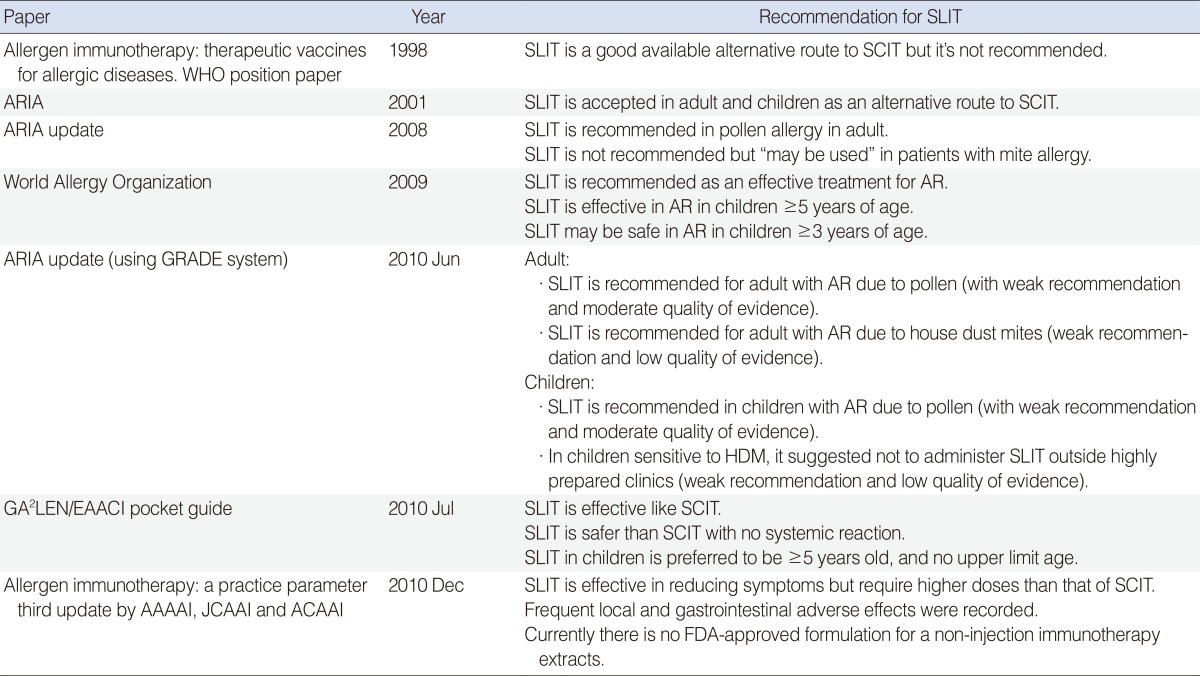

1. Bousquet J, Lockey R, Malling HJ. Allergen immunotherapy: therapeutic vaccines for allergic diseases. A WHO position paper. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998; 10. 102(4 Pt 1):558–562. PMID:

9802362.

2. Reed SD, Lee TA, McCrory DC. The economic burden of allergic rhinitis: a critical evaluation of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics. 2004; 22(6):345–361. PMID:

15099121.

3. Radulovic S, Calderon MA, Wilson D, Durham S. Sublingual immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010; 12. (12):CD002893. PMID:

21154351.

4. Scadding GK, Brostoff J. Low dose sublingual therapy in patients with allergic rhinitis due to house dust mite. Clin Allergy. 1986; 9. 16(5):483–491. PMID:

3536171.

5. Noon L. Prophylactic inoculation against hay fever. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1953; 4(4):285–288. PMID:

13096152.

6. Canonica GW, Passalacqua G. Sublingual immunotherapy in the treatment of adult allergic rhinitis patients. Allergy. 2006; 7. 61(Suppl 81):20–23. PMID:

16792602.

7. Brozek JL, Bousquet J, Baena-Cagnani CE, Bonini S, Canonica GW, Casale TB, et al. Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) guidelines: 2010 revision. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010; 9. 126(3):466–476. PMID:

20816182.

8. Bousquet J, Khaltaev N, Cruz AA, Denburg J, Fokkens WJ, Togias A, et al. Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) 2008 update (in collaboration with the World Health Organization, GA2LEN and AllerGen). Allergy. 2008; 4. 63(Suppl 86):8–160. PMID:

18331513.

9. Kawauchi H, Goda K, Tongu M, Yamada T, Aoi N, Morikura I, et al. Short review on sublingual immunotherapy for patients with allergic rhinitis: from bench to bedside. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 2011; 72:103–106. PMID:

21865703.

10. Bahceciler NN, Arikan C, Taylor A, Akdis M, Blaser K, Barlan IB, et al. Impact of sublingual immunotherapy on specific antibody levels in asthmatic children allergic to house dust mites. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2005; 3. 136(3):287–294. PMID:

15722639.

11. Incorvaia C, Di Rienzo A, Celani C, Makri E, Frati F. Treating allergic rhinitis by sublingual immunotherapy: a review. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2012; 48(2):172–176. PMID:

22751560.

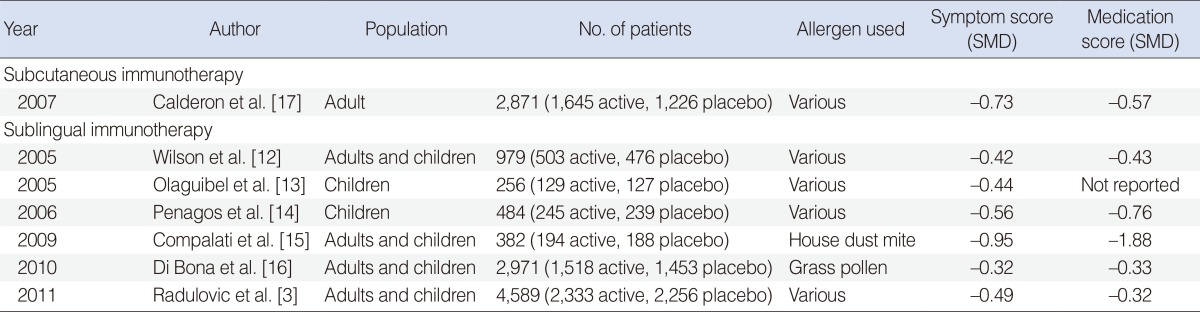

12. Wilson DR, Lima MT, Durham SR. Sublingual immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy. 2005; 1. 60(1):4–12. PMID:

15575924.

13. Olaguibel JM, Alvarez Puebla MJ. Efficacy of sublingual allergen vaccination for respiratory allergy in children. Conclusions from one meta-analysis. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2005; 15(1):9–16.

14. Penagos M, Compalati E, Tarantini F, Baena-Cagnani R, Huerta J, Passalacqua G, et al. Efficacy of sublingual immunotherapy in the treatment of allergic rhinitis in pediatric patients 3 to 18 years of age: a meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trials. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006; 8. 97(2):141–148. PMID:

16937742.

15. Compalati E, Passalacqua G, Bonini M, Canonica GW. The efficacy of sublingual immunotherapy for house dust mites respiratory allergy: results of a GA2LEN meta-analysis. Allergy. 2009; 11. 64(11):1570–1579. PMID:

19796205.

16. Di Bona D, Plaia A, Scafidi V, Leto-Barone MS, Di Lorenzo G. Efficacy of sublingual immunotherapy with grass allergens for seasonal allergic rhinitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010; 9. 126(3):558–566. PMID:

20674964.

17. Calderon MA, Alves B, Jacobson M, Hurwitz B, Sheikh A, Durham S. Allergen injection immunotherapy for seasonal allergic rhinitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007; 1. (1):CD001936. PMID:

17253469.

18. Egger M, Smith GD, Phillips AN. Meta-analysis: principles and procedures. BMJ. 1997; 12. 315(7121):1533–1537. PMID:

9432252.

19. Shekelle PG, Woolf SH, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Clinical guidelines: developing guidelines. BMJ. 1999; 2. 318(7183):593–596. PMID:

10037645.

20. Nieto A, Mazon A, Pamies R, Bruno L, Navarro M, Montanes A. Sublingual immunotherapy for allergic respiratory diseases: an evaluation of meta-analyses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009; 7. 124(1):157–161. PMID:

19500824.

21. Viswanathan RK, Busse WW. Allergen immunotherapy in allergic respiratory diseases: from mechanisms to meta-analyses. Chest. 2012; 5. 141(5):1303–1314. PMID:

22553263.

22. Marogna M, Spadolini I, Massolo A, Zanon P, Berra D, Chiodini E, et al. Effects of sublingual immunotherapy for multiple or single allergens in polysensitized patients. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007; 3. 98(3):274–280. PMID:

17378260.

23. Amar SM, Harbeck RJ, Sills M, Silveira LJ, O'Brien H, Nelson HS. Response to sublingual immunotherapy with grass pollen extract: monotherapy versus combination in a multiallergen extract. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009; 7. 124(1):150–156. PMID:

19523672.

24. Keles S, Karakoc-Aydiner E, Ozen A, Izgi AG, Tevetoglu A, Akkoc T, et al. A novel approach in allergen-specific immunotherapy: combination of sublingual and subcutaneous routes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011; 10. 128(4):808–815. PMID:

21641635.

25. Bahceciler NN, Galip N, Cobanoglu N. Multiallergen-specific immunotherapy in polysensitized patients: where are we? Immunotherapy. 2013; 2. 5(2):183–190. PMID:

23413909.

26. Canonica GW, Bousquet J, Casale T, Lockey RF, Baena-Cagnani CE, Pawankar R, et al. Sub-lingual immunotherapy: World Allergy Organization Position Paper 2009. Allergy. 2009; 12. 64(Suppl 91):1–59. PMID:

20041860.

27. Passalacqua G. Specific immunotherapy: beyond the clinical scores. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2011; 11. 107(5):401–406. PMID:

22018610.

28. Tahamiler R, Saritzali G, Canakcioglu S. Long-term efficacy of sublingual immunotherapy in patients with perennial rhinitis. Laryngoscope. 2007; 6. 117(6):965–969. PMID:

17545861.

29. Marogna M, Spadolini I, Massolo A, Canonica GW, Passalacqua G. Long-lasting effects of sublingual immunotherapy according to its duration: a 15-year prospective study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010; 11. 126(5):969–975. PMID:

20934206.

30. Marogna M, Tomassetti D, Bernasconi A, Colombo F, Massolo A, Businco AD, et al. Preventive effects of sublingual immunotherapy in childhood: an open randomized controlled study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008; 8. 101(2):206–211. PMID:

18727478.

31. Calderon MA, Casale TB, Togias A, Bousquet J, Durham SR, Demoly P. Allergen-specific immunotherapy for respiratory allergies: from meta-analysis to registration and beyond. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011; 1. 127(1):30–38. PMID:

20965551.

32. Antico A, Pagani M, Crema A. Anaphylaxis by latex sublingual immunotherapy. Allergy. 2006; 10. 61(10):1236–1237. PMID:

16942577.

33. Blazowski L. Anaphylactic shock because of sublingual immunotherapy overdose during third year of maintenance dose. Allergy. 2008; 3. 63(3):374. PMID:

18076729.

34. de Groot H, Bijl A. Anaphylactic reaction after the first dose of sublingual immunotherapy with grass pollen tablet. Allergy. 2009; 6. 64(6):963–964. PMID:

19222420.

35. Dunsky EH, Goldstein MF, Dvorin DJ, Belecanech GA. Anaphylaxis to sublingual immunotherapy. Allergy. 2006; 10. 61(10):1235. PMID:

16942576.

36. Eifan AO, Keles S, Bahceciler NN, Barlan IB. Anaphylaxis to multiple pollen allergen sublingual immunotherapy. Allergy. 2007; 5. 62(5):567–568. PMID:

17313400.

37. Calderón MA, Simons FE, Malling HJ, Lockey RF, Moingeon P, Demoly P. Sublingual allergen immunotherapy: mode of action and its relationship with the safety profile. Allergy. 2012; 3. 67(3):302–311. PMID:

22150126.

38. Fiocchi A, Pajno G, La Grutta S, Pezzuto F, Incorvaia C, Sensi L, et al. Safety of sublingual-swallow immunotherapy in children aged 3 to 7 years. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005; 9. 95(3):254–258. PMID:

16200816.

39. Rienzo VD, Minelli M, Musarra A, Sambugaro R, Pecora S, Canonica WG, et al. Post-marketing survey on the safety of sublingual immunotherapy in children below the age of 5 years. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005; 5. 35(5):560–564. PMID:

15898975.

40. Agostinis F, Foglia C, Landi M, Cottini M, Lombardi C, Canonica GW, et al. The safety of sublingual immunotherapy with one or multiple pollen allergens in children. Allergy. 2008; 12. 63(12):1637–1639. PMID:

19032238.

41. Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, McDonald HP, Yao X. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008; 4. (2):CD000011. PMID:

18425859.

42. Haynes RB, Sackett DL, Taylor DW. McMaster University. Compliance in health care. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press;1979.

43. Sabate E. World Health Organization (WHO). Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO;2003.

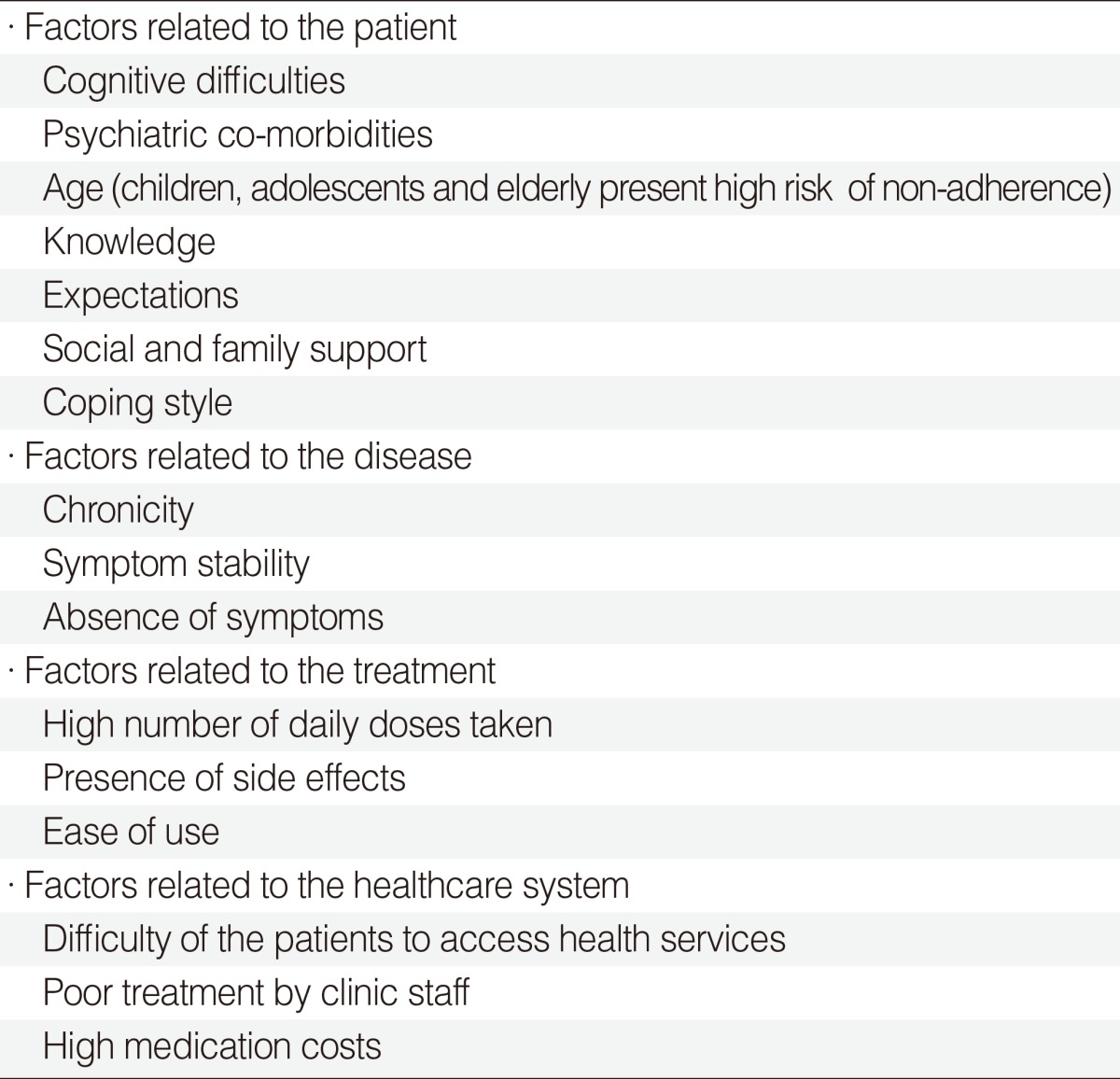

44. Passalacqua G, Baiardini I, Senna G, Canonica GW. Adherence to pharmacological treatment and specific immunotherapy in allergic rhinitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2013; 1. 43(1):22–28. PMID:

23278877.

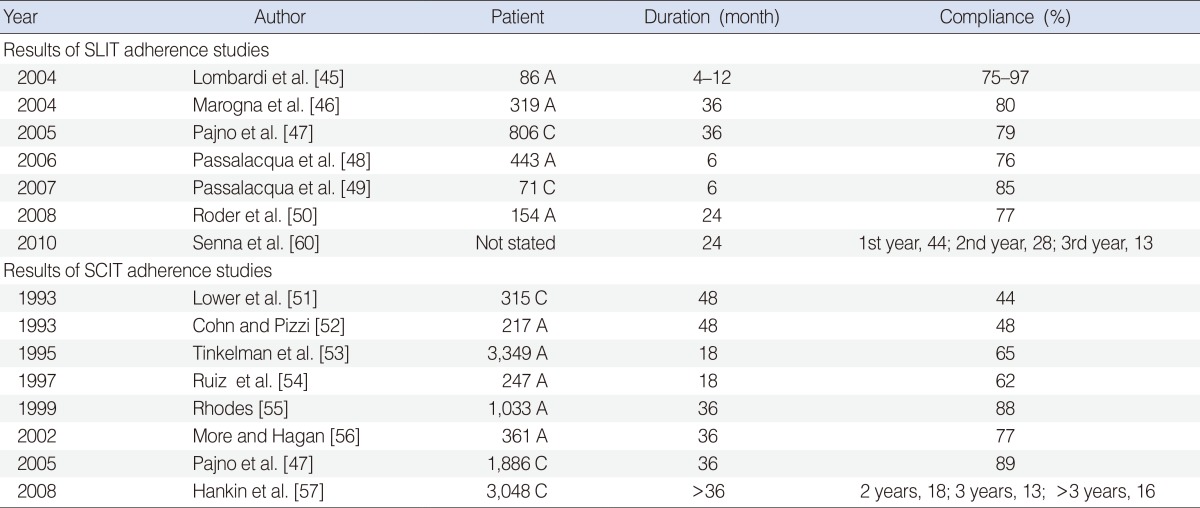

45. Lombardi C, Gani F, Landi M, Falagiani P, Bruno M, Canonica GW, et al. Quantitative assessment of the adherence to sublingual immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004; 6. 113(6):1219–1220. PMID:

15214362.

46. Marogna M, Spadolini I, Massolo A, Canonica GW, Passalacqua G. Randomized controlled open study of sublingual immunotherapy for respiratory allergy in real-life: clinical efficacy and more. Allergy. 2004; 11. 59(11):1205–1210. PMID:

15461603.

47. Pajno GB, Vita D, Caminiti L, Arrigo T, Lombardo F, Incorvaia C, et al. Children's compliance with allergen immunotherapy according to administration routes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005; 12. 116(6):1380–1381. PMID:

16337474.

48. Passalacqua G, Musarra A, Pecora S, Amoroso S, Antonicelli L, Cadario G, et al. Quantitative assessment of the compliance with a once-daily sublingual immunotherapy regimen in real life (EASY Project: Evaluation of A novel SLIT formulation during a Year). J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006; 4. 117(4):946–948. PMID:

16630956.

49. Passalacqua G, Musarra A, Pecora S, Amoroso S, Antonicelli L, Cadario G, et al. Quantitative assessment of the compliance with once-daily sublingual immunotherapy in children (EASY project: evaluation of a novel SLIT formulation during a year). Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2007; 2. 18(1):58–62. PMID:

17295800.

50. Roder E, Berger MY, de Groot H, Gerth van Wijk R. Sublingual immunotherapy in youngsters: adherence in a randomized clinical trial. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008; 10. 38(10):1659–1667. PMID:

18631346.

51. Lower T, Henry J, Mandik L, Janosky J, Friday GA Jr. Compliance with allergen immunotherapy. Ann Allergy. 1993; 6. 70(6):480–482. PMID:

8507043.

52. Cohn JR, Pizzi A. Determinants of patient compliance with allergen immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1993; 3. 91(3):734–737. PMID:

8454795.

53. Tinkelman D, Smith F, Cole WQ 3rd, Silk HJ. Compliance with an allergen immunotherapy regime. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1995; 3. 74(3):241–246. PMID:

7889380.

54. Ruiz FJ, Jimenez A, Cocoletzi J, Duran E. Compliance with and abandonment of immunotherapy. Rev Alerg Mex. 1997; Mar-Apr. 44(2):42–44. PMID:

9296824.

55. Rhodes BJ. Patient dropouts before completion of optimal dose, multiple allergen immunotherapy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1999; 3. 82(3):281–286. PMID:

10094219.

56. More DR, Hagan LL. Factors affecting compliance with allergen immunotherapy at a military medical center. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002; 4. 88(4):391–394. PMID:

11991556.

57. Hankin CS, Cox L, Lang D, Levin A, Gross G, Eavy G, et al. Allergy immunotherapy among Medicaid-enrolled children with allergic rhinitis: patterns of care, resource use, and costs. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008; 1. 121(1):227–232. PMID:

18206509.

58. Incorvaia C, Mauro M, Ridolo E, Puccinelli P, Liuzzo M, Scurati S, et al. Patient's compliance with allergen immunotherapy. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2008; 2:247–251. PMID:

19920970.

59. Han DH, Rhee CS. Sublingual immunotherapy in allergic rhinitis. Asia Pac Allergy. 2011; 10. 1(3):123–129. PMID:

22053308.

60. Senna G, Lombardi C, Canonica GW, Passalacqua G. How adherent to sublingual immunotherapy prescriptions are patients? The manufacturers' viewpoint. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010; 9. 126(3):668–669. PMID:

20816199.

61. Incorvaia C, Rapetti A, Scurati S, Puccinelli P, Capecce M, Frati F. Importance of patient's education in favouring compliance with sublingual immunotherapy. Allergy. 2010; 10. 65(10):1341–1342. PMID:

20192941.

62. Passalacqua G, Frati F, Puccinelli P, Scurati S, Incorvaia C, Canonica GW, et al. Adherence to sublingual immunotherapy: the allergists' viewpoint. Allergy. 2009; 12. 64(12):1796–1797. PMID:

19712121.

63. Bousquet J, Lund VJ, van Cauwenberge P, Bremard-Oury C, Mounedji N, Stevens MT, et al. Implementation of guidelines for seasonal allergic rhinitis: a randomized controlled trial. Allergy. 2003; 8. 58(8):733–741. PMID:

12859551.

64. Bousquet J, Van Cauwenberge P, Khaltaev N. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001; 11. 108(5 Suppl):S147–S334. PMID:

11707753.

65. Zuberbier T, Bachert C, Bousquet PJ, Passalacqua G, Walter Canonica G, Merk H, et al. GA2LEN/EAACI pocket guide for allergen-specific immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis and asthma. Allergy. 2010; 12. 65(12):1525–1530. PMID:

21039596.

66. Cox L, Nelson H, Lockey R, Calabria C, Chacko T, Finegold I, et al. Allergen immunotherapy: a practice parameter third update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011; 1. 127(1 Suppl):S1–S55. PMID:

21122901.

67. Schünemann HJ, Jaeschke R, Cook DJ, Bria WF, El-Solh AA, Ernst A, et al. An official ATS statement: grading the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations in ATS guidelines and recommendations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006; 9. 174(5):605–614. PMID:

16931644.

68. Brozek JL, Baena-Cagnani CE, Bonini S, Canonica GW, Rasi G, van Wijk RG, et al. Methodology for development of the Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma guideline 2008 update. Allergy. 2008; 1. 63(1):38–46. PMID:

18053015.

69. Bousquet J, Schunemann HJ, Zuberbier T, Bachert C, Baena-Cagnani CE, Bousquet PJ, et al. Development and implementation of guidelines in allergic rhinitis: an ARIA-GA2LEN paper. Allergy. 2010; 10. 65(10):1212–1221. PMID:

20887423.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download