This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

An 83-year-old woman was scheduled for a second transurethral resection of a bladder tumor. The preoperative electrocardiogram evaluation revealed atrial fibrillation with a slow ventricular response (ventricular rate: 59 /min). After intravenous injection of 1% lidocaine 40 mg and propofol 60 mg, the ventricular rate increased to 113 beats/min and then fell rapidly to 27 beats/min. Blood pressure was 70/40 mmHg. Later an atrial fibrillation rhythm, with a ventricular rate of 100-130 beats/min, was observed together with a sinus pause and sinus rhythm with a ventricular rate of 40-50 beats/min. An external pacemaker was applied and set at 60 mA, 40 counts. After the patient regained consciousness, she presented an alert mental state and had no chest symptoms. She was discharged 2 weeks later without complications after insertion of a permanent pacemaker.

Go to :

Keywords: Artificial cardaic pacing, Atrial fibrillation, Sick sinus syndrome

Tachycardia-bradycardia syndrome is a variant of sick sinus syndrome (caused by a functional defect of the sinus node, the primary pacemaker of the heart) in which slow and fast arrhythmias alternate [

1]. This can induce sinus arrest, sinus node exit block, sinus bradycardia and sinus tachycardia, and is also associated with paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (PSVT) and atrial fibrillation. When present in tachycardia- bradycardia syndrome, tachycardia is accompanied by long sinus pauses [

2].

Atrial fibrillation is one of the most common types of arrhythmias in elderly patients [

3]. Prior to an operation, patients with this arrhythmia require treatment and care because of the risk of ischemic heart disease, hypertensive heart disease, cardiac failure and embolism [

4]. Also, patients with slow ventricular rates not caused by rate-controlling medication are at risk of sick sinus syndrome, need careful history-taking to uncover syncopal or near-syncopal episodes, and may need a Holter monitor. We report a case of tachycardia- bradycardia syndrome that was discovered immediately after injecting intravenous lidocaine and propofol in a patient with atrial fibrillation and successfully treated with an external pacemaker.

Case Report

An 83-year-old woman (height: 168 cm, weight: 56 kg) was admitted to the outpatient center to receive a second transurethral resection of a bladder tumor (TURBT). The patient had underlying diabetes and hypertension and was taking a calcium channel blocker (Amlodipine) and an angiotensin II receptor blocker (Candelotan) for high blood pressure. She had undergone a hysterectomy 30 years previously and TURBT 2 months previously. She had suffered a stroke 2 years earlier but did not present sequelae. Her first TURBT had been uneventful.

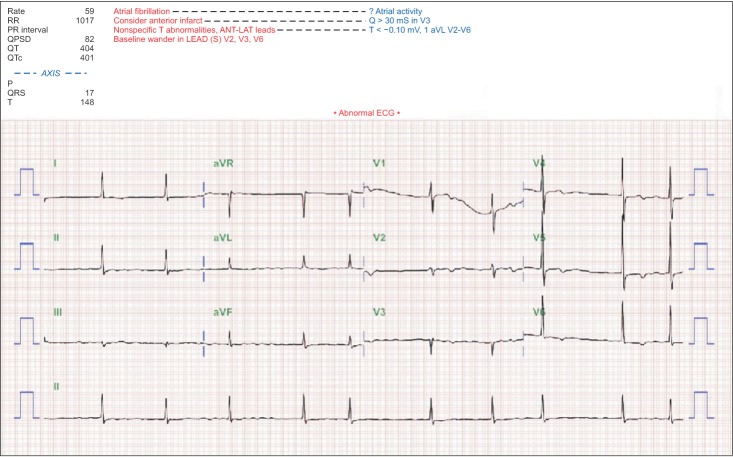

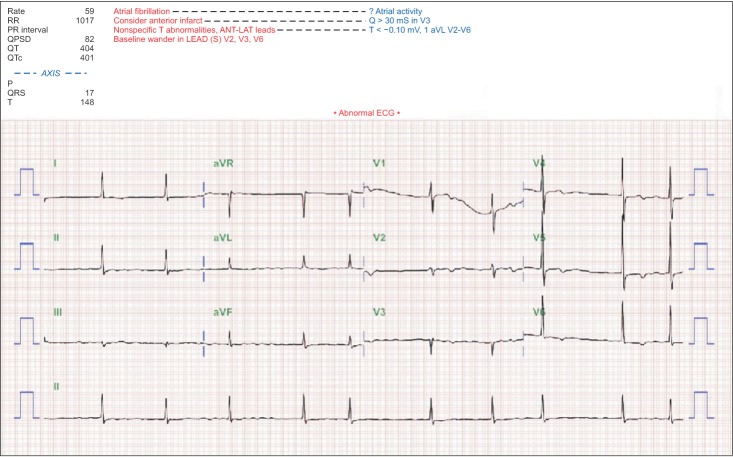

When the patient visited our hospital for her second TURBT the preoperative electrocardiogram (ECG) evaluation revealed atrial fibrillation with a slow ventricular response (ventricular rate: 59 beats/min) (

Fig. 1). There were no self-perceived symptoms. Ejection fraction 63%, eccentric left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), and left atrial enlargement (LAE) findings were obtained by transthoracic echocardiography. Cardiomegaly was observed in chest X-ray, and neck CT angiography showed total occlusion of the right internal carotid artery.

| Fig. 1Electrocardiogram shows artiral fibrillation with slow venstricular response (ventricular rate: 59 beats/min).

|

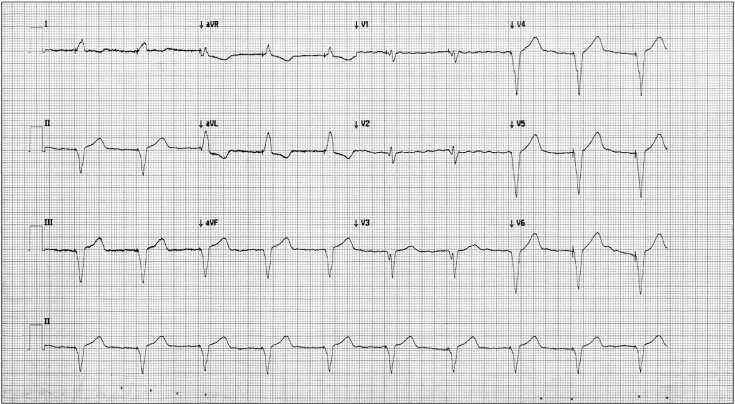

After the patient had been taken to the operating room, her vital signs were monitored using a non-invasive blood pressure measuring device, ECG and pulse oximeter. Before anesthesia, her blood pressure was 150/90 mmHg, pulse rate (ventricular rate) 90 beats/min and pulse oximetry of 100%. After use of a mask to supply 100% oxygen for 3 minutes before anesthesia, 1% lidocaine 40 mg and propofol 60 mg were injected intravenously. Thereafter, blood pressure declined to 130/72 mmHg whereas ventricular rate increased slightly to 113 beats/min and then fell rapidly to 27 beats/min with blood pressure of 70/40 mmHg. Ephedrine 5 mg was immediately injected intravenously. Ventricular rate responded with an increase to 120 beats/min but then decreased again after 8 seconds of sinus pause. Afterwards, atrial fibrillation rhythm, with a ventricular rate of 100-130 beats/min, was observed followed by a sinus pause, sinus rhythm, with a ventricular rate of 40-50 beats/min (

Figs. 2A, 2B and 2C). This cycle was repeated within a few minutes. An external pacemaker (LIFEPAK 20, Medtronic Co., Minneapolis, MN, USA) was applied and set at 60 mA, 40 counts. Pacing rhythms were observed during sinus pauses (

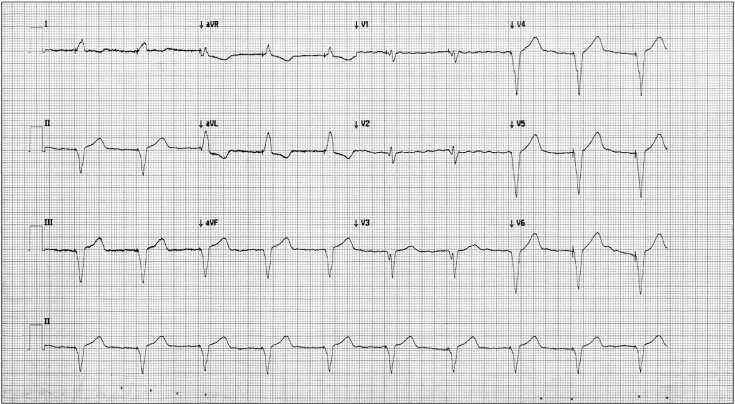

Fig. 2D). The breathing of the patient was adjusted by mask ventilation until she woke up. She then presented an alert mental status and had no chest symptoms. She was observed for 30 minutes in the operating room while the monitoring devices and use of the external pacemaker were maintained. The operation was put on hold by decision of the surgeon and the patient was transferred to the recovery room with external pacing. A 110-130 beats/min atrial fibrillation rhythm, 40-50 beats/min sinus rhythm and 40 beat/min pacing rhythm were also observed in the recovery room. There were no self-perceived symptoms. The patient was transferred for emergency coronary angiography. There were no abnormal findings for vascularity, and a temporary pacemaker was inserted into the right ventricle. The patient was transferred to the cardiology department and treated for 2 weeks after insertion of a permanent pacemaker. A 60 count pacing rhythm was observed in a follow-up ECG (

Fig. 3), and follow-up transthoracic echocardiography showed ejection fraction 65%, eccentric LVH, LAE, and the pacing rhythm was maintained without complications. The patient was discharged without any complications.

| Fig. 2Electrocardiogram monitored in the operation room. (A) Atrial fibrillation rhythm, with a ventricular rate of 100-130 beats/min, was observed before pacemaker insertion. (B) Sinus pause after atrial fibrillation rhythm was observed before pacemaker insertion. (C) Sinus rhythm, with a ventricular rate of 40-50 beats/min, was observed after atrial fibrillation rhythm and sinus pause before pacemaker insertion. (D) Pacing rhythms were observed during sinus pauses after pacemaker insertion.

|

| Fig. 3Electrocardiogram taken after insertion of a permanent pacemaker.

|

Go to :

Discussion

Atrial fibrillation is the most common type of arrhythmia in the elderly [

5] and it is 10-20 times more common than atrial flutter [

6]. It may cause no symptoms, but is often associated with palpitations, exercise intolerance, angina, congestive heart failure (shortness of breath, edema). Furthermore, as it is associated with the inability to fulfill preload caused by tachycardia, it can result in dyspnea on exertion, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, presyncope and syncope [

5]. Tachycardia- bradycardia syndrome can be generated by PSVT or atrial fibrillation. The symptoms are similar to those of atrial fibrillation: dizziness, fatigue, chest pain, angina, shortness of breath and fainting [

2]. In patients with atrial fibrillation, it is important to determine whether the fibrillation is associated with sick sinus syndrome or with chronic atrial fibrillation that have normal sinus function.

In our case, although atrial fibrillation was seen in the preoperative evaluation, the medical history of the patient was not sufficiently investigated. During pre-operative checking the patient was only asked about present chest symptoms or other symptoms related to the atrial fibrillation. In a detailed interview on the patient's medical history after she awoke in the operating room, it was discovered that the patient had experienced dizziness and felt her symptoms had been worsening over the last 2-3 weeks. Also she had experienced dyspnea (NYHA Class III) and palpitation, aggravated over the last 2-3 days, from one month before. She didn't say about this. If we had elicited more details of the patient's medical history in the pre-operative evaluation, we would have obtained more information on the type and progress of atrial fibrillation, and the effects of the disease on everyday life outside the hospital. As a consequence, sick sinus syndrome would have been suspected, and additional examinations such as Holter monitoring could have been carried out.

Atrial fibrillation is classified into 4 types according to its characteristics: initial diagnosis (first detected), self terminating episode lasting less than 7 days (paroxysmal), episode lasting more than 7 days (persistent) and sustained symptoms (permanent) [

5]. This patient was not classified in terms of type of atrial fibrillation in the pre-operative evaluation. Thus, access to the frequency of atrial fibrillation episodes and the level of the ordinary ventricular rate was inadequate. It is stipulated that 24 hour Holter monitoring is required for the patient treatment and care before operation. Our patient was classified as having persistent atrial fibrillation on her evaluation after pacemaker insertion.

When an atrial fibrillation patient shows signs of hemodynamic instability or symptoms of cardiac failure, electrical cardioversion is the most effective treatment for enhancing cardiac output and reducing the risk of thromboembolism [

5]. Atrial fibrillation can be converted to normal sinus rhythm by this treatment. Pharmacologic control can also be used to control ventricular rate [

5789]. Amiodarone, diltiazem, verapamil and digoxin can be used as medications, and AV nodal conduction can be slowed to adjust the ventricular response [

5789]. However, treating atrial fibrillation with cardioversion or medication can be hazardous if the sinus node is impaired [

2]. As these treatments can worsen bradyarrhythmia, a pacemaker must be inserted before pharmacologic control is attempted [

10]. If the bradycardia is not the result of drug therapy (ie, digitalis, beta-blockers), an abnormal sinus node physiology should be considered [

2]. Atrial fibrillation associated with tachycardia-bradycardia syndrome should be treated with a permanent pacemaker in combination with drugs [

210].

In our case, blood pressure and pulse oximetry were stable when the ventricular rate of the patient showed tachycardia. And the tachycardia was followed by severe bradycardia. Since we believed that our patient had tachycardia-bradycardia syndrome we started external pacing as quickly as possible without implementing cardioversion or medication. Our patient was started medication (verapamil for control rate, aspirin and warfarin for prevent thromoembolism) after insertion of pacemaker.

Many anesthetic agents (such as lidocaine, propofol, fentanyl, remifentanil, vecuronium and etc) have some effects on the cardiac conduction system [

1112131415]. They could have direct effect on sinus activity and incidence of bradycardia is higher if additional vagotomic agents. Choice of drug is very important in case of bradycardia and silent sick sinus syndrome. So, we should keep in mind these drugs can induce severe bradycardia. Lidocaine and propofol may have played a role in the development of bradycardia in our patient.

As shown in this case, serious complications can occur in atrial fibrillation patients. Thus, it is important to conduct a detailed, accurate interview and checkup on the patient's medical history and to evaluate the patient before operation. The existence of concealed sick sinus syndrome should be kept in mind in patients with atrial fibrillation. Furthermore, a defibrillator and external pacemaker must be available at all times in the operating room. Appropriate treatment must be initiated quickly to rectify the situation.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download