Abstract

Background

The aim of the present study was to determine the effect-site concentration of remifentanil needed to prevent haemodynamic instability during tracheal intubation with inhaled desflurane induction.

Methods

One hundred American Society of Anesthesiologists I and II female patients were randomized to receive an effect-site concentration of remifentanil of 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 ng/ml. Induction of anaesthesia was started with intravenous injection of propofol 2 mg/kg. Ninety seconds after the completion of propofol injection, rocuronium (0.8 mg/kg) and remifentanil were administered simultaneously with 3% desflurane inhalation. Tracheal intubation was attempted 150 sec after the commencement of remifentanil administration.

Results

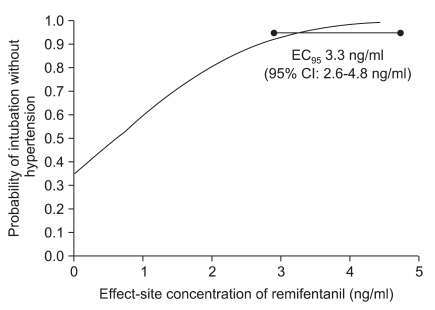

A probit model of remifentanil concentration was predictive of successful intubation without development of hypertension (P for goodness-of-fit = 0.419). The effect-site concentration of remifentanil needed to achieve successful intubation without development of hypertension in 95% of the patients was 3.3 ng/ml (95% confidence interval, 2.6-4.8 ng/ml).

Autonomic responses to laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation might be minimized by a combination of hypnotic and analgesic drugs during induction. Opioids are normally used for analgesia, and hypnosis is usually induced with intravenous anaesthetics such as propofol or thiopental sodium.

With increasing popularity of total intravenous anaesthesia, various studies have reported the optimal dose of remifentanil for reduction of the haemodynamic responses to tracheal intubation with propofol [1-5]. Nevertheless, inhalation anaesthesia is frequently used in clinical practice, but few data have been reported on the optimal dose of remifentanil with inhalation anaesthetics during intubation [6].

This study was designed to determine the effect-site concentration (EC) of remifentanil for preventing development of hypertension during tracheal intubation with inhaled desflurane induction.

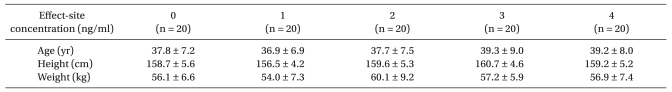

After hospital Ethics Committee approval and patients informed consent, American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status I and II female patients (n = 100) between the age 18 to 60 years who were scheduled for elective surgery were enrolled in this study. The five groups were similar with respect to age, weight, and height (Table 1).

Exclusion criteria included a history of hypertension, cardiac, pulmonary, hepatic, or renal disease. Patients with systolic blood pressure (SBP) higher than 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure higher than 90 mmHg at pre-induction were also excluded.

Heart rate, pulse-oximetry, capnography, and end-tidal desflurane concentration were monitored continuously. Noninvasive blood pressure was measured at a 1-min interval during the study period. Patients were randomly allocated to receive an infusion of remifentanil which was designed to achieve and maintain a predicted target EC of 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 ng/ml. Remifentanil was infused with a target-controlled infusion system (Orchestra®, Fresenius Vial, Brezims, France) using the Minto's model. After preoxygenation, 3 ml of 1% lidocaine was injected to reduce the pain associated with IV administration of propofol. Then, propofol 2 mg/kg was infused. Ninety seconds after the completion of propofol injection and confirmation of loss of consciousness, rocuronium (0.8 mg/kg) and remifentanil were administered simultaneously with 3% desflurane inhalation. Intubation was attempted 150 sec after the commencement of remifentanil administration.

Heart rate and blood pressure were recorded at pre-induction, after the propofol injection, immediately before and after intubation, and at 1 and 2 minutes after intubation. Any incidences of hypotension were recorded. Hypotension was defined as SBP that did not exceed 80 mmHg, or mean arterial blood pressure equal to or less than 55 mmHg. Hypotension was treated with an intravenous bolus of ephedrine 5 mg unless immediate intubation was anticipated. Any incidences of hypertension were also recorded, and this was defined as SBP higher than 120% of the pre-induction baseline values.

Data are presented as mean ± SD or number of patients. In the Cochran-Armitage test for trend in proportions, a sample size of 19 patients per group was required from the five groups with remifentanil dose corresponding to EC of 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 ng/ml, and the proportion of successful intubation without development of hypertension was equal to 0.50, 0.60, 0.70, 0.80, and 0.90 respectively. A total sample size of 95 patients was required to achieve an 86% power to detect a linear trend using a two-sided Z test with continuity correction and a significance level of 0.05 (version 8.0.05, PASS®, NCSS, Kaysville, UT, USA) [7].

SPSS (version 13.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis, and a P value of 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Goodness-of-fit tests were considered to be passed when P value was ≥ 0.05. Patient characteristics between the five groups were compared using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). A probit analysis was used to calculate the EC of remifentanil required to achieve intubation without developing hypertension in 95% of patients. Repeated measures of the haemodynamic value were analyzed using repeated measured analysis of variance with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons when appropriate.

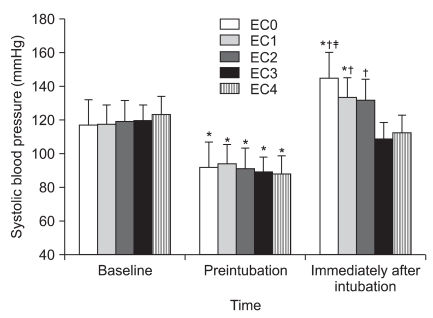

In all the five groups, SBP was significantly decreased prior to intubation, with no significant difference in SBP between the groups (P < 0.001, Fig. 1). Compared to the baseline, SBP was significantly increased by laryngoscopic stimulation in the groups with an EC of remifentanil of 0 or 1 ng/ml (P < 0.05, Fig. 1). After tracheal intubation, SBP was significantly lower in the patient group with an EC of remifentanil of 3 ng/ml than that in the patient groups who had received an EC of remifentanil of 0, 1, or 2 ng/ml (P < 0.05, Fig. 1); whereas, there was no difference in SBP between the groups with an EC of remifentanil of 3 and 4 ng/ml.

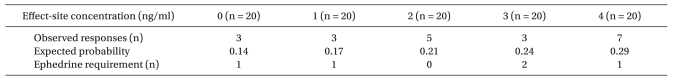

A probit model of remifentanil concentration was predictive of successful intubation without development of hypertension (P for goodness-of-fit = 0.419). An EC of remifentanil needed to achieve successful intubation without development of hypertension in 95% of the patients was 3.3 ng/ml (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.6-4.8 ng/ml, Fig. 2). A probit model with remifentanil concentration for development of hypotension during induction was also predictive (P for goodness-of-fit = 0.648). However, the remifentanil concentration for provoking hypotension in 50 or 90% of the patients could not be estimated because the observed probability was too low (Table 2).

The aim of this study was to determine the optimal EC of remifentanil for achievement of successful intubation without development of hypertension during inhaled desflurane induction.

It has been reported that the EC95 of remifentanil for smooth intubation without muscle relaxants during inhaled desflurane induction is 8.0 ng/ml (95% CI, 5.0-14.3 ng/ml) [6], which is higher than the EC of remifentanil of 3.3 ng/ml needed to achieve successful intubation in 95% of the patients without development of hypertension in the present study. This discrepancy could be due to the differences in study design, such as use of muscle relaxants or due to the different definitions of successful intubations. Even though we used a lower concentration of desflurane compared to that used in the previous study, we think that the muscle relaxant probably reduced the effective remifentanil concentration in this study.

With regards to the drug regimen, we used steady-state infusion of remifentanil during the study period in all the patients, in order to avoid fluctuations in drug concentrations. There have been many studies in which a bolus injection of remifentanil has been used [4,8,9], but this could result in haemodynamic instability. Continuous infusions, and not bolus doses of opiates have been proven to provide a better quality of anesthesia [10].

Hypotension occurred more frequently at a higher remifentanil concentration. However, the incidence of hypotension was estimated to be around 25% with EC95 of remifentanil (3.3 ng/ml), and less than 30% even at the highest remifentanil concentration (EC of 4 ng/ml). We could have used a higher remifentanil concentration if we wanted to use an EC of remifentanil that could provoke hypotension in 50 or 95% of the patients; however, we chose a clinically relevant concentration that could also reveal the possible difference in SBP between the five groups during the transition period between the administration of propofol and the inhaled anaesthetic induction.

Desflurane is an inhalational anaesthetic with a low solubility. Its low solubility allows for rapid induction and emergence from anaesthesia. These favorable pharmacokinetic characteristics are useful in ambulatory surgery because of the shorter post-anaesthetic recovery time. However, neurocirculatory activation with tachycardia and hypertension during rapid increase in the inspired desflurane concentration prevents its widespread use, particularly in the patients with hypertension or ischemic heart disease [11,12].

These unfavorable responses to desflurane have been effectively blunted with a bolus of alfentanil [13] and have been partially reduced with fentanyl [14]. Remifentanil, a derivative of fentanyl, is a rapid onset, ultra-short acting agonist [15], and its rapid kinetics are well matched with those of desflurane. Little is known about the dose of remifentanil that can effectively prevent the haemodynamic response to desflurane inhalation. Weiskopf et al. [16] have reported that maintenance of anaesthesia with 4% desflurane produced no sympathetic or cardiovascular stimulation. To eliminate the possible sympathetic response evoked by desflurane, a 3% inhalation concentration of desflurane was used in this study. There was no difference in the end-tidal concentration of desflurane between the five groups of this study.

In conclusion, the EC of remifentanil for successful intubation without development of hypertension in 95% of patients was 3.3 ng/ml when 2.0 mg/kg of propofol induction was followed by 3% desflurane inhalation. Also, the incidence of hypotension was estimated to be approximately 25% following this drug regimen.

References

1. Kang TU, Shin HC, Lim HS, Ko SH, Han YJ, Kim DC. Optimal dosages of propofol and remifentanil for minimizing hemodynamic changes during laryngeal microscopic surgery. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2008; 55:314–319.

2. Kim SJ, Yoo KY, Park BY, Kim WM, Jeong CW. Comparison of intubating conditions and hemodynamic responses to tracheal intubation with different effect-site concentrations of remifentanil without muscle relaxants during target-controlled infusion of propofol. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2009; 57:13–19.

3. Ithnin F, Lim Y, Shah M, Shen L, Sia AT. Tracheal intubating conditions using propofol and remifentanil target-controlled infusion: a comparison of remifentanil EC50 for Glidescope and Macintosh. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2009; 26:223–228. PMID: 19237984.

4. Bouvet L, Stoian A, Rimmelé T, Allaouchiche B, Chassard D, Boselli E. Optimal remifentanil dosage for providing excellent intubating conditions when co-administered with a single standard dose of propofol. Anaesthesia. 2009; 64:719–726. PMID: 19624626.

5. Troy AM, Huthinson RC, Easy WR, Kenney GN. Tracheal intubating conditions using propofol and remifentanil target-controlled infusions. Anaesthesia. 2002; 57:1204–1207. PMID: 12479190.

6. In J, Shin HI, Chung SH, Kim KO, Choi JG, Lee Y, et al. Effect-site concentration of remifentanil for smooth tracheal intubation without muscle relaxants provokes hypotension under desflurane anesthesia. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2008; 55:31–35.

7. Nam JM. A simple approximation for calculating sample sizes for detecting linear trend in proportions. Biometrics. 1987; 43:701–705. PMID: 3663825.

8. Iannuzzi E, Iannuzzi M, Cirillo V, Viola G, Parisi R, Cerulli A, et al. Peri-intubation cardiovascular response during low dose remifentanil or sufentanil administration in association with propofol TCI. A double blind comparison. Minerva Anestesiol. 2004; 70:109–115. PMID: 14997083.

9. Alexander R, Olufolabi AJ, Booth J, El-Moalem HE, Glass PS. Dosing study of remifentanil and propofol for tracheal intubation without the use of muscle relaxants. Anaesthesia. 1999; 54:1037–1040. PMID: 10540091.

10. White PF. Clinical uses of intravenous anesthetic and analgesic infusions. Anesth Analg. 1989; 68:161–171. PMID: 2643889.

11. Weiskopf RB, Eger EI 2nd, Noorani M, Daniel M. Repetitive rapid increases in desflurane concentration blunt transient cardiovascular stimulation in humans. Anesthesiology. 1994; 81:843–849. PMID: 7943835.

12. Muzi M, Lopatka CW, Ebert TJ. Desflurane-mediated neurocirculatory activation in humans. Effects of concentration and rate of change on responses. Anesthesiology. 1996; 84:1035–1042. PMID: 8623996.

13. Yonker-Sell AE, Muzi M, Hope WG, Ebert TJ. Alfentanil modifies the neurocirculatory responses to desflurane. Anesth Analg. 1996; 82:162–166. PMID: 8712395.

14. Pacentine GG, Muzi M, Ebert TJ. Effects of fentanyl on sympathetic activation associated with the administration of desflurane. Anesthesiology. 1995; 82:823–831. PMID: 7717552.

15. Scott LJ, Perry CM. Remifentanil: a review of its use during the induction and maintenance of general anaesthesia. Drugs. 2005; 65:1793–1823. PMID: 16114980.

16. Weiskopf RB, Moore MA, Eger EI 2nd, Noorani M, McKay L, Chortkoff B, et al. Rapid increase in desflurane concentration is associated with greater transient cardiovascular stimulation than with rapid increase in isoflurane concentration in humans. Anesthesiology. 1994; 80:1035–1045. PMID: 8017643.

Fig. 1

Systolic blood pressure (SBP) changes in the five groups. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval. In all the five groups of patients, SBP was significantly decreased prior to intubation, with no significant difference in SBP between the five groups. SBP was significantly increased after tracheal intubation compared to the baseline value in the groups EC0 and EC1. SBP after tracheal intubation was significantly lower in group EC3 than SBP in the groups EC0, 1 and 2 (P < 0.05). SBP after tracheal intubation was significantly lower in group EC4 than that in group EC0. EC0: remifentanil 0 ng/ml, EC1: remifentanil 1 ng/ml, EC2: remifentanil 2 ng/ml, EC3: remifentanil 3 ng/ml, EC4: remifentanil 4 ng/ml, *P < 0.05 compared with baseline values. †P < 0.05 compared with group EC3. ‡P < 0.05 compared with group EC4.

Fig. 2

Effect-site concentration and response curve of remifentanil from the probit analysis. The effect-site concentration of remifentanil for successful intubation without development of hypertension in 95% of the patients was 3.3 ng/ml (95% CI: 2.6-4.8 ng/ml). EC: effect-site concentration.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download