Abstract

We present a case of a patient exhibiting isolated elevation of the central venous pressure with minimal hemodynamic deterioration in an immediate postoperative period after Bentall operation requiring re-exploration. Isolated elevation of the central venous pressure usually alerts physicians of a volume overload or right ventricular dysfunction. However, even in the absence of significant hemodynamic deterioration, the development of loculated hematoma that compresses the superior vena cava should be ruled out, as it can be life-threatening through the formation of cerebral and laryngeal edema, similar to superior vena cava syndrome. This case emphasizes the importance of a prompt differential diagnosis of the isolated central venous pressure elevation after cardiac surgery with transesophageal echocardiography for the administration of appropriate treatment.

Following cardiac surgery, an isolated elevation of the central venous pressure (CVP) is frequently observed as the result of circulatory volume overload and/or right ventricular (RV) dysfunction, which is usually amenable to medical therapy. In contrast, an elevation of the CVP with pressure equalization close to pulmonary artery diastolic pressure, along with hemodynamic deterioration, indicates postoperative hemorrhage and cardiac tamponade, which requires immediate re-exploration. However, loculated pericardial hematoma may not exhibit typical signs of cardiac tamponade, which can interfere with giving a proper diagnosis. Loculated hematoma compressing the superior vena cava (SVC) can cause isolated elevations of the CVP without significant hemodynamic deterioration. Yet, this situation requires prompt surgical decompression, as it can be life-threatening due to the formation of cerebral and laryngeal edema, similar to SVC syndrome. We, herein, report a case of a patient whose CVP was markedly increased immediately after a Bentall operation due to the formation of loculated hematoma compressing the SVC.

A 70-year-old male patient underwent a Bentall operation due to annulo-aortic ectasia, which was combined with severe aortic valvular insufficiency. The patient's height and weight were 165 cm and 50.9 kg, respectively and he had no co-morbid diseases except for hypertension, which was treated with a calcium channel blocker and an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor. The patient had a normal sinus rhythm, and the preoperative transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) revealed a left ventricular ejection fraction of 58% with no other intracardiac pathologies. Coronary angiography also revealed normal coronary arteries. After anesthetic induction, the patient's hemodynamic variables were as follows; systemic blood pressure 113/38 mmHg, heart rate 83 beats/min, central venous pressure 9 mmHg, and pulmonary arterial pressure 33/15 mmHg. A Bentall procedure was uneventfully performed and the patient was weaned off from cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) without difficulty. The total aorta cross clamp time was 95 minutes and the total CPB time was 115 minutes. Before leaving the operating room, there was no evidence of fluid collection in the pericardial and pleural space in the transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), with the estimated left ventricular ejection fraction being 50%. Receiving norepinephrine 0.08 µg/kg/min, milrinone 0.25 µg/kg/min, and vasopressin 0.8 IU/hr, the hemodynamic parameters were as follows: heart rate of 80 beats/min, blood pressure of 87/48 mmHg, CVP of 10 mmHg, pulmonary arterial pressure of 24/15 mmHg, cardiac index of 3.4 L/min/m2, mixed venous oxygen saturation of 90%, right ventricular ejection fraction of 39%, and right ventricular end diastolic volume index of 141 mm/m2. The patient was transported to the intensive care unit (ICU) without any further events. In the ICU, as in the operating room, the patient's lungs were ventilated with a tidal volume of 500 ml at a rate of 12 breaths/min, with a fraction of inspired oxygen of 40% medical air, along with 5 cmH2O of positive end-expiratory pressure. The corresponding peak airway pressure and plateau airway pressure were 19 cmH2O and 17 cmH2O, respectively. The arterial blood gas analysis revealed pH 7.419, PaO2 123.8 mmHg, and PaCO2 34.7 mmHg. Over a period of 30 minutes in the ICU, the CVP increased from 10 to 23 mmHg, and the pulmonary artery diastolic pressure increased from 14 to 17 mmHg. The blood pressure was 90/49 mmHg, and the cardiac index was maintained at 2.7 L/m/m2 without increasing doses of norepinephrine, milrinone, and vasopressin. The electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed nonspecific ST wave changes without any changes in the height of the QRS waves, and the chest X-ray showed partial atelectasis of the right lung and moderate cardiomegaly. The patient's respiratory mechanics and follow-up arterial blood gas analysis showed no significant changes. His hemoglobin was 8.7 g/dl which is near the former value measured in the operating room of 9.0 g/dl. The platelet count was 82 × 109/L and the International Normalized Ratio of the prothrombin time was slightly elevated at 1.54. During the first 15 minutes after the surgery, 100 ml of blood were drained from his mediastinal and chest drains. Because, there was no further chest tube drainage, 100 ml of 6% hydroxyethyl starch 130/0.4 solution was infused without any transfusions.

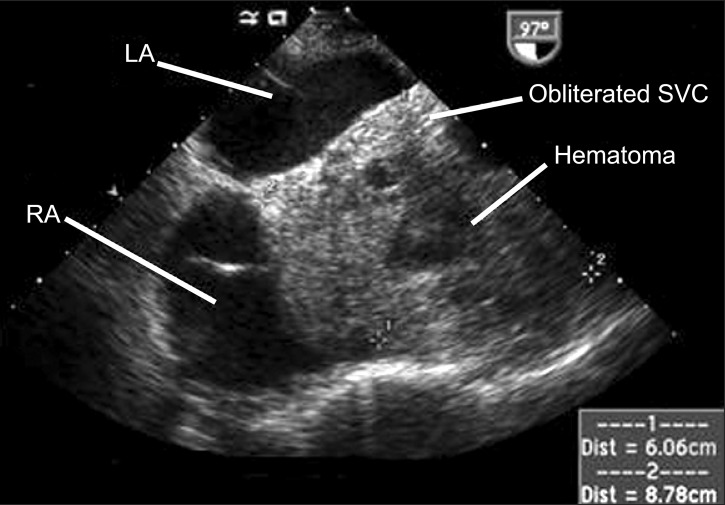

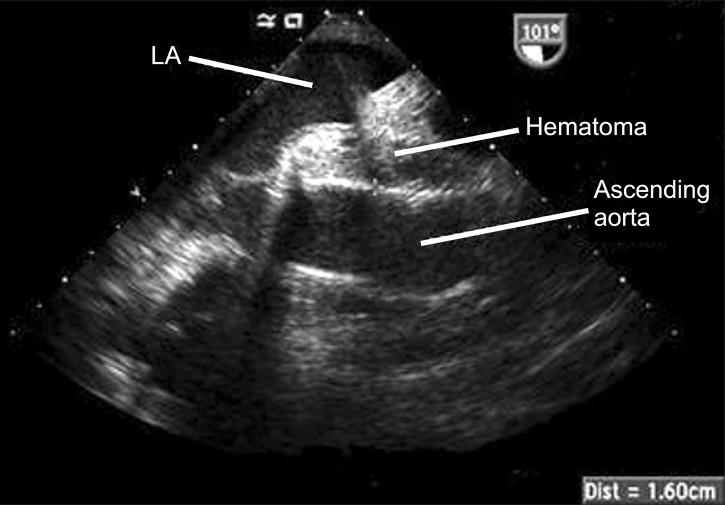

A TEE examination was immediately performed to confirm the cause of the CVP elevation, which revealed minimal pericardial fluid collection and preserved biventricular function in the midesophageal four-chamber view and the transgastric short axis view. The midesophageal bicaval view showed the right atrium (RA) being pushed anteriorly and laterally by a large mass measuring 6.06 cm × 8.78 cm (Fig. 1). The mass contained echogenic materials with some echo-free areas, which is consistent with hematoma, and as a result the SVC was almost completely obliterated by it. In the midesophageal aortic valve long axis view, the hematoma occupied the transverse sinus as well (Fig. 2). The patient was immediately transferred to the operating room for re-exploration. A loculated hematoma around the valved graft was found to compress the entire SVC and extended to the RA. After evacuation of the hematoma, the CVP decreased immediately from 23 to 11 mmHg. The cardiac index and the blood pressure remained stable despite the discontinuation of the vasopressor and inotropic agents. However, the patient's postoperative course deteriorated, with the development of acute renal failure and adult respiratory distress syndrome, which resulted in the prolongation of ICU stay. The patient was then transferred to the general ward at postoperative day (POD) 52 for rehabilitation, and discharged at POD 109.

Delayed re-sternotomy is highly associated with the worst outcomes in patients who need hemostatic re-exploration after cardiac surgery [1]. A prompt diagnosis is mandatory, but it is often challenged in the immediate postoperative period. Typical clinical features of cardiac tamponade (hemodynamic compromise with paradoxical pulse, equally elevated pressures of CVP, pulmonary artery diastolic, and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure) may be absent due to positive pressure ventilation, preexisting cardiac disease, and the involvement of a single chamber by localized effusion [2].

As demonstrated in this case report, an aortic root surgery for patients with aneurismal pathology has an increased risk in the accumulation of blood after surgery in potential spaces that had been occupied by the aneurysm, which is created by the SVC, the left atrium, and the ascending aorta. If the loculated hematoma in this space primarily affects the SVC and the adjacent RA, isolated elevations of the CVP would develop with or without a decrease in cardiac output, and consequently resulting in hemodynamic compromise [3].

In the clinical practice, the diagnosis of RA or SVC compression by a hematoma usually starts with the recognition of elevated CVP [4,5]. However, in the absence of significant hemodynamic compromise, differentiating diagnosis becomes more challenging as it usually represents the following; circulatory volume overload due to the excessive administration of fluid or acute renal dysfunction, which is fairly common in the early postoperative period. Acute or acute-on chronic RV failure is another frequent cause of CVP elevation after open heart surgery. During CPB with cardioplegic arrest, the RV is more susceptible to ischemia/reperfusion injury due to direct mechanical damage and exposure to the warm surgical light [6]. RV dysfunction may also arise secondarily from pulmonary dysfunction or acidosis, as both may increase the right ventricular afterload and the pulmonary vascular resistance. In such cases, abnormalities can be easily detected through arterial blood gas analysis, and a concomitant increase in the pulmonary arterial pressure would have been more evident than in our case. Circulatory volume overload and/or RV dysfunction are both usually amenable to medical therapy, which may delay the differential diagnosis of loculated hematoma.

In cases of an overt isolated RA tamponade, the main ECG findings were inferior or inferolateral ST depressions, along with T wave inversions with normal P waves and QRS amplitudes [7]. For these cases, the RA is almost fully obstructed, which is usually accompanied by severe hemodynamic deterioration [4,7]. Even in the absence of overt RA tamponade and hemodynamic deterioration, as in our current case, loculated hematoma compressing the SVC may be life-threatening through the formation of cerebral and laryngeal edema, as in SVC syndrome, which requires prompt re-exploration [8,9].

The importance of echocardiography for an accurate differential diagnosis of the elevated CVP cannot be overemphasized. TTE is technically suboptimal in the early postoperative period due to surgical wounds, drainage tubes, and mechanical ventilation. On the other hand, TEE provides an excellent acoustic window with better image quality in the postoperative setting. Apart from assessing ventricular functions and volume status [8], TEE is a well-established diagnostic tool for the identification of localized cardiac tamponade after cardiac surgery [4]. For this purpose, a thorough examination is mandatory as localized cardiac tamponade may be overlooked in the midesophageal four-chamber view or the transgastric short axis view, as in this case. The midesophageal bicaval view should always be examined in cases of elevated CVP in order to search for loculated hematoma or effusion. Additionally, TEE can be helpful in ruling out other rare possibilities for elevated CVP, such as acute pulmonary embolism or severe acute tricuspid regurgitation, which can be caused by the manipulation of the pulmonary artery catheter [10,11].

Compression of the SVC and the RA by loculated hematoma following cardiac surgery is a surgical emergency that must be diagnosed promptly. This case highlights the importance in recognizing elevated CVP, along with the correct differential diagnosis using TEE, even in the absence of significant hemodynamic deterioration and bleeding.

References

1. Ranucci M, Bozzetti G, Ditta A, Cotza M, Carboni G, Ballotta A. Surgical reexploration after cardiac operations: why a worse outcome? Ann Thorac Surg. 2008; 86:1557–1562. PMID: 19049749.

2. Russo AM, O'Connor WH, Waxman HL. Atypical presentations and echocardiographic findings in patients with cardiac tamponade occurring early and late after cardiac surgery. Chest. 1993; 104:71–78. PMID: 8325120.

3. Fowler NO, Gabel M. Regional cardiac tamponade: a hemodynamic study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1987; 10:164–169. PMID: 3597984.

4. Kochar GS, Jacobs LE, Kotler MN. Right atrial compression in postoperative cardiac patients: detection by transesophageal echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990; 16:511–516. PMID: 2373832.

5. Wacker J, Djaiani G, Katznelson R, Karski J. External compression of superior vena cava after the replacement of ascending aorta. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2008; 9:589–590. PMID: 18490312.

6. Gonzalez AC, Brandon TA, Fortune RL, Casano SF, Martin M, Benneson DL, et al. Acute right ventricular failure is caused by inadequate right ventricular hypothermia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1985; 89:386–399. PMID: 3974274.

7. Saner HE, Olson JD, Goldenberg IF, Asinger RW. Isolated rigth atrial tamponade after open heart surgery: role of echocardiography in diagnosis and management. Cardiology. 1995; 86:464–472. PMID: 7585756.

8. Inase N, Ichioka M, Akamatsu H, Usui Y, Miyake S, Yoshizawa Y. Mediastinal fibromatosis presenting with superior vena cava syndrome. Respiration. 1999; 66:464–466. PMID: 10516545.

9. Rabinstein AA, Wijdicks EF. Fatal brain swelling due to superior vena cava syndrome. Neurocrit Care. 2009; 10:91–92. PMID: 18704767.

10. Rosemeier F, De Wet CJ, Hantler C, Jacobsohn E. Severe acute tricuspid regurgitation after the withdrawal of an entrapped pulmonary artery catheter. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2006; 20:910–911. PMID: 17138107.

11. Pruszczyk P, Torbicki A, Kuch-Wocial A, Szulc M, Pacho R. Diagnostic value of transoesophageal echocardiography in suspected haemodynamically significant pulmonary embolism. Heart. 2001; 85:628–634. PMID: 11359740.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download