Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to measure lumbar epidural pressure (EP) during the insertion of a Tuohy needle under general anesthesia and to evaluate the influence of airway pressure on EP.

Methods

Lumbar EP was measured directly through a Tuohy needle during intermittent positive pressure ventilation in fifteen patients. Mean and peak EP were recorded after peak inspiratory pressures (PIP) of 0, 15, and 25 cmH2O.

Results

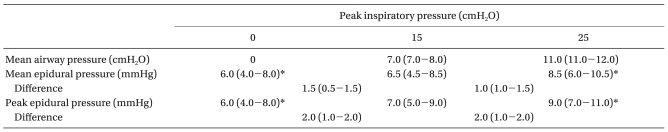

All measured lumbar EPs were positive, with the pressure increasing during inspiration and decreasing during expiration. Median EP was 6.0 mmHg (interquartile range, 4.0-8.0) at 0 cmH2O of PIP, 6.5 mmHg (4.5-8.5) at 15 cmH2O, and 8.5 mmHg (6.0-10.5) at 25 cmH2O, increasing significantly at 15 cm H2O PIP, and further increasing at 25 cmH2O (P < 0.001).

The loss-of-resistance (LOR) technique is widely used to identify the epidural space (ES). However, LOR is subjective and thus not always reliable. To improve the success rate of this technique, it has been recommended that the thoracic ES should be accessed during inspiration in patients with spontaneous ventilation, as deep inspiration expands the thoracic ES leading to decreases in epidural pressure (EP) [1,2]. However, positive pressure ventilation may affect EP.

Previous studies suggest that changing airway pressure [e.g., during application of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) or continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP)] can affect EP. Some authors have reported increases in EP with increasing airway pressure [3,4], whereas others have found airway pressure does not significantly affect EP [5]. However, in these previous studies, EP was measured through the indwelling epidural catheter. The aim of this study was to evaluate the influence of airway pressure on lumbar EP measured during insertion of a Tuohy needle under general anesthesia.

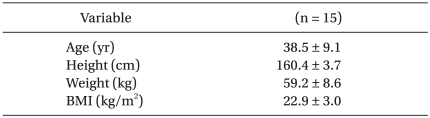

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board. 15 female patients, aged 22 to 56 years with ASA physical status I-II, who were scheduled to undergo open hysterectomy or other major gynecologic surgery under general anesthesia with lumbar epidural analgesia for postoperative pain control (Table 1) were recruited for this study. Exclusion criteria were patient refusal, pregnancy, neurologic or neuromuscular disease, coagulopathy, skin infection at the site of needle insertion, and previous spinal surgery or history of back pain. All patients gave written informed consent.

Patients received no premedication. Routine monitoring of blood pressure, electrocardiogram (ECG), and pulse oximetry was performed. Anesthesia was induced with propofol and remifentanil using a target-controlled infusion system (Orchestra® Base Primea, Fresenius Vial, France). Rocuronium (0.6 mg/kg) was injected to facilitate tracheal intubation. Anesthesia was maintained with propofol and remifentanil and a mixture of oxygen and air adjusted to maintain inspiratory O2 at 50%. Neuromuscular blockade was maintained with rocuronium. Mechanical ventilation was conducted using the S/5 Avance (GE Healthcare, Madison, WI, USA) pressure-controlled ventilation system. Peak inspiratory pressure (PIP) was set to 15 cmH2O, and respiratory rate was set to 10 breaths per minute with an inspiration to expiration time ratio of 1 : 2.

The L2-3 or L3-4 interspace area was used as a landmark for the ES. An 18-gauge Tuohy needle (Arrow International Inc., Reading, PA, USA) was inserted with the patient in the lateral decubitus position. ES identification and EP measurements were performed using a pressure transducer as described by Okutomi et al. [6]. After insertion of the needle (with stylet) into the supraspinous ligamentum, the stylet was removed. The needle was then filled with saline and connected to a pressure transducer via an arterial line extension tube filled with sterile saline. The saline reservoir was placed at the level of the transducer without a pressure bag to prevent saline evacuation into the ES, and the zero level was set at the needle insertion point with a laser leveling device (Fig. 1). The Tuohy needle was then advanced, and pressure was recorded continuously. When a sudden drop in the displayed pressure occurred, ES identification was confirmed by the characteristic pulsatile waveform. After identifying the ES, needle insertion depth was measured, and the needle was held immobile for 60 s to stabilize EP. After stabilization, mean airway pressure and mean and peak EP levels were recorded. Then, PIP level was increased from 15 to 25 cmH2O. After stabilization, the ventilator was turned off, reducing airway pressure to zero. Mean airway pressure and mean and peak EP levels were also recorded at a PIP of 25 and 0 cmH2O as described above. After pressure recordings were completed, a 19-gauge multiorifice epidural catheter (Smith Medical MD, St. Paul, MN, USA) was inserted, and the patient was turned to the supine position. Patients were asked immediately after surgery and postoperative 5 days if they had any neurologic symptom.

SPSS software (version 12.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all analyses. EP data were reported as median and interquartile range. Changes in EP at PIPs of 25, 15 and 0 cmH2O were analyzed by paired t-tests with the Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Sample size calculations were based on pilot data (n = 5) showing a pressure difference of 0.9 ± 0.55 mm Hg (mean ± SD) after decreasing airway pressure. Because a minimal sample size of six patients was necessary to demonstrate a significant difference of 1 mmHg with α = 0.05 and β = 0.1, 15 patients were recruited to compensate for possible dropouts.

Epidural analgesic was achieved successfully in 15 patients, with sufficient analgesia during the postoperative period and no neurologic complications.

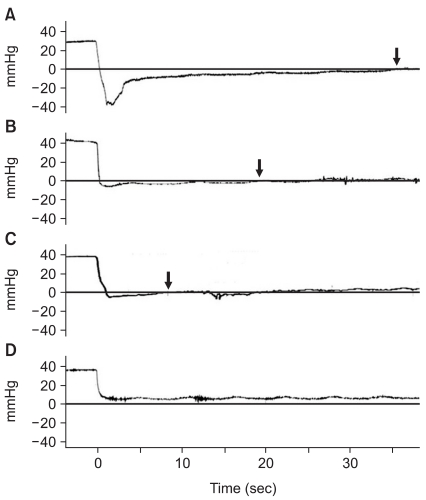

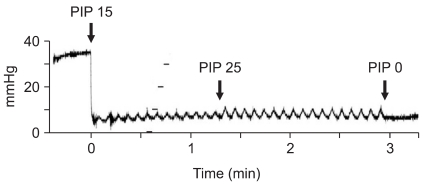

Changes in EP levels during application of positive pressure ventilation are shown in Table 2. EP was increased significantly at 15 cmH2O PIP and further increased at 25 cmH2O PIP (P < 0.001). Median increase in mean and peak EP was 1.5 mmHg (interquartile range, 0.5-1.5) and 2.0 mmHg (1.0-2.0) at 15 cmH2O of PIP, and 1.0 mmHg (1.0-1.5) and 2.0 mmHg (1.0-2.0) at 25 cm H2O of PIP (P < 0.001), respectively. In three cases, an exponential decrease in pressure resulted in initial negative pressures, as previously described by Okutomi et al. [6]. The initial negative EPs were -6, -6, and -40 mmHg, but equilibrated to a positive value in 8, 19, and 35 sec, respectively (Fig. 2). Except for these three cases, all measured lumbar EPs were positive following epidural puncture. In phase with ventilation, EP waves increased with inspiration and decreased with expiration. The range of the ventilatory waveform was 1-2 mmHg at 15 cmH2O of PIP and it increased to 1-4 mmHg at 25 cmH2O of PIP (Fig. 3).

Our results demonstrate the influence of increased airway pressure on lumbar EP measured directly in anesthetized patients undergoing intermittent positive pressure ventilation. EP increased in proportion to the amount of PIP applied. All of the measured lumbar EPs were positive, consistent with previous reports [4,7,8].

The LOR technique is widely used for identification of the ES. However, when performing this technique, one hand is used to grip the epidural needle and the other to test for LOR, resulting in less than optimal stability and control as the needle is advanced. Moreover, LOR relies on detecting a drop in pressure as the needle tip exits the ligamentum flavum. As such, this technique is subjective and operator-dependent and may result in accidental dural puncture. To avoid these issues, several groups have suggested a method to identify the ES using a closed pressure measurement system [9,10]. The characteristic pulsatile pressure tracing transduced through a Tuohy needle allows not only for more sensitive detection of the ES but also for confirmation that the needle is correctly positioned [11,12]. Major benefits of this technique include better needle control, objective pressure end points, and avoidance of false LOR resulting in incorrect catheter depth or position.

Many studies have been conducted about changing waveform of EP. Shah [4] reported that pressure recordings showed large and small types of periodic waves. The large waveform was in phase with positive pressure ventilation, with the pressure increasing during inspiration and decreasing during expiration. The small oscillation waveform was superimposed on a large ventilatory waveform and was synchronous with arterial pulsations. Immediate increase of EP was observed when the jugular vein was compressed and it continued until the compression was released. Iwama and Ohmori [3] reported that the Queckenstedt test and the head-up position to increase or decrease the intracranial pressure also increased or decreased thoracic EP, respectively. In our study, an increase of PIP increased the range of these large waves, and these large waves disappeared when the ventilator was off.

Although direct comparison between studies is challenging and lumbar EP is less affected by airway pressure than is thoracic EP, an earlier study [3] monitored changes in thoracic EP at 0, 5, and 10 cmH2O of PEEP and reported that mean EP increased approximately 5 mmHg for every 5 cmH2O increment of PEEP. Shah [4] also found that lumbar EP increased 1-2 mmHg for every 5 cmH2O of PEEP, but another study [5] examining the effects of continuous positive airway pressure on EP reported equivocal findings. However, these previous studies did not describe the needle zeroing point and monitored EP through the indwelling epidural catheter while patients were supine. Our study directly measured lumbar EP through the Tuohy needle because epidural catheter, when compared with epidural needle, failed to display a sensitive pulsatile pressure waveform, even showing varying results depending on the type of catheter used [12]. We also applied different PIP to change airway pressure because in clinical situations, PEEP is not a routine practice. We showed in this study that EP increased in proportion to the amount of PIP or mean airway pressure applied, but changes in EP were lower than in Shah's study [4].

We observed an initial negative EP in three out of 15 cases. Okutomi et al. [6] previously reported an initial pressure decrease in all patients, resulting in negative EP values in 10 out of 13 patients. EP equilibrated quickly and returned to positive values in 12 patients. They suggested that negative pressure at the moment of epidural puncture was artifactual, resulting from the advancing Tuohy needle producing a bulge of the ligamentum flavum and subsequent adaptation of the surrounding tissue to normalize the pressure. However, Gil et al. [13] observed this initial negative pressure in only two out of 28 cases and suggested that the shape of the epidural needle was the primary factor causing initial negative pressure values. A less curved needle, such as the Tuohy needle used here, will smoothly penetrate the ligamentum flavum without causing the dural tenting or ligamentum flavum retraction that can lead to artifactual negative pressure values. There is still debate whether the pressures reported represent true pressures or artifacts.

Usubiaga et al. [1] recommended thoracic epidural needle insertion during deep spontaneous inspiration due to decreased EP. Another study used epiduroscopy to show that deep inspiration expanded the thoracic ES and collapsed blood vessels [2]. They recommended epidural needle and catheter insertion after maximal inspiration during spontaneous ventilation. However, during positive pressure ventilation, we showed that increasing airway pressure resulted in increased lumbar EP. These results suggest that decreasing airway pressure or turning off the ventilator during epidural needle or catheter insertion may increase success rates and prevent intravascular catheter placement. However, lumbar EP changes due to airway pressure were small compared to thoracic EP changes, and lumbar EP, unlike thoracic EP, was positive. Further studies will help demonstrate the application of our findings to epidural needle and catheter insertion.

A potential criticism of our study is that lumbar epidural catheterization was delivered during general anesthesia. Although epidural catheterization under general anesthesia theoretically increases the risk of undetected nerve injury, it is often necessary in patients who are already intubated, heavily sedated, have painful and unstable fractures, or are in the pediatric age group. Data regarding this risk are limited to individual case reports [14,15]. These include a case of paraplegia after placement of a thoracic epidural catheter in a patient who previously had undergone a lumbar laminectomy, and paraplegia due to intracord catheter placement during attempted thoracic epidural catheterization. However, no new neurologic deficits occurred after placement of cerebrospinal fluid drainage catheters in 530 anesthetized patients and lumbar epidural catheters in 4,298 anesthetized patients [16,17]. Nonetheless, meticulous attention must be paid to epidural catheterization technique, and methods to improve the success of identifying the ES should continue to be optimized.

In conclusion, we report that increasing PIP levels increases lumbar EP measured directly through a Tuohy needle connected to a pressure transducer.

References

1. Usubiaga JE, Moya F, Usubiaga LE. A note on the recording of epidural negative pressure. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1967; 14:119–122. PMID: 6034400.

2. Igarashi T, Hirabayashi Y, Shimizu R, Saitoh K, Fukuda H. The epidural structure changes during deep breathing. Can J Anaesth. 1999; 46:850–855. PMID: 10490153.

3. Iwama H, Ohmori S. Continuous monitoring of lower thoracic epidural pressure. J Crit Care. 2000; 15:60–63. PMID: 10877366.

4. Shah JL. Positive lumbar extradural space pressure. Br J Anaesth. 1994; 73:309–314. PMID: 7946854.

5. Visser WA, Gielen MJ, Giele JL. Continuous positive airway pressure breathing increases the spread of sensory blockade after low-thoracic epidural injection of lidocaine. Anesth Analg. 2006; 102:268–271. PMID: 16368841.

6. Okutomi T, Watanabe S, Goto F. Time course in thoracic epidural pressure measurement. Can J Anaesth. 1993; 40:1044–1048. PMID: 8269565.

7. Telford RJ, Hollway TE. Observations on deliberate dural puncture with a Tuohy needle: pressure measurements. Anaesthesia. 1991; 46:725–727. PMID: 1928670.

8. Thomas PS, Gerson JI, Strong G. Analysis of human epidural pressures. Reg Anesth. 1992; 17:212–215. PMID: 1515387.

9. Ghelber O, Gebhard RE, Vora S, Hagberg CA, Szmuk P. Identification of the epidural space using pressure measurement with the compuflo injection pump--a pilot study. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2008; 33:346–352. PMID: 18675746.

10. Rocco AG, Reisman RM, Lief PA, Ferrante FM. A two-person technique for epidural needle placement and medication infusion. Reg Anesth. 1989; 14:85–87. PMID: 2487669.

11. Ghia Jn, Arora Sk, Castillo M, Mukherji Sk. Confirmation of location of epidural catheters by epidural pressure waveform and computed tomography cathetergram. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2001; 26:337–341. PMID: 11464353.

12. Lennox PH, Umedaly HS, Grant RP, White SA, Fitzmaurice BG, Evans KG. A pulsatile pressure waveform is a sensitive marker for confirming the location of the thoracic epidural space. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2006; 20:659–663. PMID: 17023284.

13. Gil NS, Lee JH, Yoon SZ, Jeon Y, Lim YJ, Bahk JH. Comparison of thoracic epidural pressure in the sitting and lateral decubitus positions. Anesthesiology. 2008; 109:67–71. PMID: 18580174.

14. Bromage PR, Benumof JL. Paraplegia following intracord injection during attempted epidural anesthesia under general anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 1998; 23:104–107. PMID: 9552788.

15. Kao MC, Tsai SK, Tsou MY, Lee HK, Guo WY, Hu JS. Paraplegia after delayed detection of inadvertent spinal cord injury during thoracic epidural catheterization in an anesthetized elderly patient. Anesth Analg. 2004; 99:580–583. PMID: 15271743.

16. Grady RE, Horlocker TT, Brown RD, Maxson PM, Schroeder DR. Mayo Perioperative Outcomes Group. Neurologic complications after placement of cerebrospinal fluid drainage catheters and needles in anesthetized patients: implications for regional anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 1999; 88:388–392. PMID: 9972762.

17. Horlocker TT, Abel MD, Messick JM Jr, Schroeder DR. Small risk of serious neurologic complications related to lumbar epidural catheter placement in anesthetized patients. Anesth Analg. 2003; 96:1547–1552. PMID: 12760972.

Fig. 1

Illustration of a laser leveling device. The zero level of a pressure transducer is set at the insertion point of Tuohy needle.

Fig. 2

Measurement of epidural pressure at 15 cmH2O of peak inspiratory pressure (PIP). Initial negative pressures are observed in 3 patients (A-C). In the other 12 patients, lumbar EPs are positive following epidural puncture (D).

Fig. 3

Measurement of epidural pressure at 15, 25, and 0 cmH2O of peak inspiratory pressure (PIP). The large waveform is in phase with positive pressure ventilation, with the pressure increasing during inspiration and decreasing during expiration. The small oscillation waveform is superimposed on a large ventilatory waveform and is synchronous with arterial pulsations.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download