This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a common disorder. It usually results from the structural compromise of the upper airway. In patients with OSA, the obstruction predominantly occurs along the pharyngeal airway, and also a variety of tumors have been reported to cause such a condition. We present here the case of a thyroglossal duct cyst causing OSA in adult. This case demonstrates that thyroglossal duct cyst or some kind of mass lesions in the airway lesions should be considered in the differential diagnosis of OSA patients.

Go to :

Keywords: Thyroglossal duct cyst, Sleep apnea syndromes, Sleep disorders

INTRODUCTION

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a highly prevalent disease that is characterized by recurrent episodes of upper airway obstruction and it usually results from the structural compromise of the upper airway accompanied with decrease in muscle tone. In patients with OSA, the obstruction predominantly occurs along the pharyngeal airway, and a variety of tumors have been reported to cause such a condition. Here we describe an interesting case of OSA with a thyroglossal duct cyst (TGDC) with preoperative and postoperative sleep videofluoroscopic findings.

Go to :

CASE REPORT

A 51-year-old man visited the Sleep Center with a 2-year history of snoring and voice change. He had complaints about loud snoring and had been witnessed to have obstructive sleep apnea with excessive daytime somnolence. His Epworth sleepiness scale (ESS) score was 13. He denied any history of dyspnea. His medical history included mild hypertension and diabetes. His height was 160 cm, his weight was 62 kg and his body mass index was 24.2 kg/m2.

On physical examination, his Friedman tongue position [

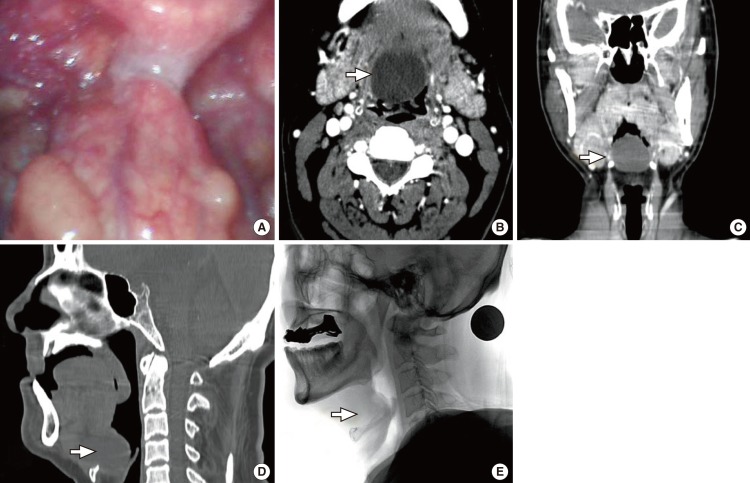

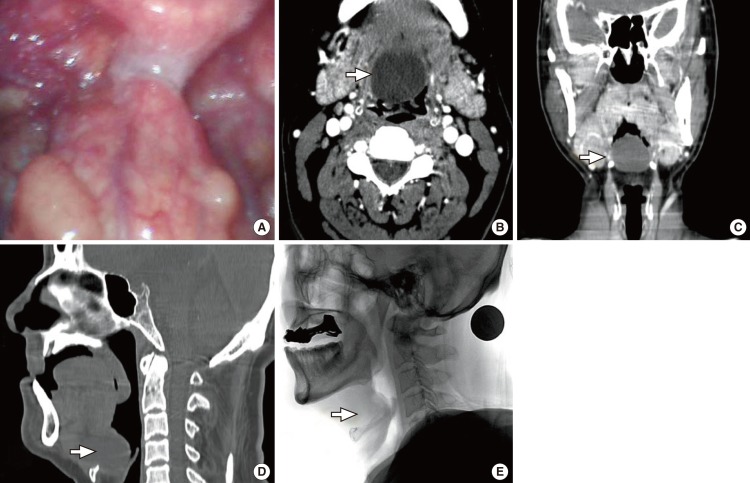

1] was grade III (only the soft palate is visible) and the tonsils were hidden in the tonsillar fossa. On flexible laryngoscopy, about a 20×20 mm sized round cystic mass at the base of tongue was identified. The cyst bended the epiglottis posteriorly, which made the airway narrow. The vocal cords could not be observed because of the lesion (

Fig. 1A).

| Fig. 1Preoperative findings of lingual thyroglossal duct cyst. (A) Stroboscopic findings of huge thyroglossal duct cyst (TGDC) in the tongue base, (B) axial, (C) coronal, and (D) saggital computed tomography scan showed midline cystic mass in the tongue base. (E) Video fluoroscopic image showed a round shadow pushing the epiglottis posteriorly.

|

He underwent a full-night laboratory nocturnal polysomnography (PSG). PSG revealed that the respiratory disturbance index (RDI) was 32.2 events per hour of sleep with the supine RDI of 105.8 events/h. The longest apnea duration was 39.7 seconds. The lowest SaO2 was 89%, and the average SaO2 saturation was 97.2%.

The computed tomograms showed a 33×31×27 mm sized well-defined cystic lesion located at the midline of the tongue base, compressing the oropharyngeal airway (

Fig. 1B, D). The epiglottis was displaced posteriorly by the cystic lesion.

To evaluate the upper airway obstruction and to find any other obstructive lesion, sleep videofluoroscopy (SVF) was performed with administration of 0.05 mg/kg of midazolam as described previously [

2]. SVF showed that the pharyngeal airway was completely obstructed during both inspiratory and expiratory phase when the mass pulled the epiglottis down and backward. The tip of epiglottis was in contact with the posterior pharyngeal wall irrespective of respiratory cycle (

Fig. 1E).

Sistrunk operation was performed via external approach instead of oral approach, because the mass was somewhat large. Round cystic mass was removed uneventfully. Soon after the operation, the signs and symptoms of OSA such as snoring and daytime sleepiness ceased and his voice was normalized. His ESS score reached 4.

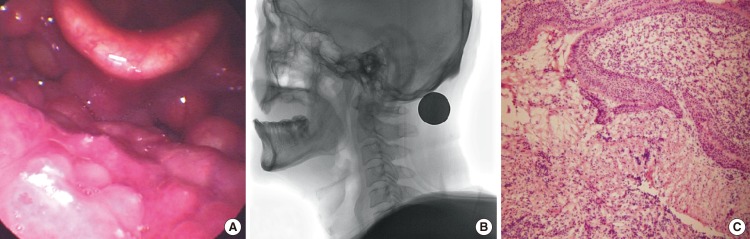

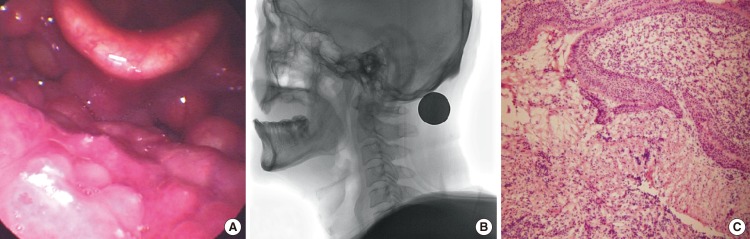

Postoperative flexible laryngoscopy showed that the mass was disappeared completely (

Fig. 2A). Postoperative PSG (3 months after operation) showed that all the parameters were nearly normalized or improved. The RDI decreased to 4.0 events per hour and the supine RDI decreased to 13.4 events per hour. The longest apnea duration was 26.5 sec. The lowest SaO2 was 92%, and the average SaO2 saturation was 97.8%.

| Fig. 2Postoperative findings. (A) Storoboscopy showed that the cystic mass was removed and (B) video fluoroscopic image showed that the round shadow of cystic mass was disappeared. (C) Histopathology showing the cyst lined by stratified squamous epithelium.

|

Postoperative SVF showed that the displaced epiglottis returned to normal position and the pharyngeal airway was not collapsed, however, during inspiration the hypopharyngeal airway was partially obstructed at the level of the epiglottis, which could explain the remnant RDI of 4.0 (

Fig. 2B).

The histopathology showed that the cyst was lined by stratified squamous epithelium, and that the deeper tissue showed fibrosis, skeletal muscle fragments and laryngeal gland cysts, which was consistent with a TGDC (

Fig. 2C). There has been no evidence of recurrence for 1 year.

Go to :

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated a case of TGDC at the tongue base, resulting in OSA syndrome with SVF findings of dynamic changes in the upper airway.

OSA is a highly prevalent disease that is typified by functional narrowing of the pharynx. The common causes of sleep apnea are bulky or retropositioned soft tissues at the palate, the base of the tongue or the retropharynx. Patients with OSA frequently have multiple anatomic abnormalities and possibly neuromuscular dysfunction causing airway collapse. The less common causes of obstructive sleep apnea include mass lesions of the pharynx, larynx and base of the tongue [

3-

11]. These include retropharyngeal lipoma, aryepiglottic fold cyst, parapharyngeal tumor such as carotid body tumor, lingual thyroid, suparglottic cyst and epiglottic cyst etc. Theroetically, any mass-like lesions around the upper airway have a potential to cause airway obstruction, resulting in OSA.

TGDCs are the most common congenital midline neck masses that arise from a tubal remnant of thyroid descent during development [

12], however, lingual TGDC, which has an isolated tongue lesion without neck mass, has been rarely reported. The differential diagnosis of this lesion could be a TGDC or a vallecular cyst. When a cystic lesion was buried in the tongue base and close to the hyoid bone or the foramen cecum, a lingual TGDC is more likely than the vallecular cyst. Vallecular cysts are more often attached to the epiglottis or vallecular sulcus with broad base [

13]. Pathologic studies cannot differentiate the tongue base cystic lesions, because the epithelial lining of lingual TGDCs and vallecular cysts are quite similar and pathologists tend to rely on the clinical impressions. In our case, the large cystic lesion lied in the midline in close proximity to hyoid bone so that it favors a lingual TGDC more than a vallecular cyst.

There have been some reports on TGDC causing apnea in infants [

14-

16], however, a TGDC case causing apnea in adult have not been reported, to our knowledge. Most of lingual TGDC cases were pediatric patients and there has been few case reports of adult lingual TGDC with dyspnea [

17] or with asphyxia [

18].

The position and size of the cysts determine the clinical presentation and cystic lesions could be asymptomatic in whole life. These cysts may be found incidentally in adults or they may present as swelling as a result of associated infection. Once the lesion is identified, complete cyst excision is the treatment of choice. The treatment of lingual TGDC includes external surgical resection, endoscopic laser-assisted resection or marsupialization.

The use of flexible laryngoscopes allows a thorough examination of the larynx and pharynx, and this can be easily performed in the outpatient setting. Our case points out the necessity of a full upper airway examination, including endoscopic and radiological evaluation for patients who present with symptoms of OSA.

SVF is a valuable tool for the evaluation of the upper airway obstruction and was first introduced in 1981 with the name of somnofluoroscopy [

19]. It has been recently introduced to evaluate the changes and obstruction sites of the upper airway in patients with OSA in our hospital [

2,

20,

21]. In this patient, SVF provided dynamic information on the position of the mass in the upper airway, which was displacing the epiglottis posteriorly to the posterior pharyngeal wall, resulting in obstruction of the upper airway. After surgical removal of the mass, SVF showed that the displaced epiglottis returned to natural position and showed the patent airway.

In conclusion, for patients with OSA symptoms, a thorough examination of the upper airway including flexible laryngoscopes is needed and mass lesion such as TGDC should be included in the differential diagnosis. SVF could give us additional information on dynamic changes of the upper airway.

Go to :

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The present research was conducted by the research fund of Dankook University in 2010.

Go to :

Notes

Go to :

References

1. Friedman M, Ibrahim H, Joseph NJ. Staging of obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome: a guide to appropriate treatment. Laryngoscope. 2004; 3. 114(3):454–459. PMID:

15091218.

2. Lee CH, Mo JH, Seo BS, Kim DY, Yoon IY, Kim JW. Mouth opening during sleep may be a critical predictor of surgical outcome after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty for obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010; 4. 6(2):157–162. PMID:

20411693.

3. Hockstein NG, Anderson TA, Moonis G, Gustafson KS, Mirza N. Retropharyngeal lipoma causing obstructive sleep apnea: case report including five-year follow-up. Laryngoscope. 2002; 9. 112(9):1603–1605. PMID:

12352671.

4. Picciotti PM, Agostino S, Galla S, Della Marca G, Scarano E. Aryepiglottic fold cyst causing obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep Med. 2006; 6. 7(4):389. PMID:

16713345.

5. Smadi T, Raza MA, Woodson BT, Franco RA. Obstructive sleep apnea caused by carotid body tumor: case report. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007; 8. 3(5):517–518. PMID:

17803016.

6. Barnes TW, Olsen KD, Morgenthaler TI. Obstructive lingual thyroid causing sleep apnea: a case report and review of the literature. Sleep Med. 2004; 11. 5(6):605–607. PMID:

15511710.

7. Veitch D, Rogers M, Blanshard J. Parapharyngeal mass presenting with sleep apnoea. J Laryngol Otol. 1989; 10. 103(10):961–963. PMID:

2584857.

8. Walshe P, Smith D, Coakeley D, Dunne B, Timon C. Sleep apnoea of unusual origin. J Laryngol Otol. 2002; 2. 116(2):138–139. PMID:

11827591.

9. Chen MF, Fang TJ, Lee LA, Li HY, Wang CJ, Chen IH. Huge supraglottic cyst causing obstructive sleep apnea in an adult. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006; 12. 135(6):986–988. PMID:

17141104.

10. Henderson LT, Denneny JC 3rd, Teichgraeber J. Airway-obstructing epiglottic cyst. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1985; Sep-Oct. 94(5 Pt 1):473–476. PMID:

4051405.

11. Dahm MC, Panning B, Lenarz T. Acute apnea caused by an epiglottic cyst. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1998; 1. 42(3):271–276. PMID:

9466231.

12. Koeller KK, Alamo L, Adair CF, Smirniotopoulos JG. Congenital cystic masses of the neck: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1999; Jan-Feb. 19(1):121–146. PMID:

9925396.

13. Suh MW, Sung MW. Apnea spells in an infant with vallecular cyst. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2004; 9. 113(9):765. PMID:

15453537.

14. Diaz MC, Stormorken A, Christopher NC. A thyroglossal duct cyst causing apnea and cyanosis in a neonate. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2005; 1. 21(1):35–37. PMID:

15643322.

15. Eom M, Kim YS. Asphyxiating death due to basal lingual cyst (thyroglossal duct cyst) in two-month-old infant is potentially aggravated after central catheterization with forced positional changes. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2008; 9. 29(3):251–254. PMID:

18725783.

16. Hanzlick RL. Lingual thyroglossal duct cyst causing death in a four-week-old infant. J Forensic Sci. 1984; 1. 29(1):345–348. PMID:

6699603.

17. Wu PY, Friedman M, Huang SC, Lin HC. Radiology quiz case 1: Adult lingual thyroglossal duct cyst (TGDC). Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009; 7. 135(7):716. 718. PMID:

19620596.

18. Sauvageau A, Belley-Cote EP, Racette S. Fatal asphyxia by a thyroglossal duct cyst in an adult. J Clin Forensic Med. 2006; Aug-Nov. 13(6-8):349–352. PMID:

17027318.

19. Fodor J 3rd, Malott JC, Colley DP, Walsh JK, Kramer M. Somnofluoroscopy. Radiol Technol. 1981; Sep-Oct. 53(2):105–109. PMID:

7339697.

20. Lee CH, Mo JH, Kim BJ, Kong IG, Yoon IY, Chung S, et al. Evaluation of soft palate changes using sleep videofluoroscopy in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009; 2. 135(2):168–172. PMID:

19221245.

21. Lee CH, Kim JW, Lee HJ, Yun PY, Kim DY, Seo BS, et al. An investigation of upper airway changes associated with mandibular advancement device using sleep videofluoroscopy in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009; 9. 135(9):910–914. PMID:

19770424.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download