Abstract

The airway management of patients with subglottic stenosis poses many challenges for the anesthesiologists. Many anesthesiologists use a narrow endotracheal tube for airway control. This, however, can lead to complications such as tracheal mucosal trauma, tracheal perforation or bleeding. The ASA difficult airway algorithm recommends the use of supraglottic airway devices in a failed intubation/ventilation scenario. In this report, we present a case of failed intubation in a patient with subglottic stenosis successfully managed during an i-gel™ supraglottic airway device. The device provided a good seal, and allowed for controlled mechanical ventilation with acceptable peak pressures while the patient was in the beach-chair position.

Supraglottic airway devices (SADs) play an important role in the airway management of patients with difficult airways. They allow ventilation even in patients in whom facemask ventilation and tracheal intubation are difficult. Subglottic stenosis of the trachea can cause difficult tracheal intubation. This can lead to complications such as tracheal mucosal trauma, tracheal perforation or bleeding [1]. The i-gel™ is a new single-use non-inflatable supraglottic airway device that is composed of a styrene ethylene butadiene styrene. It is a soft and thermoplastic elastomer gel. It provides a good perilaryngeal seal without cuff inflation [2]. In this case report, we describe the use of the i-gel™ for the management of ventilation in a patient with subglottic stenosis undergoing surgery in the beach-chair position.

A 50-year-old male (182.9 cm, 78.5 kg) was scheduled for arthroscopic debridement of the left shoulder. The patient had a history of old pulmonary tuberculosis and TB pleurisy (20 years ago) and had no previous surgeries. His Mallampati class was 2 and he had been NPO for more than 8 hours. He had a bull neck with limited neck extension. His thyromental distance was 6 cm and mouth opening was 4 cm.

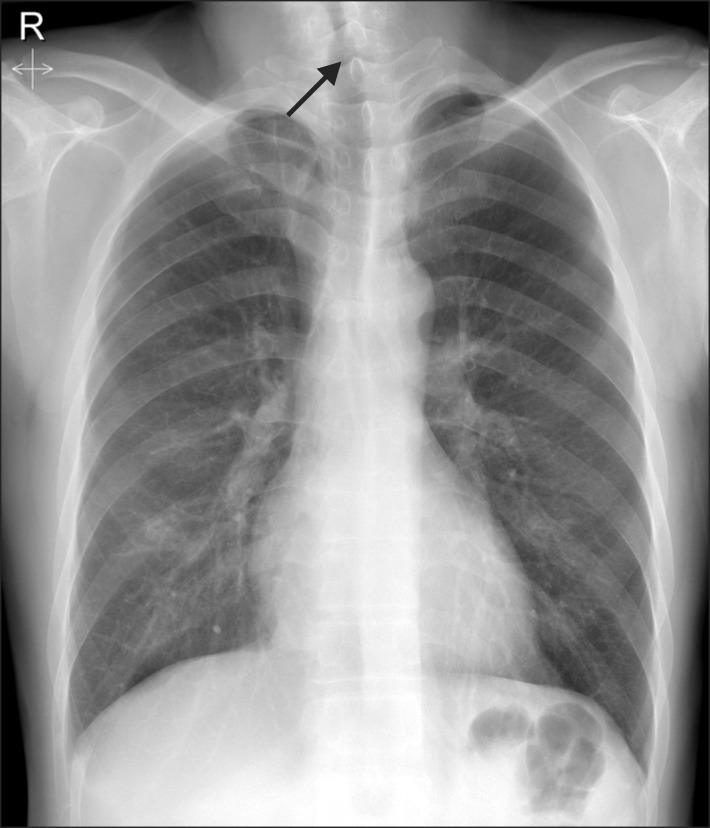

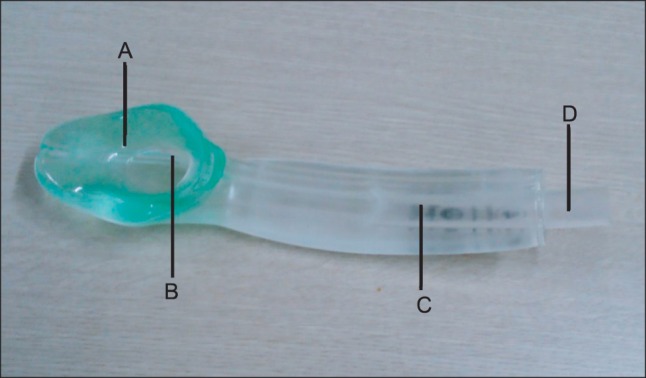

Chest X-ray (Fig. 1) showed a lesion suspicious for tracheal stenosis, but it's formal decipher by radiologist was no active lung lesion. He had no upper airway narrowing symptom and no history of endotracheal intubation. So, no further evaluation of airway have been done before surgery. In the operating room, electrocardiogram (lead II), pulse oximetry, non-invasive blood pressure, end-tidal carbon dioxide concentration (ETCO2) and bispectral index were monitored. Intravenous glycopyrrolate 0.2 mg was given as premedication. Following 3 minutes of preoxygenation, general anesthesia was induced with lidocaine 60 mg, propofol 120 mg, rocuronium 60 mg and remifentanil 0.5-1.0 mcg/kg/min. On direct laryngoscopy, Cormack and Lehane score was grade 4. We tried to insert a 7.5 mm reinforced endotracheal tube with a stylet, but this procedure failed. We then attempted to perform a blind intubation by inserting a 6.5 mm reinforced endotracheal tube with a stylet by another anesthesiologist, but we felt resistance under the vocal cords. We decided to try intubation with Optiscope PM 201™ (Video assisted system, Kyung Won medical, Seoul, Korea), but this attempt failed because a 6.0 mm reinforced endotracheal tube stopped at subglottic level. Therefore, an alternative airway device was considered. The i-gel™ (Intersurgical Ltd., Wokingham, Berkshire, UK) supraglottic airway device (Fig. 2) was chosen, and the device was inserted without difficulty on the first attempt. It was inserted blindly, until mild resistance was felt, as recommended by the manufacturer. Dexamethasone 5 mg was injected intravenously to prevent airway edema. Subglottic stenosis of the trachea was revealed by fiberoptic bronchoscopy. The patient's lungs were ventilated with a tidal volume of 650 ml at a rate of 12 breaths per minute. The i-gel™ provided a good seal, and allowed for controlled mechanical ventilation with acceptable peak pressures (12-15 mmHg) while the patient was in the beach-chair position.

The operation time was 1 hour 40 minutes and the time under anesthesia time was 3 hours. There was no leakage from the i-gel™ airway throughout the procedure. After neuromuscular recovery was demonstrated, the patient was awakened, and the i-gel™ was removed. He was discharged without significant complications on 11th postoperative day.

The airway management of patients with subglottic stenosis poses many challenges for the anesthesiologists. Many anesthesiologists use a narrow endotracheal tube. However, with this method, there is an associated risk of failed intubation. Patients sometimes suffer hypoxia because of recurrent and prolonged intubation attempts. The procedure can also lead to complications such as tracheal mucosal trauma, perforation or bleeding [1].

In some patients with tracheal stenosis, airway control might be achieved by the use of an endotracheal tube positioned above the stenosis. If the stenotic segment is in the proximal trachea, however, proper fixation of the tube is difficult [3]. Trauma, neoplasm, inflammation, Wegener's granulomatosis and prolonged endotracheal intubation are the causes of the tracheal stenosis [4]. In the case discussed here, we assumed that the cause of tracheal stenosis was TB pleurisy. His chest X-ray showed a lesion suspicious for tracheal stenosis. Radiography can be very useful, but chest radiographs can also appear normal in patients with tracheal stenosis. Computed tomography scans can be an extremely useful diagnostic tool in these patients [4]. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy may be helpful to verify for tracheal stenosis. In our case, subglottic stenosis was revealed by fiberoptic bronchoscopy, but we could not save images.

SADs can be used regardless of the location of the stenotic segment [3]. SADs have advantages such as easy insertion and high effectiveness in securing a difficult airway [5]. The use of SADs with subglottic stenosis patients has been described in the literature [3,6].

The i-gel™ is a single-use non-inflatable supraglottic airway device which is launched throughout the UK in January 2007. It is composed of styrene ethylene butadiene styrene, which is soft and covers the larynx without cuff inflation [2]. The seal pressure improves over time due to the thermoplastic properties of the gel cuff which may form a more efficient seal around the larynx after warming to body temperature [7]. When correctly inserted, the tip of the i-gel™ will be located in the upper esophageal opening. It provides a conduit via the gastric channel to the esophagus and stomach [2]. It is designed to achieve a mirror of the supraglottic anatomy (pharynx and larynx) and the noninflatable cuff is semirigid [8]. Thus risk of airway obstruction is decreased. Donaldson and Michalek [9] reported a successful use of i-gel™ for subglottic stenosis patient who was undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

The i-gel™ has an integral bite block and may decrease rotation within the oropharynx [10]. Sanuki et al. [11] suggested that the anatomic position of the i-gel™ does not vary with head and neck position and that ventilation with the i-gel™ can be effectively performed with the head and neck in the extended or rotated position.

In this report, we have presented a case of failed intubation in a patient with subglottic stenosis successfully managed with the i-gel™. We suggest that the i-gel™ is a suitable choice in situations in which endotracheal tube insertion is difficult or has failed.

References

1. Loh KS, Irish JC. Traumatic complications of intubation and other airway management procedures. Anesthesiol Clin North America. 2002; 20:953–969. PMID: 12512271.

2. Jindal P, Rizvi A, Sharma JP. Is I-gel a new revolution among supraglottic airway devices?--a comparative evaluation. Middle East J Anesthesiol. 2009; 20:53–58. PMID: 19266826.

3. Asai T, Fujise K, Uchida M. Use of the laryngeal mask in a child with tracheal stenosis. Anesthesiology. 1991; 75:903–904. PMID: 1952215.

4. Daumerie G, Su S, Ochroch EA. Anesthesia for the patient with tracheal stenosis. Anesthesiol Clin. 2010; 28:157–174. PMID: 20400046.

5. Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway: an updated report by the American Society of Anaesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology. 2003; 98:1269–1277. PMID: 12717151.

6. Szmuk P, Ezri T, Akca O, Alfery DD. Use of a new supraglottic airway device - the CobraPLA - in a 'difficult to intubate/difficult to ventilate' scenario. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2005; 49:421–423. PMID: 15752414.

7. Gabbott DA, Beringer R. The iGEL supraglottic airway: a potential role for resuscitation? Resuscitation. 2007; 73:161–162. PMID: 17289250.

8. Richez B, Saltel L, Banchereau F, Torrielli R, Cros AM. A new single use supraglottic airway device with a noninflatable cuff and an esophageal vent: an observational study of the i-gel. Anesth Analg. 2008; 106:1137–1139. PMID: 18349185.

9. Donaldson W, Michalek P. The use of an i-gel supraglottic airway for the airway management of a patient with subglottic stenosis: a case report. Minerva Anestesiol. 2010; 76:369–372. PMID: 20395888.

10. Lee JR, Kim MS, Kim JT, Byon HJ, Park YH, Kim HS, et al. A randomized trial comparing the i-gel (TM) with the LMA Classic (TM) in children. Anaesthesia. 2012; 67:606–611. PMID: 22352745.

11. Sanuki T, Uda R, Sugioka S, Daigo E, Son H, Akatsuka M, et al. The influence of head and neck position on ventilation with the i-gel airway in paralysed, anaesthetized patients. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2011; 28:597–599. PMID: 21505345.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download