Abstract

Objectives

Vidian neurectomy could be considered the treatment of choice for intractable rhinitis, because it is the only method that can permanently block the pathophysiological mechanism of rhinitis. The goal of this study was to evaluate the effect of vidian neurectomy on nasal symptoms and tear production, and to assess for possible complications.

Methods

Six patients with intractable rhinitis who underwent endoscopic transnasal vidian neurectomy were enrolled. The degree of symptom improvement and complications were assessed through retrospective review of medical records prior to, and 1 year following surgery, and telephone survey after 6.9±2.1 years. Schirmer's test was performed before surgery, and these values were compared to postoperative results at 1 day, 1 month, and 2 months.

Results

Changes in the visual analogue scale were significant in nasal obstruction (8.5±2.5 to 3.0±2.0, P<0.05) and rhinorrhea (9.0±2.2 to 2.0±1.6, P<0.05). Improvements persisted for up to 7 years after the primary surgery. Patients complained of mild dry eyes for 1 month after vidian neurectomy. However, five out of six reported marked improvement of xerophthalmia after 2 months. Aside from mild crusting of the nasal cavity and mild postoperative pain, there were no major complications. During the entire follow-up period, no patient needed additional treatment, such as antihistamines or corticosteroids.

Treatment options for intractable rhinitis include antihistamines, topical or systemic corticosteroids, topical anticholinergics, laser or radiofrequency tissue volume reduction of turbinates, and subcutaneous or sublingual immunotherapy. However, some patients with intractable rhinitis often complain of persistent and severe nasal symptoms in spite of prolonged treatment. Because these patients often have difficulties living ordinary lives and coping with different social situations, they want definitive treatment for their discomfort without additional medications. In this respect, vidian neurectomy can be considered the treatment of choice, because it is the only method that can permanently block the pathophysiological mechanism of intractable rhinitis.

Golding-Wood (1) first introduced the concept of vidian neurectomy as definitive surgical management for vasomotor and allergic rhinitis in the 1960s. The theoretical basis of this surgery is an imbalance between parasympathetic and sympathetic innervation of the nasal cavity, and the resultant stimulation of goblet cells and mucous glands. The aim of this surgical technique is to disrupt this imbalance and reduce nasal secretions. However, many practitioners have abandoned vidian neurectomy due to technical difficulty, its transient effectiveness and reports of serious complications, such as visual loss (2).

However, in numerous previous studies, the vidian nerve was not definitely identified in the canal and sectioned under direct visualization (1, 2). Therefore, the transient effect of vidian neurectomy could have resulted from the placebo effect (3). The fact that many patients in previous studies did not complain of dry eyes implies that sectioning or cauterization of nerve fibers could have been insufficient, because xerophthalmia is inevitable the vidian nerve is sacrificed due to common innervations to the lacrimal gland (3, 4). With the advancement of endoscopic instrumentation and technique, identification and sectioning of the vidian nerve under direct visualization has become easier, resulting in fewer complications. Therefore, the effectiveness of vidian neurectomy needs to be re-evaluated.

The aims of this study were to evaluate the effectiveness of vidian neurectomy, by measuring symptom improvement and change in acoustic rhinometry parameters after surgery, the amount of tear production, and assess for possible complications.

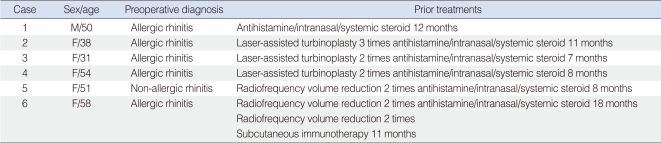

From January 2000 to July 2007, six patients diagnosed with allergic rhinitis (n=5) or non-allergic, non-infectious perennial rhinitis (n=1), and underwent endoscopic transnasal vidian neurectomy were enrolled. There was 1 male and 5 female patients with an age range of 31 to 58 years (mean, 47.0±9.0 years). The postoperative follow-up period was 3 to 10 years (mean, 6.9±2.1 years). All patients complained of severe nasal symptoms, such as nasal obstruction, rhinorrhea, sneezing, and itching. Conventional medications, such as antihistamines and inhaled or systemic corticosteroids for up to 18 months, and repeated surgical treatments, such as laser or radiofrequency tissue reduction of turbinates had been administered in these patients with minimal effectiveness, although patients were compliant to these regimens. Subcutaneous immunotherapy was used in one patient, who continued to complain of persistent nasal symptoms (Table 1). Because of severe nasal symptoms, patients had been feeling very uncomfortable during ordinary activities and social situations.

The vidian neurectomy procedure has been well described previously (3). In brief, patients lay in the reverse Trendelenburg position under general anesthesia. With the patient's head tilted to the right, surgical gauze soaked in epinephrine was used to shrink the middle turbinate sufficiently to improve visualization. If necessary, partial middle turbinectomy was performed. Infiltration anesthesia was performed to the posterior ends of the middle and superior turbinates with 2% xylocaine. The sphenopalatine foramen was identified at the posterior end (vanishing points) of the middle and superior turbinates as the point where vessels disappear. After making an incision with a sickle knife or elevator, dissection of the mucoperiostium was continued until the vidian canal was located posterolateral to the sphenopalatine foramen. The identified vidian nerve was coagulated by using bipolar cautery. Bone wax or gelfoam was packed to prevent nerve regeneration. The procedure was performed bilaterally. Five patients received bilateral vidian neurectomy, and 1 patient received bilateral radiofrequency volume reduction of the inferior turbinate in addition. The sphenopalatine artery was ruptured in one patient and bleeding was controlled using bipolar cauterization, with no postoperative bleeding.

Medical records before and up to 1 year after surgery were retrospectively reviewed, and telephone survey was conducted after about 7 years, to evaluate the degree of symptom improvement and assess for possible complications. Patients were asked to grade the severity of their nasal symptoms using a visual analogue scale (VAS). The VAS uses a 10-cm line with a dot at every centimeter, on which patients mark the severity of their symptoms from 0 to 10. On telephone surveys, the VAS system was explained and verbal responses were obtained. For more objective analysis, all patients received acoustic rhinometry before and after nasal provocation with house dust mite antigen (Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus) extracts, before and about 1 year (mean, 13.5±1.8 months) after surgery. The change in minimal cross-sectional area (MCA) after provocation was then compared. Possible complications, such as dry eyes, nasal crusting, visual disturbance, headache, facial pain, and numbness of palate, cheek, or teeth were also assessed by chart review or telephone survey. If a patient reported complications, the severity and need for additional treatment were asked. For dry eyes, Schirmer's test was performed before surgery and these values were compared to the postoperative results at 1 day, 1 month, and 2 months. All patients gave informed consent to the procedure and were informed of possible complications of vidian neurectomy and the purpose of this study. The study was approved by the Inha University Institutional Review Board committee.

Because of the small sample size and inclusion of non-parametric data, the Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare pre- and post-operative VAS scores. SPSS ver. 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis, and a P-value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

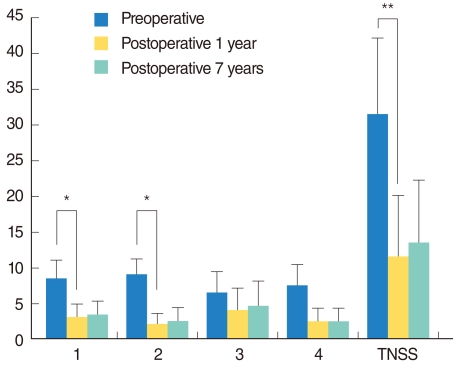

One year after vidian neurectomy (mean, 13.5±1.8 months), patient VAS scores were significantly lower than the preoperative values for nasal obstruction (3.0±2.0 vs. 8.5±2.5, P<0.05) and rhinorrhea (2.0±1.6 vs. 9.0±2.2, P<0.05) (Fig. 1). VAS scores were also lower but not statistically significant in sneezing (4.0±3.1 vs. 6.5±3.0) and itching (2.5±1.9 vs. 7.5±3.0) (Fig. 1). After 7 years, there were no significant increases in VAS scores compared to the 1-year scores (Fig. 1). Total nasal symptom score (TNSS) was defined as the sum of the VAS scores of all these symptoms. TNSS significantly decreased from 31.5±10.7 to 11.5±8.6 (P<0.01) at 1 year, and after 7 years there was no significant difference from the 1-year value. Change of MCA after surgery was significantly reduced compared with preoperative one (preoperative 45.0±9.9% vs. postoperative 17.1±7.1%, P<0.01).

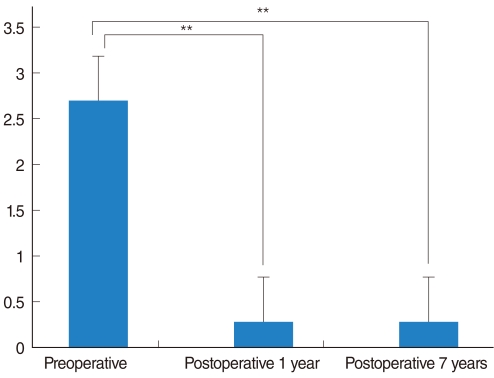

All patients complained of mild dry eyes in the immediate postoperative period. The results of Schirmer's test performed immediately after surgery were significantly decreased compared to preoperative values (4.6±2.2 mm vs. 14.5±3.7 mm, P<0.01). Complaints of mild dry eyes persisted for 1 month after vidian neurectomy, but after 2 months, 5 of 6 patients reported marked improvement of xerophthalmia. The amount of tears by the Schirmer's test was also increased (Fig. 2). There were no serious complications, aside from mild crusting of the nasal cavity and mild postoperative pain, which all subsided within 2 weeks. There were no cases of numbness of the palate or teeth, visual disturbance, or facial pain. Although one patient complained of mild numbness of the cheek after surgery, his symptoms improved after 1 week.

During the follow up period, no patient needed additional treatment, such as antihistamines or corticosteroids. All 6 patients were satisfied with the results of the surgery, although 1 patient reported mild deterioration of symptoms compared to the immediate postoperative period. When the authors set the medication score as: 0 for no medication needed, 1 for oral antihistamine, 2 for intranasal steroid, and 3 for systemic corticosteroid, the medication scores were significantly decreased following vidian neurectomy, in all patients, compared to their preoperative levels (Fig. 3).

In this study, there was a significant change in nasal obstruction and rhinorrhea VAS scores after vidian neurectomy. Changes in sneezing or itching were not statistically significant. These results are consistent with that of other studies. Robinson and Wormald (3) reported significant improvement of rhinorrhea and nasal obstruction but no significant change in sneezing or postnasal drip. Other reports also suggest that reduction in rhinorrhea is the main effect, and that improvement of nasal obstruction and sneezing is less obvious (2, 5, 6). In this study, the effects of vidian neurectomy sustained for 7 years or more after surgery. It was likely caused by interruption of cholinergic innervation to the nasal mucosa. Several changes, such as significant reduction of stromal edema and eosinophilic infiltration, reduction of mast cells and histamine, and reduction of mucosal gland acini content are visible after vidian neurectomy (3). These changes are thought to induce improvement in sneezing, nasal obstruction, and rhinorrhea.

Although Robinson and Wormald (3) suggested that assessment of tear production using the Schirmer's test would be needed in the future, no study has objectively evaluated the degree of dry eyes following vidian neurectomy. The incidence of postoperative dry eyes was 12 to 30% in several other reports (2, 5-7). Because both the nasal cavity and the lacrimal gland are innervated by the vidian nerve, all patients should experience dry eyes after vidian neurectomy if the correct resection of the nerve was performed. All patients in this study complained of dry eyes immediately after surgery, suggesting adequate blockade of parasympathetic innervation. The occurrence of dry eyes was objectively evaluated using the Schirmer's test. Two months after surgery, most patients reported markedly improved dry eyes. This improvement could be explained by the lack of satisfactory tests of lacrimal function, regeneration of lacrimal secretomotor fibers, and possible alternative preganglionic pathways.

Although serious complications such as visual loss have been reported, such severe complications could be avoided with better endoscopic visualization and good anatomical knowledge. One patient in this study complained of mild cheek numbness after the operation. Because the maxillary branch of trigeminal nerve within the foramen rotundum is close to the vidian foramen and is separated from it by only a small bony ridge, the maxillary nerve could have sustained thermal injury during cauterization of the vidian nerve. Another common complication of vidian neurectomy is bleeding from the sphenopalatine artery (4), which was seen in one patient in this study. The bleeding was well controlled with cauterization without other side effects.

Previous reports described vidian neurectomy using the transantral (1, 8), transnasal (2, 7, 9, 10), and transpalatal approaches (11). However, correct identification and adequate sectioning of the vidian nerve were not performed. Therefore, recurrence of symptoms and transient effectiveness of the surgery was inevitable (3). With adequate cauterization of the nerve under direct visualization, vidian neurectomy was very effective in alleviating symptoms in patients with intractable rhinitis. Robinson and Wormald (3) suggested that in order to prevent regeneration, it is essential to remove a segment of the nerve and cauterize the nerve stump. In this study, gelfoam or bone wax was placed between nerve stumps with excellent preventive effect.

Only patients with intractable rhinitis whose symptoms were refractory to medical or surgical treatment, and whose quality of life was significantly affected were enrolled in this study. The long-term effectiveness of vidian neurectomy was proven in these patients, suggesting that vidian neurectomy is the last, most definitive surgical option for patients with intractable rhinitis refractory to other management strategies.

The limitation of our study is that there is no control group to compare the effect of vidian neurectomy. However, because the authors only selected 'intractable' patients who were refractory to any other medication or surgical managements, it would be unethical to administer other therapy of questionable efficacy, only for statistical purposes.

The evaluation of postoperative symptom change was performed mainly by telephone survey. However, because all patients underwent routine outpatient follow-up for more than 1 year, and were well educated about the importance of medication history, the telephone survey was deemed reliable. By carefully asking the medication history after the surgery, the authors could rule out the confounding effect of other anti-allergic medications.

In conclusion, vidian neurectomy is effective in providing long-lasting alleviation of nasal symptoms, especially nasal obstruction and rhinorrhea, in patients with intractable rhinitis refractory to other therapy with minimal postoperative complications.

References

1. Golding-Wood PH. Observations on petrosal and vidian neurectomy in chronic vasomotor rhinitis. J Laryngol Otol. 1961; 3. 75(3):232–247. PMID: 13706533.

2. Fernandes CM. Bilateral transnasal vidian neurectomy in the management of chronic rhinitis. J Laryngol Otol. 1994; 7. 108(7):569–573. PMID: 7930892.

3. Robinson SR, Wormald PJ. Endoscopic vidian neurectomy. Am J Rhinol. 2006; Mar–Apr. 20(2):197–202. PMID: 16686388.

4. Lee JC, Hsu CH, Kao CH, Lin YS. Endoscopic intrasphenoidal vidian neurectomy: how we do it. Clin Otolaryngol. 2009; 12. 34(6):568–571. PMID: 20070769.

5. Jaradeh SS, Smith TL, Torrico L, Prieto TE, Loehrl TA, Darling RJ, et al. Autonomic nervous system evaluation of patients with vasomotor rhinitis. Laryngoscope. 2000; 11. 110(11):1828–1831. PMID: 11081594.

6. Banov CH, Lieberman P. Efficacy of azelastine nasal spray in the treatment of vasomotor (perennial nonallergic) rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2001; 1. 86(1):28–35. PMID: 11206234.

7. Kamel R, Zaher S. Endoscopic transnasal vidian neurectomy. Laryngoscope. 1991; 3. 101(3):316–319. PMID: 2000022.

8. Rose KG, Ortmann R, Wustrow F, Seegers D. Vidian neurectomy: neuroanatomical considerations and a report on a new surgical approach. Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1979; 224(3-4):157–168. PMID: 526181.

9. Iguchi Y, Yao K, Okamoto M. A characteristic protein in nasal discharge differentiating non-allergic chronic rhinosinusitis from allergic rhinitis. Rhinology. 2002; 3. 40(1):13–17. PMID: 12012948.

10. Konno A, Togawa K. Vidian neurectomy for allergic rhinitis. Evaluation of long-term results and some problems concerning operative therapy. Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1979; 225(1):67–77. PMID: 556246.

11. Krajina Z. Critical review of Vidian neurectomy. Rhinology. 1989; 12. 27(4):271–276. PMID: 2696076.

Fig. 1

The mean visual analogue scale (VAS) of nasal symptoms pre-surgery, 1 year, and 7 years after vidian neurectomy. 1, nasal obstruction; 2, rhinorrhea; 3, sneezing; and 4, itching. (Wilcoxon signed rank test, *P<0.05, **P<0.01). TNSS: total nasal symptom

score.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download