INTRODUCTION

Nasal septal perforation is an important problem for otolaryngology specialists and facial plastic surgeons. Several factors contribute to this problem as a surgical challenge. The surgical area in septal perforations has often been previously operated on, in which case fibrotic areas that have a limited tissue and impaired blood supply may be present (

1). Nasal mucosa is almost always atrophic and is an unsuitable material for reconstruction. Even with open techniques, the surgical field is narrow (

2), and the recommended techniques are not easy to perform without extensive experience (

3). When this condition becomes symptomatic, it affects the patient's quality of life. Surgery is not recommended in cases of asymptomatic perforation, but even when symptomatic; it is often difficult to select the most suitable cases and the most appropriate techniques (

2). This is why surgical outcomes are not always positive (

4). Despite numerous surgical methods and many reconstructive materials, no single surgical procedure exists for septal perforation repair (

5). Autogenous tissues, such as temporal fascia, septal and auricle cartilage, cranial periosteum, perichondrium, and ethmoidal and hip bone, have previously been used for the closure of septal perforations.

Biomaterials, such as Dacron, porous polyethylene, dolomite, and bioglass, can be used to produce grafts of adequate sizes and shapes. With their use, donor site morbidity can be avoided. The major disadvantages of biomaterials are infection which will result with failure of closure of the septal perforation.

The aim of our study was to evaluate the effect of a porous alloplastic implant, high-density porous polyethylene (HDPP; Medpor; Porex Surgical Products Group, Newnan, GA, USA), covered with fascia lata on nasal septal perforation in rabbits.

Go to :

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Twenty (10 male, 10 female) healthy New Zealand albino rabbits were used. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Istanbul University, Istanbul Medicine faculty in the DETAM department. The whole study, including the operations and post-operative care, was performed at Istanbul University in the Veterinary Medicine Anatomy department.

Room humidity was between 40% and 60%; room temperature was maintained at 21℃. The rabbits, when under general anaesthesia, were warmed by an electrical heater to maintain their normal body temperature. Oral temperatures of the animals were stabilised at 37.5-39℃. The rabbits' weights were 3,700-4,400 g.

The animals were operated on under the general anaesthesia. The 20 rabbits were divided into study and control groups. For the study group, HDPP covered with fascia lata was implanted into the perforated area. For the control group, HDPP was implanted with no fascial covering. The rabbits were painlessly sacrificed after 4 months of observation and septal macroscopic and histological results were evaluated. The results were compared between the two groups.

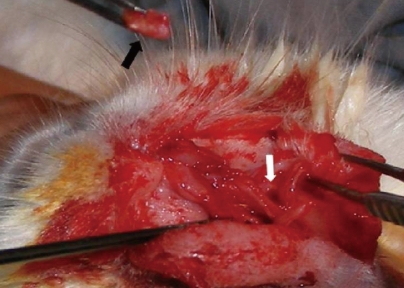

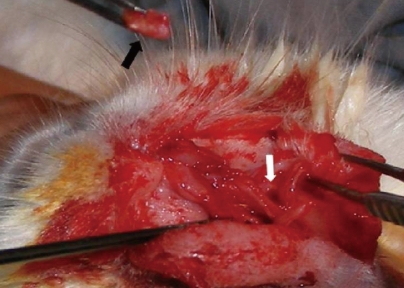

Rabbits were operated on under 7.5-15 mg/kg xylazine and 40-60 mg/kg ketamine anaesthesia. A lateral incision was made from the lateral aspect of the left nares to the incisura nasomaxillaris. After exposure of the cavum nasi, the nasal perichondrium and mucosa were elevated bilaterally. A full-thickness 0.5×0.5-cm perforation was created. Bilateral mucosa, mucoperichondrium, and septal cartilage were removed. The perforation was created with a No. 11 surgical blade. In the study group, a fascia lata graft was obtained from the femoral region. The HDPP implant was cut to an appropriate size and covered with fascia lata. The material, which was wider than the perforation, was placed between the mucoperichondrial layers as an interposition graft (

Figs. 1 and

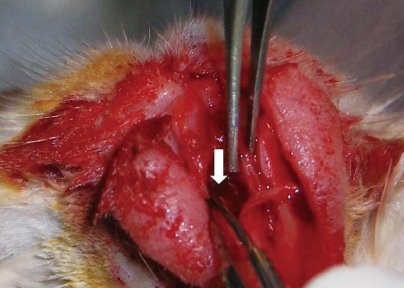

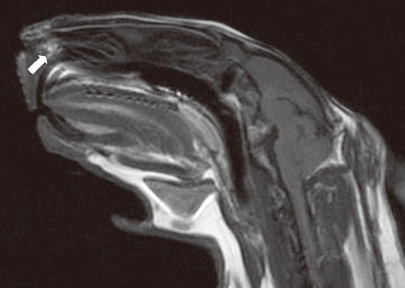

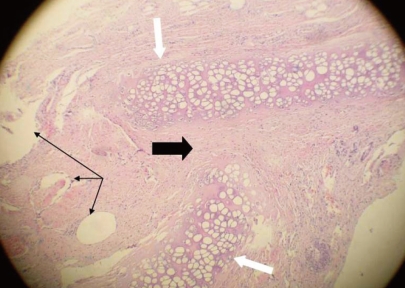

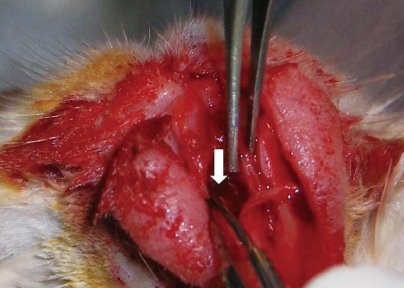

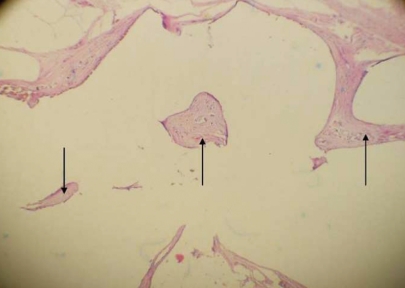

2). No suture was used to stabilise the graft. The incision lines were sutured and the animals were allowed to wake up. For the control group, HDPP was implanted without fascial covering in the same manner. Methylprednisolone sodium succinate (0.5-2 mg/kg) was administered intramuscularly on the first post-operative day, and cefazolin sodium (10 mg/kg) was administered two times daily for 5 days. Butorphanol (0.1-0.5 mg/kg) was administered intravenously two times daily for post-operative pain. B-complex vitamins (1-2 mg/kg) were also administered in the post-operative period. Four months after the procedure, the first magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan was obtained to evaluate graft condition. The MRI slice thickness was 4.5 mm, and there was no gap between the slices (consecutive slices). The animals were then sacrificed with sodium pentothal in the ear vein under ketamine anaesthesia. The animals' nasal septums were completely removed for macroscopic and histopathological examination. Sections of each septum were stained with haematoxylin and eosin and evaluated under ×100 magnification.

| Fig. 1Fascia lata-covered high-density porous polyethylene implant (black arrow) and its placement in the nasal septum (white arrow).

|

| Fig. 2Replacement of cartilage into the nasal septum (white arrow).

|

Statisitical analyses were performed using NCSS 2007 and PASS 2008 (NCSS, Kaysville, UT, USA). Fisher's exact test was used to compare the septal perforation rates between the study and control groups. The confidence interval was 95%, and a P-value of <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Go to :

DISCUSSION

Nasal septal perforations are anatomical defects that may include cartilaginous and bony tissues of the nasal septum. Perforation leads to communication of areas between the two nasal cavities, which may impair airflow and pressure (

2). This results in dynamic alterations in nasal function, leading to various symptoms in patients (

3). Wider, more anterior septal perforations tend to be more symptomatic than smaller, more posterior ones. Surgery is primarily recommended when the patient has symptoms, such as nose bleeds, crusting, or nasal obstruction. Although the prevalence of each aetiology has differed over the last two decades (

4), previous nasal surgery is still the leading factor in most of the cases (

3). Other possible aetiologies of nasal septal perforations include nasal cauterisation, nasal packing, nasal/septal fractures or haematomas, neoplasia, self-mutilation, chronic rhinitis, allergy, rhinitis, Wegener's granulomatosis, sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, toxic metals (arsenic and chrome), drugs (steroids), and narcotising agents (cocaine).

Perforations can be repaired with closed (closed endonasal, endoscopic, or unilateral hemi-transfixion) or open (external/septoplasty, rhinoplasty, or mid-facial de-gloving) techniques (

2,

5). There are two main techniques for surgical closure. One is to close the perforation with flaps, and the other is to use autografts or allografts (temporal fascia, mastoid periosteum, nasal septal material, acellular human dermal graft, conchal cartilage, or porcine small intestinal mucosa), which is interposed between the mucosal flaps (

6,

7). These techniques can be used alone or in combination. The donor site of the flaps can be changed (

8). Grafts have been designed in different shapes and sizes (

5) with varying success rates (

6). Literature data indicate that interposition grafts with mucosal flaps are more commonly used than pure mucosal flaps, with a 90% success rate (

7). Healing is reportedly better when the grafts are placed between repaired flaps (

5).

Especially in the case of large perforations, it is difficult to find adequate graft material from the human body. Our study was designed to present an alternative graft material that can be used in septal perforations. The difficulty in finding adequately wide, flat, and thin interposition grafts has caused researchers explore to synthetic materials. HDPP has been used as a synthetic replacement material since 1947 (

9,

10). Previous studies have demonstrated the successful use of implants in rhinoplasty (e.g., as spreader grafts, for correction of saddle nose deformity) (

1). The pores in HDPP are 150-200 µm (

10). The porous nature of the implant allows for connective tissue ingrowth. In a previous experiment, integration between the surface and the pores of the material was observed from the 14th day. After 3 months, remodeling of the bone and fibrous tissue were observed in the interface region (

11). To our knowledge, this is the first reported experimental study of HDPP implants used to close septal perforations. We previously demonstrated the successful use of HDPP in tracheal reconstruction in New Zealand rabbits (

12), and for this study, we chose the same material and animal model.

Although HDPP is used in different parts of the body, its use in rhinologic procedures resulted in some degree of implant failure. A disadvantage of using synthetic material is such failure. Failure of the material is due primarily to infection and the direct contact of the material with an infected environment. Until integration and fibrous tissue ingrowth occur, the implants have no vascular supply. This is important in cases involving bacterial contamination because no immune entities or antibiotics will reach the implant area (

10). To avoid bacterial contamination, especially in rhinologic procedures, it is necessary to preserve the mucosa and avoid mucosal tears. Such tears can lead to contamination, which will result in infection and removal of the implant (

1). To decrease the potential for infection, in the study group, we covered the HDPP with autogenic material to protect it from the infected environment. Fascia was chosen for this purpose; fascia has very low metabolic requirements and allows for vascularisation and tissue growth on its surface (

10). Although temporal fascia is readily obtained in humans, we choose fascia lata in our rabbits because it is difficult to obtain temporal fascia from rabbits. Covering autograft material was previously used in another study; Ribeiro and da Silva (

13) used temporal fascia-covered auricular or septal cartilage to repair 258 perforations. The perforation sizes were 1.0-3.5 cm, and the graft was used with bilateral intranasal sub mucoperichondrial or sub-mucoperiosteal advancement flaps in closed rhinoplasty. The perforations closed in 257 of 258 subjects.

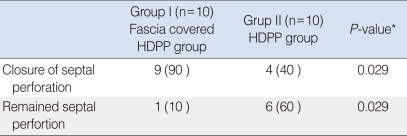

In our study, the HDPP piece was cut wider than the perforation and the fascia was laid onto the piece and sutured. The physical examination at 4 months and the MRI revealed that fascia lata-covered HDPP remained intact in nine of 10 animals; no remained perforation was observed in these animals. The perforations were macroscopically closed in nine of 10 cases. Histopathological examination showed that the graft material remained on the edge of the perforation. In the control group, a high remaining perforation rate was observed (60%). This was due to direct contact of implant with the intranasal environment, as mentioned previously. The fascia lata-covered HDPP had significantly better septal perforation closure rates than did uncovered HDPP (P=0.029).

This study has some limitations. First, perforation and closure were performed in one stage. The graft was interposed immediately after the perforation was created. It would be better to assess the effectiveness of a graft in a long-lasting perforation instead of performing an immediate replacement. The nasal septum and mucosa is extremely thin in rabbits, and it would have been difficult to replace the material after a long period. Another limitation was the follow-up period. In a study by Godin et al. (

14), the failure period of a different implant material, Goretex, was prolonged to 44 months. Long-term results would have allowed for more accurate determination of long-term success rates and will be the topic of another study. However, we believe that a 4-month follow-up period is long enough to obtain experimental results in a study such as ours.

This paper focused on Medpore, its high implant failure rates, and a possible solution to avoid this failure. Thus, Medpore covered with fascia lata was only compared with uncovered Medpore. This is another limitation of this study, the absence of a control group to evaluate the usefulness of fascia alone. HDPP covered with fascia lata is an effective material for use in the repair of nasal septal perforations. It is easy to work with and avoids the increased operative time and morbidity associated with harvesting autografts.

Especially in cases of large perforations, it is difficult to obtain wide, flat, and thin grafts. HDPP is an option for septal perforation closure in humans. However, like other synthetic materials, HDPP has some degree of failure. Covering HDPP with fascia lata decreased the remained perforation rate by protecting the implant from the contaminated environment. Additional studies are needed to demonstrate the safety of this material, and long-term follow-up is needed to clarify the long-term success rates.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download