Introduction

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is a common adverse event in patients undergoing surgeries for breast and thyroid cancers, which are the most frequent malignant neoplasms in women. It has been reported that the incidences of PONV are between 60 and 80% for mastectomy and thyroidectomy, respectively [

1,

2]. The first step for the prevention of PONV is to reduce risk factors, i.e., by the use of propofol-based anesthesia and decreased use of intraoperative N

2O and postoperative opioids. Secondly, prophylactic antiemetics are available [

3]. Some studies have indicated that total intravenous anesthesia using propofol and remifentanil might alleviate PONV during the early postoperative period (< 24 h) compared to volatile anesthesia [

4].

Despite the positive effects of propofol for reducing PONV, it has the major problem of causing pain and discomfort on injection. Recall of injection pain during the induction of anesthesia may have an impact on overall patient satisfaction with anesthetic care. Although the mechanism of the injection pain caused by propofol remains unclear, it has been postulated that it may be associated with a direct irritant effect or an indirect effect due to the release of pro-inflammatory mediators [

5]. The mediators that are related to propofol-related injection pain may also be involved as a mechanism of pain associated with rocuronium injection [

6].

Several studies have demonstrated that some 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT

3) receptor antagonists such as ondansetron and granisetron can reduce the incidence of propofol-related injection pain [

5,

7]. One study has reported that pretreatment with ondansetron was also effective for alleviating the pain on injection of rocuronium [

6]. Palonosetron, a new, long-acting, 5-HT

3 receptor antagonist, has been commonly used in our hospital for PONV following anesthesia or in the postanesthetic care unit (PACU). To our knowledge, there is no published data available regarding the effect of palonosetron on reducing propofol- and rocuronium-related injection pain. We designed this double blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study to determine the efficacy of the pretreatment with palonosetron for alleviating the injection pain of both propofol and rocuronium. We also evaluated the effect of the pretreatment with palonosetron on PONV, shivering, postoperative pain, and overall satisfaction of patients undergoing surgery for breast and thyroid cancers.

Go to :

Materials and Methods

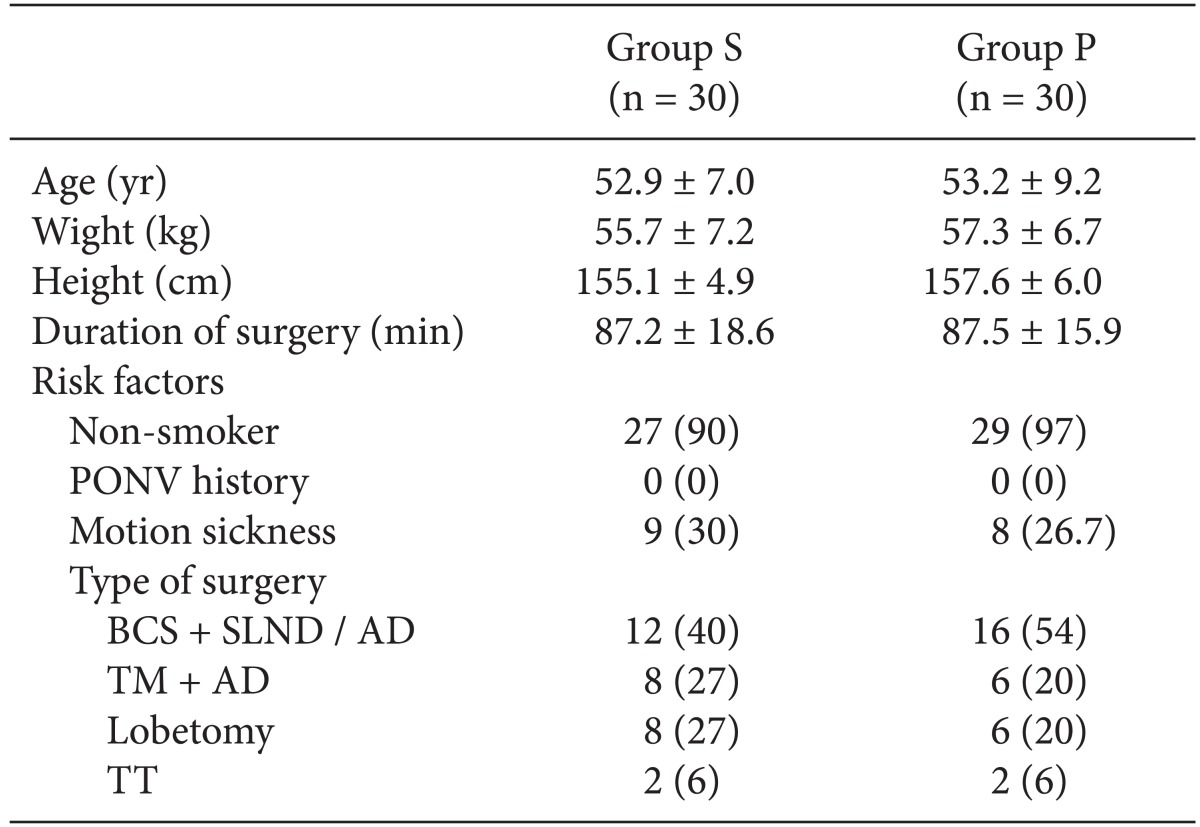

After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval of our hospital, written informed consent was obtained from all participating patients. Sixty women, aged 20 to 65 years, who were scheduled to undergo general anesthesia for breast and thyroid cancer surgery and were classified as American Society of Anesthesiology physical status of I-II, were enrolled in this study. Patients with a history of severe cardiovascular or respiratory distress, morbid obesity, drug or alcohol abuse, history of adverse medication reactions, and chronic pain, and patients who had received any antiemetics, sedatives, or analgesics within 24 h before surgery were excluded from the study. An 18-gauge intravenous catheter was inserted in a vein on the dorsum of the hand apart from surgical field and an infusion of Hartmann's solution was started in the ward. We excluded the patients if we could not get intravenous access at the desired vein. Patients were evaluated for the risk factors of PONV including a history of PONV, motion sickness, and nonsmoking status.

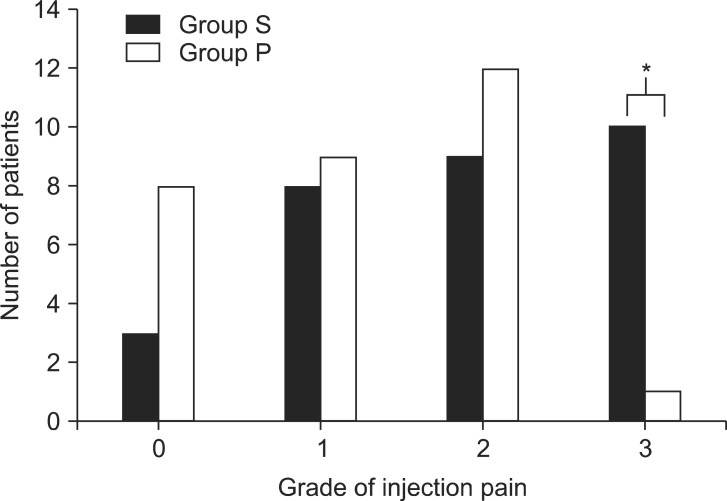

All patients were premedicated with glycopyrrolate 0.2 mg intramuscularly 30 min before the induction of anesthesia. When patients arrived at the operating room, electrocardiogram, blood pressure, bispectral index (BIS), and pulse oximetry monitoring were initiated. Patients were randomly allocated to one of two groups by the investigator using a sealed envelope system. All syringes of the pretreatment drugs were prepared by an anesthetic nurse under the supervision of the investigator. The patients received the pretreatment injection of normal saline 4 ml (group S) or palonosetron 75 µg (1.5 ml) diluted with 2.5 ml normal saline (group P) over a period of 30 s after venous occlusion at the forearm using an elastic tourniquet. Two minutes after the administration of the pretreatment drug, the tourniquet was removed and anesthetic induction with 6 µg effect-site concentration (Ce) of propofol was initiated. The effect-site target controlled infusion (TCI) of propofol and remifentanil was performed by TCI pump (Orchestra Base Prima, Fresenium Vial, France). An anesthesiologist who was blinded to the nature of the pretreatment drugs asked the patients to evaluate the pain score at the injection site. Pain was graded from 0 to 3 in accordance with the design of McCrirrick A and Hunter [

8], where 0 = no pain (negative response to questioning), 1 = mild pain (pain reported only in response to questioning without any behavioral signs), 2 = moderate pain (pain reported in response to questioning and accompanied by a behavioral signs or pain reported spontaneously without questioning), and 3 = severe pain (vocal response accompanied by facial grimacing, arm withdrawal, or tears).

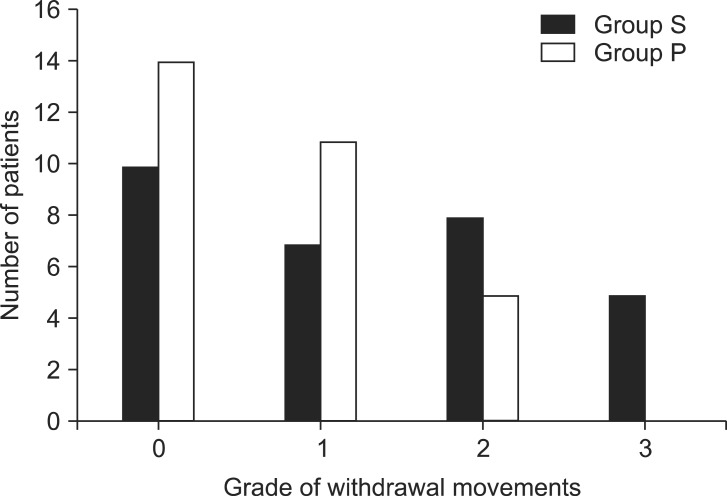

If the patients experienced the severe pain, the proximal portion of the injection site was gently touched and rubbed until I.V. anesthesia took effect. After loss of consciousness and upon BIS 40-60, rocuronium bromide (0.6 mg/kg) was administered to facilitate orotracheal intubation. The independent anesthesiologist observed the patients and assessed the severity of withdrawal movements in response to rocuronium. The withdrawal score was graded as 0 = no response, 1 = movement at the wrist only, 2 = movement involving the arm only to elbow or shoulder, and 3 = generalized response of movement in more than one extremity and reactions indicating discomfort or pain [

9].

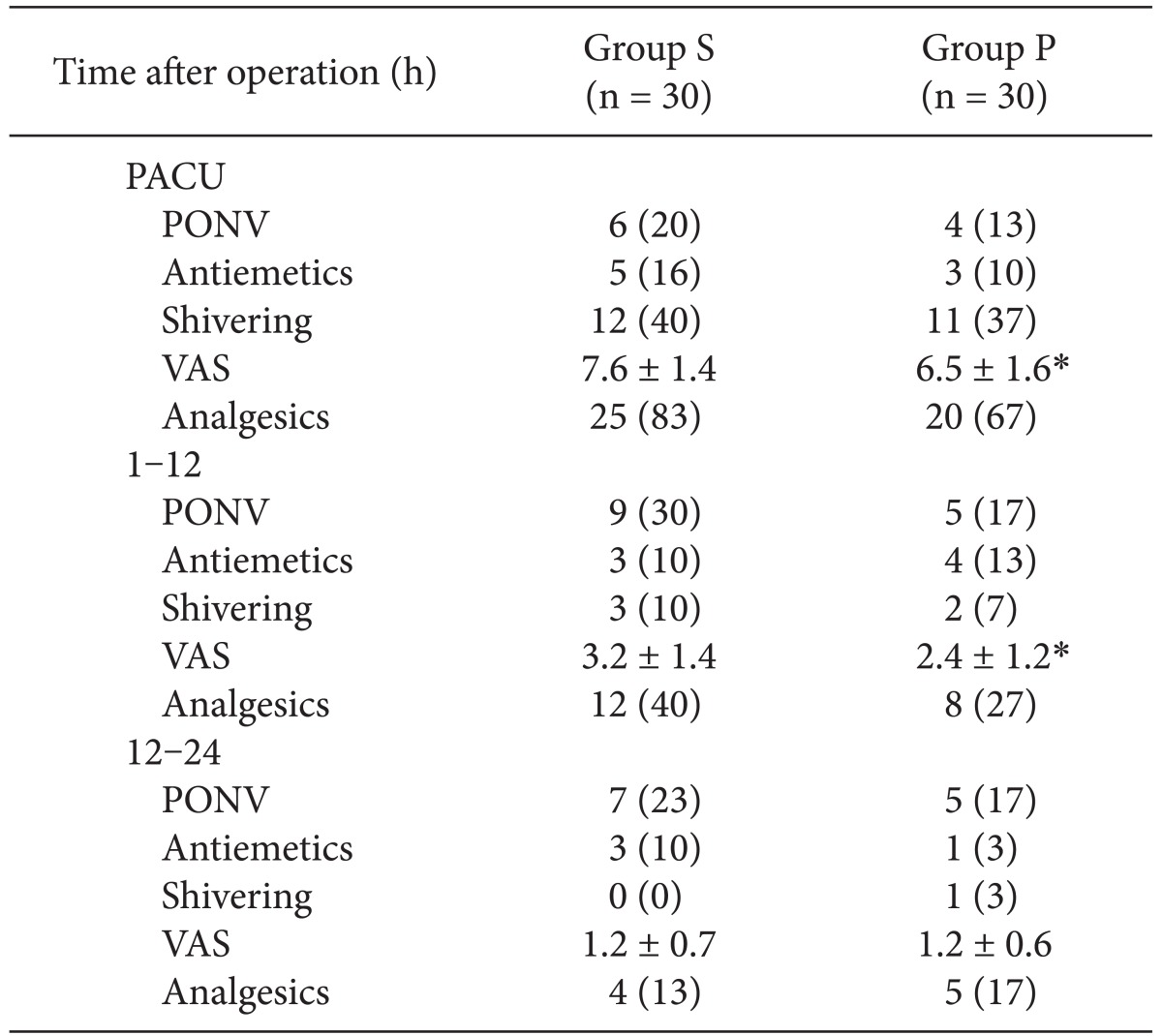

Anesthesia was maintained with propofol (Ce 2 to 5 µg/ml), remifentanil (Ce 1 to 2.5 ng/ml), nitrous oxide 50% in oxygen, and mechanical controlled ventilation, and rocuronium was given if required. Muscle relaxation was antagonized by glycopyrrolate 0.4 mg and pyridostigmine 15 mg. A blinded nurse assessed the patients in the PACU for serious complications such as extrapyramidal reactions or hallucinations and illusions, if any. Note was also made of the incidence of PONV and shivering, and pain was assessed using a visual analogue scale (VAS, 0 to 10, no pain to the most severe pain). Rescue antiemetics and analgesics for treatment of PONV and pain were ordered by the independent anesthesiologists as needed. Metoclopramide 10 mg or ondansetron 4 mg were intravenously administered as rescue antiemetics during the first postoperative 24 h. If a patient required analgesics, ketorolac 30 mg was injected intravenously.

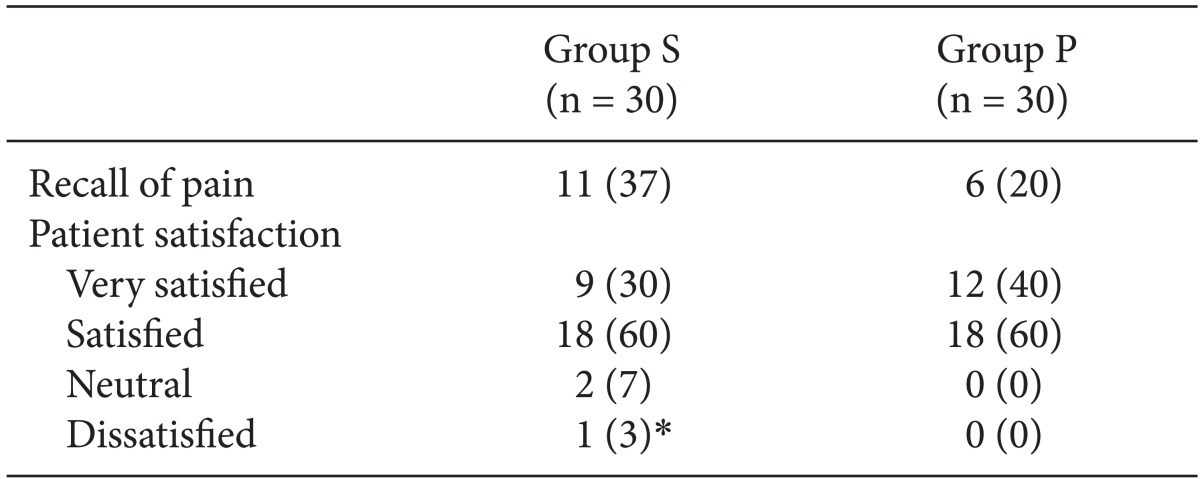

At 12 and 24 h after surgery, a blinded researcher assessed allergic reactions, edema, pain at the injection site, PONV, shivering, VAS, and the use of rescue antiemetics and analgesics. All patients were asked 24 h postoperatively about recall of injection pain during induction of anesthesia. They were also asked to rate their satisfaction with the overall anesthetic care experience (very satisfied, satisfied, neutral, or dissatisfied).

All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS (Windows version 17.0, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Power analyses indicated that 27 patients would be necessary in each group to demonstrate a reduction of pain score of 1 at an α-value of 0.05 and power of 80%. We increased the sample size to 30 patients in each group based on the possibility of a 10% dropout rate. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables are expressed as frequency distribution and percentage (%). The results were statistically analyzed using Chi-square test, Fisher's exact tests, and unpaired Student's t-test when appropriate. Results were considered statistically significant when a P value of < 0.05 was obtained.

Go to :

Discussion

This study demonstrated that, compared to saline, pretreatment with palonosetron with simultaneous venous occlusion was efficacious for reducing the severity of the pain occurring during injection of propofol, although it did not reduce the overall incidence of injection pain associated with propofol and rocuronium. Palonosetron reduced the level of postoperative pain during the first 12 h after surgery. PONV during the first postoperative day are rare in patients undergoing total intravenous anesthesia using propofol-remifentanil for breast and thyroid cancer surgery, so we could not distinguish the efficacy of palonosetron for the prevention of early PONV.

Pain on injection of anesthetics may be an important cause of patient dissatisfaction during the perioperative period. One patient in our saline group recalled induction of anesthesia as the most painful part of the perioperative period and reported dissatisfaction with the overall anesthetic care. The pain on injection of propofol is ranked seventh among the 33 most problematic low-morbidity perioperative outcomes [

10]. An incidence of pain of about 60% on injection of propofol without any preventive measures has been reported [

11].

The mechanism of propofol-related injection pain is not established, but it has been suggested that it is due to endothelial irritation resulting from the chemical phenol properties of propofol along with activation of the kallikrein-kinin system that is known to play a role in inflammation [

5]. Propofol injection, therefore, may be associated with the release of histamine, bradykinin, and other inflammation-mediating substances, and Borgeat and Kwiatkowkski [

12] have demonstrated that the mechanism of rocuronium-associated pain may be related to a direct irritant effect on the kinin cascade. The nature of the pain on injection of rocuronium is similar to the nature of the pain induced by the injection of propofol. Lidocaine is the most common agent given before injection to prevent propofol- or rocuronium-related injection pain, although the protection is not complete [

6].

Ye et al. [

13] have reported that ondansetron has a 15-fold-higher potency as a local anesthetics, than lidocaine injected under the skin via a dual mechanism of sodium channel blockade and 5HT

3 receptor antagonism. Intrathecal ondansetron has been shown to reduce the nociceptive response of dorsal horn neurons in the rat spinal cord [

14]. Ondansetron has also been shown to combine with µ opioid receptors in humans and show agonist activity [

15], and 5-HT

3 receptors have been shown to be located in the nociceptive fibers of the dorsal horn and in the peripheral nervous system and to modulate nociceptive pathways [

16]. Antagonism of 5-HT

3 receptors in the spinal cord is associated with an antinociceptive effect for acute pain evoked by formalin stimulus [

17]. As a result of its multifunction as a sodium channel blocker, µ opioid agonist, and 5-HT

3 receptor antagonist, ondansetron should be useful to reduce the pain produced by propofol and rocuronium injection [

6]. Other 5HT

3 receptor antagonists, such as granisetron and ramosetron, have also been shown to alleviate the injection pain of propofol compared to the placebos [

7,

18].

The 5-HT

3 receptor antagonist palonosetron has a greater binding affinity and longer half-life than other 5-HT

3 receptor antagonist [

19]. The unique pharmacokinetics of palonosetron have been associated with clinical outcomes including better prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting compared with other 5-HT

3 drugs [

20]. We presumed that palonosetron, as a more refined 5-HT

3 receptor antagonist, could relieve the injection pain associated with propofol and rocuronium by a similar mechanism. Our results demonstrated a high incidence of pain in all patients: 90% in the saline group and 73% in the palonosetron group, but the rate of severe pain was significantly lower in palonosetron group (3%) compared to the saline group (33%). Palonosetron was less successful in reducing the overall incidence of pain in comparison studies with ondansetron vs. placebo (25% vs. 50%) and granisetron vs. placebo (15% vs. 60 %) pretreatment [

5,

7]. This may be explained by the different molecular structure of palonosetron, which also interacts with 5-HT

3 receptors at different sites than the older HT

3 receptor antagonists [

21]. Rojas et al. [

21] have reported that palonosetron has allosteric interactions and positive cooperativity with 5-HT

3 receptors and that these characteristics were not present in the other 5-HT

3 receptor antagonists. These may produce the pharmacological differences noted in clinical studies comparing palonosetron to other 5-HT

3 receptor antagonists.

We chose a 2-min interval between the injection of palonosetron and the infusion of propofol with the presumption that this period might be sufficiently longer vs. previous studies with granisetron and ondansetron [

5,

7]. The reduced effectiveness of palonosetron for injection pain in comparison to the other agents may also be explained by a delayed onset of action, which is a pharmacokinetic character of the long-acting agent. There is no prior evidence or study regarding the onset of action of palonosetron, although Lummis and Thompson [

22] have reported that association of palonosetron at both 5-HT

3A and 5-HT

3B receptors was compared in 30 min with t

1/2 values of 4.1 and 2.0 min, respectively.

In the present study, pretreatment with palonosetron did not prevent withdrawal movements due to rocuronium injection. The exact mechanism of the injection pain of rocuronium is not still clearly understood. The pain may be induced by low pH or by the release of local mediators such as kinin, histamine, and other pro-inflammatory substances [

23]. Our study indicated that palonosetron was not effective in preventing the injection pain leading to withdrawal movement of arms, which may be explained by the same reasons presumed in the results of the incidence propofol-associated injection pain.

With regard to postoperative pain, our results demonstrated that the palonosetron group had reduced pain during assessment in the PACU and during the first 12 h after surgery. The 5-HT

3 receptor is known to have pronociceptive abilities and to relate to the spinobulbospinal loop that is stimulated by superficial neurokinin 1 receptor-expressing neurons [

24], and McClean et al. [

25] have reported that ondansetron was effective in alleviating chronic neuropathic pain. To date, there are no published data available regarding the antinociceptive effect of palonosetron other than one study showing that palonosetron had no effect on modulation of mechanical allodynia in a postoperative rat pain model [

26].

We omitted premedication with sedatives or anxiolytic agents such as midazolam and tried to assess the recall of the patients of pain and discomfort during propofol or rocuronium injection. Although there was an unacceptably high incidence of injection pain in the patients in the present study, dissatisfaction with the overall anesthetic care, including recall of pain was rare among the patients in either group. We used light touch and rubbing at the injection site after grading pain if the patients experienced severe pain during the pain assessment. Kim et al. [

27] reported that rubbing and light touch significantly decreased moderate and severe pain, although they did not have a reduced incidence of pain.

We found that 40% of the patients in the saline group and 36.7% in the palonosetron group had postoperative shivering and that the pretreatment with palonosetron had no anti-shivering effect. These findings were similar to those of a previous study conducted in patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery under total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA) [

28]. In that study, Jo et al. [

28] speculated that the ineffectiveness of palonosetron against shivering was related to smaller doses or the failure of the 5-HT

3 antagonist against acute remifentanil-induced tolerance.

In general, 5-HT

3 receptor antagonists are well tolerated with few side effects including headache, dizziness, and constipation. In our study, there were no adverse effects such as extrapyramidal reactions or hallucination and illusion, which have occurred rarely after the use of ondansetron [

29].

There was a low incidence of PONV during the first 24 h after surgery in the present study, different from results of previous studies regarding PONV associated with breast and thyroid surgery [

1,

2]. The incidence of PONV is known to be influenced by patient characteristics, type of surgical procedure, anesthesia technique, and postoperative analgesics [

3]. Generally, female gender, a history of motion sickness, previous PONV, and nonsmoking are risk factors associated with PONV [

3], and we had no differences in these risk factors between the two groups in the present study. Kim et al. [

4] reported that the incidence of PONV during the first 24 h after endoscopic thyroidectomy was 14.6% in a TIVA group compared to 51% in a balanced anesthesia group. Their result revealed a lower incidence of PONV in endoscopic thyroidectomy compared to open thyroidectomy through the antiemetic effect of TIVA. We also observed the morbidity of PONV only during the first 24 h after surgery and could assert that TIVA using propofol-remifentanil reduced the incidence of early PONV for this study. We used only NASAIDs as rescue analgesics and avoided the use of the opioids, that may increase the incidence of PONV.

We failed to show an efficacy of palonosetron for PONV, although a previous study demonstrated excellent prevention PONV by palonosetron during a postoperative period of 72 h [

30]. Our results may need to be interpreted with consideration of other clinical factors, particularly the single-center, smaller study, in which the low overall incidence of PONV may also be related to the unusual proficiency of surgeons masking the nature of emetogenic procedures. Also, although the sample size of this study was acceptable for the analysis of injection pain induced by anesthetics, it may have been insufficient for the study of PONV. We did not observe PONV after the first 24 h after surgery or the long-lasting antiemetic effect of palonosetron, which may be efficient in late PONV.

In conclusion, it was shown in this study, that pretreatment with palonosetron was effective for alleviating the severity of pain during injection of propofol as well as early postoperative pain. There has been a low incidence of PONV in patients who received TIVA using propofol and remifentanil for breast and thyroid cancer surgery. Therefore, the efficacy of palonosetron for the prevention of PONV was not clear during the first postoperative 24 h.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download