This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Background

The use of monitored anesthesia care (MAC) as the technique of choice for a variety of invasive or noninvasive procedures is increasing. The purpose of this study to compare the outcomes of two different methods, spinal anesthesia and ilioinguinal-hypogastric nerve block (IHNB) with target concentrated infusion of remifentanil for inguinal herniorrhaphy.

Methods

Fifty patients were assigned to spinal anesthesia (Group S) or IHNB with MAC group (Group M). In Group M, IHNB was performed and the effect site concentration of remifentanil, starting from 2 ng/ml, was titrated according to the respiratory rate or discomfort, either by increasing or decreasing the dose by 0.3 ng/ml. The groups were compared to assess hemodynamic values, oxygen saturation, bispectral index (BIS), observer assessment alertness/sedation scale (OAA/S), visual analogue scale (VAS) for pain score and patients' and surgeon's satisfaction.

Results

BIS and OAA/S were not significantly different between the two groups. Hemodynamic variables were stable in Group M. Thirteen patients in the same group showed decreased respiratory rate without desaturation, and recovered immediately by encouraging taking deep breaths without the use of assist ventilation. Although VAS in the ward was not significantly different between the two groups, interestingly, patients' and surgeon's satisfaction scores (P = 0.0004, P = 0.004) were higher in Group M. The number of the patients who suffered from urinary retention was higher in Group S (P = 0.0021).

Conclusions

IHNB under MAC with remifentanil is a useful method for inguinal herniorrhaphy reflecting hemodynamic stability, fewer side effects and higher satisfaction. This approach can be applied for outpatient surgeries and patients who are unfit for spinal anesthesia or general anesthesia.

Go to :

Keywords: Inguinal herniorrhaphy, Monitored anesthesia care, Remifentanil, Spinal anesthesia

Introduction

It is known that inguinal hernia is the third most common disease for adults following acute appendicitis and proctological disorder in surgery. The incidence of inguinal hernia is known to increaseafter 55 years of age [

1]. The choice of anesthetic method should be decided by careful consideration of the patient's body-condition, medical history, co-morbidity with other disorders, age and surgical method. Local anesthesia has been reported to have many advantages over other methods in ways such as recovery index, medical expenses and patient satisfaction [

2,

3]. Recently, monitored anesthesia care (MAC) using local anesthesia in combination with intravenous anesthetics was performed to give the patient more comfort and safety, and led to faster recovery than general anesthesia or spinal anesthesia [

4]. MAC is usually performed with short acting hypnotics and opioids that provide excellent anxiolytic and analgesic effects. However, oversedation leading to respiratory depression was is a critical cause of patient injuries during MAC [

5]. In this research, the changes of patients' hemodynamic indices, level of sedation, side effects, and pain with the use of remifentanil without any sedatives under ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerve block (IHNB) were compared with those with the use of spinal anesthesia in unilateral inguinal herniorrhaphy.

Go to :

Materials and Methods

After approval from the local ethics committee and obtaining informed written consent from each patient, 50 American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status I-III adult patients scheduled for elective unilateral inguinal herniorrhaphy were included in this study. Those who were unable to cooperate or communicate, those with recurrent hernia, bilateral herniorrhaphy, or drug abuse history such as opioid, analgesic or sedative, and with allergic history to the drugs used in this study were excluded from the research subject. After random number generation by a computer, 50 consecutive patients were divided into two groups: spinal anesthesia group (Group S, 25 patients) and IHNB under MAC group (Group M, 25 patients). Due to obvious differences between the two types of anesthesia, neither the patients nor the anesthesiologist could be blind to the group assignment. However, on postoperative day one, the evaluating anesthesiologist did not know the performed anesthesia method in patients.

All patients did not take premedication before anesthesia and we monitored non-invasive blood pressure, pulse oxymetry, electrocardiography, bispectral index (BIS, Aspect® Medical Systems, BIS A-2000, Norwood, MA, USA) and end tidal CO2 via nasal cannula to assess the patient's respiratory rate by capnography. Six ml/kg of saline was loaded to patients in Group S before anesthetic induction. These patients underwent spinal anesthesia using the midline approach with a 26 guage Quincke needle at the L2-3 or L3-4 intervertebral space with the patient in the lateral position. After checking the free cerebrospinal flow, 10-12 mg of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine was injected. A sensory dermatome of at least T10 was judged as an appropriate sensory block level. In Group M, remifentanil was given at a dose of 1.0 ng/ml of effect site concentration (Cet) by an infusion pump (Orchestra Base primea®, Fresenius Vial, France) for 5 minutes, and then the dose was increased to 1.5 and then again to 2.0 ng/ml at 2-minute intervals before IHNB to minimize patient discomfort and respiratory depression. IHNB was performed with 30 ml of a mixture containing 0.75% ropivacaine and 1% lidocaine (1 : 1) through the oblique muscles approximately 1.5 cm medial to the anterior superior iliac crest. When necessary, lidocaine infiltration was added to the incision site. The dose was increased by 0.3 ng/ml at a time when the patient complained of discomfort during the operation. The target Cet was raised by 0.3 ng/ml at a time. In cases of respiratory depression, (respiration rate < 7 breaths/min, or apnea maintained over 15 seconds) the target Cet was decreased by 0.3 ng/ml at a time and the patient was encouraged to breathe.

Both groups were provided with 5 L/min of oxygen through simple face masks. All monitoring measurements were recorded every 2 minutes for the first 10 minutes after starting anesthesia, and then recorded every 5 minutes. When the mean blood pressure decreased over 20% of the baseline, 4 mg of ephedrine was injected. Also, BIS and observer's assessment of alertness/sedation scale (OAA/S) was checked continuously in order to monitor the sedation level. Pain level, using a visual analogue scale (VAS), and satisfaction (0-100 scores) were assessed in the recovery room after surgery. Patients were administered analgesics as needed. We visited the ward at postoperative day one and performed reassessment of VAS and satisfaction as well as postoperative side effects including urinary retention, headache, nausea, vomiting, and fever. Surgeon's satisfaction was also assessed.

All measures were displayed by mean ± standard deviation, using the SPSS 18.0 statistic program. The independent T-test and fisher's exact test were used for demographic data. The independent T-test and the paired T-test were used for mean blood pressure, heart rate, BIS and OAA/S, depending on time. The independent T-test, paired T-test, and chi-square test were used for the other variants, and P < 0.05 was judged as statistically significant.

Go to :

Results

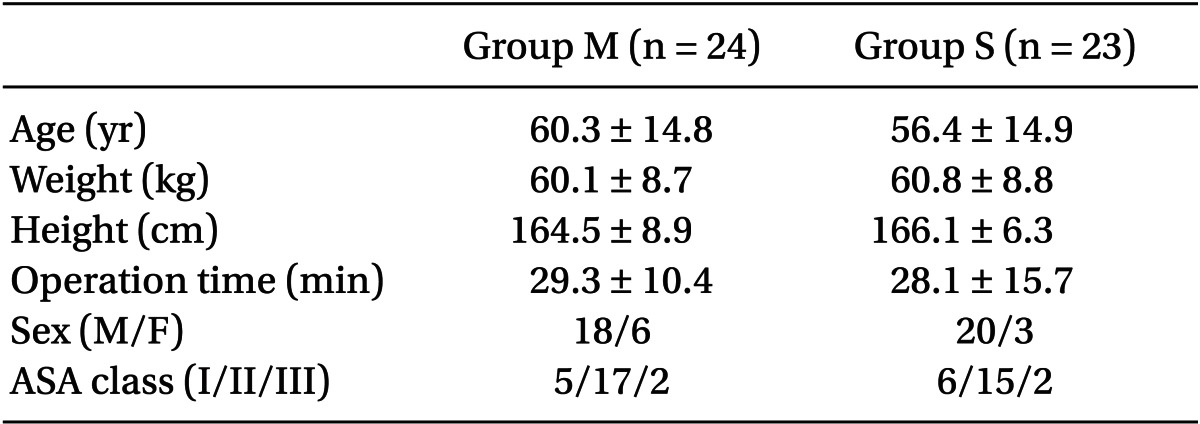

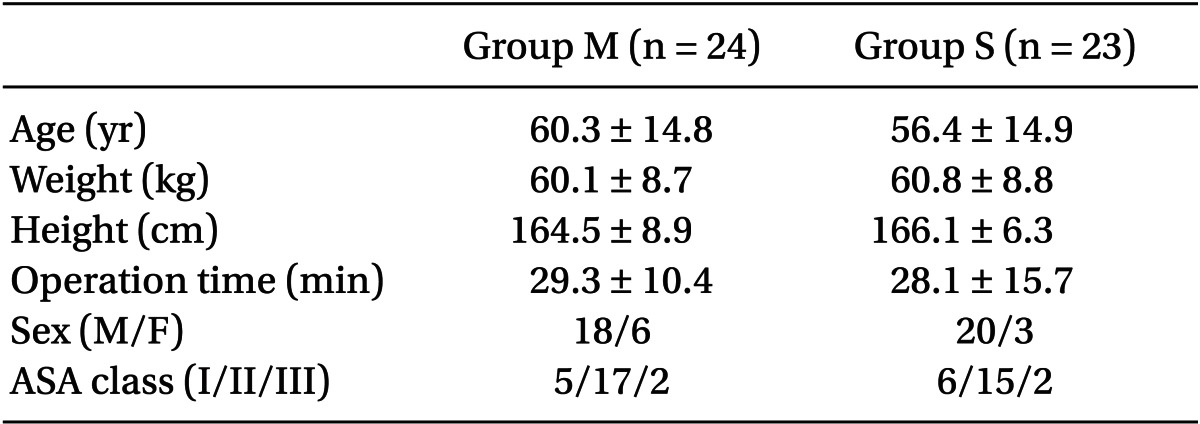

One patient in Group M wanted sedation and two patients in Group S were converted to general anesthesia; thus, they were excluded from this study. There were no differences in patients' characteristics between the two groups (

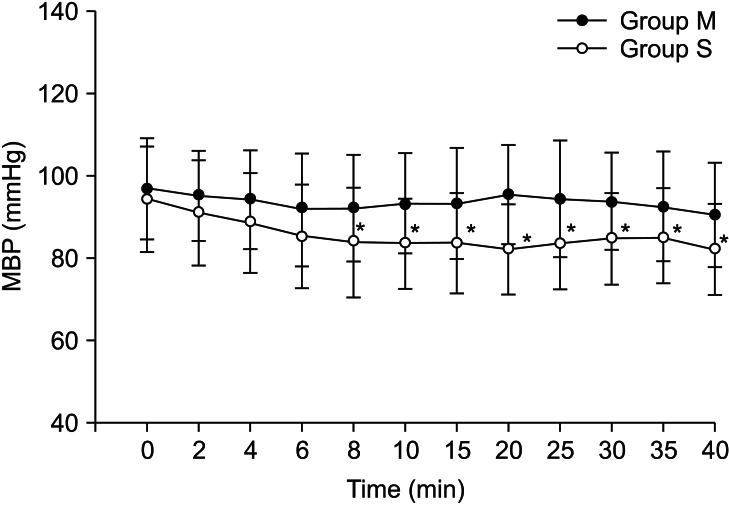

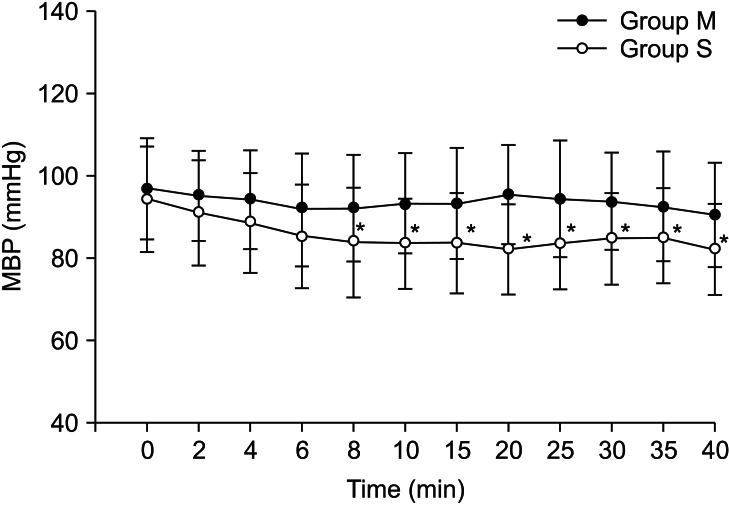

Table 1). The mean blood pressure of the patients in Group S was significantly lower than that of the patients in Group M and that of the patients before anesthesia in Group S (

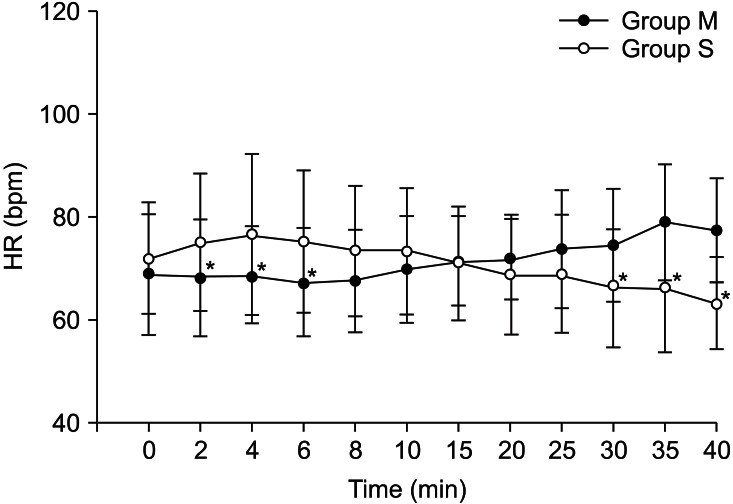

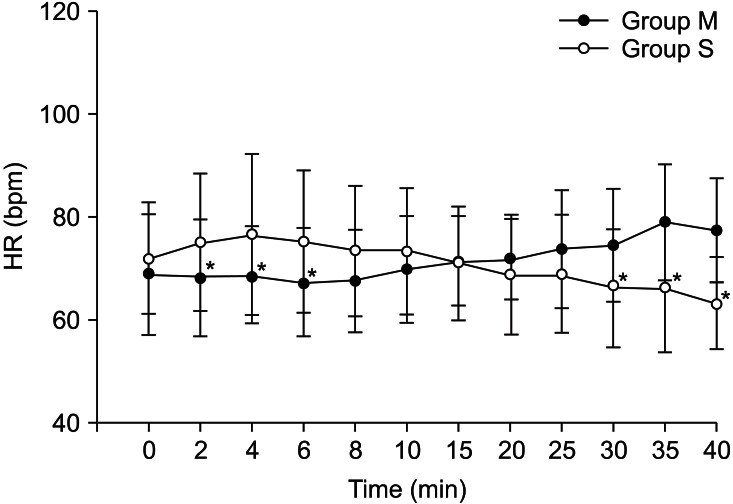

Fig. 1). Heart rate of Group M was significantly lower than that of Group S for 6 minutes after anesthetic induction; thereafter, heart rate of patients in Group S was significantly lower than that of patients in Group M after 30 minutes (

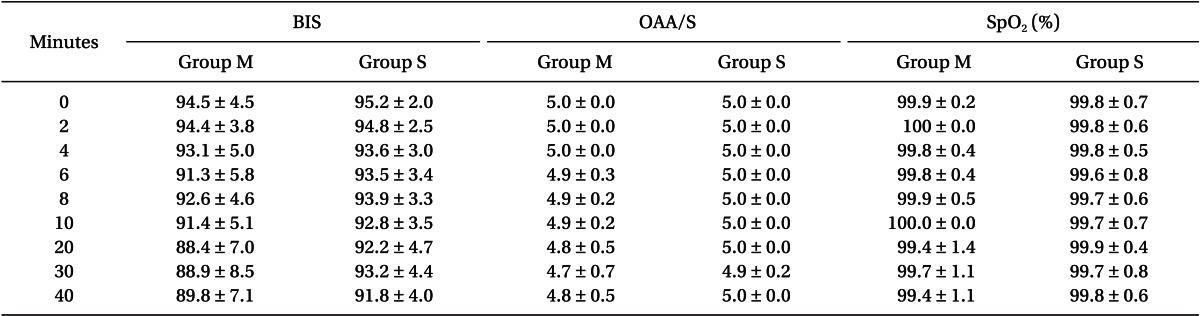

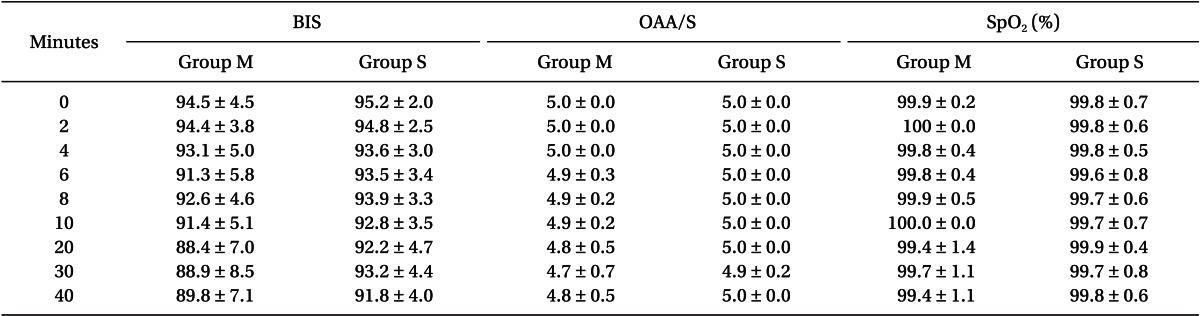

Fig. 2). There were no differences in BIS (Group M: ranged from 88 to 94, Group S: ranged from 91 to 95), OAA/S (ranged from 4 to 5 in both groups) and oxygen saturation (

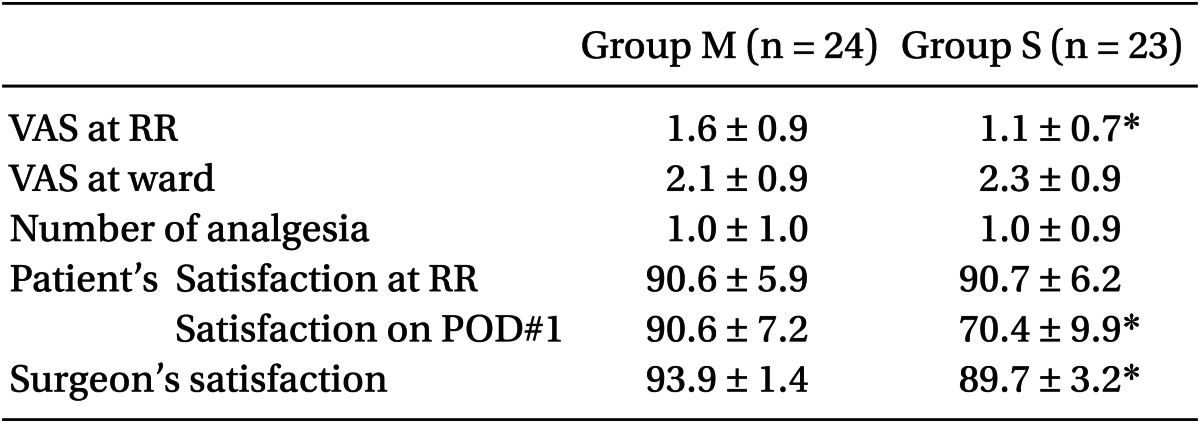

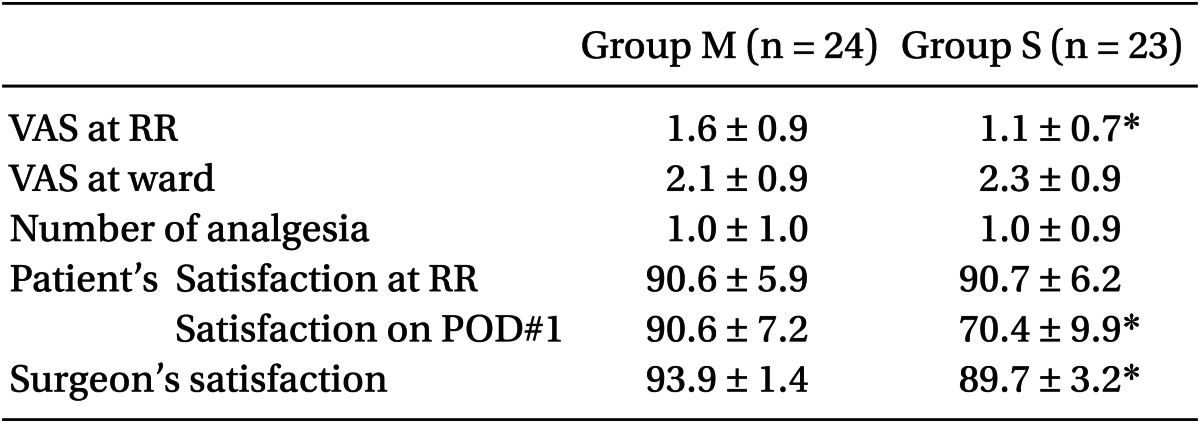

Table 2) between the groups. Although VAS of Group M in the recovery room was significantly higher (P = 0.02), there was no significant difference between the two groups at postoperative day one. There was no meaningful difference in satisfaction right after surgery, but after one day, satisfaction was significantly high in Group M (P = 0.0004) (

Table 3). Interestingly, surgeon's satisfaction was also higher in Group M (P = 0.004) (

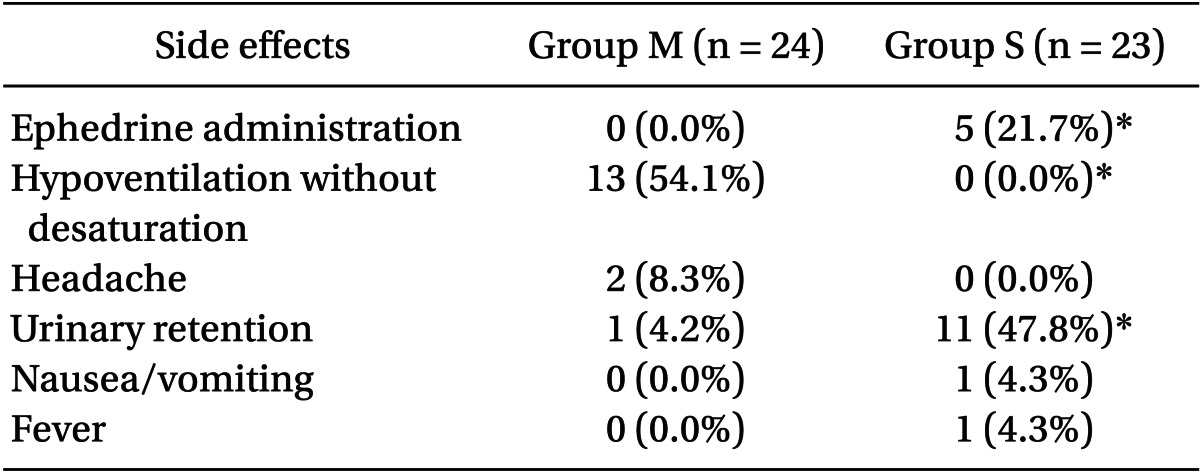

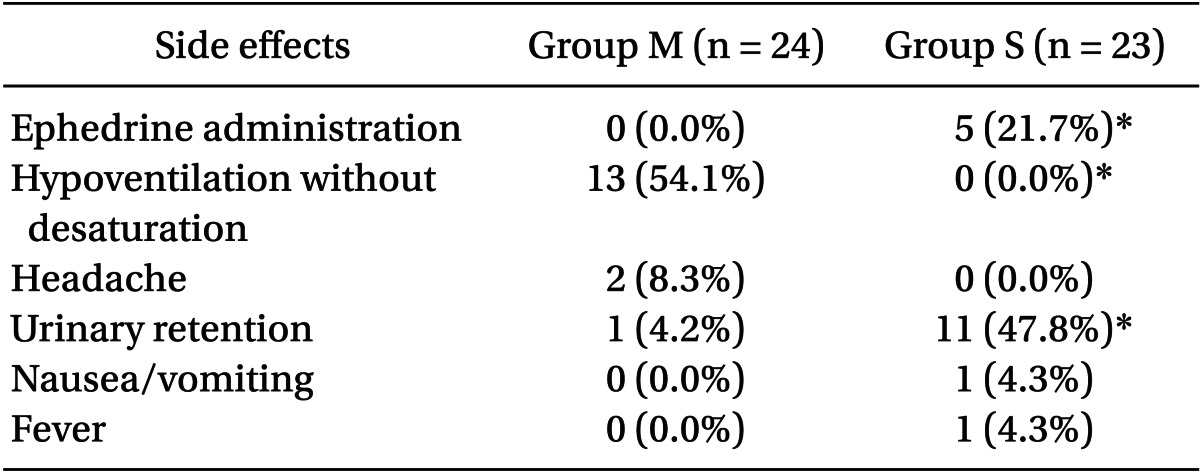

Table 3). For treatment of hypotension, ephedrine was administered to 5 patients in Group S, and none in Group M (P = 0.003). Thirteen patients (54.1%) in group M experienced hypoventilation of less than 7 breaths/min but they recovered immediately when encouraged to breathe without the use of assist (

Table 4). The number of the patients who suffered from urinary retention, 11 patients (47.8%), was significantly higher in Group S than that of Group M (P = 0.0021) (

Table 4).

| Fig. 1Changes of mean blood pressure (MBP) during anesthesia. *P < 0.05. Group M: monitored anesthesia care with ilioinguinal-hypogastric nerve block, Group S: spinal anesthesia.

|

| Fig. 2Changes of heart rate (HR) during anesthesia. *P < 0.05, Group M: monitored anesthesia care with ilioinguinal-hypogastric nerve block, Group S: spinal anesthesia.

|

Table 1

Table 2

Comparison of Sedation Scores and Oxygen Saturation between Groups

Table 3

Comparison of Postoperative Profiles between Groups

Table 4

Comparison of Intraoperative and Postoperative Side Effects

Go to :

Discussion

Inguinal herniorrhaphy is one of the most commonly performed operations in surgery. General or spinal anesthesia are usually performed but it has recently been reported that MAC using local anesthetic around the surgery spot with intravenous sedatives and analgesics has some advantages in outpatient treatment such as more rapid recovery and lower medical cost [

4,

6]. As life expectancy has improved over the decades, co-morbid diseases have also increased. However, many elderly patients live with serious underlying medical problems like cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, diabetes and renal dysfunction. In many cases, they are under various medications including antiplatelet agents. Therefore, anesthesiologists need to make careful decisions regarding the anesthetic method when faced with patients who are not able to undergo general or regional anesthesia. Due to the development of medical equipment, monitoring methods and short acting drugs, MAC is considered a useful anesthetic choice in high risk patient surgery, which can be managed using local anesthesia with additive analgesics and/or sedatives [

5,

7]. IHNB [

8] or local anesthesia [

4] has been performed for inguinal herniorrhaphy. Lim et al. [

9] carried out IHNB in young children with 72% of success rate. In the present study, IHNB was unsuccessful in one patient thus he was excluded from the study The overall success rate was 96%, which is comparable to Lim's data. Since we did not use ultrasonography guidance, the success rate would increase with the use of an imaging assist.

MAC is usually performed with short acting hypnotics and opioids, which provide excellent anxiolytic and analgesic effects. However, the use of combined hypnotics and opioids may result in respiratory depression, apnea and hypoxia [

10]. Bailey et al. [

11] described that a combination of midazolam and fentanyl significantly increased the incidence of hypoxemia and apnea in volunteers, in comparison with cases that used the drugs separately. Additive or even synergistic effects of ventilatory response to carbon dioxide on depression have been demonstrated when remifentanil and propofol [

12], alfentanil and propofol [

13] were used in combination. Bhananker et al. [

5] reported that nearly 75% of the patients who experienced injury related to sedation received a combination of two or more drugs, either benzodiazepine and an opioid or propofol plus others. Elderly patients or those who have ASA physical status of > 3 were more susceptible to the respiratory depressant effects of the sedative-analgesic-hypnotic drugs used in the study. Titration to effect by very slow administration of sedatives and opioids may be important to avoid respiratory depression in this patient population [

5]. For this reason, we chose remifentanil, since it would be more appropriate than sedatives in cases of incomplete nerve block. The initial Cet of remifentanil was 1 ng/ml for the first two minutes, and then was increased up to 2 ng/ml in order to prevent hypotension, hypercapnea, or hypoxia due to respiratory depression from excessive injection in a short time to achieve Cet. The Cet of remifentanil can be easily controlled for each level of surgical pain because it has a short context-sensitive half life, does not accumulate and provides rapid and predictable analgesia. Remifentanil is usually not used alone, but when previously used in fiber optic bronchoscopic awake intubation, it yielded excellent patient cooperation and comfort within the range of 2.4 ± 0.8 ng/ml [

14]. The concentration used in that study was similar to the concentration of remifentanil in the present study. They also reported that patients who were injected with remifentanil were more cooperative and safer than those injected with propofol [

14].

The mean blood pressure of Group S was significantly lower than that of Group M starting from 8 minutes after induction to the end of operation. It seemed that sympathetic block of spinal anesthesia reduced systemic vascular resistance. The mean blood pressure in Group M was more stable than that of Group S. Kim et al. [

7] and Kim et al. [

15] reported that they performed MAC successfully using remifentanil on high risk patients who had undertaken femoral bypass graft and inguinal hernia without hemodynamic events.

Sedation level was assessed by BIS and OAA/S. Lysakowski et al. [

16] reported that the relationship between propofol Cet and BIS was preserved with or without opioids. In the presence of an opioid, loss of consciousness occurred at a lower Cet of propofol and at a higher BIS 50 (i.e. the BIS value was associated with 50% probability of loss of consciousness), compared with placebo. This showed that opioids had an additive effect on the loss of consciousness, but little influence on BIS. There was no difference in BIS and OAA/S between their study groups. OAA/S was maintained at 4 or 5 and all patients were alert or easily awakened with soft voice or gentle tactile stimulation during the operation.

Ryu et al. [

17] reported that they used propofol and remifentanil and maintained BIS values between 60 and 80 in hysteroscopy patients, and 33% of the patients had respiratory depression who also needed maintenance of open airway and assist ventilation. Olofsen et al. [

18] discovered the relationship between remifentanil and respiratory depression using a non-steady state model. Remifentanil was administered to participants and healthy adults through continuous infusion, and showed that Cet caused 50% reduction in the amount of ventilation, yielding 1.6 ng/ml. They also reported that respiratory depression could happen at 20-50% concentration of remifentanil, that is, 1.6 ng/ml, when using propofol (1 µg/ml) with remifentanil. In the current study, the Cet of remifentanil ranged from 1.1 to 2.9 ng/ml. Respiratory depression without desaturation was detected in 13 patients from Group M when their Cet were over 2.3 ng/ml. This concentration is higher than the data mentioned above but we postulate that the patients in our study were continuously stimulated by surgical manipulation. However, there was no need for special airway management or assist ventilation because the patients were conscious, so respiratory depression was resolved by encouraging deep breaths and by lowering the Cet. In a closed claim analysis of injury associated MAC, nearly half of the claims were judged as preventable by additional monitoring. Most had pulse oximetry in use and only 20% had both pulse oximetry and capnography in use at the time of the event [

5]. We suggest that both oxymetry and capnography are essential for monitoring respiratory depression. Because single oxymetry monitoring or respiratory rate monitoring from chest movement detected by ECG could overlook the respiratory depression.

The VAS of Group M measured right after surgery was significantly higher (1.61 ± 0.89 vs 1.05 ± 0.67) than that of Group S, but clinically, the situation did not demand analgesics even though the difference was statistically significant. Another reason was that the VAS of Group S was lower due to remaining spinal anesthesia. Nevertheless, there was no difference in satisfaction between the two groups, meaning IHNB under MAC comforted patients during the operation. While the difference in VAS on postoperative day one was not significant, satisfaction of Group M was significantly higher. The outcome was contrary to the results in the recovery room. This was because patients with MAC recovered faster than those with spinal anesthesia, there was no discomfort from staying in bed for 24 hours and there were few side effects such as urinary retention Other studies have also reported that sedation with local anesthesia or MAC gave higher satisfaction than spinal anesthesia [

3,

4,

8]. Althugh sedatives and opioids were administered together in these previous studies, we had similar outcomes by using only remifnetanil in the present study.

In conclusion, IHNB under MAC with remifentanil is appropriate for unilateral inguinal herniorrhaphy. This approach resulted hemodynamic stability, faster recovery from anesthesia, fewer side effects and higher satisfaction compared with spinal anesthesia. Furthermore, IHNB under MAC is considered as a suitable anesthetic method for outpatients and high-risk individuals with serious comorbidities, for whom general or spinal anesthesia could be a risky procedure. However, it is necessary that anesthesiologists should continuously monitor the patient for occurrence of respiratory depression which can happen temporarily during surgery.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download