Abstract

Background

Acute postoperative pain control in children is an essential component of postoperative care, particularly in daycare procedures. Giving patients continuous narcotic analgesics can be risky; however, a single dose may be sufficient.

Methods

This study used a prospective, randomized controlled design and was conducted at the Pediatric Surgery Unit, Services Hospital, Lahore. In total, 150 patients who underwent inguinal herniotomy (age range: 1–12 years) were randomly assigned to two groups: group A (nalbuphine) and group B (tramadol). Patients were given a single dose of either nalbuphine (0.2 mg/kg) or tramadol (2 mg/kg) immediately after surgery and pain was measured at 0, 1, 2, 4, and 8 h.

Results

The demographic characteristics were similar between the two groups. The mean pain score was lower in group A than in group B at 0 and 1 h (P < 0.05). However, at 4 h and 8 h, the pain scores in group A were still lower, but not significantly. In all, 9 patients (12.0%) required rescue analgesics in group A compared to 16 patients (21.3%) in group B (P = 0.051). The mean time for requirement of rescue analgesics was 6.5 ± 0.5 h in group A and 5.3 ± 1.7 h in group B (P = 0.06).

Go to :

Pain is an important and complex protective phenomenon. Good postoperative pain relief is important as it alleviates patient distress and aids a rapid, uncomplicated recovery [1]. Inguinal hernia and hydrocele, which are common problems in children, are frequently treated by herniotomy.

Unfortunately, the number of analgesic agents available for postoperative use in pediatric populations is very limited, particularly when a patient has “nothing per oral” status. Narcotic analgesics are a mainstay in pediatric surgery in this context. Nalbuphine is a semi-synthetic opioid analgesic that belongs to the phenanthrene family. It is commonly used for pain management in children, but is associated with certain side effects such as respiratory and central nervous system depression, emesis, and pruritus due to its effect on µ2 receptors [2]. These side effects require intense postoperative care and vigilant nursing.

Tramadol is a potent analgesic that binds to µ1 and µ2 receptors and enhances the inhibitory action of descending pain pathways. In contrast to other opioids, including nalbuphine, tramadol does not induce tolerance and is associated with reduced adverse effects [34]. In a previous study, nalbuphine was compared to tramadol, and patients in the nalbuphine group required more rescue analgesic doses (3/12; 25%) compared to the tramadol group (1/12; 8.3%) [5].

Therefore, in this study, we compared the efficacy of nalbuphine and tramadol for the management of postoperative pain in children after inguinal herniotomy.

Go to :

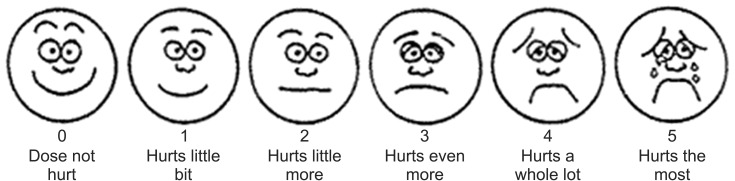

After obtaining approval from our hospital's ethics committee, we conducted a randomized, controlled trial at the Pediatric Surgery Unit of Services Hospital, Lahore, Pakistan, between January 2014 and December 2014. A sample size of 150 cases (n = 75 in each group) was required for 80% statistical power at a 5% level of significance, taking the expected proportions of patients undergoing inguinal herniotomy requiring rescue analgesics to be 25% in the nalbuphine group and 8.3% in the tramadol group [5]. We included all elective inguinal hernia and hydrocele patients (American Society of Anesthesiologists [ASA] class I and II) aged between 1 and 12 years. We excluded patients who were already on analgesics, had an obstructed inguinal hernia, ASA grade ≥ 3, or any sort of respiratory, cardiovascular, or neurological disorder. For measurement of pain, Wong-Baker Faces pain scale was used after getting permission from Wong-Baker Faces foundation.

All patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria were included in the study. They were divided into two groups using the lottery method: group A, nalbuphine; and group B, tramadol. Informed consent was obtained from each patient and the parents/guardians of the patients were assured confidentiality of the data and the expertise of the surgeons carrying out the procedure. They were also informed about our expectation of achieving a positive outcome.

All of the patients were drawn from the elective list of the pediatric surgical team of our hospital, and they were all administered standard anesthetics including midazolam (0.05 mg/kg), ketorolac (0.5 mg/kg), and propofol (1.5–2.0 mg/kg) for induction. Suxamethonium chloride (1.0 mg/kg) was used to facilitate endotracheal intubation. Maintenance of anesthesia was accomplished with low-flow oxygen (0.5–1.0 L/min) plus 0.7–1.5% isoflurane. In addition, atracurium (0.5 mg/kg as a bolus dose) was administered and repeated at 0.1 mg/kg if required to facilitate artificial ventilation. The parameters monitored during the procedure included heart rate (using a three-lead electrocardiograph), respiratory rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, mean arterial pressure, and fingertip pulse oximetry. Isoflurane was stopped approximately 5 min before the end of surgery and replaced with 100% oxygen. Neuromuscular blockade was reversed with neostigmine and atropine and the patients were extubated according to the standard train-of-four criteria.

Either nalbuphine (0.2 mg/kg) or tramadol (2 mg/kg) was given to patients just after arrival at the recovery room. Patients were assessed with respect to postoperative pain intensity using the Wong-Baker Faces Pain Scale (Fig. 1) at 0, 1, 2, 4, 6 and 8 h after surgery, by an on-duty doctor who was unaware of the drugs given to patients. Patients with pain scores ≥ 4 were given paracetamol (10 mg/kg), which was then recorded. Furthermore, any side effects (vomiting, respiratory depression, or pruritus) were noted and recorded. After 8 h of surgery, patients were given oral ibuprofen (10 mg/kg) and were discharged after being assessed by a senior, on-duty team member.

All of the data were analyzed using the SPSS for Windows software package (version 21.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Simple descriptive statistics were obtained, with mean ± SD calculated for numerical values such as age and pain score (using the Wong-Baker Faces Pain Scale). Frequencies and percentages were calculated for qualitative variables, such as sex and the proportion of patients requiring rescue analgesics in both groups, using the chi-square test. A P value ≤ 0.05 was taken to indicate statistical significance.

Go to :

A total of 150 patients fulfilling the inclusion and exclusion criteria were included in the study. Demographic characteristics, including age, gender, and site of inguinal hernia, were similar between the groups (Table 1).

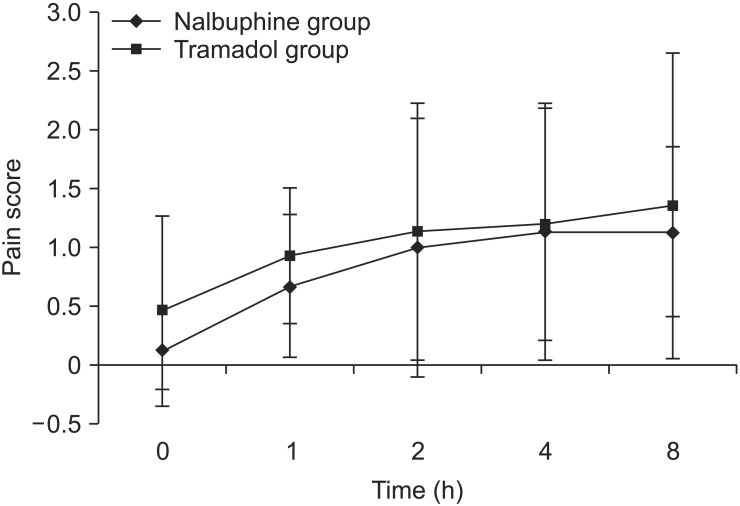

Pain scores were noted at 0, 1, 2, 4, and 8 h (Fig. 2). There was a significant difference between groups in pain scores at 0 and 1 h (both P < 0.05), but not at 2, 4, or 8 h.

In all, 9 patients (12.0%) needed rescue analgesics in group A compared to 16 patients (21.3%) in group B (P = 0.051). The mean time for requirement of rescue analgesics was 6.5 ± 0.5 h in group A and 5.3 ± 1.7 h in group B (P = 0.06). Side effects were noted in both groups, of which the most common was vomiting (group A: n = 9, 12.0%; group B: n = 10, 13.3%). No other side effects were noted in either group.

Go to :

Postoperative pain in children is an important, but significantly understudied, condition. The reported rate of moderate to severe acute post-surgical pain (APSP) in children is 15–60% [6]. Numerous options for APSP management are being introduced. Different trials have compared narcotic analgesics, local infiltration of different agents, and caudal and regional blocks [7].

For APSP management, narcotic analgesics are most commonly used, particularly for major surgery in children. However, for daycare pediatric surgery, alternative agents are currently being tried. One of these agents is tramadol, a synthetic, centrally acting opioid analgesic that is associated with reduced respiratory depression compared to other opioids [8]. In a pilot study, Moyao-García et al. [5] found that tramadol was significantly better than nalbuphine for the management of APSP in children after inguinal herniotomy. In our study, we provided patients with only a single dose of either of these drugs, as our patients routinely undergo herniotomy as a daycare procedure.

Pain assessment in children is difficult, although many tools and assessment charts are available. Assessment is particularly difficult in children younger than 1 year of age [9]. To avoid the complications associated with using two or more tools, and to eliminate bias, we included patients ≥ 1 year of age, such that universal assessment of APSP could be achieved.

Pain scores were obtained at different time points and then compared between the two groups. Although no significant differences were noted, the scores were higher in the tramadol group than in the nalbuphine group. These findings contradict our reference study [5], in which tramadol was superior to nalbuphine. Similarly, the number of patients requiring rescue analgesics was greater in the tramadol group than in the nalbuphine group, also contradicting the reference study. Van Den Berg et al. [10] compared the effects of tramadol and nalbuphine in children and reported that the nalbuphine-treated patients had better analgesia, during both the procedure and the postoperative period.

In our study, 9 patients (12%) in group A required rescue analgesics, compared to 16 (21.3%) in group B (P = 0.06). Barsoum [11] conducted a trial that compared the effects of tramadol, nalbuphine, and pethidine in children and found that tramadol was superior to nalbuphine. In that trial, 40% of patients in the nalbuphine group required two or more analgesic doses, compared to 4% of patients in the tramadol group. This result contrasts with our study, probably due to differences in study design: Barsoum used an open trial design in which the same drug was administered repeatedly as a rescue analgesic and as the initial dose.

The mean time for requirement of rescue analgesics was similar in both groups in our study. Usyal et al. [12] compared intravenous paracetamol and tramadol for APSP in children and found that the mean time for requirement of rescue analgesics was greater in the paracetamol group. However, the drugs in our study were of the same class, and both had half-lives of 6–8 h; therefore, the time for requirement of rescue analgesics was similar in both groups [13].

A study that used oral tramadol in children demonstrated a dose-ranging effect, where patients who received a 2 mg/kg dose required 42% less rescue analgesics than those who received a 1 mg/kg dose [14]. The most common side effects with tramadol use were postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) (9–10%), pruritus (7%), and rash (4%); these effects were observed more frequently with postoperative oral administration than with intraoperative use. In our study, the incidence of PONV was almost the same with both tramadol and nalbuphine. However, we observed no other side effects.

Schäffer et al. [15] conducted a meta-analysis and found only four studies that had compared nalbuphine and tramadol, all of which provided low-quality evidence for various reasons [5101116]. We have come across no subsequent studies that have compared these two drugs.

A limitation of our study was the fact that postoperative pain was measured up to 8 h only, whereas the majority of previous studies measured pain for up to 24 h postoperatively. Our results also contradict previous studies in terms of both the pain scores and the number of patients requiring rescue analgesia. Therefore, further trials with larger samples are needed for clarification. We also suggest that a single dose of pain killer medication in children who undergo daycare surgery should be sufficient, and furthermore that intravenous nalbuphine is superior to tramadol.

Go to :

References

1. Akhtar MI, Saleem M, Zaheer J. Wound infiltration with Bupivacaine versus Ketorolac for postoperative pain relief in minor to moderate surgeries. J Pak Med Assoc. 2009; 59:385–388. PMID: 19534374.

2. Bressolle F, Khier S, Rochette A, Kinowski JM, Dadure C, Capdevila X. Population pharmacokinetics of nalbuphine after surgery in children. Br J Anaesth. 2011; 106:558–565. PMID: 21310722.

3. Yenigun A, Et T, Aytac S, Olcay B. Comparison of different administration of ketamine and intravenous tramadol hydrochloride for postoperative pain relief and sedation after pediatric tonsillectomy. J Craniofac Surg. 2015; 26:e21–e24. PMID: 25569408.

4. Demiraran Y, Ilce Z, Kocaman B, Bozkurt P. Does tramadol wound infiltration offer an advantage over bupivacaine for postoperative analgesia in children following herniotomy? Paediatr Anaesth. 2006; 16:1047–1050. PMID: 16972834.

5. Moyao-García D, Hernández-Palacios JC, Ramírez-Mora JC, Nava-Ocampo AA. A pilot study of nalbuphine versus tramadol administered through continuous intravenous infusion for postoperative pain control in children. Acta Biomed. 2009; 80:124–130. PMID: 19848049.

6. Pagé MG, Stinson J, Campbell F, Isaac L, Katz J. Pain-related psychological correlates of pediatric acute post-surgical pain. J Pain Res. 2012; 5:547–558. PMID: 23204864.

7. Akkaya T, Bedirli N, Ceylan T, Matkap E, Gulen G, Elverici O, et al. Comparison of intravenous and peritonsillar infiltration of tramadol for postoperative pain relief in children following adenotonsillectomy. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2009; 26:333–337. PMID: 19401664.

8. Wang F, Shen X, Xu S, Liu Y. Preoperative tramadol combined with postoperative small-dose tramadol infusion after total abdominal hysterectomy: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Pharmacol Rep. 2009; 61:1198–1205. PMID: 20081257.

9. Salgado Filho MF, Gonçalves HB, Pimentel Filho LH, Rodrigues Dda S, da Silva IP, Avarese de Figueiredo A, et al. Assessment of pain and hemodynamic response in older children undergoing circumcision: comparison of eutectic lidocaine/prilocaine cream and dorsal penile nerve block. J Pediatr Urol. 2013; 9:638–642. PMID: 22897985.

10. van den Berg AA, Montoya-Pelaez LF, Halliday EM, Hassan I, Baloch MS. Analgesia for adenotonsillectomy in children and young adults: a comparison of tramadol, pethidine and nalbuphine. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 1999; 16:186–194. PMID: 10225169.

11. Barsoum MW. Comparison of the efficacy and tolerability of tramadol, pethidine and nalbuphine in children with postoperative pain. Clin Drug Investig. 1995; 9:183–190.

12. Uysal HY, Takmaz SA, Yaman F, Baltaci B, Başar H. The efficacy of intravenous paracetamol versus tramadol for postoperative analgesia after adenotonsillectomy in children. J Clin Anesth. 2011; 23:53–57. PMID: 21296248.

13. Xu J, Zhang XC, Lv XQ, Xu YY, Wang GX, Jiang B, et al. Effect of the cytochrome P450 2D6*10 genotype on the pharmacokinetics of tramadol in post-operative patients. Pharmazie. 2014; 69:138–141. PMID: 24640604.

14. Verghese ST, Hannallah RS. Acute pain management in children. J Pain Res. 2010; 3:105–123. PMID: 21197314.

15. Schäffer J, Piepenbrock S, Kretz FJ, Schönfeld C. Nalbuphine and tramadol for the control of postoperative pain in children. Anaesthesist. 1986; 35:408–413. PMID: 3092699.

16. Schnabel A, Reichl SU, Zahn PK, Pogatzki-Zahn E. Nalbuphine for postoperative pain treatment in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014; (7):CD009583. PMID: 25079857.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download