Abstract

Background

Transverse abdominis plane (TAP) block can be recommended as a multimodal method to reduce postoperative pain in laparoscopic abdominal surgery. However, it is unclear whether TAP block following local anesthetic infiltration is effective. We planned this study to evaluate the effectiveness of the latter technique in laparoscopic totally extraperitoneal hernia repair (TEP).

Methods

We randomly divided patients into two groups: the control group (n = 37) and TAP group (n = 37). Following the induction of general anesthesia, as a preemptive method, all of the patients were subjected to local anesthetic infiltration at the trocar sites, and the TAP group was subjected to ultrasound-guided bilateral TAP block with 30 ml of 0.375% ropivacaine in addition before TEP. Pain was assessed in the recovery room and post-surgery at 4, 8, and 24 h. Additionally, during the postoperative 24 h, the total injected dose of analgesics and incidence of nausea were recorded.

Results:

On arrival in the recovery room, the pain score of the TAP group (4.33 ± 1.83) was found to be significantly lower than that of the control group (5.73 ± 2.04). However, the pain score was not significantly different between the TAP group and control group at 4, 8, and 24 h post-surgery. The total amounts of analgesics used in the TAP group were significantly less than in the control group. No significant difference was found in the incidence of nausea between the two groups.

Go to :

Laparoscopic surgery is known to be less painful than open surgery. Nevertheless, many studies have reported the need to reduce pain following laparoscopic procedures. This may be because many patients still require painkillers to control postoperative pain, and surgical stimulation can lead to chronic pain.

Local anesthetic infiltration at incision sites is known to reduce the pain due to laparoscopic surgery, and its advantage is its easiness and safety [1,2]. Additionally, transverse abdominis plane (TAP) block is a recommended multimodal method of reducing postoperative pain in laparoscopic and open surgery [3,4].

However, according to recent reports, TAP block following local anesthetic infiltration at trocar sites offered no clinically important benefit in laparoscopic appendicectomy [5]. In patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy, TAP block was reported to be equivalent to local anesthetic infiltration for postoperative pain control [6].

Hence, the effectiveness of TAP block following local anesthetic infiltration is unclear. We planned the present study to evaluate the effectiveness of this technique in laparoscopic totally extraperitoneal hernia repair (TEP).

Go to :

The present study included 74 American Society of Anesthesiology physical status I, II in patients, aged 18 and older, who had undergone TEP under general anesthesia. Patients who underwent emergency surgery with complications and had a history of previous hernia repair or coagulopathy were excluded from the present study. Additionally, patients were excluded if they had little understanding of the pain score. The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our hospital, and written informed consent was obtained from all of the patients.

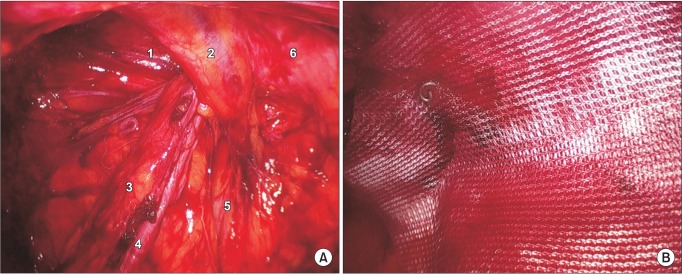

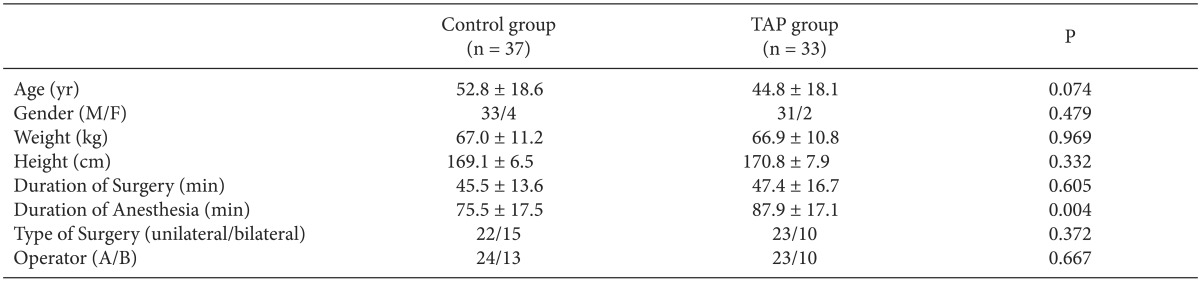

We randomly divided the patients into two groups: the control group and TAP group. An intramuscular injection of glycopyrrolate 0.2 mg was administered as premedication, and standard monitoring with electrocardiography, capnography, pulse oximetry, noninvasive blood pressure, and bispectral index (BIS) was applied. Anesthesia was induced with propofol 1-2 mg/kg, rocuronium 0.6 mg/kg and remifentanil 1 µg/kg. To maintain the proper depth of anesthesia, we used desflurane 6 vol% and maintained the mean arterial pressure at 60-100 mmHg and BIS at 40-60 by adjusting the infusion rate of remifentanil. After induction of anesthesia, ultrasound-guided bilateral TAP block with 30 ml of 0.375% ropivacaine was performed using the method reported by Hebbard et al. [7] in the TAP group only. We placed a probe immediately above the iliac crest vertical to the mid-axillary line, inserted a 22 G short bevel needle in the anterior axillary line, and injected into the TAP. All of the patients received preincisional infiltration in three or four trocar sites with 5 ml of 0.375% ropivacaine. TEP was performed using the classic method by two surgeons who were unaware of the patient groups and experienced in TEP (Fig. 1). The carbon dioxide infusion pressure was set at 12 mmHg, and a mesh was placed and fixed with a few tackers. Toward the end of the surgery, we stopped the infusion of remifentanil and recorded the amount used, and then administered propacetamol hydrochloride 1 g mixed with normal saline.

On arrival in the recovery room, if the patient complained of pain over the numeric rating scale (NRS) (0: no pain, 10: worst pain) 5 at rest or required analgesics, we administered fentanyl 50 µg intravenously. Every 10 min, we rechecked the pain score of the patient until discharge from the recovery room. If required by the patient or the NRS was greater than 5, fentanyl 50 µg was likewise administered after an interval of 10 min. In the patient ward, if the patient required a painkiller, ketorolac 30 mg was administered intravenously up to two times, and the pain score was recorded at 4, 8, and 24 h following surgery. Additionally, the total amount of analgesics used during the postoperative 24 h and the incidence of nausea were recorded. All data were measured and recorded by the investigator in a blinded manner.

The sample size was calculated from the pilot study. On arrival in the recovery room, the control group NRS was 5.62 ± 1.94; thus, an NRS less than 4 for the TAP group was considered clinically significant. Thirty-two subjects per group were needed for α = 0.05 and power = 0.9. However, thirty-seven subjects were actually included in each group considering the patient loss for observation. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version 14.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Student's t-test was used for continuous variables, and a chi-squared test and Fisher's exact test were used for categorical variables. A P value less than 0.05 was deemed to indicate statistical significance.

Go to :

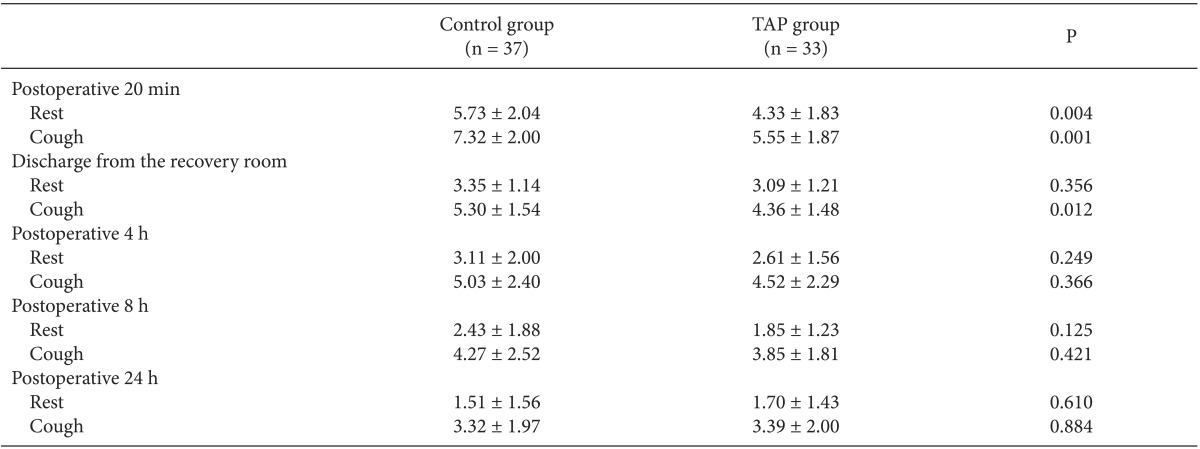

A total of 74 patients agreed to participate in the present study. However, the data were analyzed on 33 subjects in the TAP group and 37 subjects in the control group. Four subjects in the TAP group were excluded from the analyses. Of those, two subjects were discharged from the hospital on the day of surgery, and two subjects applied for intravenous patient-controlled analgesia before surgery.

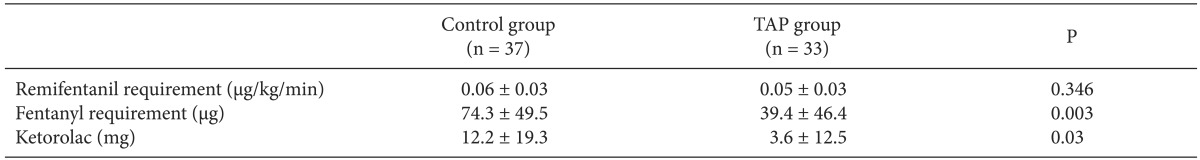

Patients' characteristics, with the exception of the duration of anesthesia showed no significant difference between the two groups (Table 1). The duration of anesthesia was longer by 12 min on average in the TAP group because of the TAP block. Table 2 shows the postoperative pain scores at each time point. In the recovery room, compared with the control group, the pain score in the TAP group was lower at rest and on coughing. However, when leaving the recovery room, no significant difference was noted at rest. In the patient ward up to 8 h post-surgery, although all NRS scores were lower in the TAP group, no significant difference compared with the control group was observed.

Table 3 shows the amounts of analgesics required. In the recovery room, the number of patients who were administered intravenous fentanyl was 30 (81.1%) in the control group and 17 (51.5%) in the TAP group. In the patient ward, the number of patients who required analgesics was 12 (32.4%) in the control group and 3 (9.1%) in the TAP group. No significant difference was noted in the incidence of nausea in the control group (5 [13.5%]) and TAP group (6 [18.2%]).

Go to :

Because local anesthetic infiltration at incision sites is easy, safe, and effective, it is regarded as a good method of reducing the pain due to laparoscopic surgery. Ahn et al. [2] reported that preincisional infiltration with bupivacaine reduced the postoperative pain scores and the amount of analgesics needed up to post-surgery 12 h in patients who underwent laparoscopic appendectomy. Pavlidis et al. [1] reported that preincisional periportal infiltration with ropivacaine is effective for pain control in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy or laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal hernia repair (TAPP) until 6 h postoperatively. Additionally, Cantore et al. [8] stated that pre-incision local infiltration is more effective than that post-incision.

TAP block blocks the sensory nerve supply to the anterior abdominal wall and is performed using a blind technique or ultrasonography. In recent years, ultrasound-guided TAP block has been performed most commonly because of its safety and accuracy. In laparoscopic surgery, the effectiveness of TAP block has been demonstrated in many studies. Of those studies, ultrasound-guided TAP block using a mid-axillary approach has led to good postoperative pain control in laparoscopic cholecystectomy, laparoscopic bariatric surgery, laparoscopic colorectal surgery, and ambulatory gynecological laparoscopic surgery [3,4,9,10,11].

In direct comparison studies of TAP block and local anesthetic infiltration, Tolchard et al. [12] stated that subcostal TAP block is superior to conventional port-site infiltration using the same amount of bupivacaine for postoperative analgesia of 43 patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. However, Ortiz et al. [6] reported that bilateral ultrasound-guided TAP block using a mid-axillary approach is equivalent to local infiltration of trocar sites for overall postoperative pain in 80 patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. In the above two studies, TAP block was not performed using the same method. Although the subcostal approach could be superior to the mid-axillary approach in laparoscopic cholecystectomy, this has not yet been demonstrated in a sufficient number of studies. Thus, it is unclear whether TAP block is more effective than local anesthetic infiltration in laparoscopic surgery.

Few studies have investigated the effectiveness of TAP block following local anesthetic infiltration. Sandeman et al. [5] reported that TAP block following local infiltration of trocar sites in 72 children undergoing laparoscopic appendicectomy conferred no benefit, and no difference was noted in the total dose of patient-controlled analgesia morphine used and pain scores between the groups with or without TAP block.

We believed that ultrasound-guided bilateral TAP block would be more effective in TEP than in laparoscopic appendicectomy because TEP is performed in the preperitoneal space of the lower abdomen. Tran et al. [13] stated that ultrasound-guided TAP block using a mid-axillary approach could be used restrictively for lower abdominal surgery because only T10-L1 was stained when TAP block was performed using 20 ml dye in a cadaver study. Thus, we planned to demonstrate the effectiveness of TAP block following local anesthetic infiltration in TEP. In our study, the pain score in the recovery room immediately after TEP was significantly lower in the TAP group than in the control group. However, we could not demonstrate a continuous analgesic effect of TAP block using pain scores, although the amount of analgesics used was significantly lower than that in the TAP group. The reason is considered to be due to the fact that the local infiltration may result in a considerable reduction of pain in both groups. Another reason could be that pain reduction on the day of surgery is faster than other laparoscopic surgery [3].

Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair is usually performed using one of two methods-TAPP and TEP. Similar to other abdominal surgery techniques, the laparoscopic procedure for inguinal hernia repair has the advantage of rapid recovery, fewer complications, and rapid return to work [14,15]. Of the two methods, TEP is performed not in the intraperitoneal cavity but in the preperitoneal space. Hence, TEP has some advantages over TAPP with respect to the rate of port-site hernia [16], and the postoperative pain may be more limited to the lower abdominal area than with TAPP. In our study, the areas of pain that patients primarily complained of were the trocar site of the umbilicus and the hernia site at which the surgical procedure was carried out; no patient complained of shoulder pain due to carbon dioxide insufflations, unlike in other laparoscopic surgical techniques.

The factors associated with postoperative pain in TEP include tissue dissection, gas insufflations to the preperitoneal space, and mesh fixation [17]. Several trials have aimed to reduce post-surgical pain following TEP. Hon et al. [18] reported that preemptive infiltration to all of the port sites and instillation to the preperitoneal space with 20 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine significantly reduced postoperative pain for up to 24 h without increasing complications such as seroma; hence, it can be recommended as routine practice. Kumar et al. [19] reported that, although preperitoneal instillation with 30 ml of 0.25% bupivacaine toward the end of surgery showed no difference compared with the control group in terms of the time of return to work, the pain score was reduced for up to 48 h.

We did not perform preperitoneal instillation with local anesthetics in the present study because, if performed following TAP block, serious neurotoxicity could result. Griffiths et al. [20] stated that TAP block using 3 mg/kg ropivacaine could lead to neurologic complications because of the high blood concentration of ropivacaine. Hence, we used a total of 131 mg of ropivacaine in the TAP group.

Less remifentanil was infused in the TAP group than in the control group, albeit not significantly so. We believe that the short operation duration might be the reason for the lack of a difference in the dose of remifentanil used in the two groups.

The limitation of the present study is its possible bias due to the technique being performed by two surgeons, although TEP was performed by the same team.

In conclusion, we suggest that TAP block following local anesthetic infiltration could be a multimodal method of reducing the amount of analgesics and pain immediately after TEP. However, to recommend its routine use in patients undergoing TEP, we believe that additional studies that include assessment of the quality of recovery and patient satisfaction should be carried out to demonstrate its effectiveness.

Go to :

References

1. Pavlidis TE, Atmatzidis KS, Papaziogas BT, Makris JG, Lazaridis CN, Papaziogas TB. The effect of preincisional periportal infiltration with ropivacaine in pain relief after laparoscopic procedures: a prospective, randomized controlled trial. JSLS. 2003; 7:305–310. PMID: 14626395.

2. Ahn SR, Kang DB, Lee C, Park WC, Lee JK. Postoperative pain relief using wound infiltration with 0.5% bupivacaine in single-incision laparoscopic surgery for an appendectomy. Ann Coloproctol. 2013; 29:238–242. PMID: 24466538.

3. Ra YS, Kim CH, Lee GY, Han JI. The analgesic effect of the ultrasound-guided transverse abdominis plane block after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2010; 58:362–368. PMID: 20508793.

4. El-Dawlatly AA, Turkistani A, Kettner SC, Machata AM, Delvi MB, Thallaj A, et al. Ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane block: description of a new technique and comparison with conventional systemic analgesia during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Anaesth. 2009; 102:763–767. PMID: 19376789.

5. Sandeman DJ, Bennett M, Dilley AV, Perczuk A, Lim S, Kelly KJ. Ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane blocks for laparoscopic appendicectomy in children: a prospective randomized trial. Br J Anaesth. 2011; 106:882–886. PMID: 21504934.

6. Ortiz J, Suliburk JW, Wu K, Bailard NS, Mason C, Minard CG, et al. Bilateral transversus abdominis plane block does not decrease postoperative pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy when compared with local anesthetic infiltration of trocar insertion sites. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2012; 37:188–192. PMID: 22330261.

7. Hebbard P, Fujiwara Y, Shibata Y, Royse C. Ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2007; 35:616–617. PMID: 18020088.

8. Cantore F, Boni L, Di Giuseppe M, Giavarini L, Rovera F, Dionigi G. Pre-incision local infiltration with levobupivacaine reduces pain and analgesic consumption after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a new device for day-case procedure. Int J Surg. 2008; 6(Suppl 1):S89–S92. PMID: 19264565.

9. Sinha A, Jayaraman L, Punhani D. Efficacy of ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane block after laparoscopic bariatric surgery: a double blind, randomized, controlled study. Obes Surg. 2013; 23:548–553. PMID: 23361468.

10. Walter CJ, Maxwell-Armstrong C, Pinkney TD, Conaghan PJ, Bedforth N, Gornall CB, et al. A randomised controlled trial of the efficacy of ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block in laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Surg Endosc. 2013; 27:2366–2372. PMID: 23389068.

11. De Oliveira GS Jr, Fitzgerald PC, Marcus RJ, Ahmad S, McCarthy RJ. A dose-ranging study of the effect of transversus abdominis block on postoperative quality of recovery and analgesia after outpatient laparoscopy. Anesth Analg. 2011; 113:1218–1225. PMID: 21926373.

12. Tolchard S, Davies R, Martindale S. Efficacy of the subcostal transversus abdominis plane block in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Comparison with conventional port-site infiltration. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2012; 28:339–343. PMID: 22869941.

13. Tran TM, Ivanusic JJ, Hebbard P, Barrington MJ. Determination of spread of injectate after ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane block: a cadaveric study. Br J Anaesth. 2009; 102:123–127. PMID: 19059922.

14. Memon MA, Cooper NJ, Memon B, Memon MI, Abrams KR. Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials comparing open and laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg. 2003; 90:1479–1492. PMID: 14648725.

15. Bittner R, Arregui ME, Bisgaard T, Dudai M, Ferzli GS, Fitzgibbons RJ, et al. Guidelines for laparoscopic (TAPP) and endoscopic (TEP) treatment of inguinal hernia [International Endohernia Society (IEHS)]. Surg Endosc. 2011; 25:2773–2843. PMID: 21751060.

16. Felix EL, Michas CA, Gonzalez MH Jr. Laparoscopic hernioplasty. TAPP vs TEP. Surg Endosc. 1995; 9:984–989. PMID: 7482218.

17. Tam KW, Liang HH, Chai CY. Outcomes of staple fixation of mesh versus nonfixation in laparoscopic total extraperitoneal inguinal repair: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J Surg. 2010; 34:3065–3074. PMID: 20714896.

18. Hon SF, Poon CM, Leong HT, Tang YC. Pre-emptive infiltration of Bupivacaine in laparoscopic total extraperitoneal hernioplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Hernia. 2009; 13:53–56. PMID: 18704618.

19. Kumar S, Joshi M, Chaudhary S. 'Dissectalgia' following TEP, a new entity: its recognition and treatment. Results of a prospective randomized controlled trial. Hernia. 2009; 13:591–596. PMID: 19644647.

20. Griffiths JD, Barron FA, Grant S, Bjorksten AR, Hebbard P, Royse CF. Plasma ropivacaine concentrations after ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane block. Br J Anaesth. 2010; 105:853–856. PMID: 20861094.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download