Abstract

Background

A nasogastric tube (NGT) is commonly inserted into patients undergoing abdominal surgery to decompress the stomach during or after surgery. However, for anatomic reasons, the insertion of NGTs into anesthetized and intubated patients may be challenging. We hypothesized that the use of a tube exchanger for NGT insertion could increase the success rate and reduce complications.

Methods

One hundred adult patients, aged 20–70 years, who were scheduled for gastrointestinal surgeries with general anesthesia and NGT insertion were enrolled in our study. The patients were randomly allocated to the tube-exchanger group or the control group. The number of attempts, the time required for successful NGT insertion, and the complications were noted for each patient.

Results

In the tube-exchanger group, the success rate of NGT insertion on the first attempt was 92%, which is significantly higher than 68%, the rate in the control group (P = 0.007). The time required for successful NGT insertion in the tube-exchanger group was 18.5 ± 8.2 seconds, which is significantly shorter than the control group, 75.1 ± 9.8 seconds (P < 0.001). Complications such as laryngeal bleeding and the kinking and knotting of the NGT occurred less often in the tube-exchanger group.

Conclusions

There were many advantages in using a tube-exchanger as a guide to inserting NGTs in anesthetized and intubated patients. Compared to the conventional technique, the use of a tube-exchanger resulted in a higher the success rate of insertion on the first attempt, a shorter procedure time, and fewer complications.

A nasogastric tube (NGT) is commonly inserted into patients undergoing abdominal surgery to decompress the stomach intraoperatively and postoperatively, prevent postoperative mechanical ileus, administer drugs, allow postoperative feeding, and facilitate gastric lavage. Inserting an NGT into an anesthetized and intubated patient may be difficult for anatomic reasons; the failure rate of NGT insertion on the first attempt with the head in the neutral position is up to 50% [1]. During insertion, the NGT is warmed by body heat and becomes even more vulnerable to coiling, kinking, and knotting. Thus, NGT insertion becomes more difficult on subsequent attempts and can become impossible. Furthermore, repeated trials could induce several complications such as nasal mucosal bleeding, pharyngeal bleeding, hypertension, tachycardia, and arrhythmia [2]. At the time of this writing, a variety of ways to reduce complications and the failure rate for insertion have been performed; these include the use of a slit endotracheal tube, forward displacement of the larynx, the use of various forceps, the use of a ureteral guidewire as a stylet, head flexion, lateral neck pressure, and the use of a gloved finger to steer the NGT after impaction [3456].

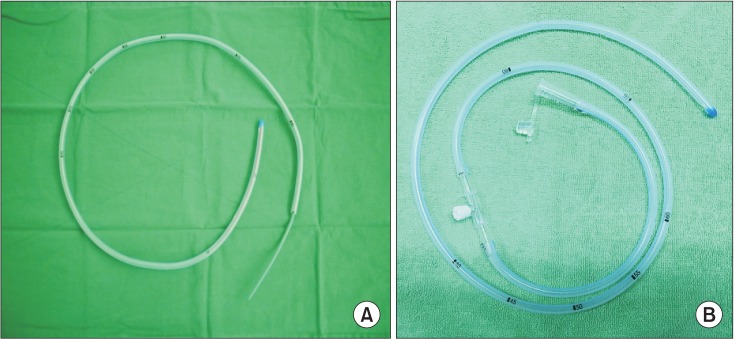

A tube exchanger (G36402, Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA) is a long, flexible, hollow tube. It is designed mainly to facilitate the exchange of gases in endotracheal tubes; additionally, it can be used for intratracheal oxygen insufflations, jet ventilation, and the measurement of end tidal CO2. A tube exchanger has a stiff body and a flexible blind tip; thus, we hypothesized that tube exchanger could make NGT insertion easy and safe.

In the current study, we first examined whether the success rate of NGT insertion on the first attempt would be higher with the use of a tube exchanger than with the conventional technique. We then examined whether the use of a tube exchanger might decrease possible complications associated with NGT insertion.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB: PNUYH03-2013-002) and the United States National Institutes of Health Clinical Trials Registry (NCT01783366). It was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

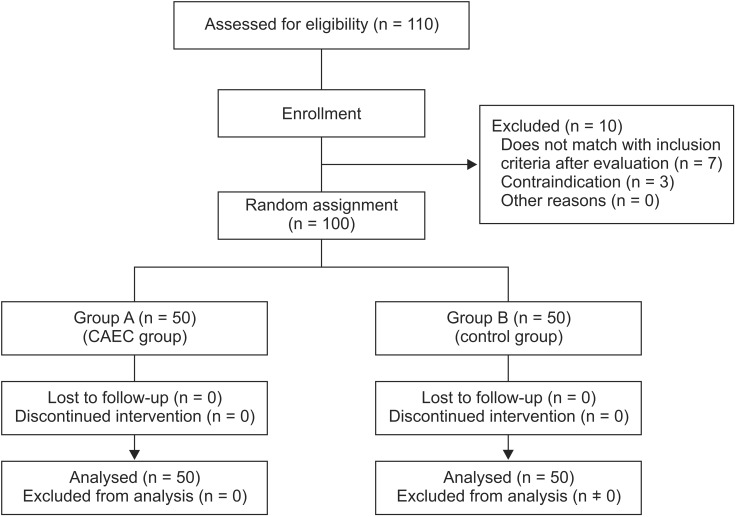

After signed informed consent was obtained from the patients, 100 adults who met these criteria were enrolled: (1) They were between the ages of 20 and 70 years old; (2) Their American Society of Anesthesiologists physical statuses were I or II; and (3) They were scheduled to undergo elective surgery of the gastrointestinal tract with NGT insertion under general anesthesia (Fig. 1). Patients with maxillofacial trauma, an inability to adequately protect the airway, or esophageal abnormalities were excluded. Pregnant patients were also excluded from the study.

All patients received general anesthesia. Glycopyrrolate (10 µg/kg) was injected 30 minutes before the induction of anesthesia. After patients were preoxygenated with 100% oxygen for 3 minutes, they received anesthesia via intravenous (IV) thiopental (3–5 mg/kg) and IV rocuronium (0.6 mg/kg). When the train of four reached 0 and the bispectral index value was 40–50, endotracheal intubation was performed. An NGT tube prepared with a tube exchanger was inserted into each patient through a nostril while the head was in the neutral position. Enrolled patients were randomly allocated to 1 of 2 groups. In the tube-exchanger group, a tube exchange catheter was used; in the control group, no equipment was used. For NGT insertion, a Levin tube (Yushin Medical Co., Bucheon, Korea) that was 20 Fr (inner diameter 4.4 mm, outer diameter 7.3 mm) and 127 cm long was used. For the tube-exchanger group, the Levin tubes were cut to be 90 cm in length. Then, a soft, flex-tipped tube exchanger that was 14 Fr and 100 cm long (Cook Airway Exchange Catheter, G36402, Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA) was lubricated with surgical lubricant (Surg-Jelle, Bio Chem Laboratories Corp., Gardena, CA, USA) and inserted into the NGT until the tip of the tube exchanger reached the tip of the NGT (Fig. 2A). The NGT tube was then inserted into the patient through a nostril while the patient's head was in the neutral position. In the control group, the same procedure was used except that the Levin tube was only lubricated; a tube exchanger was not inserted. The NGT insertion time was recorded as the time between the insertion of the NGT into a patient's nostril until the time at which 70 cm of the tube had been inserted. The NGT was then connected to a connector straight (Connector straight, Gish Biomedical Inc, CA, USA) and reconnected with previously cut portion (Fig. 2B). After 10 ml of air was injected through the NGT, insertion was considered successful if gurgling sounds were heard during auscultation over the epigastrium and gastric contents were aspirated. The total number of attempts until successful insertion was recorded. After the third unsuccessful trial, the case was considered a failure. After insertion, a laryngoscope was used to assess bleeding of the pharynx and the knotting and kinking of the NGT.

The calculation of the sample size was based on the following. The success rate of NGT insertion on the first attempt by using the conventional technique was approximately 50% in a published report [7], and we assumed that improvement of the success rate on the first attempt would be over 30% with the use of a tube exchanger. In each group, 50 experimental subjects were enrolled with the assumption that 10% might drop out (with a power of 0.80). The type I error associated with the test of this null hypothesis is 0.05.

Age, weight, height, and NGT insertion time were analyzed by using an unpaired t-test. The chi-square test was used to compare sex, number of trials, and complications during NGT insertion. The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. All analyses were performed by using StatView version 5.0 (SAS, Chicago, IL, USA) and MedCalc® Software (10.0, Mariakerke, Belgium).

A total of 100 patients (50 in each group) were included in this study. There were no statistically significant differences in the demographic data such as age, sex, height, and weight (Table 1). In the tube-exchanger group, insertion was successful in all patients: the NGT was successfully inserted in 92% of the patients on the first attempt and in 4 patients (8%) on the second attempt. In the control group, 68% of patients had an NGT placed successfully on the first attempt and 12 patients, on the second attempt. NGT insertion failed in 4 patients. The number of attempts was significantly lower in the tube-exchanger group (P = 0.007). The mean time required for successful NGT insertion was 18.5 ± 8.2 seconds in the tube-exchanger group; it was significantly shorter than time in the control group, 75.1 ± 9.8 seconds (P < 0.001, Table 2).

The occurrence of complications such as the bleeding of pharynx and the kinking and knotting of the NGT was significantly lower in the tube-exchanger group than in the control group. Pharyngeal bleeding occurred in 1 patient in the tube-exchanger group and in 9 patients in the control group (P = 0.020, Table 2). Kinking or knotting occurred in 10 patients in the control group but in none of the patients in the tube-exchanger group (P = 0.003, Table 2).

Compared to the conventional technique, the use of a tube exchanger resulted in a shorter procedure and a higher success rate of insertion on the first attempt. Moreover, the use of a tube exchanger could decrease the rate of complications caused by repeated attempts to insert NGTs in intubated patients.

For NGT insertion, the most commonly used methods are blind nasal insertion with external laryngeal manipulation and laryngoscope-guided insertion with Magill forceps [8]. Ozer and Benumof [6] found the pyriform sinuses and arytenoid cartilages were the most common sites of impaction during NGT insertion, whereas other investigators suggested that failures may be caused by the endotracheal tube itself, the base of the patient's tongue, or the cuff of the endotracheal tube bulging back onto the esophagus [9]. The average failure rate is 50% for blind insertion of an NGT on the first attempt with patient's head in the neutral position [1]; this is because the NGT is soft and made of flexible materials. Repeated attempts can make the NGT softer because of the patient's body heat, and, hence, make insertion more difficult and increase the risk of coiling, kinking, or knotting. Furthermore, the occurrence of complications, such as nasal mucosal bleeding, laryngeal bleeding, hypertension, tachycardia, and arrhythmia, may increase [2].

Various methods have been suggested to increase the success rate of NGT insertion. Some reports suggest that head flexion with lateral neck pressure is more effective in passing the NGT through the lateral or posterior hypopharynx [6]. Other methods of increasing the success rate include the use of a slit endotracheal tube placed via the nasoesophageal route [5], the use of a laryngoscope with Magill forceps [8], and gloved-finger steering to navigate the NGT [3]. Some reports suggest that NGT flexibility is significantly affected by NGT insertion [3810111213]. These methods have been introduced to harden the NGT: the ice-water method [9], placing the NGT in a refrigerator [4], the air or water-filled method [1011], freezing with distilled water [12], and using a large-caliber NGT [13]. Others methods include using a hard substance, such as a guidewire, inside the NGT to increase stiffness [5]. However, these methods have many limitations, introduce other complications, and require a long time for successful NGT insertion. Mucosal bleeding may be caused by using a slit endotracheal tube [5]. Aspiration and regurgitation are the risks of using the water-filled method [11] or freezing the NGT with distilled water [12]. Bradycardia and high peak airway pressure can be caused by the vasovagal response to compression of the bilateral carotid arteries [13] or the endotracheal tube being folded by forward neck flexion.

In our study, the rate of successful NGT insertion on the first attempt was higher in the tube-exchanger group (90%) than in the control group (68%). The NGT insertion time was significantly shorter in the tube-exchanger group than in the control group. Moreover, the tube-exchanger patients had fewer complications related to repeated attempts than did the control patients (Table 2). Accordingly, we conclude that for the first attempt at NGT insertion, the procedure time is shorter and the complication rate is lower. Thus, we suggest that the use of a tube exchanger for the blind insertion of an NGT is safer and results in fewer complications.

We assumed that because the tube exchanger had a flexible tip, using a larger caliber NGT than had been used in previous studies would result in a higher rate of successful first-attempt insertions and a lower rate of complications Hence, we used a 20-Fr NGT, which is larger than the 14-FR NGT that had been used in previous studies. The success rate of first-attempt insertions in the control group increased to 68% from 50%, the rate in the other study. In addition, in our study, pharyngeal bleeding in the tube-exchanger group (4%) occurred much less often than previously reported (11.3%) [2].

There are several limitations to our study. First, we used catheters from only 1 company, Cook Medical. In future studies, our procedures should be applied with catheters from other companies. Second, it is inconvenient to cut and reconnect the tube. However, because the technique has a high success rate and results in few complications, the inconvenience may be worthwhile. Furthermore, the required pieces of equipment – scissors and a connector – are easily available in the operating room.

In conclusion, the success rate of NGT insertion in anesthetized and intubated patients can be increased by using a catheter as a stylet. With a catheter, the time required for NGT insertion was shorter, and complications such as kinking and bleeding occurred less often. Overall, considering the success rate, the time required for insertion, and the complication rate, we conclude that the use of a catheter during NGT insertion is a simple, effective technique that has a higher success rate and lower complication rate than the conventional technique.

Acknowledgments

This study was registered ClinicalTrials.gov as NCT01783366.

This work was supported by 2 year research grant of Pusan National University.

References

1. Bong CL, Macachor JD, Hwang NC. Insertion of the nasogastric tube made easy. Anesthesiology. 2004; 101:266. PMID: 15220819.

2. Tsai YF, Luo CF, Illias A, Lin CC, Yu HP. Nasogastric tube insertion in anesthetized and intubated patients: a new and reliable method. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012; 12:99. PMID: 22853453.

3. Mahajan R, Gupta R. Another method to assist nasogastric tube insertion. Can J Anaesth. 2005; 52:652–653.

5. Appukutty J, Shroff PP. Nasogastric tube insertion using different techniques in anesthetized patients: a prospective, randomized study. Anesth Analg. 2009; 109:832–835. PMID: 19690254.

6. Ozer S, Benumof JL. Oro- and nasogastric tube passage in intubated patients: fiberoptic description of where they go at the laryngeal level and how to make them enter the esophagus. Anesthesiology. 1999; 91:137–143. PMID: 10422939.

7. Chun DH, Kim NY, Shin YS, Kim SH. A randomized, clinical trial of frozen versus standard nasogastric tube placement. World J Surg. 2009; 33:1789–1792. PMID: 19626360.

8. Kirtania J, Ghose T, Garai D, Ray S. Esophageal guidewire-assisted nasogastric tube insertion in anesthetized and intubated patients: a prospective randomized controlled study. Anesth Analg. 2012; 114:343–348. PMID: 22104075.

9. Tucker A, Lewis J. Procedures in practice. Passing a nasogastric tube. Br Med J. 1980; 281:1128–1129. PMID: 6775756.

10. Gupta D, Agarwal A, Nath SS, Goswami D, Saraswat V, Singh PK. Inflation with air via a facepiece for facilitating insertion of a nasogastric tube: a prospective, randomised, double-blind study. Anaesthesia. 2007; 62:127–130. PMID: 17223803.

11. Gombar S, Khanna AK, Gombar KK. Insertion of a nasogastric tube under direct vision: another atraumatic approach to an age-old issue. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2007; 51:962–963. PMID: 17635411.

12. Hung CW, Lee WH. A novel method to assist nasogastric tube insertion. Emerg Med J. 2008; 25:23–25. PMID: 18156534.

13. Moyers G, McDougle L. Use of the Cook airway exchange catheter in ‘bridging’ the potentially difficult extubation: a case report. AANA J. 2002; 70:275–278. PMID: 12242925.

Fig. 2

(A) Tube exchanger catheter was inserted through the nasogastric tube. (B) Levin tube was reconnected using connector straight.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download