Endoscopic vein harvesting for coronary artery bypass grafting has gained increasing popularity as a minimally invasive approach to harvest venous conduits. This new technique appears to be safer, less traumatic, and more economical than conventional open vein harvesting [

1,

2]. However, massive carbon dioxide (CO

2) embolisms caused by endoscopic vein harvesting have been reported [

3-

5]. A rapid diagnosis of a gas embolism followed by prompt supportive treatment is crucial and may be life saving. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is the most sensitive tool to quickly diagnose this rare but life-threatening complication. We report a case of CO

2 embolism detected by TEE in the bicaval view during endoscopic vein harvesting that fortunately did not result in life threatening consequences.

Case Report

A 55-year-old Caucasian female was undergoing elective coronary artery bypass surgery following a recent myocardial infarction. The patient's height and weight were 168 cm and 94 kg, respectively. Intravenous midazolam was given to the patient in the holding area, and the right radial artery was cannulated. In the operating room, intraoperative monitors, included five-lead electrocardiography, pulse oximetry, a radial artery catheter, capnography (ETCO

2), and bladder temperature. Data were continuously recorded using a multichannel recorder. The patient was intubated without any difficulty after routine intravenous induction with etomidate, sufentanil, and rocuronium. The right internal jugular vein was cannulated with the patient in the Trendelenburg position, and a pulmonary artery catheter was advanced to the wedge position without difficulty. Additional monitors included a pulmonary artery catheter with venous saturation and continuous cardiac output monitoring as well as central venous pressure. An adult multiplane 6.0 MHz transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) probe (Acuson, Siemens, Washington, DC, USA) was placed. Systematic TEE images were obtained according to the American Society of Echocardiography-Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists guidelines [

6]. The TEE findings were unremarkable.

As the cardiac surgeon harvested the left internal mammary artery, the first assistant harvested the saphenous vein from the left leg via an endoscopic approach (Stryker Endoscopy, San Jose, CA, USA) using CO2 insufflation at 4 L/min and a pressure of 14 mmHg. Approximately 20 minutes after endoscopic vein harvesting started, we noticed the patient's end-tidal CO2 (ETCO2) had increased from 36 to 44 mmHg followed by increasing pulmonary artery pressure from 42/20 to 60/39 mmHg within 1 minute. Subsequently, systemic blood pressure dropped from 101/60 mmHg to 65/30 mmHg while O2 saturation remained at 100%. The cardiac index dropped approximately 15% from 2.2 to 1.9 L/min/m2, but heart rate and central venous pressure were only slightly elevated.

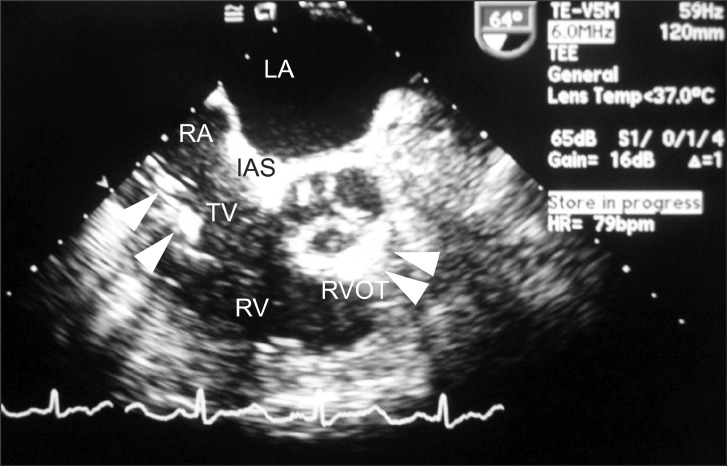

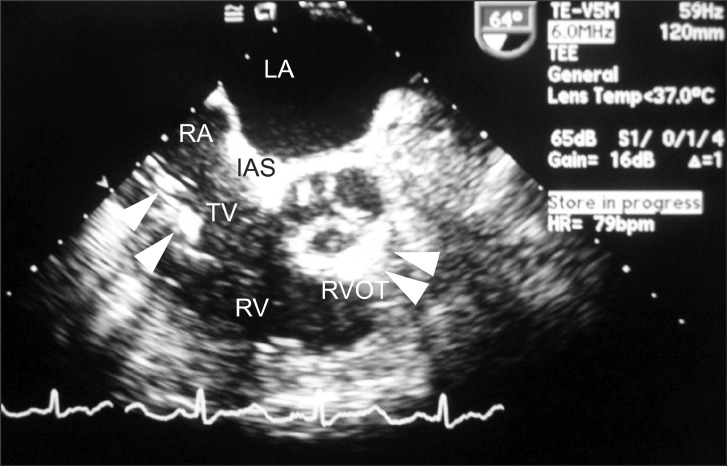

The inspiratory oxygen concentration fraction was adjusted from 50% to 100%, and vasopressors were administered to support the pressure. Mid-esophageal four-chamber and mid-esophageal aortic valve long-axis views were examined, but no new mitral or aortic regurgitation was noted. However, the mid-esophageal right ventricular inflow-outflow view revealed a massive snowflake appearance suggestive of gas bubbles from the right atrium to the right ventricle (

Fig. 1). Despite abundant gas bubbles in the right ventricular outflow, no obvious air-lock was obstructing the outflow tract. However, mild dilatation of the right ventricle was noted. At that time, all intravenous fluids through the central line were stopped, and all intravenous connections were checked to make sure no intravenous fluids were running. Despite these maneuvers, the snowflake appearance suggestive of gas bubbles was still present. We concluded that the gas bubbles were not caused from turbulence due to intravenous fluids or from a disconnected intravenous line, so a CO

2 embolism was suspected. After this observation, we kept the patient in the Trendelenburg position and increased the ventilation rate to expire more CO

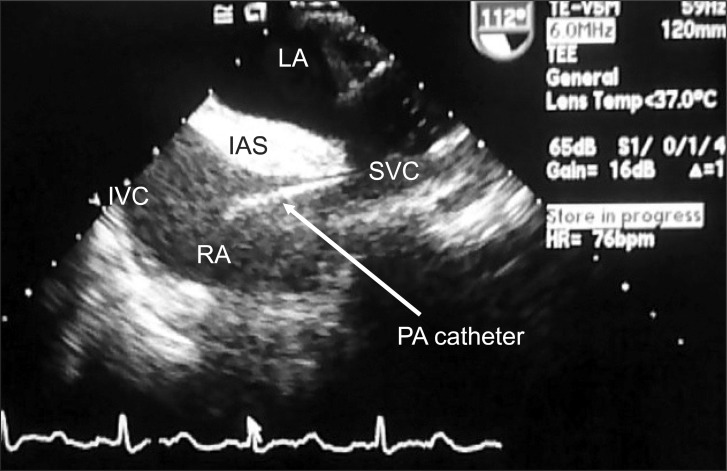

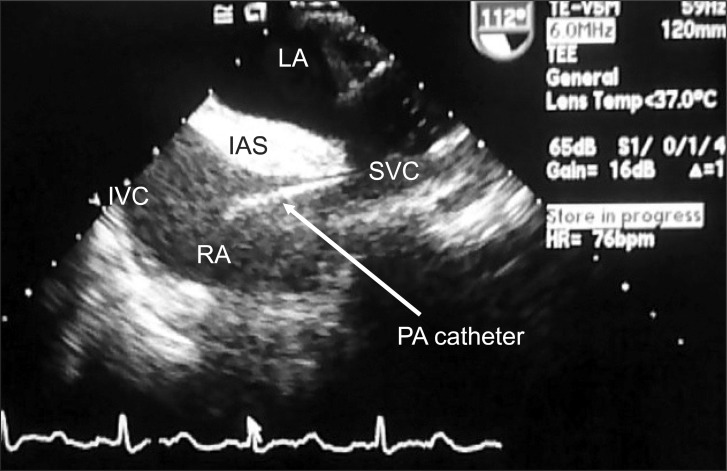

2. A nitroglycerine drip was started to lower pulmonary artery pressure, and phenylephrine boluses were administered to maintain systemic blood pressure within an acceptable range. Further examination of TEE in the mid-esophageal bicaval view revealed that the gas bubbles were originating from the inferior vena cava (

Fig. 2). Based on these findings, we concluded that the source of the gas embolism was most likely from CO

2 insufflation.

| Fig. 1Transesophageal echocardiogram, mid-esophageal right ventricular (RV) inflow-outflow view, shows a significant amount of gas in the right atrium (RA) and the right ventricle (RV) with some gas entrapment in the out-flow tract of the right ventricle (RVOT) and interatrial septum (IAS) (arrows).

|

| Fig. 2Bicaval view of the right atrium (RA) shows the pulmonary catheter in the superior vena cava (SVC) and gas entry from the inferior vena cava (IVC).

|

The surgical team was informed of these findings and they reassured us that the proximal saphenous vein was completely ligated and confirmed that most branches were adequately cauterized. The surgical team requested 5 additional minutes to complete vein harvesting based on patient stability. Our hemodynamic assessment revealed that the patient was stable, and the TEE examination revealed a significant reduction in air bubbles, so the decision was made to proceed with the endoscopic vein harvesting. Endoscopic vein harvesting was completed within the next 5 minutes. Over that course, the patient remained on 100% FiO2, and a higher ventilation rate. The nitroglycerin drip was discontinued and intermittent small epinephrine boluses were administered for inotropic support, and phenylephrine or ephedrine were administered to maintain systemic blood pressure > 90/50 mmHg.

The patient's hemodynamic status improved shortly after vein harvesting was completed, and CO2 insufflation was discontinued. We noted the patient's ETCO2 had returned back to 35 mmHg, pulmonary artery pressure had decreased steadily back to a baseline level of 40/20 mmHg, and continued down to 30/18 mmHg, whereas systemic blood pressure stabilized at 100/60 mmHg without vasopressor support. A TEE examination in the mid-esophageal right ventricular inflow-outflow view and mid-esophageal bicaval view revealed no further evidence of gas embolism. Coronary artery bypass grafting was completed without further events, and the patient recovered without any adverse neurological sequelae.

Go to :

Discussion

Our case not only confirms the vital role of TEE in the quick and accurate diagnosis of a CO2 embolism during endoscopic vein harvesting but also allowed us to focus on the mid-esophageal bicaval view, a view not commonly used to identify a CO2 embolism. Further review of the mid-esophageal right ventricular inflow-outflow view revealed that gas was entering the right side of the heart, but we could not determine whether the bubbles originated from the superior vena cava or the inferior vena cava. Using the mid-esophageal bicaval view, we were able to confirm that the gas embolism originated from the inferior vena cava, and that the lower extremity endoscopic site was the most likely suspect.

The era of minimally invasive surgery started two decades ago and has extended its influence into cardiac surgery. The first endoscopic vein harvesting was described by Lumsden et al. [

7] in 1994. The endoscopic technique is associated with a shorter time (51.07 vs. 75.94 min), better leg wound healing, and a lower incidence of wound infections (12.0% vs. 8.8%) compared to those of conventional open vein harvesting [

8]. Other advantages of endoscopic vein harvesting compared to conventional open vein harvesting include a smaller incision, less post-operative pain, a shorter hospital stay, and better cosmetic appearance [

9,

10]. The endoscopic vein harvesting procedure requires CO

2 insufflation at a flow of 4 L/min and pressure of approximately 14 mmHg to create a potential subcutaneous space. The use of CO

2 reduces vein trauma and hematoma [

11]. In contrast, there have been reports of CO

2 embolism, pneumothorax, subcutaneous emphysema, and hypercarbia [

12].

The reported incidence rate of CO

2 embolism ranges from 1-200 cases in every one million laparoscopic surgeries. The incidence of a CO

2 embolism during endoscopic saphenous vein harvesting with CO

2 insufflation procedures decreases as the severity of clinical symptoms and the volume of embolized gas increases [

4]. The incidence of venous CO

2 embolism of any size is 17.1%, whereas the incidence of massive gas emboli is only 0.5%. The incidence of a CO

2 embolism is even lower when an endoscopic approach is used to harvest arterial conduits [

13]. In our hospital, the endoscopic vein harvesting technique has been used in approximately 1,500 cases since 2005, with no reported incidence of a CO

2 embolism.

Manifestations of a CO

2 embolism include hypotension, reduced cardiac output, and decreased mixed venous oxygen saturation, along with elevated pulmonary artery and central venous pressures [

3,

4]. One of the important manifestations of an air embolism is reduction in ETCO

2. However, this sign may not be as dependable as was the case in our patient, as we observed an initial rise in ETCO

2 instead of a reduction. A drop in ETCO

2 is an indication of increased dead space and insufficient pulmonary perfusion. This condition does not generally occur unless the trapped gas in the pulmonary vascular system or the right ventricular outflow prevents blood from flowing into the lung, a condition that is generally observed with a massive embolism. Whenever CO

2 is used for endoscopic insufflation, CO

2 can directly enter the injured saphenous vein or its branches, resulting in elevated ETCO

2. Furthermore, a smaller amount of CO

2 embolized to the right heart could be released acutely, resulting in elevated ETCO

2. As was seen in our case, other investigators have previously reported elevations in ETCO

2, due to a CO

2 embolism [

14,

15].

Treatment for a CO

2 embolism includes immediate discontinuation of CO

2 insufflation, placing the patient in the Trendelenburg position, increasing FiO

2 to 100%, and aspirating the central line. The latter intervention is less successful with a pulmonary artery catheter and may divert the attention of the anesthesia team from other rescue efforts. Furthermore, inotropic agents should be started to support cardiac output to push the CO

2 embolism into the lungs [

4]. Cardiac massage and even urgent cardio-pulmonary bypass or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation have also been described if the patient does not respond to initial resuscitation efforts [

14]. In our case, we choose to allow continued CO

2 insufflation to complete saphenous vein harvesting based on the patients stabile hemodynamics and on the observation that a reduction in gas entry to the right heart occurred shortly after detecting the CO

2 embolism. This finding was interesting, as the surgical team did not reduce insufflation flow or pressure. We believe that the source of CO

2 absorption was eliminated at this point, as the surgical team cauterized the open vascular structures. The total amount of embolized gas was insufficient to cause massive cardiovascular compromise.

In summary, the use of endoscopic vein harvesting for the saphenous vein has become increasingly more common and awareness and prevention of the potential for a CO2 embolism is important. As seen in our case, TEE played a vital role in detection, and we believe that the mid-esophageal bicaval view should be used as the standard view during endoscopic vein harvesting. It has been suggested that the surgical team should pay special attention when cauterizing or ligating all vein branches to reduce the potential for CO2 entry into the venous system to prevent further CO2 embolisms. Although we allowed endoscopic vein harvesting to continue after confirmation of the CO2 embolism with direct inspection of the saphenous-femoral vein junction and meticulous closure of the tears were confirmed, further investigation into the safety of this practice is warranted.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download