The pathogenesis of osteoradionecrosis was first described by Ewing in 1926 (

4). The first case of osteoradionecrosis of the temporal bone was reported by Block in a patient with syringobulba in 1952 (

5). An aseptic, avascular necrosis of the bony tissue with obliterative vasculitis and arteritis is the main pathogenesis, and this is more likely to occur in the presence of tumor involvement. As osteolysis proceeds, demineralization of the bone with a compensatory reparative fibrosis occurs in the absence of osteoblastic activity. The tissue then becomes prone to injury and highly susceptible to infection. After infection sets in, the necrotic process accelerates and osteoradionecrosis continues. The severity of necrosis is closely correlated to the total amount of radiation. In this case, the recurrent tumor was closely approximated with temporal bone, possibly increasing the exposure to a relatively high dose of radiation. Osteoradionecrosis of the temporal bone was classified as either a localized or diffuse type by Ramsden et al. (

1). In the localized type, osteoradionecrosis is generally confined to the external auditory canal, and symptoms usually include dermatitis, otalgia, and otorrhea. In the diffuse type, the disease extends beyond the temporal bone to the skull base. This type of disease can produce more severe symptoms including profuse and pulsatile otorrhea, and significant pain and can also be a more severe complication (

2). Osteoradionecrosis of the temporal bone can make complications like hearing loss, gross tissue extrusion, chronic otomastoiditis, as well as more severe complications including meningitis, facial palsy, intradural and/or extradural abscesses, pneumocephalus, lateral sinus thrombosis, fistula formation into the parotid gland or temporal mandibular joint, and other cranial neuropathies (

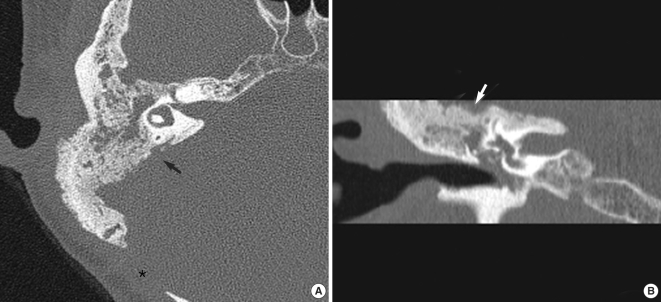

6). In this patient, the disease was relatively diffuse involving mostly the mastoid bone but not the deep skull base. The patient presented with an exceptionally rare complication of osteoradionecrosis of the temporal bone, secondary to radiotherapy for meningioma: an otogenic CSF leak. In this case, β

2-transferrin was identified and a dry glucose test of the collected discharge suggested it could be CSF, although an isotope cisternogram study could not find the leakage site. This patient had a tympanic membrane perforation. However, considering the lack of otologic problems before radiotherapy, the perforation could have been caused by radionecrosis and/or subsequent infection. The patient was first treated conservatively with antibiotics and aural cleansing, but long-lasting clear aural fluid despite conservative treatment implied that it was a CSF leak. On the other hand, it is conceivable that recurrent meningioma may destroy the temporal bone resulting in CSF leakage. In this case, preoperative CT imaging study did not show a destructive pattern of the temporal bone but rather typical hyperostosis with sclerotic and lytic changes and small mastoid tegmen defect which was detected in operation might be caused by lytic change.

The management of osteoradionecrosis in the temporal bone is controversial. In the localized type, conservative treatment with frequent aural cleansing and topical antibiotics is often administered (

7). In the presence of CSF leakage, conservative management such as bed rest, head elevation and, insertion of a subarachnoid drain can be useful. But for an unresponding case or the diffuse type, surgical management is indicated. Surgical management of osteoradionecrosis of the temporal bone has met with limited success because of the difficulty of accurate assessment of the viability of non-necrotic bone. Failure to resect all non-viable bone results in recurrence of a necrotic focus (

8). In this case, we removed all inflamed, sponge-like non-viable bone that corresponded to the radionecrosis and closed the defect with autologous abdominal fat.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download