Introduction

The use of opioids aid in blocking adverse reactions derived from strong external stimulations during surgery, stabilizing vital signs and decreasing doses of inhalant or intravenous anesthetics. However, not only do complications such as bradycardia and hypotension occur, but delayed postoperative awakening and ventilatory suppression result due to the drugs long duration time, making opioid use problematic.

Remifentanil, which is a selective µ-opioid agonist, has rapid onset and a short acting period and, thus is useful in inducing sedation during general anesthesia for surgery or in the emergency room. Because it is catabolized by non-selective esterases which are widely distributed throughout the blood or tissue, clearance rate is high and hardly any retention is detected when discontinued. Elimination highlife is 3-5 minutes, so despite continuous infusion or the total dosage administered, its effects are quickly lost, decreasing risks of delayed postoperative awakening or ventilatory suppression [

1].

Recently, the question as to whether the use of opioids make postoperative pain control difficult due to induction opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) has been raised. Several studies claim that the use of remifentanil during surgery induces OIH and opioid-induced tolerance, increasing postoperative pain and the use of postoperative opioids after surgery [

2-

4]. Also, the shorter the acting period of the opioid, such as remifentanil, the more rapidly and frequently hyperalgesia occurs [

5].

OIH and opioid-induced tolerance is known to be centrally sensitized through activation of NMDA receptors [

6]. Central sensitization occurs through a sequence of modulations from the dorsal horn of the spines, releasing glutamate, aspartate, and substance P from excitatory synapse membranes. These substances then activate postsynaptic NMDA receptors, increasing intake of the secondary messenger Ca

2, inducing central sensitization. Ketamine is a non-competitive NMDA receptor antagonist which blocks central sensitization by inhibiting activation of excitatory amino acids such as glutamate on NMDA receptors [

7].

A single continuous infusion of 0.25-0.5 mg/kg ketamine, or preoperative and intraoperative continuous infusion of ketamine at a rate less than 20 µg/kg/min can be used effectively during surgery because it decreases side effects, such as nightmares or hallucination, when used for pain control or analgesia [

8,

9].

We studied the effects of a continuous infusion of low dose ketamine on postoperative pain and the amount of postoperative opioids used in patients undergoing laparoscopic obstetric surgery anesthetized with sevoflurane and remifentanil.

Materials and Methods

40 female patients classified as ASA 1 or 2 scheduled for laparoscopic gynecologic surgery under general anesthesia were the objects of study. Patients with a history of drug abuse, renal or hepatic diseases and those taking analgesics were excluded. After acknowledgement from the hospital's ethics committee, informed consent was received after full description of the study and its methods.

All patients were premedicated with 2 mg of midazolam and 0.2 mg of glycopyrrolate intramuscularly and 20 mg of famotidine intravenously 30 minutes before arriving to the operating room. In the operating room, basic non-invasive monitoring of baseline blood pressure, echocardiogram and saturation were measured, along with BIS after application of the sensor to the forehead.

Anesthetic induction was conducted using 1.5 mg/kg of propofol and remifentanil with an effect site target concentration of 4.0 ng/ml using an Orchestra Pump (orchestra infusion workstation, Fresnius Vial, France). After goal concentration was attained and loss of consciousness confirmed, 0.6 mg/kg of rocuronium was administered for muscle relaxation. Ninety seconds after bagging, tracheal intubation was performed.

Patients were randomly allocated into two groups according to which treatment they were to be administered during surgery. The ketamine group (group K, n = 20) was injected with 0.3 mg/kg of ketamine during induction and continuously infused with 3 µg/kg/min of ketamine during surgery. The control group (group C, n = 20) was injected and infused with normal saline at the same volumes as the ketamine group.

Anesthesia was maintained with vital signs within a 20% range from baseline and BIS was maintained between 40 and 60. Remifentanil was maintained at an effect site concentration of 3-4 ng/ml and sevoflurane was inhaled at 1.5-2 vol%.

Ten minutes before surgery ended, PCA (Pain Management Provider, Abbott, USA) was initiated with a 120 ml mixture containing 40 mg of morphine sulfate, 120 mg of ketorolac, and 12 mg of ondansetron. Loading dose was set at 3 ml, with a continous infusion at 1.5 ml/hr and additional doses of 1.5 ml with a lockout time of 15 minutes. In the recovery room, if the patient sought more pain control or if VAS was above 4, a trained nurse administered additional dosages from the PCA.

After suturing of the skin, infusion of ketamine or normal saline was discontinued, along with sevoflurane and remifentanil. Ondansetron (4 mg) for antiemetic effects was administered. When BIS was above 80, with sufficient self respiration and eyes opening on command, the patient was extubated. The time from when the drugs were discontinued to when the patient was transferred to the recovery room was recorded.

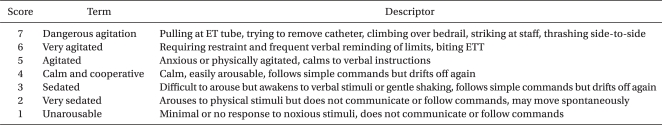

At 20 minutes intervals for 1 hour in the recovery room, at 90 minutes, then 2, 3, 4, and 7 hours post operation, the degree of pain, nausea/vomiting, nightmares and hallucinations along with the total amount of opioids used were measured. VAS (visual analogue scale) was used to measure the degree of pain and consciousness was evaluated using the Riker sedation-agitation scale (

Table 1).

All measurements were shown as mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS (version 15.0, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). An unpaired t-test was used to compare endpoints for the two groups and results were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.

Results

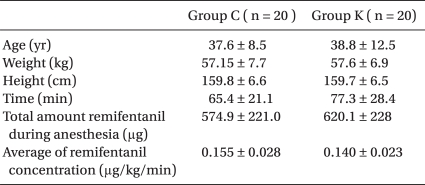

No significant differences in the demographic data were evident among the two groups (

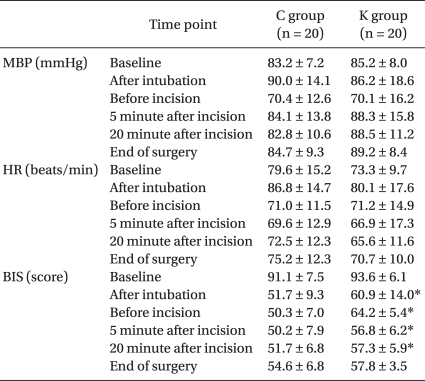

Table 2). Mean blood pressure and heart rate during surgery were not significantly different between the two groups. BIS was higher in the K group right after intubation, before incision as well as 5 and 20 minutes after incision (

Table 3).

Postoperative nausea and vomiting occurred in 1 patient in group C in the recovery room and in 1 patient in the ward. For group K, 1 patient experienced nausea and vomiting in the recovery room in addition to 2 patients in the ward. However, there were no significant differences between the two groups. Patients in group K did not experience of hallucinations or nightmares. There were no significant differences based on the time from drug discontinuance until being transferred to the recovery room between groups K (11.3 ± 2.7 min) and C (10.8 ± 2.8 min).

All patients scored 3-4 points according to the Riker sedation-agitation scale, thus no one showed signs of sedation.

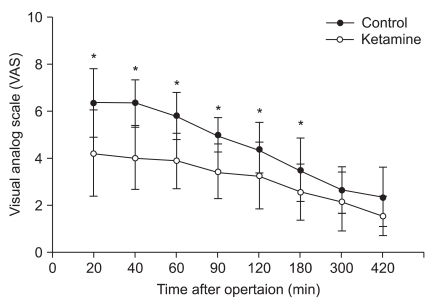

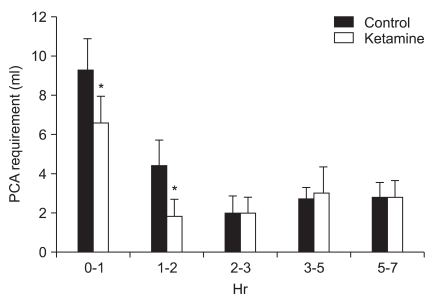

VAS scores overall were lower in the K group, and there were substantial differences within 3 hours after surgery (

Fig. 1). When the demand for opioids were divided into intervals according to time, i.e. 0-1 hour and 1-2 hours after surgery, there were significant differences, but not after 2 hours post surgery (

Fig. 2).

Discussion

Throughout this study, we were able to confirm that continuous infusion of a low dose ketamine decreased early postoperative pain caused by hyperalgesic sensitivity from remifentanil infusion in addition to a decreased use in the total amount of opioids used for analgesia.

Because remifentanil is known for its short acting period, it lacks side effects such as delayed consciousness, but rapid recovery causes problems such as acute tolerance and hyperalgesia resulting in postoperative pain. Postoperative pain increases the usage of opioids thus increasing side effects caused by these drugs. Therefore, the use of remifentanil during anesthesia should be carefully considered for postoperative pain.

Several studies state that using remifentanil causes acute tolerance or hyperalgesia. Cho et al. [

10] showed that when anesthetized with sevoflurane during obsteteric surgery, combined anesthesia with remifentanil increases early postoperative pain. Guignard et al. [

2] found that in patients receiving colon and rectal surgery, the more reminfentanil used increased the demand for opioids for analgesia 24 hours after surgery. In a study with volunteers, when 3-4 ng/ml of remifentanil infused for 60-100 minutes was discontinued, the area of capsaicin-induced hypersensitivity was inhanced over 180% [

11], and 0.1 µg/kg/min of remifentanil infused for 90 minutes expanded the area of electricity-induced skin hypersensitivity within 30 minutes [

4].

OIH is produced by lowering the threshold below basal levels and in order to achieve similar analgesic effects during acute tolerance, more opioids are needed. Thus, hyperalgesia means an increased sensitivity to pain and tolerance means a decreased sensitivity to opioids [

12]. Hyperalgesia and acute tolerance activates NMDA receptors which creates neuronal plasticity and induces central sensitization. Also, descending facilitation through opioid sensitive on-cells of the rostral ventromedial medulla and direct activation on hyperalgesic sensitivity through spinal dynorphin secretion is involved [

6].

Although the mechanism of remifentanil on NMDA receptors is still controversial, remifentanil differs from other opioids such as fentanyl by acting directly on NMDA receptor subunits. Tyrosine phosphorylation of NMDA receptor 2B (NR2B), which acts as a key role in signal transduction for activating NMDA receptors, plays a role in remifentanil-induced hyperalgesia [

13]. Remifentanil (Ultiva®, GlaxoSmithKlien, Italy) contains glycine as a vehicle. Glycine is inhibitory in the spinal cord, but when bound with glutamate on the NMDA receptors, it aids in NMDA receptor activation [

14].

Joly et al. [

15] stated that because acute tolerance and hyperalgesia was observed when high doses of remifentanil (0.40 µg/kg/min) was infused, establishing a proper dosage of remifentanil during surgery is important. Guignard et al. [

16] also reported that continuous infusion of ketamine decreased the dosage of remifentnail infused for maintaining anesthesia as well as lowered the overall amount of remifentanil used, thus decreasing hyperalgesia. However, in experiments with healthy individuals producing hyperalgesia by continuously infusing an effect site target concentration 2 ng/ml of remifentanil or at concentrations in our study, early postoperative pain was increased. The conclusion was that a 3-4 ng/ml effect site target concentration of remifentanil is adequate to induce hyperalgesia [

17].

In mastectomy or scoliosis surgery, ketamine administered prior to surgery did not have any effects on postoperative pain control or the total amount of opioids used [

18,

19]. However, in major operations such as these, noxious stimulation during surgery continuously exists and its effects are prolonged well after surgery. Therefore, it is almost indisputable that prior administration of low dose ketamine is unable to block continuous noxious stimuli. Although higher doses of ketamine may control pain better than lower doses of ketamine [

20], side effects such as hallucinations or nightmares appear more frequently, thus limiting its value [

8]. Our study was restricted to those only receiving laparoscopic obstetric surgery in order to limit noxious stimuli from tissue damage [

21].

Anesthetics may also affect OIH. Shin et al. [

22] reported that continuous infusion of propofol & remifentanil decreased VAS and the use of opioids after surgery was far less when compared to the use of sevoflurane and remifentanil. Also, postoperative pain and the use of morphine a day after surgery were overall decreased when patients were anesthetized with fentanyl & propofol as compaired to isoflurane [

23]. Propofol suppresses NMDA receptor subunits of the glutamate receptor [

24], and in order to identify the anti-analgesic effects of ketamine which is an NMDA receptor antagonist, TIVA with propofol may confuse the interpretation of our results and therefore was not used. For that reason, sevoflurane was used as the anesthetic in our study. Studies investigating remifentanil-induced hyperalgesia with sevoflurane as the anesthetic is limited. Kudo et al. [

25] stated that sevoflurane dose dependently antagonizes NMDA receptors, but recent studies report that clinical concentrations of sevoflurane are not enough to prevent the antinociceptive effects from noxious stimulation or high dose fentanyl-induced hyperalgesia [

26].

Infusion of low dose ketamine and BIS scores may also be affected by the anesthetic method. Some studies showed that TIVA with propofol and remifentanil do not affect BIS when infusing a low dose ketamine [

27], while Hans et al. [

28] reported that anesthesia with sevoflurane increased BIS. In our study, BIS was higher in group K than C group, but both were within the range of general anesthesia.

In our study, in order to compare early postoperative pain, data were collected within 7 hours post operation. Cho et al. [

10] reported that patients undergoing obstetric surgery under sevoflurane and remifentanil anesthesia, patients infused with remifentanil in the first 60 minutes of surgery complained of postoperative pain but showed no significant difference in the use of postoperative opioids. In our study, patients infused with a similar concentration of remifentanil (3.1 ± 1.2 ng/ml) complained of hyperalgesia which was most severe 4 hours after cessation of remifentanil [

11]. Therefore, further pain beyond that time period was thought to be due to surgical sitmulations [

6]. Also, regarding reports on higher infusion of opioids worsening OIH [

15], our study estimated that infusion of a relatively low dose of 0.15 µg/kg/min of remifentanil created less postoperative hyperalgesia than studies infusing higher doses of remifentanil.

Currently, ifenprodil, a drug which acts selectively on NMDA receptor NR2B subunits, lacks psychomimetic side effects such as hallucinations or nightmares compared to the nonselective NMDA antagonist ketamine [

7,

29]. Therefore, applying this drug to the OIH field should be considered. Also, local injections rather than systemic administration of ketamine may decrease complications while controlling pain, which makes further clinical studies necessary [

30].

The limitation of this study was that only two groups were compared, making the determination of the most effective dose of remifentanil and ketamine impossible. Thus, further studies in other settings are needed. Also, propofol which was used during induction of anesthesia can affect OIH, but since its use was similarly included in both groups during induction, we were able to eliminate its effects. However, in order to study antinociceptive hypersensitivity effects of ketamine alone, the use of inhalant anesthetics should be taken into consideration when choosing the method of induction of anesthesia.

In conclusion, in patients undergoing laparoscopic obstetric surgery using sevoflurane and remifentanil as the anesthetic method, early postoperative pain is increased. However, if a low dose of ketamine is continuously infused, early postoperative pain and the use of postoperative opioids was decreased. Not only should hyperalgesia and acute tolerance, which increase pain, be considered when using remifentanil, but also efforts to prevent these phenomena are warranted.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download