Abstract

Nasal dermoid sinus cysts are the most common congenital midline nasal lesion, accounting for 1% to 3% of all dermoid cysts, and 4% to 12% of all head and neck dermoids. Selection of the appropriate reconstruction technique, after dermoid resection, is important for treatment. Here we describe the successful management of a case with a nasal dermoid sinus cyst using an open rhinoplasty approach, and primary reconstruction using Tutoplast-processed fascia lata and crushed septal cartilage.

Nasal dermoid sinus cysts (NDSC) are the most common congenital midline nasal lesion, accounting for 1% to 3% of all dermoid cysts, and 4% to 12% of head and neck dermoids (1, 2). NDSCs may appear as a cystic mass or sinus opening on the midline nasal dorsum between the glabella and the columella at birth, or during early childhood (3). Complete excision of NDSCs, regardless of extension, is essential to prevent recurrence, nasal deformity, infection, meningitis, and intracranial abscess formation (4, 5). Among the surgical approaches used for the treatment of NDSCs are: excision and primary closure, midline vertical incision, transverse incision, lateral rhinotomy, inverted-U incision, and external rhinoplasty (6, 7). Open rhinoplasty is the preferred approach, since it provides advantages over the standard incisions, including better cosmetic results, wide exposure and more control over osteotomies, and better visualization of the cribriform plate (7). The selection of the appropriate reconstruction technique, after dermoid resection, however, is also important. Autologous septal or costal cartilage has been used for the repair of a dorsal defect (8-10). Among the limitations of autologous graft material in pediatric patients is an insufficient amount of septum and separate donor site morbidity. Moreover, it may be necessary to reinforce the nasal dorsal skin, which is damaged by the disease itself as well as the resection procedure. Thus, the availability of other graft material might help solve some of these complicated problems. Here we report the successful management of NDSC using an open rhinoplasty approach and primary reconstruction using crushed septal cartilage and tutoplast-processed fascia lata (TPFL).

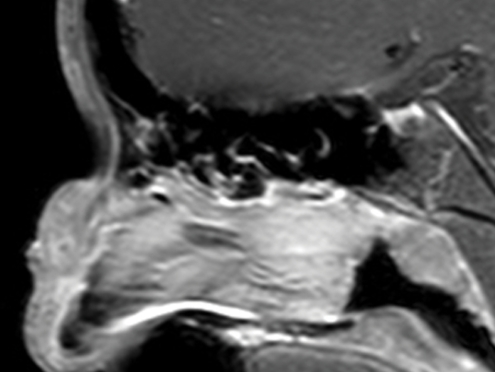

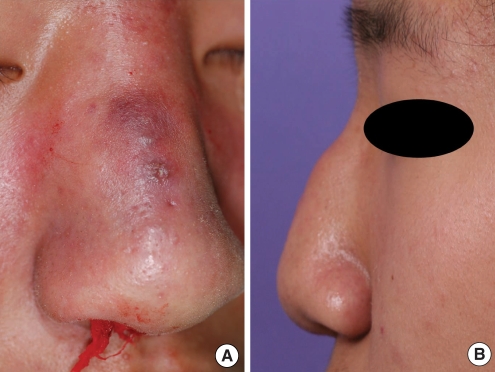

A 14-yr-old boy presented with pain, redness, and swelling of the nasal dorsum after being hit in the nose. At birth, this patient had a visible pit on the nasal dorsum, and intermittent discharge was present since early childhood. Physical examination revealed a pit with discharge on a swollen and reddish dorsum (Fig. 1). The other head and neck findings were within normal limits. A preoperative magnetic resonance imaging scan revealed an enhancing soft tissue lesion on the nasal dorsum and a tortuous sinus tract, from the nasal skin to the nasal septum (Fig. 2). There was no evidence, however, of intracranial extension. The skin infection was controlled by oral antibiotics for 4 weeks.

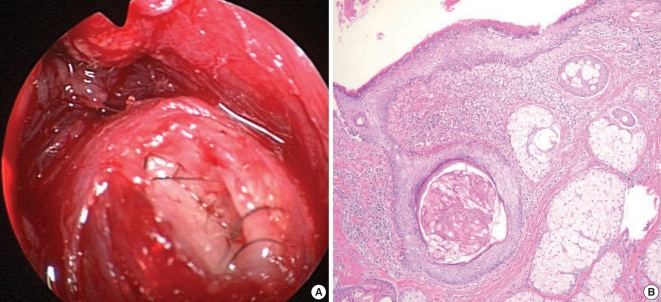

The patient underwent complete removal of the NDSC by open rhinoplasty. Following the transcollumelar and bilateral marginal incisions, both the lower and upper lateral cartilages were delineated. We noted an ill-defined cystic lesion containing hair (Fig. 3A) and involving the upper lateral cartilage, dorsal septum, and nasal bones. The nasal pit was removed using a small elliptical skin incision, on the nasal dorsum and the lesion, and dissected from the upper lateral cartilages, dorsal septum, and nasal bone. However, the preexisting severe inflammation led to the rupture of the cystic lesion and severe adhesion to the surrounding tissue; hence, complete en bloc excision could not be achieved. The residual lesion was removed using a microdebrider under endoscopic guidance. After removal of the lesion, there were significant nasal defects, including an open roof deformity and decreased projection of the nasal dorsum. Both upper lateral cartilages were sutured to the nasal septal cartilage using 4-0 polydioxanone.

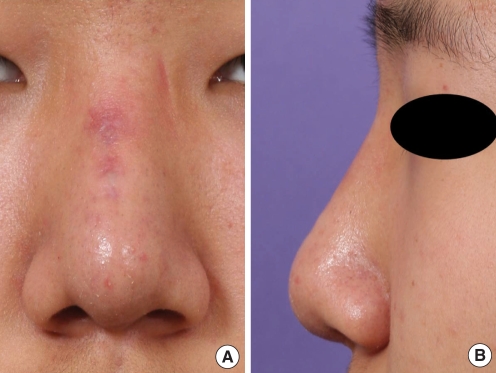

The dorsal defect and irregularities were reconstructed using crushed cartilage harvested from the nasal septum and four-layered TPFL strips (30×40 mm, Tutoplast®, Tutogen Medical GmbH, Industriestrasse, Germany), as described previously (11). The TPFL was rehydrated in saline solution for more than 5 min before use and cut into long strips approximately 1 cm in width. The cephalic end of each four-layered strip had a stepladder pattern for smooth elevation of the radix area, and the caudal ends of all strips were rounded using iris scissors. This stack of TPFL strips was inserted into the dorsum, and crushed septal cartilage was inserted under the strips. This was followed by intercrural and interdomal sutures and an onlay graft to produce adequate nasal tip projection. The dorsal skin and rhinoplasty incisions were closed with 6-0 nylon sutures, and a nasal aqua splint was placed over the nasal dorsum.

Most repairs of nasal defects after NDSC excision using an open rhinoplasty approach have used autologous septal and costal cartilages as graft materials for reconstruction (8-10). Although autologous cartilage is the material of choice for dorsal augmentation, the amount of harvested septal or conchal cartilage is often insufficient; in addition, costal cartilage has been associated with donor site morbidity.

Although we initially attempted to reconstruct the defect in this patient using only septal cartilage, the amount harvested was only about 1.5×1.5 cm2, an amount insufficient for dorsal augmentation. In the nose of Asians, the septal cartilage is relatively small, and younger patients have even smaller amounts of cartilage and require preservation of the large L-strut. Moreover, in this patient, some dorsal irregularity persisted, and the skin had been thinned by aggressive removal of the ruptured cystic lesion using a microdebrider. Autologous fascia and costal cartilage were also available, but the patient's parents were reluctant to approve a separate donor site incision for harvest. In addition, synthetic graft material has a considerable risk for infection and was therefore inappropriate in this boy, who had preoperative infection and inflammation.

Because of our considerable experience using TPFL for dorsal augmentation, we elected to use TPFL together with crushed septal cartilage to repair the dorsal defect of this patient. When TPFL is used for dorsal augmentation in rhinoplasty procedures, it can be easily cut into the desired shapes and multilayered. Thus, TPFL can provide sufficient thickness to camouflage the dorsum (11). Furthermore, the soft contour of TPFL enables it to be blended well with the overlying skin-soft tissue envelope. TPFL also has the advantage of a low infection rate, the absence of donor site morbidity, and minimal risk for displacement and extrusion. As in our patient, the sinus tract may be ruptured by severe inflammation, making it virtually impossible to completely remove the entire sinus tract. Thus, some remnant of the cystic lesion may remain postoperatively. Another potential benefit of TPFL is its ability to separate the remnant sinus tract from the dorsal skin, thus preventing recurrent skin infection. Unpredictable resorption of TPFL has been observed in 3 (4.3%) out of 69 patients reported in our previous study (11). However, the patient did not show loss of volume at the two-year follow-up.

The open rhinoplasty approach using TFPL can be a useful surgical option as illustrated by the patient presented here.

References

1. Hughes GB, Sharpino G, Hunt W, Tucker HM. Management of the congenital midline nasal mass: a review. Head Neck Surg. 1980; Jan–Feb. 2(3):222–233. PMID: 7353954.

2. Denoyelle F, Ducroz V, Roger G, Garabedian EN. Nasal dermoid sinus cysts in children. Laryngoscope. 1997; 6. 107(6):795–800. PMID: 9185736.

3. Blake WE, Chow CW, Holmes AD, Meara JG. Nasal dermoid sinus cysts: a retrospective review and discussion of investigation and management. Ann Plast Surg. 2006; 11. 57(5):535–540. PMID: 17060735.

4. Posnick JC, Bortoluzzi P, Armstrong DC, Drake JM. Intracranial nasal dermoid sinus cysts: computed tomographic scan findings and surgical results. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994; 4. 93(4):745–754. PMID: 8134433.

5. Rahbar R, Shah P, Mulliken JB, Robson CD, Perez-Atayde AR, Proctor MR, et al. The presentation and management of nasal dermoid: a 30-year experience. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003; 4. 129(4):464–471. PMID: 12707196.

6. Pollock RA. Surgical approaches to the nasal dermoid cyst. Ann Plast Surg. 1983; 6. 10(6):498–501. PMID: 6349506.

7. Morrissey MS, Bailey CM. External rhinoplasty approach for nasal dermoids in children. Ear Nose Throat J. 1991; 7. 70(7):445–449. PMID: 1914965.

8. Loke DK, Woolford TJ. Open septorhinoplasty approach for the excision of a dermoid cyst and sinus with primary dorsal reconstruction. J Laryngol Otol. 2001; 8. 115(8):657–659. PMID: 11535151.

9. Rohrich RJ, Lowe JB, Schwartz MR. The role of open rhinoplasty in the management of nasal dermoid cysts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999; 12. 104(7):2163–2170. PMID: 11149785.

10. Mankarious LA, Smith RJ. External rhinoplasty approach for extirpation and immediate reconstruction of congenital midline nasal dermoids. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1998; 9. 107(9 Pt 1):786–789. PMID: 9749549.

11. Jang YJ, Wang JH, Sinha V, Song HM, Lee BJ. Tutoplast-processed fascia lata for dorsal augmentation in rhinoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007; 7. 137(1):88–92. PMID: 17599572.

Fig. 2

Sagittal T1-weighted, gadolinium-enhanced MRI reveals the nasal dermoid sinus cyst on the nasal dorsum without intracranial extension.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download