Abstract

Osteonecrosis of the humeral head is an uncommon and slow progressive condition. This condition is difficult to be recognized because its initial symptoms are nonspecific. Simple radiography is the standard tool to stage disease progression. However, plain radiographic findings of osteonecrosis are nearly normal in the initial stage. We report a case of 74 years old female patient who have suffered from painful limitation of the shoulder joint. She had no trauma history and no specific predisposing factors for osteonecrosis of the humeral head. To confirm, follow up radiography and shoulder magnetic resonance imaging were performed.

The shoulder joint is susceptible to the development of arthritis from a variety of conditions. Osteoarthritis is the most common cause of shoulder pain and functional disability. Most patients presenting with shoulder pain secondary to osteoarthritis, rotator cuff arthropathy, and post-traumatic arthritis complain of pain that is localized around the shoulder and upper arm, and progressive loss of motion.

Osteonecrosis of the humeral head is one of the causes of shoulder joint pain but not a common condition [1]. It is often unrecognized, and its symptoms are often nonspecific in its early stage. Generally, trauma is a common cause, but atraumatic necrosis has developed for patient with risk factors. The risk factors include corticosteroid administration, heavy alcohol intake, sickle cell disease, and other systemic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus [1,2,3].

In this case report, we present such a case of humeral head osteonecrosis in an elderly patient with severe painful limitation of the shoulder joint. She had no risk factors such as trauma history, steroid administration, or other chronic diseases. The etiology of rapid progression from normal radiographic findings to anatomical changes of the humeral head was unknown on this case. However, recognizing the fact that osteonecrosis is one of the causes of painful shoulder is the important for clinicians. Therefore, we report our case with a review of the relevant literature.

A 74 year-old female patient visited our pain clinic with painful limitation of motion of the left shoulder which began 3 months ago. Her visual analog scale (VAS) was 80 in 100. Physical examination was conducted. Her left shoulder range of motion (ROM) was as follows: active / passive, respectively, forward flexion (FF) 110°/150°, external rotation side (ERs) 15°/20°, external rotation abduction (ERa) 20°/60°, internal rotation abduction (IRa) 30°/50°, and abduction (Abd) 120°/130°. Her right shoulder ROM was nearly normal. The measured muscle power, right/left, respectively, was FF 2.7/0.5, ERs 1.7/0.5, IRs 1.3/1.1, Abd 2.0/0.4. Tenderness was felt in the supraspinatus, acromioclavicular joint and greater tuberosity except biceps tendon. There were no signs of atrophy or deformity. Impingement, biceps, muscle and instability tests were done, but conducting an accurate examination was difficult due to severe pain even during a small motion. Neurologic exam and simple shoulder series radiographs which were checked at another local clinic were all normal.

Her past medical history was not significant except well controlled diabetes mellitus and hypertension. She had no history of recent fall or trauma. Before she came to our clinic, she was managed conservatively with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication and physiotherapy at a local clinic, but she never received any glenohumeral intra-articular steroid injection or steroid medication according to her words. Diagnostic impression was frozen shoulder. Following this, left suprascapular nerve block of 0.25% levobupivacaine and trigger point injection (TPI) were performed. After these procedures, she felt pain relief and returned home with a 7-day medication regimen (celecoxib, afloqualone).

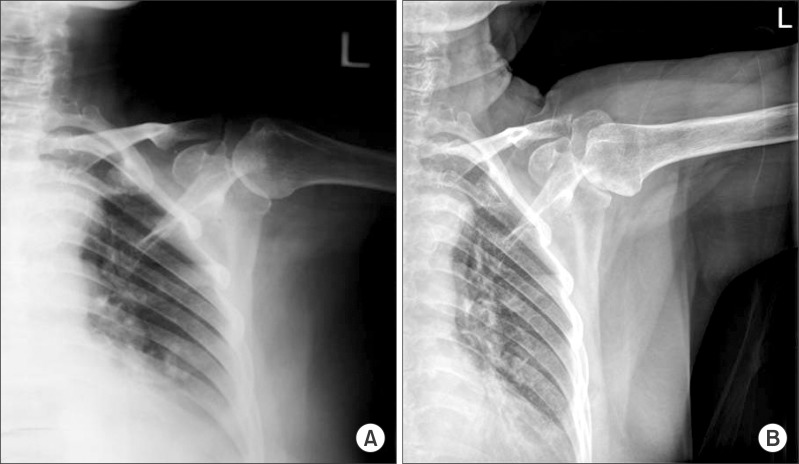

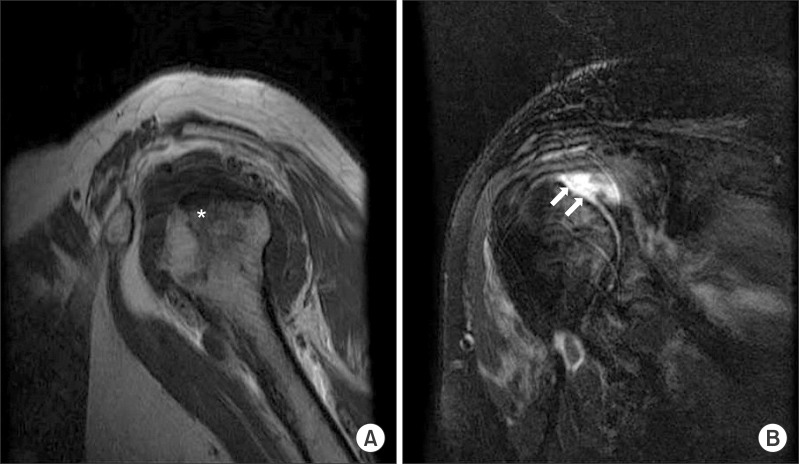

Seven days later, she visited the clinic for follow-up only to discover that her shoulder pain was not improved. To examine the tendons and muscular structures of the shoulder, ultrasound exam was conducted. However, ultrasound findings were nonspecific. To reduce her pain, sono-guided left shoulder joint injection of 0.1% levobupivacaine without steroid was performed. Left suprascapular nerve block and TPI were also done at the same sites. For further evaluation of her shoulder pain, follow up simple shoulder series radiographs and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were recommended, and she agreed. Radiologic exams were performed (Fig. 1) and suggested osteonecrosis of the humeral head. Shoulder MRI (T1- and T2-weighted images, Fig. 2) revealed partial articular side tear of the supraspinatus tendon, severe osteoarthritis with chondromalacia of the left shoulder joint, subluxation of the biceps long head tendon, subdeltoid and subacromial bursitis. The patient was transferred to the orthopedic surgery outpatient department for shoulder operation. She received left shoulder hemiarthroplasty, and the final pathologic diagnosis of her condition was osteonecrosis of the humeral head.

The humeral head is the second most commonly affected site in osteonecrosis, but not a common condition. Osteonecrosis of humeral head is often unrecognized, and its symptoms are often nonspecific in its initial stage. Osteonecrosis of the humeral head is more common in men and more prevalent among young patients between the second and fifth decades of life [4].

Some theories have been proposed for idiopathic osteonecrosis including mechanical disruption of bone blood supply [3], arterial or venous outflow obstruction [5], increased intra-osseous pressure [6], and resultant osseous cell death [7]. The theory of blood supply interruption by various initiative conditions has been commonly accepted. The proximal humerus has both intra and extra osseous blood supply. An ascending branch of the anterior circumflex humeral artery on the anterolateral aspect of the humeral head provides a major supply to the humeral head. It also receives blood supply from several anastomoses formed by the suprascapular, thoracoacromial, and subscapular arteries. An arcuate artery pursues a tortuous posteromedial course just below the epiphysis in the interosseous portion. Therefore, the subchondral bone blood supply is vulnerable to thrombus and emboli formation due to the existence of only one principal artery and the extreme tortuousness of the subchondral arterioles.

Causes of osteonecrosis of the humeral head are divided into traumatic and atraumatic. Traumatic conditions are fracture, dislocation, or surgery of the shoulder which can result in humeral head necrosis. There are many atraumatic causes of osteonecrosis of the humeral head such as corticosteroid use, excessive alcohol intake, sickle cell disease, divers' disease, and other systemic diseases [1,2,3]. Corticosteroid therapy is the most common cause of atraumatic osteonecrosis of the humeral head. Osteonecrosis caused by corticosteroids is associated with fat metabolism. An increase in the size of intraosseous fat cells leads to an increase in the intraosseous pressure [8], which may lead to osteonecrosis. Elevation of serum lipids may subsequently lead to occlusion of subchondral vessels by fat emboli [9].

Although osteonecrosis is related to chronic administration of high-dose corticosteroids, it is impossible to predict in which patients the disease will occur [9]. Hernigou et al. [10] mentioned the delay between the beginning of corticosteroid treatment and the diagnosis of osteonecrosis of the humeral head was on average 15 months. Eighty-two percentage of symptomatic shoulders and 54% of asymptomatic shoulders in patients with osteonecrosis had collapsed at final follow up. Even if they were in the early stage of the disease, spontaneous resolution was observed when the lesion was small, anterior and unilateral, or when they were no longer on steroids. The time between diagnosis and collapse was on 10 years for patients with symptomatic stage I osteonecrosis and 3 years for patients with symptomatic stage II [10]. On the other hand, the mean interval between pain onset and collapse was six months in adults with sickle cell disease (S/S genotype) [2]. Other risk factors include chronic dialysis, chemotherapy, hyperlipidemia, myxedema, pancreatitis, pregnancy, and systemic diseases, such as lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and Cushing's syndrome.

Common findings of osteonecrosis are sclerotic change, fibrosis and microfracture. Subchondral fracture, articular surface collapse, and glenohumeral arthrosis may progress in the late stage. Sclerotic change of the humeral head in plain X-ray is caused by partial absorption and deposition of bone. The main imaging modalities used in the diagnosis of humeral head osteonecrosis are standard radiography and MRI. Radiography is standard and commonly used to stage disease progression. However, MRI is more sensitive in detecting early changes in bone marrow and is more useful in diagnosing osteonecrosis of the humeral head. Bone scintigraphy is also recommended for the detection of osteonecrosis, but there is controversy regarding bone scan as a diagnostic tool [11].

The Cruess classification system, which is based on progression to collapse, is widely used to classify osteonecrosis of the humeral head [12]. Cruess modified the Ficat and Arlet system for classifying osteonecrosis of the femoral head [13]. Stage I can only be detected on MRI with no radiographic evidence. Mottled sign, sclerotic change of the superior middle portion of the humeral head, can be detected on plain radiographs in patient with stage II humeral head osteonecrosis The presence of the crescent sign which indicates subchondral fracture is the typical radiologic finding of stage III. Stage IV is characterized by progression to collapse of subchondral bone with loose osteocartilaginous bodies. Stage V is the terminal stage showing humeral head collapse and glenoid involvement [4].

In our case, severe osteoarthritis with chondromalacia of the left shoulder joint, bone marrow edema of the humeral head and glenoid with bony defect and sclerosis were seen on MRI. According to the classification system of Cruess, the lesion in our case was classified as stage IV. The findings did not exactly correspond with typical changes of shoulder joint on MRI findings.

Nonoperative treatment with exercises to preserve shoulder motion, conservative treatments or operations can provide pain relief. There are some reports of natural recovery with proper protection from vigorous activities [9]. Nevertheless, the lesion in the humeral head has no trend toward natural healing in adults. Conservative treatment with physical therapy, modification of activity, and analgesics are best treatment choices for precollapse stages I and II. Shoulder hemiarthroplasty or vascularized bone grafting is considered for stages III and IV. Total shoulder arthroplasty is the only treatment for stage V [9]. Our patient had stage IV thus hemiarthroplasty was done.

The pathogenesis, associated risk factors, and diagnosis of osteonecrosis of the humeral head in our case have not been fully understood. We did not perform radiographic examination at first visiting on our clinic because radiographic finding which checked at other local clinic was normal. However, normal radiographic findings are common in the early stage of osteonecrosis. Accordingly, unpredicted osteonecrosis may progress during that period. Therefore, it is very difficult to try to find the potential etiology in our case. Our patient denied corticosteroid use including herbal medication, chronic alcohol intake or cigarette smoking and had no specific disease history except controlled diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Due to rapid aggravation of the lesion, a malignant disease was suspected but no abnormal findings were observed. Nevertheless, rapid progressive osteonecrosis of the humeral head developed within only one and a half months.

Evaluation of MRI for all patients with painful limitation of motion of the shoulder joint is not cost-effective. However, imaging studies such as scintigraphy, MRI or even follow up simple radiography are needed to diagnose and confirm osteonecrosis when symptoms are unresponsive to series of treatments or become aggravated even with normal radiologic findings at the initial visit.

Patients with atraumatic humeral head necrosis may also have femoral head osteonecrosis. The incidence ranges between 40 and 85% [14]. In particular, corticosteroid-induced humeral head osteonecrosis has a high rate of other joint involvement of more than 90%. When a patient has symptomatic shoulder osteonecrosis, hip joint evaluation must be evaluated. Our patient had no evidence of femoral involvement.

Osteonecrosis of the humeral head remains a significant source of pain and shoulder dysfunction. Successful outcomes have been demonstrated in patients whose disease is diagnosed and treated early. Severe shoulder pain without responsive to treatment should be evaluated thoroughly and even if there are no risk factors, osteonecrosis of the humeral head can be considered as a cause of shoulder pain.

References

1. Cruess RL. Steroid-induced avascular necrosis of the head of the humerus. Natural history and management. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1976; 58:313–317. PMID: 956247.

2. Poignard A, Flouzat-Lachaniette CH, Amzallag J, Galacteros F, Hernigou P. The natural progression of symptomatic humeral head osteonecrosis in adults with sickle cell disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012; 94:156–162. PMID: 22258003.

3. Mankin HJ. Nontraumatic necrosis of bone (osteonecrosis). N Engl J Med. 1992; 326:1473–1479. PMID: 1574093.

4. Harreld KL, Marker DR, Wiesler ER, Shafiq B, Mont MA. Osteonecrosis of the humeral head. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009; 17:345–355. PMID: 19474444.

5. Hasan SS, Romeo AA. Nontraumatic osteonecrosis of the humeral head. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002; 11:281–298. PMID: 12070505.

6. Hungerford DS. Pathogenetic considerations in ischemic necrosis of bone. Can J Surg. 1981; 24:583–587. PMID: 7326619.

7. Hattrup SJ, Cofield RH. Osteonecrosis of the humeral head: relationship of disease stage, extent, and cause to natural history. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999; 8:559–564. PMID: 10633888.

8. Cushner MA, Friedman RJ. Osteonecrosis of the Humeral Head. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1997; 5:339–346. PMID: 10795069.

9. Sarris I, Weiser R, Sotereanos DG. Pathogenesis and treatment of osteonecrosis of the shoulder. Orthop Clin North Am. 2004; 35:397–404. PMID: 15271548.

10. Hernigou P, Flouzat-Lachaniette CH, Roussignol X, Poignard A. The natural progression of shoulder osteonecrosis related to corticosteroid treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010; 468:1809–1816. PMID: 19763721.

11. Mont MA, Ulrich SD, Seyler TM, Smith JM, Marker DR, McGrath MS, et al. Bone scanning of limited value for diagnosis of symptomatic oligofocal and multifocal osteonecrosis. J Rheumatol. 2008; 35:1629–1634. PMID: 18528962.

12. Cruess RL. Experience with steroid-induced avascular necrosis of the shoulder and etiologic considerations regarding osteonecrosis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1978; (130):86–93. PMID: 639411.

13. Ficat RP. Idiopathic bone necrosis of the femoral head. Early diagnosis and treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1985; 67:3–9. PMID: 3155745.

14. Cruess RL. Corticosteroid-induced osteonecrosis of the humeral head. Orthop Clin North Am. 1985; 16:789–796. PMID: 4058903.

Fig. 1

(A) An anteroposterior plain radiograph shows relatively normal findings compare to (B) which represents collapse of the humeral head and areas of necrotic bone.

Fig. 2

Magnetic resonance imaging of the left shoulder shows the characteristic involvement of a significant portion of the superior articular surface. (A) Sagittal T1-weighted image reveals bone marrow edema (*) and sclerosis of the humeral head. (B) Coronal FSE T2-weighted fat saturated image demonstrates subchondral fracture (arrows) within the humeral head as well as cortical irregularity.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download