Abstract

Spontaneous tonsillar hemorrhage from infectious causes is extremely rare and post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage, although also relatively rare, is an unavoidable complication of the procedure. Hemorrhage in association with tonsillitis or tonsillectomy is potentially dangerous and can be life threatening. We report here the presentation and management of a 42-yr-old man with severe spontaneous hemorrhage from infected tonsils and post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage. We suggest that if attempts to control the bleeding are not successful or if severe spontaneous tonsillar hemorrhage occurs repeatedly or a malignancy is suspected, tonsillectomy and close postoperative follow up is recommended.

Spontaneous tonsillar hemorrhage is a rare complication of acute or chronic tonsillitis, most likely due to the early use of antibiotics (1). It is reported that the incidence of significant hemorrhagic complications of infectious tonsillitis is about 1.1% (2). Infectious and inflammatory disease of the tonsil can lead to vessel erosion from a smaller peripheral tonsil vessel to a major vessel, such as the carotid artery. Spontaneous tonsillar bleeding from a smaller peripheral vessel can be successfully treated with local intervention or tonsillectomy. Post-tonsillectomy bleeding is a well-known complication of the procedure and has frequently been reported in the medical literature because this is a common procedure in otolaryngology practice. We present a case of repeated spontaneous tonsillar hemorrhage and post-operative bleeding following a tonsillectomy for management of recurrent spontaneous tonsillar hemorrhage.

A 42-yr-old man was referred to us by his local physician after a 1.5 hr episode of oral bleeding. His history was positive for a sore throat for 3 months that had been treated intermittently with antibiotics. There was no prior history of oral bleeding. An examination revealed bilateral tonsillar hypertrophy with hyperemia, and a blood clot in the lower pole of the right tonsil. However, no active bleeding was seen. The white blood cell count, hemoglobin, prothrombin/partial thromboplastin levels and bleeding time were normal. The blood clot was removed and the lower pole of the right tonsil was cauterized with silver nitrate. Oral antibiotics were prescribed and the patient was scheduled for a tonsillectomy.

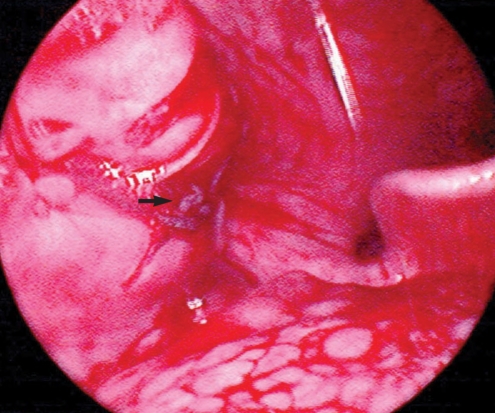

Seven days later the patient presented to the emergency room because of spitting fresh blood from the mouth for 1 hr. His tonsils were congested and fresh blood was seen oozing from the lower pole of the right tonsil (Fig. 1). His hemoglobin level fell from 14.9 g/dL to 11.2 g/dL. The patient was admitted to the hospital and an emergency tonsillectomy was performed.

On postoperative day 4, the patient presented to the emergency room with a history of bright red bleeding from the mouth for a few hours. His hemoglobin level was 6.9 g/dL and he received 2 units of packed red blood cells. In the operating room, diffuse oozing from the tonsillar beds was cauterized with bipolar diathermy hemostasis under general anesthesia. The hemoglobin level was 9.5 g/dL (post-transfusion). On postoperative day 9, the patient complained of fresh bleeding from the mouth. The bleeding was controlled by bipolar diathermy hemostasis under local anesthesia. The hemoglobin level was 6.7 g/dL and the patient received 2 units of packed red blood cells.

During hospitalization, further evaluations for a bleeding disorder were carried out. However, there was no clinical or laboratory evidence of a hematological or clotting disorder. On postoperative day 14, the patient was discharged from the hospital.

Spontaneous tonsillar hemorrhage is diagnosed due to the bleeding of intact tonsils after iatrogenic or prior surgical causes have been ruled out. Griffies et al. (2) defined spontaneous tonsillar hemorrhage as continuous bleeding for more than 1 hr or loss of more than 250 mL of blood regardless of the duration of bleeding. There are various pathologic conditions associated with spontaneous tonsillar hemorrhage, including acute or chronic tonsillitis, peritonsillar or parapharyngeal abscess, infectious mononucleosis, carotid aneurysm or pseudoaneurysm, tonsil cancer, etc (2). The most common cause of spontaneous tonsillar hemorrhage is bacterial or viral infection; it is rarely associated with a malignancy or coagulopathy (2, 3). Evaluation for bacterial tonsillitis, viral infection (including measles, infectious mononucleosis, and others), peritonsillar or other space occupying abscess, as well as cancer of the tonsils should be carried out (1-5).

A spontaneous tonsillar hemorrhage presents as bleeding or blood clots identified in the mouth. Therefore, hemoptysis, hematemesis, posterior epistaxis, carcinoma related to the naso- or hypopharynx and hematological and clotting disorders should be considered in the differential diagnosis of spontaneous tonsillar hemorrhage (6). A spontaneous tonsillar hemorrhage should be included in the differential diagnosis of hematemesis, hemoptysis and posterior epistaxis, similar to our patient (5).

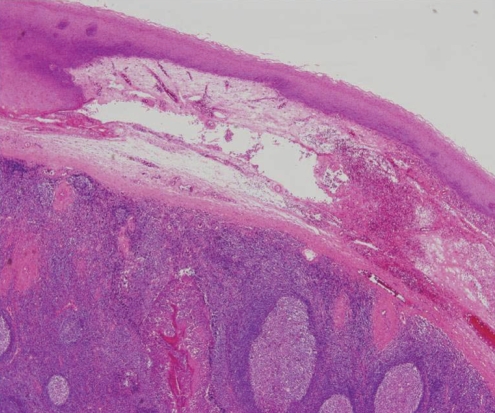

It is possible that inflammation of the tonsils results in increased blood flow to the tonsils and then necrosis or trauma of the congested tonsillar vessels leads to spontaneous tonsillar hemorrhage (3) (Fig. 2). The extravasation of red blood cells from the engorged tonsillar vasculature may lead to diffuse parenchymal bleeding (5).

The treatment of spontaneous tonsillar hemorrhage generally consists of local control with silver nitrate cauterization, epinephrine injection, suture ligation and unilateral or bilateral tonsillectomy (2, 3). In mild cases, conservative local control and/or antibiotic therapy is recommended. However, if local control of the bleeding is not successful, or severe spontaneous tonsillar hemorrhage occurs repeatedly, or a malignancy is suspected, tonsillectomy and close postoperative follow up is recommended. In this case, we immediately performed tonsillectomy for the following reasons: 1) recurrent history of spontaneous tonsillar hemorrhage, 2) the lack of response to local control using silver nitrate cauterization, and 3) the patient did not want conservative local control as management of repeated spontaneous tonsillar hemorrhage. This case illustrates a rare, but potentially life threatening complication of tonsillitis.

References

1. Shatz A. Spontaneous tonsillar bleeding; secondary to acute tonsillitis in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1993; 3. 26(2):181–184. PMID: 8444561.

2. Griffies WS, Wotowic PW, Wildes TO. Spontaneous tonsillar hemorrhage. Laryngoscope. 1988; 4. 98(4):365–368. PMID: 3352432.

3. Levy S, Brodsky L, Stanievich J. Hemorrhagic tonsillitis. Laryngoscope. 1989; 1. 99(1):15–18. PMID: 2909817.

4. John DG, Thomas PL, Semeraro D. Tonsillar haemorrhage and measles. J Laryngol Otol. 1988; 1. 102(1):64–66. PMID: 3343568.

5. Kumra V, Vastola AP, Keiserman S, Lucente FE. Spontaneous tonsillar hemorrhage. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001; 1. 124(1):51–52. PMID: 11228452.

6. Dawlatly EE, Satti MB, Bohliga LA. Spontaneous tonsillar hemorrhage: an underdiagnosed condition. J Otolaryngol. 1998; 10. 27(5):270–274. PMID: 9800625.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download