Introduction

The elderly population is gradually increasing, as is the proportion of elderly people in the total number of operations. As aging causes a progressive functional decline in organ systems, it is important to pay attention to underlying disease, limited end-organ reserve, stress of perioperative period [

1], and airway management in elderly patients under anesthesia.

Upper airway obstruction in an unconscious patient under anesthesia can easily occur due to the loss of pharyngeal tone and depression of the narrowed velopharynx [

2]; head extension, obtained through a chin lifting method, and endotracheal intubation are necessary to prevent this from occurring. Complications such as dental damage, airway damage, cardiopulmonary arrest, brain damage, and death can occur when management of airway maintenance, in particular endotracheal intubation, is hard to achieve [

3]. The rate of difficult endotracheal intubation has been reported by El-Ganzouri et al. [

4] as 1.0% (laryngoscopy grade 4) and by Rose and Cohen [

5] as 1.8% (more than two laryngoscopies required).

Difficult endotracheal intubation is expected in elderly patients due to degenerative changes such as dental loss and head and neck joint changes [

5-

8]. It is very important to plan for the degree of difficulty in endotracheal intubation before anesthesia, as a delay in endotracheal intubation can cause fatal consequences due to declined organ system function and comorbid conditions with aging. Rose et al. investigated the frequency of difficult endotracheal intubation according to age group and reported that the highest frequency was observed in those aged 40-59 [

5].

The current study was carried out to determine the frequency of difficult endotracheal intubation in elderly patients compared with other age groups and to examine the predictive role of basic physical characteristics and airway assessment factors.

Materials and Methods

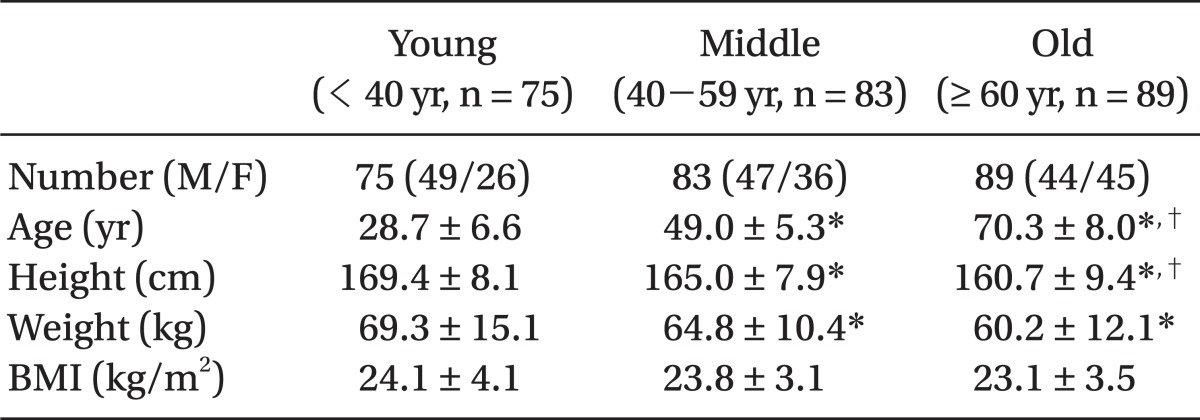

This study was initiated following approval from the hospital ethics committee and was carried out in surgical patients in need of endotracheal intubation. Participants included 247 patients who provided written consent in the period from August 2010 to April 2011. The age distribution of the study subjects was 18-92 years old, and their physical status according to the ASA classification system ranged from 1 to 3. Patients with anatomically visible deformities of the head and neck or issues with brain function were excluded from the study. There was a single investigator. Following the example of Rose and Cohen, the age groups were divided into young (less than 40 years old, n = 75), middle age (40-59 years old, n = 83), and old age (more than 60 years old, n = 89).

To assess predictive factors for endotracheal intubation according to the three age groups, patients' basic physical profiles including their age, sex, height, weight, and body mass index (BMI) were investigated. In addition, head and neck movement, thyromental distance, interincisor gap, dentition, and Mallampati score were investigated as airway assessment factors prior to the induction of anesthesia [

2,

4,

7,

9].

Head and neck movement, a method developed by Tse et al. [

10], measures the angle between the line that connects, and is also parallel between, the angle of the mouth and the tragus of the ear while the patient is lying on his or her back without a pillow. The thyromental distance was measured from the thyroid notch to the anterior border of the mandibular mentum while the patient sat down with a closed mouth and extended his or her head to the maximum extent. The interincisor gap is the distance between the incisors of the maxilla and the mandible when the mouth is opened to the maximum extent. To determine dental status, the existence of irregular dentition and lost or protruding maxilla incisors and canines were investigated, following the suggestion of Koh et al. [

7]. A dental condition with normal dentition and total anodontia was classified as grade 1; grade 2 indicated the existence of one of the dental conditions listed above; and grade 3 indicated the existence of two of the dental conditions listed above. The Mallampati score was assessed to screen the structure of the oropharynx, including the base of the tongue. This was measured while the patient was sitting down and protruding the tongue to the maximum extent [

9].

The patient was guided into the sniffing position by placing a 10 cm height pillow under the patient's head, and 100% oxygen was administered. General anesthesia was induced through intravenous administration of 1% lidocaine (30 mg), 1% propofol (2 mg/kg), and rocuronium (0.6 mg/kg). Cervical joint rigidity was then measured after muscle relaxation was confirmed by the reaction to the train-of-four stimulation on the adductor pollicis muscle. Cervical joint rigidity was classified according to the subjective impression of the head extension prior to the mouth opening during the endotracheal intubation: grade 1 was assigned for flexible status, while grade 2 was assigned for rigid status.

The endotracheal intubation was then initiated with a MacIntosh blade No. 3. Laryngoscopy was carried out, and the laryngoscopy visual field was classified according to the Cormack-Lehane (C-L) grades [

11]: grade 1 indicates 'everything visible within vocal cord area'; grade 2 indicates 'posterior arytenoids visible, some of glottic aperture'; grade 3 indicates 'epiglottis visible'; and grade 4 indicates 'no visible structure'. The numbers used for endotracheal intubation without stylette were 7.5 for males and 7.0 for females, and external laryngeal manipulation was carried out if there was difficulty in endotracheal ingression for the endotracheal intubation. The above measurements, assessment, and the endotracheal intubation were performed by a trained anesthesiologist with more than five years of experience in endotracheal intubation. The anesthesiologist carried out the study without knowing the patients' ages. Finally, the intubation time was measured by a nurse who was not involved in the study; this was predefined as the time between the laryngoscope blade coming into contact with the body and the inflation of the endotracheal tube cuff [

12].

The basic physical profiles and airway assessment factors were compared among the different age groups. A C-L grade of 1 or 2 was defined as easy endotracheal intubation, and a C-L grade of 3 or 4 was defined as difficult endotracheal intubation [

13,

14]. Differences in basic physical profiles and airway assessment factors were compared between difficult and easy endotracheal intubation, and the relative importance of the factors for difficult endotracheal intubation were examined.

Arné et al. [

15] proposed a predictive scoring method for difficult endotracheal intubation, with a score greater than 11 (between 0-48) being a predictive factor for difficult intubation. The sensitivity, specificity, rate of positive prediction, and rate of negative prediction in each group were obtained relative to difficult endotracheal intubation defined by C-L grade during the actual endotracheal intubation.

To compare basic physical status, airway assessment factors, C-L grade, and intubation time in different age groups, one-way ANOVA was carried out for the continuous variables, Tukey's test for post-hoc, and the chi-square test for discrete variables.

To analyze differences in basic physical status and airway assessment factors according to difficult and easy endotracheal intubation, the t-test was carried out for the continuous variables and the chi-square test for the discrete variables. Logistic regression analysis was carried out to determine the relative importance of the airway assessment factors in difficult endotracheal intubation, subjected to variables that were P < 0.10 in the univariate analysis, which compared difficult with easy endotracheal intubation.

SPSS (ver. 18.0 SPSS Inc. USA) was used as the statistical program, and P < 0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

Results

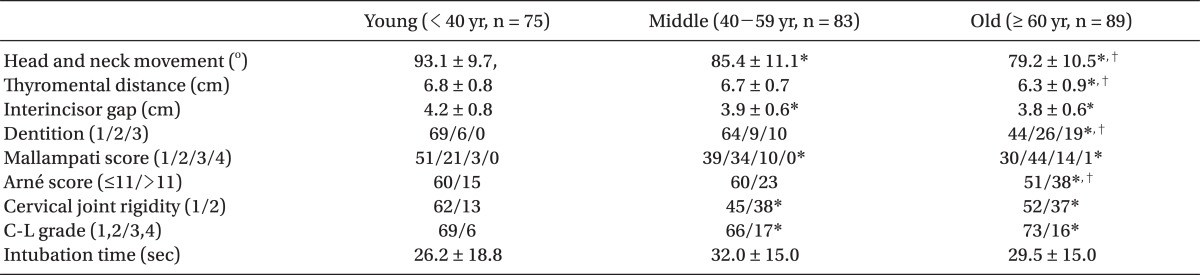

There was no significant difference in patients' BMI and intubation time according to age group (

Table 1 and

2). Patients who received external laryngeal manipulation for endotracheal intubation numbered nine in the young age group, 12 in the middle age group, and 14 in the old age group, and the number of patients in whom intubation was attempted more than twice due to a time delay in the intubation was three in the young age group, six in the middle age group, and eight in the old age group. There was no statistical significant difference between the groups.

The values for the head and neck movement, thyromental distance, and interincisor gap decreased with increasing age, and there were differences between the three groups (P < 0.05). The old age group had poor dental status relative to the other two groups (P < 0.05), and the old and middle age groups had significantly higher Mallampati scores compared with the young age group. The proportion of patients with an Arné score > 11 was highest in the old age group (42.7%). Cervical joint rigidity was greater in the old and middle age groups than in the young age group (17.3%, P < 0.05).

The proportion of patients with C-L grades of 3 or 4, which defined difficult endotracheal intubation, was highest in the middle age group (20.5%), followed by the old age group (18.0%) and the young age group (8.0%). There was a significant difference between young age group and the other two groups (

Table 2).

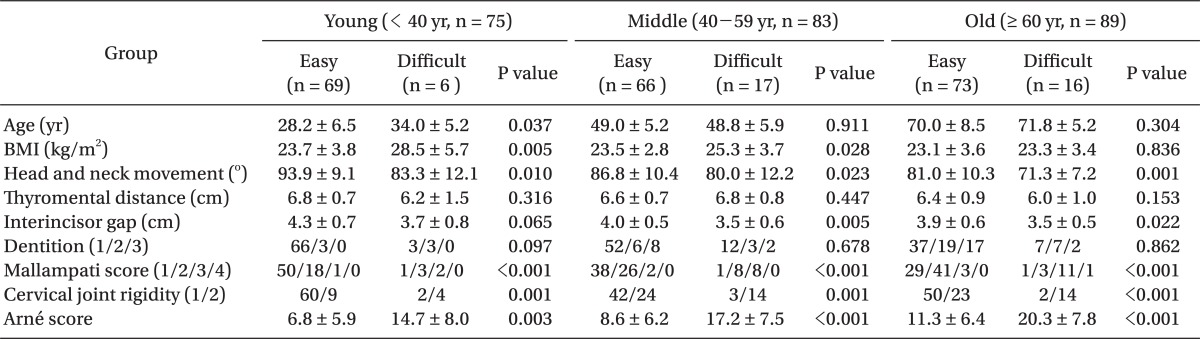

In comparing patients with C-L grades of 3 or 4 to those with C-L grades of 1 or 2 across the different age groups, head and neck movement in C-L grades 3 or 4 was significantly reduced in all three age groups, and the Mallampati score, Arné score, and cervical joint rigidity were increased (P < 0.05). The interincisor gap was small in the middle and old age groups (P < 0.05) (

Table 3).

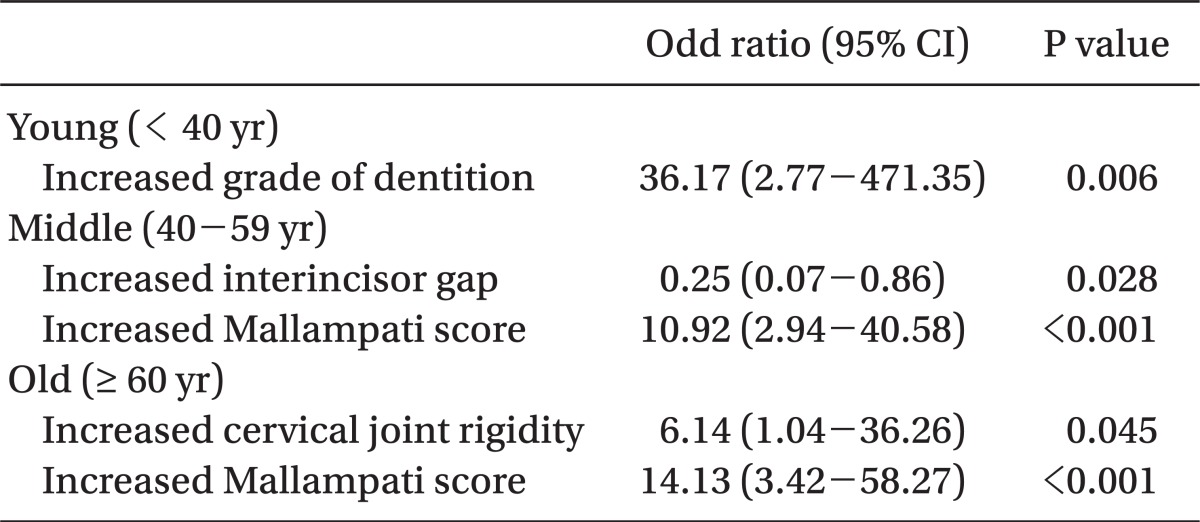

The logistic regression analysis (

Table 4) was based on the daily variable analysis shown in

Table 3 and was carried out to determine the relative impact of basic physical status and airway assessment factors on difficult intubation (C-L grade 3, 4). This analysis found that poor dental condition (odds ratio = 36.17, P = 0.006) was the main reason for difficult endotracheal intubation in the young age group, while a high Mallampati score (odds ratio = 10.92, P < 0.001) and small interincisor gap (odds ratio = 0.25, P = 0.028) caused difficult endotracheal intubation in the middle age group. The reasons for difficult endotracheal intubation in the old age group were a high Mallampati score (odds ratio = 14.13, P < 0.001) and cervical joint rigidity (odds ratio = 6.14, P = 0.045).

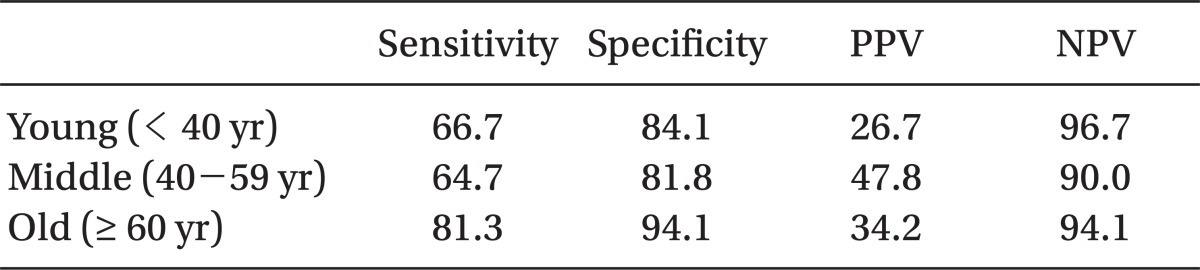

Sensitivity and specificity were the highest in the old age group, in whom the Arné score (>11) predicted difficult endotracheal intubation and actual difficult endotracheal intubation (C-L grade 3, 4) (

Table 5).

Discussion

Rose and Cohen [

5] reported that risk factors for difficult endotracheal intubation included being aged 40-59, male, and obese. The age distribution (median value: 54.7, 39.7-66.2 years) for difficult endotracheal intubation is greater than that for easy endotracheal intubation (median value: 46.5, 34.1-59.9 years) [

6]. In addition, Ezri et al. [

8] reported that laryngoscopy grades and airway classes increase with age, most likely owing to changes in bone joints and poor dental condition.

In this study, difficult endotracheal intubation (C-L grade 3, 4) across all age groups occurred in 15.8% of patients, which is a higher figure than that in previous studies: El-Ganzouri et al. [

4], Wilson et al. [

16], and Rose and Cohen [

5], reported rates of 6.1% (C-L grade 3, 4), 1.5% (C-L grade 3, 4), and 1.8% (more than two laryngoscopies required), respectively. In this study, the assessor did not have any extra support during the assessment of C-L grade, which was used as a reference for difficult endotracheal intubation. While the assessment of vision was being carried out the assessor could not continue with external laryngeal manipulation; hence, the C-L grade could have been assessed relatively highly.

The old age group had low head and neck movement, a short thyromental distance, and poor dentition relative to the middle and young age groups. Limited head and neck movement, a small interincisor gap, a high Mallampati score, and rigid cervical joints were seen more frequently in the old and middle age groups relative to the young age group. This indicates that factors related to difficult endotracheal intubation increase with age; as a result, C-L grades of 3 or 4 were more common in the middle and old age groups than in the young age group (

Table 2 and

3). There were, however, differences in height and weight between the three groups in the study, as well as differences in gender composition. Although these differences showed no statistical significance, there is nevertheless a possibility that these demographic variables could have affected the assessed values between the three groups or ultimately influenced the degree of difficult endotracheal intubation.

In the actual practice of predicting difficult endotracheal intubation, the degree of difficulty depends on complex interaction between various airway assessment factors; hence, it is more appropriate to use combined factors than to use a single factor [

4,

6,

14]. Naguib et al. [

17] proposed that a high Mallampati score (odds ratio = 12.9), short thyromental distance (odds ratio = 0.63) and small interincisor gap (odds ratio = 0.32) are predictive factors for difficult endotracheal intubation. Roes and Cohen [

5] reported that a reduced mouth opening (relative risk = 10.3), decreased thyromental distance (relative risk = 9.7), decreased neck mobility (relative risk = 3.2), and the combination of these factors allow for the prediction of difficult endotracheal intubation. Tse et al. [

10] reported a Mallampati score of 3, thyromental distance < 7 cm, head and neck movement ≤ 80°, or a combination of these factors as predictive factors for difficult endotracheal intubation.

The study also investigated the Arné score as a multivariate risk factor; Arné et al. [

15] reported that difficult endotracheal intubation is expected when seven assessment factors result in a total score greater than eleven in surgical patients, and this result has high sensitivity (94.0%), specificity (96.0%) and positive prediction (37.0%) relative to past research results [

4,

6,

16]. In this study, the proportion of patients with an Arné score > 11 was higher in the old age group (42.7%) than in the middle (27.7%) and young age groups (20.0%), and this fact explains why endotracheal intubation was more difficult in elderly patients (

Table 2). In comparison with the study by Arné et al. [

15], this study indicated lower sensitivity and specificity (

Table 5). In elderly patients, however, difficult endotracheal intubation can still be predicted more efficiently with the Arné score, as the sensitivity and specificity are relatively higher in the old age group compared with the other two groups.

Logistic regression analysis was used to indicate the impact of each factor on difficult endotracheal intubation across the different age groups, as this allows for the identification of the airway assessment factors that most affect difficult intubation, above and beyond demographic data. This suggested that it is highly possible that poor dental condition would be the reason for difficult endotracheal intubation in the young age group, while the Mallampati score is more associated with difficult endotracheal intubation in the middle age group (

Table 4).

Cervical joint rigidity, which was measured subjectively after the administration of muscle relaxant, presented with a higher grade in the old and middle age groups than in the young age group, although the objectivity was low. A high grade was also seen in patients who had difficult endotracheal intubation, and especially when this was combined with the Mallampati score, it became a cause of difficult endotracheal intubation in elderly patients. The increase in cervical joint rigidity with aging is associated with osteoarthritic disease in elderly patients and limited joint mobility in elderly patients with diabetes due to abnormal collagen connective tissue [

8,

18]. In those patients in this study with little head and neck movement prior to anesthesia, especially obese, younger patients with bulky necks, the cervical joint rigidity was decreased after administration of the muscle relaxant; thus, the head and neck movement was increased, leading to easier endotracheal intubation. Although one study reported that the increased neck circumference in obese patients can be a predictive factor for difficult endotracheal intubation [

19], muscle relaxation can have an effect, as presented in this study.

On the other hand, Givol et al. [

20] reported that dental damage during endotracheal intubation is common in patients aged 50-70 years due to periodontal disease. Dental status in elderly patients has been a particularly strong focus when considering endotracheal intubation as well as dental damage. In this study, the proportion of those with poor dental condition (grades 2 and 3) was higher in the old age group relative to the middle and young age groups (

Table 1), but, unlike in the young age group, this factor was not identified as a cause of difficult endotracheal intubation in elderly patients. Koh et al. [

7] reported that 20 out of 573 patients, despite a prediction of easy endotracheal intubation with laryngoscopy, experienced difficult endotracheal intubation in actual practice, and 15 of those patients had loss of maxillary incisors and protruding canines. In this study, laryngoscopic view (C-L grade) formed the reference for difficult endotracheal intubation. There could have been a case in which vision was secure through the space of the dental loss and the case was thus defined as an easy endotracheal intubation of C-L grade 1 or 2, even though the actual endotracheal intubation was difficult due to dental loss. Furthermore, dental status was assessed using the same reference as for dental loss, dental protrusion, and irregular dentition, and the large proportion of dental loss in the old age group and dental protrusion in the young age group were equally reflected in the dental status grades.

Intubation time was measured on the grounds that it was predicted that the more difficult the intubation, the longer this would take. There was no difference between age groups (

Table 1), and this fact can be attributed to the appropriate use of external laryngeal manipulation, the experience of the investigator, and the number of patients in the study. Adnet et al. [

12] proposed using the combined factors of the number of attempts, number of investigators, C-L grade, force used to draw out the laryngoscope, and external laryngeal manipulation rather than the simple measurement of intubation time without the process of difficult intubation. In this study, the number of cases in which external laryngeal manipulation was carried out during endotracheal intubation and intubation more than twice was greatest in the old group compared to those of the young and middle aged, but there was no statistical significance.

There are several limitations to this study: first, errors could have occurred due to the fact that the investigator, who carried out the airway assessment factor measurements, assessed on C-L grades, and performed the endotracheal intubation, was not completely blinded from the patients' ages and physical statuses. Secondly, actual endotracheal intubation can be difficult even if the laryngoscopic view is secured [

7]; on the other hand, easy endotracheal intubation can be achieved even with poor vision during laryngoscopy by using the appropriate external laryngeal manipulation and stylette, a special laryngoscopy blade. This fact highlights the need for clarification regarding the relationship between laryngoscopic view and the actual success rate of endotracheal intubation. Moreover, the statistical significance of each factor for predicting difficult endotracheal intubation would become clearer if the data were collected from more precise categories and from a larger patient sample.

In conclusion, in elderly patients (≥ 60 yr) compared with younger patients (< 40 yr), there was a decrease in head and neck movement, thyromental distance, and interincisor gap. In addition, poorer dental condition was observed, and the grades for Mallampati score and cervical joint rigidity were higher in the elderly group. In addition, there was a higher proportion of elderly patients with an Arné score greater than 11, which is a multivariate risk factor for difficult endotracheal intubation. The proportion of patients who fell into the category of difficult endotracheal intubation (C-L grade 3, 4) was higher in the middle (≥ 40 yr) than in the young age patient group (< 40 yr). The main factors implicated in difficult endotracheal intubation were poor dental condition in young patients, low Mallampati score and interincisor gap in middle-age patients, and high Mallampati score and cervical joint rigidity in elderly patients.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download