Abstract

Oncogenic osteomalacia is a rare cause that makes abnormalities of bone metabolism. Our case arose in a 47-year-old woman presenting a nasal mass associated with osteomalacia. We excised the mass carefully. After surgery, it was diagnosed as hemangiopericytoma and her symptoms related with osteomalacia were relieved and biochemical abnormalities were restored to normal range. We report and review a rare case of nasal hemangiopericytoma that caused osteomalacia.

Oncogenic osteomalacia is a very rare cause of osteomalacia. It is treated by surgical tumor resection. This tumor makes paraneoplastic syndrome like hypophosphatemic osteomalacia with hyperphosphaturia, low plasma 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D and usually a normal serum calcium, parathormone, and 25-hydroxyvitamin D [1]. Clinical features are bone pain, atrophy of proximal muscles and gait disturbance. Phosphaturia of oncogenic osteomalacia is from phosphaturic factor such as fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF 23) that is secreted from tumor [2]. Among these tumors that cause osteomalacia, 10 cases have been reported worldwide in the ethmoid sinus [3-8]. We report a case of nasal hemangiopericytoma causing oncogenic osteomalacia and review the literature.

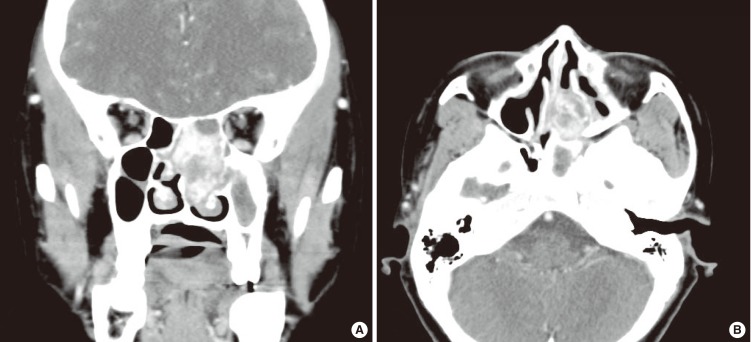

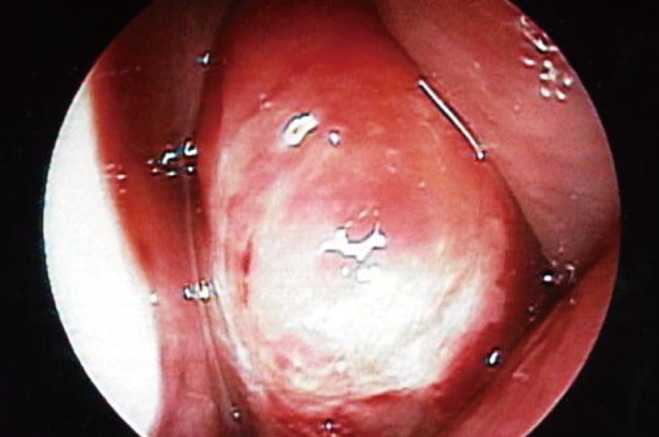

A 47-year-old woman presented with stuffy nose, postnasal dripping from 8 months ago. She had suffered from bone pains since a couple of years ago. Pain in the foot began in 3 years ago and it also developed gradually in her lower leg and back. Fracture of the right femur and osteopenia was detected on general radiographs. She underwent conservative treatment and diagnostic workup. She was diagnosed as osteomalacia and took calcium and phosphate. On past medical history, the patient underwent a endoscopic surgery for sinusitis with polyp at 7 years ago. She had no remarkable family history. Nasal endoscopy revealed a smooth pinkish hard mass filling the left nasal cavity. It was extended to superior nasal meatus and made lateral displacement of nasal septum and middle turbinate (Fig. 1). No abnormalities were noted in physical examination of other head and neck area. Nasal computed tomography revealed a expansile hypervascular tumor with dimensions of 3×3×1 cm located in the left nasal cavity and posterior ethmoid sinus. The mass demonstrated a scattered calcification and expansive bony destruction (Fig. 2). Laboratory examinations before surgery showed hypophosphatemia, normocalcemia, high serum alkaline phophatase, normal parathormone, normal serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D. Subsequently, the patient underwent a biopsy, the histology revealed findings that were highly suggestive of fibroma. On the basis of these findings, the patient didn't undergo selective angiography prior to surgery. We performed wide excision with about 5 mm free margin via endoscopic route under general anesthesia. It was difficult that we dissect the mass because of adhesion to skull base and sphenoid sinus. There was significant bleeding during the excision and the amount of bleeding was around 300 mL, but hemostasis was readily obtained with bipolar cautery and packing. Pathologic examination of the resected mass that was taken from the left nasal cavity showed hemangiopericytoma (Fig. 3). On follow-up 1 month later her plasma phosphate returned to within normal limits, and she had clinical improvement of her bone pains and general activities. This resulted in a diagnosis of oncogenic osteomalacia.

Osteomalacia is a bone disease resulting from inadequate mineralization. The clinical features are muscle weakness, bone pain, bone fractures secondary to minor trauma. Laboratory findings related to the oncogenic osteomalacia are a low serum phosphate level with inadequately normal calcium, low-normal 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D levels, phosphaturia [1].

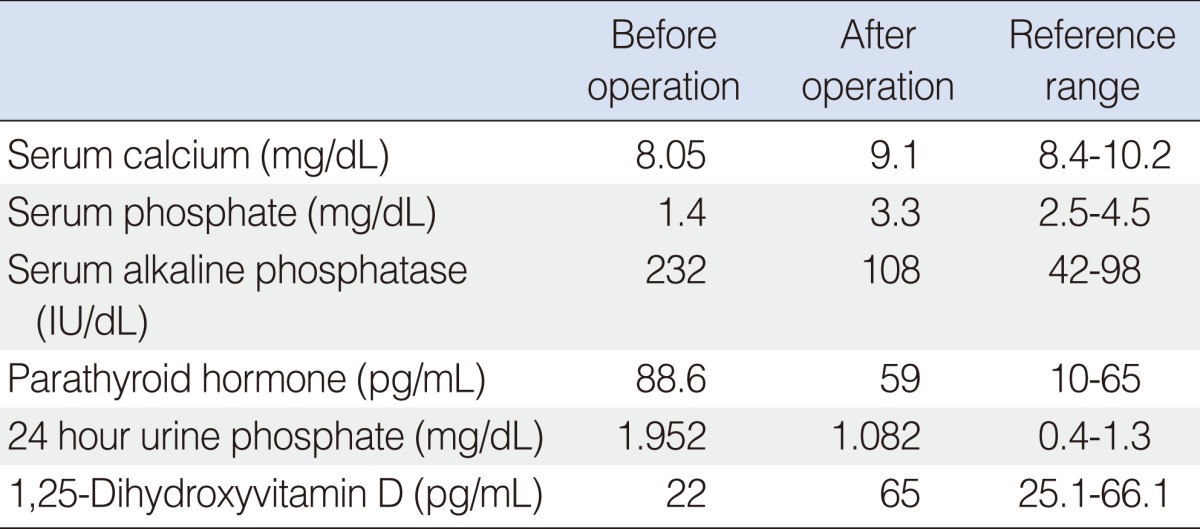

Our patient also showed characteristic biochemical abnormalities (Table 1). Oncogenic osteomalacia is a rare cause of osteomalacia. It is developed from the presense of a mesenchymal tumor. It is thought that the tumor release of FGF-23, which inactivates the sodium-phosphate pump in the proximal tubule of the kidney, prevents reabsorption of phosphate [9], and decreasing the activity in 1-hydroxylation of 25-hydroxyvitamin D [10]. These mechanisms makes the biochemical abnormalities. Our patient was previously diagnosed with osteomalacia at the rheumatology department of other hospital and had been treated with phosphate compensation. However, her symptoms weren't resolved. On physical examination, we noted an intranasal mass. We could have concern for oncogenic osteomalacia. In the oncogenic osteomalacia, the mean age at onset of symptoms is 40 years and it is developed equally in both sexes [8]. Magnetic resonance imaging is the imaging study of choice in the investigation of oncogenic osteomalacia. If it is unhelpful or equivocal, computed tomography scan should be undertaken. Octreotide scintigraphy can also use in locating these lesions [7]. The tumor should be surgically resected with a wide margin. Unfortunately, there are no consensus about the area of wide resection margin on the previous literature, however we believe that the tumor must be surgically excised with a wide margin of resection to prevent recurrences. And preoperative embolization is applied because of its significant vascular component. Radiotherapy and chemotherapy have proved useless in these tumors [8]. After neoplasm removal, symptoms of osteomalacia and metabolic abnormalities are rapidly restored [11]. Ten ethmoid tumors causing oncogenic osteomalacia have been reported. Histologically, 2 cases were mesenchymal tumors and 8 cases were hemangiopericytomas [3-8]. In our case, pathologic examination revealed hemangiopericytoma which is considered main cause of oncogenic osteomalacia. The sinonasal variant of hemangiopericytoma generally has a more benign clinical course than tumor arising at the non head and neck areas [12]. Other benign tumors such as hemangioma, angiofibroma, hemangioendothelioma, giant cell tumor, nonossifying fibroma, osteoblastoma, and chondroma could be associated with osteomalacia. It was also reported with regard to malignant tumors which were osteosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, synovial sarcoma, angiosarcoma, and malignant fibrous histiocytoma. Our report is distinguished with previous ones because since she had suffered from osteomalacia, multiple survey scans of her body were done, but no abnormalities were discovered for 2 years. We could see an underlying tumor after 2 year follow-up. Oncogenic osteomalacia is a little unfamiliar to otolaryngologists. So it makes difficulty to make diagnosis. However, we should be effort to discover underlying tumors which cause oncogenic osteomalacia. When intranasal or head and neck masses are revealed from the patients who have past history of osteomalacia, We should keep in minds the possibility of oncogenic osteomalacia.

In conclusion, Hemangiopericytoma involving nasal sinuses can be associated with osteomalacia as a part of paraneoplastic syndrome. When some patient presents nasal mass with osteomalacia, oncogenic osteomalacia should be suspected and a thorough examination should be conducted. And surgical resection is effective in normalizing symptoms of osteomalacia.

References

1. Nelson AE, Robinson BG, Mason RS. Oncogenic osteomalacia: is there a new phosphate regulating hormone? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1997; 12. 47(6):635–642. PMID: 9497867.

2. Jonsson KB, Zahradnik R, Larsson T, White KE, Sugimoto T, Imanishi Y, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 in oncogenic osteomalacia and X-linked hypophosphatemia. N Engl J Med. 2003; 4. 348(17):1656–1663. PMID: 12711740.

3. Kawai Y, Morimoto S, Sakaguchi K, Yoshino H, Yotsui T, Hirota S, et al. Oncogenic osteomalacia secondary to nasal tumor with decreased urinary excretion of cAMP. J Bone Miner Metab. 2001; 19(1):61–64. PMID: 11156476.

4. Fuentealba C, Pinto D, Ballesteros F, Pacheco D, Boettiger O, Soto N, et al. Oncogenic hypophosphatemic osteomalacia associated with a nasal hemangiopericytoma. J Clin Rheumatol. 2003; 12. 9(6):373–379. PMID: 17043447.

5. Inokuchi G, Tanimoto H, Ishida H, Sugimoto T, Yamauchi M, Miyauchi A, et al. A paranasal tumor associated with tumor-induced osteomalacia. Laryngoscope. 2006; 10. 116(10):1930–1933. PMID: 17003734.

6. Beech TJ, Rokade A, Gittoes N, Johnson AP. A haemangiopericytoma of the ethmoid sinus causing oncogenic osteomalacia: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007; 10. 36(10):956–958. PMID: 17498926.

7. Kenealy H, Holdaway I, Grey A. Occult nasal sinus tumours causing oncogenic osteomalacia. Eur J Intern Med. 2008; 11. 19(7):516–519. PMID: 19013380.

8. Gonzalez-Compta X, Manos-Pujol M, Foglia-Fernandez M, Peral E, Condom E, Claveguera T, et al. Oncogenic osteomalacia: case report and review of head and neck associated tumours. J Laryngol Otol. 1998; 4. 112(4):389–392. PMID: 9659507.

9. Shimada T, Mizutani S, Muto T, Yoneya T, Hino R, Takeda S, et al. Cloning and characterization of FGF23 as a causative factor of tumor-induced osteomalacia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001; 5. 98(11):6500–6505. PMID: 11344269.

10. Wilkins GE, Granleese S, Hegele RG, Holden J, Anderson DW, Bondy GP. Oncogenic osteomalacia: evidence for a humoral phosphaturic factor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995; 5. 80(5):1628–1634. PMID: 7745010.

11. Furco A, Roger M, Mouchet B, Richard O, Martinache X, Fur A. Osteomalacia cured by surgery. Eur J Intern Med. 2002; 2. 13(1):67–69. PMID: 11836086.

12. Catalano PJ, Brandwein M, Shah DK, Urken ML, Lawson W, Biller HF. Sinonasal hemangiopericytomas: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of seven cases. Head Neck. 1996; Jan-Feb. 18(1):42–53. PMID: 8774921.

Fig. 2

Preoperative contrast-enhanced coronal (A) and axial (B) computed tomography scan revealed a expansile hypervascular tumor in the left nasal cavity and post ethmoid sinus that demonstrated a scattered calcification and expansive bony destruction.

Fig. 3

(A) Histologic findings of the tumor. Microscopically, this tumor is composed of mainly spindle cells, abundunt blood vessels and metaplastic bony tissues. Spindle cells are interspersed between blood vessels. (B) In immunohistochemical studies, endothelial cells of blood vessels have immunoreactivity for CD34.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download