel, WZF Polfa, Warsaw, Poland) at a dose of approximately 3 µg/kg body weight or midazolam at a dose of approximately 0.1 mg/kg body weight (Dormicum, Roche, Bache, Switzerland) 60 minutes before induction of general anesthesia.

Prior to administration of premedication anxiety level was evaluated using VAS-A 1. After transfer to the operating room but before induction of general anesthesia anxiety and sedation were assessed using VAS-A 2 and Ramsay sedation score (RSS), respectively.

Standard ASA noninvasive monitoring [9] was supplemented with A-line autoregressive index (AAI) in all patients (AEP/2 monitor; Danmeter, Odense C, Denmark); with numerical value between 0 and 60 (0 indicating very deep hypnosis and 60 indicating awake state). All patients received the same induction consisting of propofol (Plofed 1%; Polfa Warszawa S.A., Warsaw, Poland) delivered in divided doses of 20 mg every 20 seconds, supplemented with fentanyl 2 µg/kg (Fentanyl, WZF Polfa) titrated to achieve AAI index of 15-25 and clinical signs of unconsciousness as assessed by observer's assessment of alertness/sedation scale (OASS). After loss of consciousness, muscle relaxant, vecuronium (Norcuron, Organon, Holland) at a dose of 0.1 mg/kg was administered to facilitate endotracheal intubation. General anesthesia was maintained with infusion of propofol/remifentanil total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA). Mechanical ventilation was provided with a mixture of oxygen and air to maintain FiO2 0.4-0.5 and end-tidal carbon dioxide concentration at 35-38 mmHg.

TIVA was maintained with continuous infusion of remifentanil to obtain predicted serum concentration in the range of 1.5-6.0 ng/mL (Minto model), titrated to the hemodynamic parameters (heart rate [HR] between 60-90 bpm and mean blood pressure between 60-95 mmHg), if the incremental increase of remifentanil infusion rate was not sufficient to decrease mean arterial pressure (MAP) below 95 mmHg, bolus dose (10 mg) of urapidil (Ebrantil, Byk Gulden Lomberg, Konstanz, Germany) was administered intravenously.

Propofol infusion was targeted to obtain a predicted serum concentration of 3.0 µg/mL (Schneider model). The infusion of propofol and remifentanil were stopped at the conclusion of the surgical procedure followed by intravenous administration of acetaminophen (Perfalgan, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Uxbridge, UK) at a dose of 1 g. Both groups received the same amount of intravenous fluids: 0.9% NaCl solution at a rate of 5 mL/kg/hour.

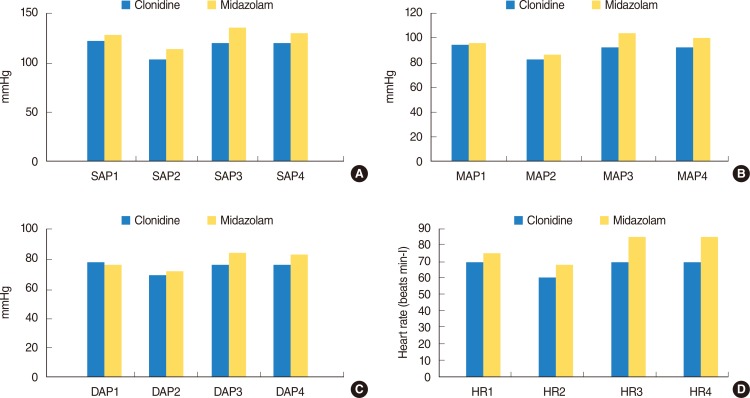

The propofol dose used during induction of anesthesia, the application rates and cumulative dose of remifentanil used during the entire case were recorded. Hemodynamic parameters including systolic blood pressure (SAP), diastolic blood pressure (DAP), mean arterial pressure (MAP), and HR were recorded upon admission to the operating room (SAP1, DAP1, MAP1, HR1), after induction of anesthesia (SAP2, DAP2, MAP2, HR2) during endotracheal intubation (SAP3, DAP3, MAP3, HR3) and extubation (SAP4, DAP4, MAP4, HR4). In the recovery room, pain and shivering were assessed using the visual analogue scale for pain (VAS-P) and the 5-point scale of Wrench respectively [10].

Mann-Whitney U-test, Student t-test, χ2-test, the Fisher exact test were used as appropriate to compare premedication groups with respect to baseline characteristic and outcomes of interest; significance level was set at 0.05, Statistica ver. 8.0 (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, USA) was used to perform the analysis.

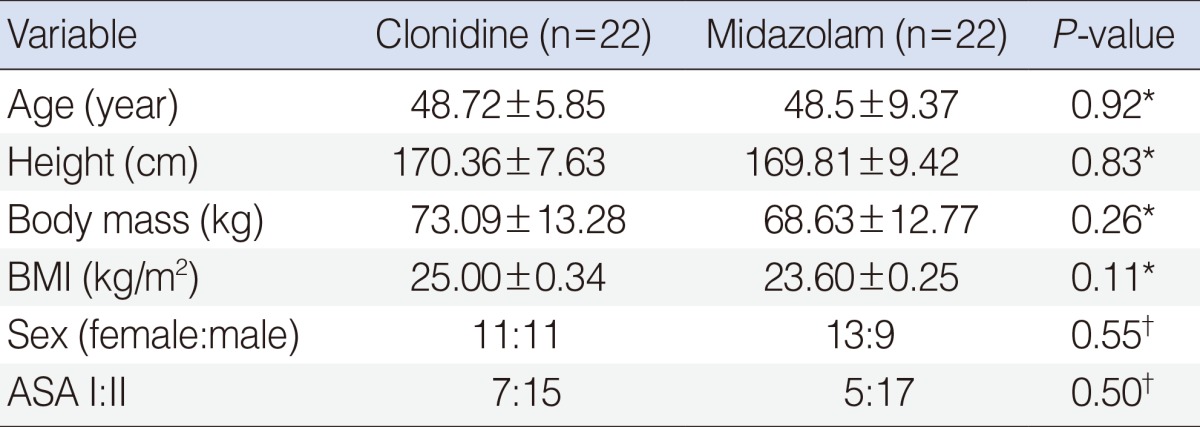

Baseline characteristics of patients in clonidine and midazolam premedication groups were similar (Table 1).

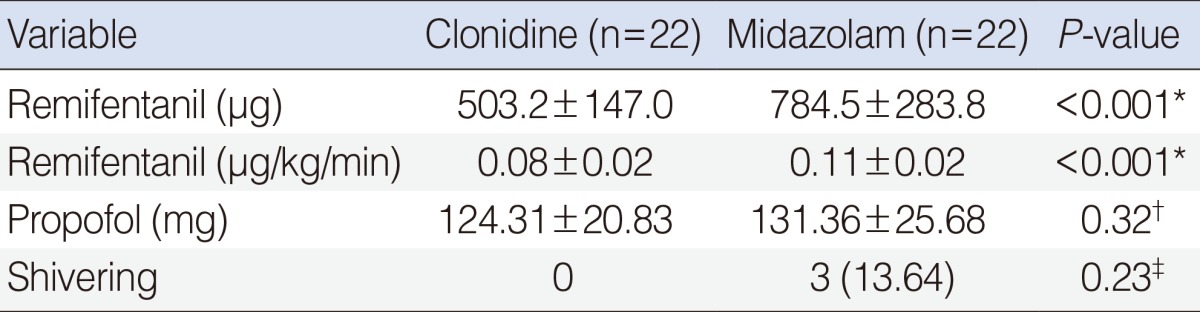

The total induction dose of propofol, was similar in both groups (124.3±20.8 mg vs. 131.3±25.7 mg; P=0.32) (Table 2). However, the total remifentanil requirement during the entire procedure was lower in the clonidine group (503.2±147.0 µg vs. 784.5±283.8 µg; P<0.001) as well as application rates (0.08±0.02 µg/kg/minute vs. 0.11±0.02 µg/kg/minute; P<0.001) (Table 2).

SAP was lower in the clonidine group after induction of anesthesia, during endotracheal intubation and extubation (P=0.02, P<0.001, P=0.01), as compared to the midazolam group (Fig. 1A). Mean blood pressure was lower in clonidine group during endotracheal intubation and extubation (P<0.001, P=0.009, respectively) (Fig. 1B). DAP was lower in clonidine premedication group during endotracheal intubation and extubation as compared with patients in the midazolam premedication group (P=0.001, P=0.021, respectively) (Fig. 1C). HR in the clonidine group was lower after induction of anesthesia, during endotracheal intubation and extubation as compared with patients after midazolam premedication (P=0.002, P<0.001, P<0.001, respectively) (Fig. 1D).

There was no difference between the groups in the level of sedation and anxiety scores (Table 3) as well as incidence of postoperative shivering (P=0.16, P=0.64, P=0.31, P=0.23, respectively) (Table 2). Postoperative pain scores measured using the VAS-P scale were lower in clonidine group (P=0.05) (Table 3).

Our investigation demonstrated that premedication with clonidine, as compared to standard midazolam premedication, can provide clinically relevant benefits: reduction of intraoperative requirement for remifentanil, better postoperative pain control and smoother intraoperative hemodynamic profile.

Alpha-2 agonists have been shown to have beneficial analgesic, sedative [6,11,12] and opioid sparing effects [13]. In animal studies clonidine and dexmedetomidine were reported to reduce the minimal alveolar concentration for halothane by nearly 50% and 90%, respectively [14,15]. The anesthetic and analgesic sparing effects is most likely related to the direct action on alpha-2 adrenergic receptors in the central nervous system [16,17] and is evident for volatile and intravenous anesthetics. Ghignone et al. [5] showed a 45% reduction in requirements for analgesics during the intraoperative period after clonidine premedication compared to standard premedication in patients undergoing bypass surgery. Flacke et al. [18] demonstrated reduced sufentanil requirement by 40% while improving hemodynamic profile during coronary artery bypass graft as well. Interestingly Frank et al. [19], similarly to our investigation, demonstrated a reduction in cumulative remifentanil dose by 24% after clonidine premedication in patients undergoing maxillofacial surgery under TIVA.

In contrast to other studies, we were unable to demonstrate reduction in propofol dose required for induction of general anesthesia [20,21]. That could be related to the differences in monitoring of unconsciousness amongst the studies: we used auditory evoked potential-guided propofol dosing while others used hemodynamic parameters or processed electroencephalography to determine state of unconsciousness during induction [20,21,22].

Clonidine administration in perioperative settings is safe and serious complications are very rare. In clinically relevant doses, preoperative use of clonidine is not associated with a risk of respiratory depression, which may be of particular importance in patients undergoing procedures on upper airways [6]. Also because clonidine stimulates not only the alpha 2 receptor but alpha 1 receptors as well, it does not inhibit the baroreceptor reflex, but only reduces its sensitivity, which prevents the significant decrease in blood pressure [6]. This is of particular importance in same day surgery patients as postoperative hypotension may delay discharge.

Our results confirmed the beneficial effect of clonidine on attenuation of hemodynamic response associated with laryngoscopy and endotracheal intubation [23]. As previously described, hypertension, tachycardia and in some cases cardiac arrhythmias are driven by sudden increase of plasma adrenaline and noradrenaline concentration in response to the manipulation of the airways [24,25,26]. Interestingly 5 patients in the midazolam group (vs. none in clonidine group) required administration of an additional agent (urapidil) to treat intraoperative hypertension, this suggests that premedication with clonidine provides much better control of the hemodynamic response to the stress of surgery intraoperatively.

Consistently with other studies we did not demonstrate any difference in degree of anxiolysis [19] or the level of sedation based on RSS [27] provided by premedication doses of clonidine and midazolam.

Postoperative pain was lower in patients who received clonidine premedication. This finding is in agreement with previous studies showing that patients undergoing abdominal hysterectomy treated with clonidine reported less pain in the postoperative period [28].

Postoperative shivering may complicate postoperative recovery after general anesthesia in as many as 5%-65% of patients [1]. Clonidine has been demonstrated to reduce the incidence of shivering significantly, however in our study we were not able to confirm that. This could be related to the fact that five patients in the midazolam premedication group received intraoperatively urapidil (to control hypertension), which by itself reduces shivering.

One of the limitations of this study is that we evaluated the effect of clonidine premedication in ASA I and II patients only, excluding patients with significant comorbidities. However presented results may be considered a pilot for the future investigation evaluating outcomes in patients with advanced coexisting diseases undergoing sinus surgery for whom, better hemodynamic profile provided by clonidine premedication may be more important. Based on the results of this investigation premedication with clonidine may be an attractive alternative for standard midazolam premedication before ESS.

In conclusion, premedication with clonidine provides better attenuation of hemodynamic responses and reduction of intraoperative remifentanil requirements in patients undergoing ESS. Postoperative pain seems to be better controlled after clonidine premedication as well.

References

1. Abdelmalak B, Doyle DJ. Anesthesia for endoscopic sinus surgery. In : Abdelmalak B, Doyle DJ, editors. Anesthesia for otolaryngologic surgery. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press;2013. p. 121–132.

2. Mohseni M, Ebneshahidi A. The effect of oral clonidine premedication on blood loss and the quality of the surgical field during endoscopic sinus surgery: a placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Anesth. 2011; 8. 25(4):614–617. PMID: 21590473.

3. Wawrzyniak K, Kusza K, Cywinski JB, Burduk PK, Kazmierczak W. Premedication with clonidine before TIVA optimizes surgical field visualization and shortens duration of endoscopic sinus surgery: results of a clinical trial. Rhinology. 2013; 9. 51(3):259–264. PMID: 23943734.

4. Wallace AW. Clonidine and modification of perioperative outcome. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2006; 8. 19(4):411–417. PMID: 16829723.

5. Ghignone M, Quintin L, Duke PC, Kehler CH, Calvillo O. Effects of clonidine on narcotic requirements and hemodynamic response during induction of fentanyl anesthesia and endotracheal intubation. Anesthesiology. 1986; 1. 64(1):36–42. PMID: 3942335.

6. Maze M, Tranquilli W. Alpha-2 adrenoceptor agonist: defining the role in clinical anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1991; 3. 74(3):581–605. PMID: 1672060.

7. Morris J, Acheson M, Reeves M, Myles PS. Effect of clonidine pre-medication on propofol requirements during lower extremity vascular surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Anaesth. 2005; 8. 95(2):183–188. PMID: 15951325.

8. Lund VJ, Mackay IS. Staging in rhinosinusitis. Rhinology. 1993; 12. 31(4):183–184. PMID: 8140385.

9. American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) [Internet]. Schaumburg, IL: ASA;c1995-2014. cited 2014 Aug 12. Available from: http://www.asahq.org.

10. Wrench IJ, Cavill G, Ward JE, Crossley AW. Comparison between alfentanil, pethidine and placebo in the treatment of post-anaesthetic shivering. Br J Anaesth. 1997; 10. 79(4):541–542. PMID: 9389278.

11. Hall JE, Uhrich TD, Ebert TJ. Sedative, analgesic and cognitive effects of clonidine infusions in humans. Br J Anaesth. 2001; 1. 86(1):5–11. PMID: 11575409.

12. Hall D, Rezvan E, Tatakis D, Walters JD. Oral clonidine pretreatment prior to venous cannulation. Anesth Prog. 2006; Summer. 53(2):34–42. PMID: 16863391.

13. Laisalmi M, Koivusalo AM, Valta P, Tikkanen I, Lindgren L. Clonidine provides opioid-sparing effect, stable hemodynamics, and renal integrity during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2001; 11. 15(11):1331–1335. PMID: 11727145.

14. Segal IS, Vickery RG, Walton JK, Doze VA, Maze M. Dexmedetomidine diminishes halothane anesthetic requirements in rats through a postsynaptic alpha 2 adrenergic receptor. Anesthesiology. 1988; 12. 69(6):818–823. PMID: 2848424.

15. Bloor BC, Flacke WE. Reduction in halothane anesthetic requirement by clonidine, an alpha-adrenergic agonist. Anesth Analg. 1982; 9. 61(9):741–745. PMID: 6125112.

16. Correa-Sales C, Rabin BC, Maze MA. A hypnotic response to dexmedetomidine, an alpha-2 agonist, is mediated in the locus coeruleus in rats. Anesthesiology. 1992; 6. 76(6):948–952. PMID: 1350889.

17. Jaakola ML, Salonen M, Lehtinen R, Scheinin H. The analgesic action of dexmedetomidine-a novel alpha 2-adrenoceptor agonist-in healthy volunteers. Pain. 1991; 9. 46(3):281–285. PMID: 1684653.

18. Flacke JW, Bloor BC, Flacke WE, Wong D, Dazza S, Stead SW, et al. Reduced narcotic requirement by clonidine with improved hemodynamic and adrenergic stability in patients undergoing coronary bypass surgery. Anesthesiology. 1987; 7. 67(1):11–19. PMID: 3496811.

19. Frank T, Thieme V, Radow L. Premedication in maxillofacial surgery under total intravenous anesthesia. Effects of clonidine compared to midazolam on the perioperative course. Anasthesiol Intensivmed Notfallmed Schmerzther. 2000; 7. 35(7):428–434. PMID: 10949680.

20. Goyagi T, Tanaka M, Nishikawa T. Oral clonidine premedication reduces induction dose and prolongs awakening time from propofol-nitrous oxide anesthesia. Can J Anaesth. 1999; 9. 46(9):894–896. PMID: 10490161.

21. Fehr SB, Zalunardo MP, Seifert B, Rentsch KM, Rohling RG, Pasch T, et al. Clonidine decreases propofol requirements during anaesthesia: effect on bispectral index. Br J Anaesth. 2001; 5. 86(5):627–632. PMID: 11575336.

22. Imai Y, Mammoto T, Murakami K, Kita T, Sakai T, Kagawa K, et al. The effects of preanesthetic oral clonidine on total requirement of propofol for general anesthesia. J Clin Anesth. 1998; 12. 10(8):660–665. PMID: 9873968.

23. Matot I, Sichel JY, Yofe V, Gozal Y. The effect of clonidine premedication on hemodynamic responses to microlaryngoscopy and rigid bronchoscopy. Anesth Analg. 2000; 10. 91(4):828–833. PMID: 11004033.

24. Kulka PJ, Tryba M, Zenz M. Dose-response effects of intravenous clonidine on stress response during induction of anesthesia in coronary artery bypass graft patients. Anesth Analg. 1995; 2. 80(2):263–268. PMID: 7818111.

25. Aho M, Lehtinen AM, Laatikainen T, Korttila K. Effects of intramuscular clonidine on hemodynamic and plasma beta-endorphin responses to gynecologic laparoscopy. Anesthesiology. 1990; 5. 72(5):797–802. PMID: 2140250.

26. Costello TG, Cormack JR. Clonidine premedication decreases hemodynamic responses to pin head-holder application during craniotomy. Anesth Analg. 1998; 5. 86(5):1001–1004. PMID: 9585285.

27. Paris A, Kaufmann M, Tonner PH, Renz P, Lemke T, Ledowski T, et al. Effects of clonidine and midazolam premedication on bispectral index and recovery after elective surgery. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2009; 7. 26(7):603–610. PMID: 19367170.

28. Hidalgo MP, Auzani JA, Rumpel LC, Moreira NL Jr, Cursino AW, Caumo W. The clinical effect of small oral clonidine doses on perioperative outcomes in patients undergoing abdominal hysterectomy. Anesth Analg. 2005; 3. 100(3):795–802. PMID: 15728070.

Fig. 1

Comparison of premedication choice (clonidine vs. midazolam) on hemodynamic parameters during procedure. Heart rate (HR), systolic blood pressure (SAP), diastolic blood pressure (DAP), mean arterial pressure (MAP) in admission to the operating room (SAP1, DAP1, MAP1, HR1), after induction of anesthesia (SAP2, DAP2, MAP2, HR2) during endotracheal intubation (SAP3, DAP3, MAP3, HR3) and extubation (SAP4, DAP4, MAP4, HR4).

Table 1

Comparison of perioperative characteristic between clonidine and midazolam premedication groups

Table 2

Comparison of premedication choice (clonidine vs. midazolam) on anesthetic requirement and postoperative shivering

Table 3

Comparison of premedication choice (clonidine vs. midazolam)

Values are presented as median (min-max).

RSS, Ramsay sedation score; VAS-A, visual analogue scale for anxiety; VAS-P, visual analogue scale for pain.

*Mann-Whitney U-test. †Anxiety level prior to administration of premedication. ‡Anxiety level after transfer to the operating room but before induction of general anesthesia.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download