Abstract

Background

Subarachnoid block is widely used for cesarean section due to the rapid induction, the complete analgesia, the low failure rate and the prevention of aspiration pneumonia. The addition of intrathecal opioids to local anesthetics seems to improve the quality of analgesia & prolong the duration of analgesia. Therefore we compared the effects of fentanyl 20 µg and sufentanil 2.5 µg, which were added to intrathecal hyperbaric bupivacaine.

Methods

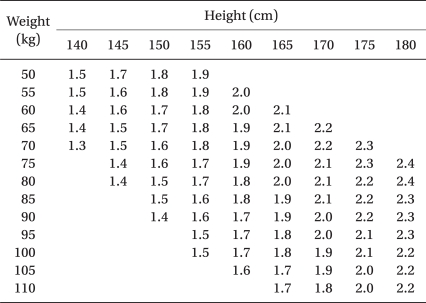

Seventy two healthy term parturients were randomly divided into three groups: Group C (control), Group F (fentanyl 20 µg) and Group S (sufentanil 2.5 µg). In every group, 0.5% heavy bupivacaine was added according to the adjusted dose regimen by Harten et al. We observed the maximal level of the sensory block and motor block, the quality of intraoperative analgesia, the duration of effective analgesia and the side effects.

Results

There were significant differences between the control and the fentanyl 20 µg and sufentanil 2.5 µg groups for the degree of muscle relaxation, the quality of intraoperative analgesia, the maximal sedation level and the duration of effective analgesia. The frequencies of side effects such as nausea and pruritis in the opioid groups were higher than those in the control group. But there were no differences between fentanyl 20 µg and sufentanil 2.5 µg for the frequencies of nausea and pruritis.

There are two general types of regional anesthesia for cesarean section and these are the spinal and epidural techniques. Both these techniques are commonly used to reduce the complications associated with general anesthesia such as pneumonia, post-operative pain, etc. Spinal anesthesia is simpler to place and it works fast enough to obtain effective sensory and motor block and so its use is increasing.

Hyperbaric 0.5% bupivacaine is often used for spinal anesthesia, and this drug is well-known to reduce visceral pain more effectively than tetracaine, which was commonly used before bupivacaine became available. However, sometimes bupivacaine may fail to prevent visceralgia and the induced pain during traction of the peritoneum [1]. To compensate for this shortcoming, the addition of a small portion of opioid to the local anesthetics is widely used clinically as a more effective method to improve the quality of intra-operative anesthesia and control the post-operative pain [2].

Morphine as an aqueous opioid is the most studied among the opioids and it has an advantage of being a long-acting analgesia, but its onset time is slow and there exists side-effects such as nausea, vomiting and respiratory depression [3,4], and this has encouraged research on other opioids. On the other hand, fentanyl or sufentanil as a liposoluble opioid is known to have less such side-effects and to be effective for maintaining the proper depth of anesthesia and controlling the post-operative pain [5].

Even though there are many research reports on the effects of individual opioids or that have compared morphine and other liposoluble opioids, there are only rare studies that have compared between liposoluble opioids. We compared the clinical effects of adding fentanyl 20 µg or sufentanil 2.5 µg to hyperbaric bupivacaine to that of the control group that was without any opioid additives.

The present study was approved by our Institutional Bioethics Board for clinical research and the study population consisted of seventy two full-term parturients with an American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status of I-II and they were scheduled to undergo elective cesarean section and they consented to receive spinal anesthesia. The parturients who had contraindications to spinal anesthesia or a high risk of gestational hypertension, diabetes and/or placenta previa were excluded.

The seventy two parturients were randomly divided into three groups of 24 persons each: Group C (the control group without any opioid additives), Group F (with the addition of fentanyl 20 µg) and Group S (with the addition of sufentanil 2.5 µg). These groups were based on the adjusted dose regimen for hyperbaric bupivacaine 0.5%, with giving consideration to the patients' heights and weights when it was used as spinal anesthesia for cesarean section as in Harten et al.'s report [6].

All the subjects did not receive any premedication and at their arrival into the operating room (OR) they were intravenously injected with 10 ml/kg Ringer's lactate solution via an 18-G venous catheter until the induction of anesthesia. The electrocardiogram (EKG), a non-invasive auto-blood pressure (BP) measurement instrument and pulse oximetry were set up for monitoring the vital signs, while oxygen was provided at 5 L/min using face mask ventilation until the end of the operation.

To perform spinal anesthesia, the patients were placed into a right lateral decubitus position and after the needle insertion site was disinfected, a dural puncture was made with a 26-G Whitacre spinal needle at the L3-L4 or L2-L3 lumbar vertebrae space. The location of the subarachnoid space was then confirmed by the leakage and aspiration of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Each hyperbaric solution of bupivacaine (Table 1) was slowly injected to the patients of each group for approximately 30 seconds: there was no addition of opioid for Group C, fentanyl 20 µg was added for Group F and sufentanil 2.5 µg was added for Group S.

From the end of injecting the local anesthetics, the patients' BP and pulse were measured at 2 minute intervals during the first 20 minutes and thereafter at 5 minute intervals until the end of the operation. A systolic BP under 90 mmHg or a BP decreased to 20% of the first measured BP was defined as hypotension, and ephedrine 4-8 mg was promptly intravenously infused. We recorded the side-effects that the patients complained of such as nausea, vomiting, pruritus and/or chills. The sensory block division levels were evaluated by pinprick tests that were done at 2 minute intervals after the induction of anesthesia, while the level of motor blockade was assessed using the Modified Bromage scale. That is, movements are recorded on a four-point scale: 0 = able to raise an extended leg was no motor block; 1 = unable to raise an extended leg, but able to flex the knee; 2 = unable to flex the knee, but with free movement of the ankle; 3 = unable to flex the ankle. The peak sensory block level, the degree of motor blockade, the sensory block levels and the Bromage scale 120 minutes after the induction of anesthesia were also measured.

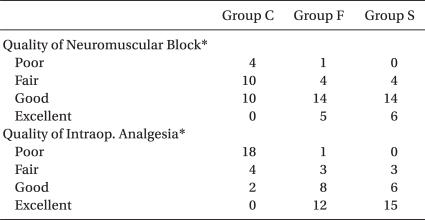

The operation began only when the sensory block level was T6 or above. The degrees of muscle relaxation during the operation, which the surgeons rated, were classified into 4 grades: 1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good and 4 = excellent. The intra-operative analgesic effects were estimated as 4 grades: excellent = the patient felt comfortable during operation, no complaints; good = a little discomfort but no need for additive medication; fair = discomfort, but controlled by additive medication such as fentanyl, propofol, dormicum, etc.; poor = unable to be controlled even with additive medication.

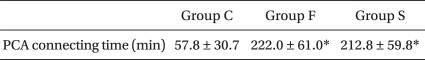

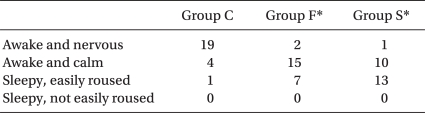

The degree of intra-operative sedation of the parturients was described as 1 = awake and nervous, 2 = awake and calm, 3 = sleepy but easily aroused and 4 = sleepy and not easily aroused. The surgical team was previously informed to connect the patient controlled analgesia (PCA) at the time when the patients needed analgesics due to post-operative pain. The effective analgesic duration was indirectly evaluated by recording the interval time from the time point of completion of infusing the local anesthetics to that of connecting the patient to the PCA. The Apgar scores were recorded at 1 and 5 minutes after birth to assess the health of the newborn infants.

For statistical comparison between the three groups, Chisquare tests and Fischer's exact tests were used for the maximum Bromage scale (hereafter referred to as the max. B/S), the Bromage scale at 120 minutes after the induction of anesthesia (hereafter hereafter referred to as the B/S 120 min), the side-effects (hypotension, nausea, vomiting, pruritus and/or chills), degree of muscle relaxation, the intra-operative analgesic effects and the sedation conditions. One-way ANOVA was used for the other observed results, and statistically significant differences were confirmed by Turkey test among the multiple comparison methods. For all of the statistical processes, P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

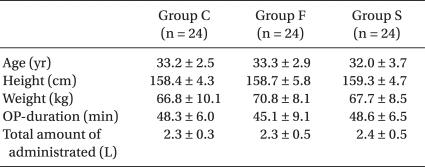

There were no differences between the three groups for age, height, weight and the operation time, while the mean volumes of bupivacaine used for Group C, Group F and Group S were 9.3 ± 0.7, 9.3 ± 0.8 and 9.4 ± 0.5 mg, respectively, and there were no statistically significant differences. In addition, the infused amount of intravenous (IV) fluid, the frequency of hypotension and the dosage of ephedrine did not reveal any significant differences (Table 2).

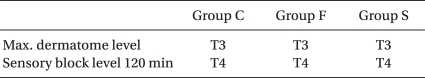

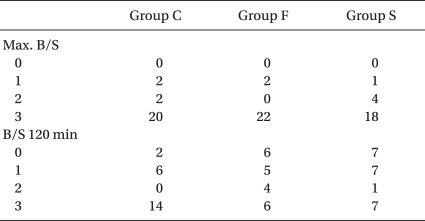

A peak sensory block height of > T4 was attained in each group, and there were no significant differences between the three groups (Table 3). The sensory block height at 120 minutes after the induction of anesthesia, the max. B/S and the B/S 120 min did not show any significant differences between each group (Table 4).

As for the degree of muscle relaxation, the number of the patients who were assessed as 'good' or above in Group C, Group F, and Group S was 10, 19 and 20, respectively, and which Group F and Group S reached a high level and this showed statistical significance as compared with that of Group C. For the intra-operative analgesic effects, the number of the patients who were evaluated as 'good' or above was 2, 20 and 21 for Group C, Group F and Group S, respectively, and Group F and Group S showed excellent results (Table 5).

The duration of effective analgesia, as indirectly measured by the PCA connecting time, showed significance differences between Group C and both Group F and Group G, whereas there was no significant difference between Group F and Group G (Table 6).

For the degree of intra-operative sedation of the parturients, the majority of the Group C patient were awake and nervous, whereas the number of parturients who were awake in a comfortable condition or drowsy, but easily arousable was 22 and 23 for Group F and Group G, respectively, which indicated a statistic difference from the control group (Table 7).

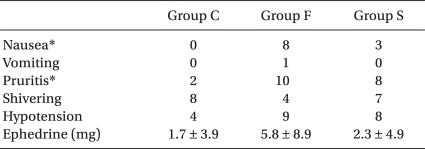

Among the complications, the incidence of nausea and pruritus was significantly increased in Group F and Group S rather than in Group C, while other complications did not show any significant difference between the groups (Table 8).

The Apgar scores measured at 1 minute and 5 minutes after birth were 8-9, and there were no differences between the three groups.

There are two general categories of anesthesia for cesarean section: general anesthesia and regional anesthesia. Due to its efficacy to reduce the risks of aspiration pneumonia and fetal suppression induced by the systemic administration of anesthetics, regional anesthesia is now much preferred to general anesthesia. Spinal block is more commonly used in clinical practice than epidural block out of the regional anesthesia techniques because spinal anesthesia is less technically complicated, it is faster to induce anesthesia, it works well for intra-operative analgesia, it excels for muscle relaxation and it uses a small dosage of local anesthetics. However, spinal block also has disadvantages such as the incidences of hypotension and post-dural puncture headache (PDPH), the difficulty in controlling the height of anesthesia, etc. [7-9].

For spinal anesthesia, it is known that the use of a single local anesthetic may be incomplete for blocking the intra-operative pain, the patient is vulnerable to visceralgia during traction of the peritoneum and there is more difficultly for controlling the post-operative pain than when using epidural anesthesia [1]. Although an attempt to raise the block height by increasing the volume of local anesthetics was tried in an effort to resolve such problems, this turned out not to be a complete solution when considering such reports that there exists risks of blocking the cervical spinal nerves and total spinal block [7] and that the use of bupivacaine 15 mg caused intra-operative pain. Several research papers have argued that the addition of various opioids to local anesthetic showed improved the intra-and-post operative analgesic effects [2,5,10-12], which is attributed to the block of the olfactory sensation of the spinal tract when administering opioid into the subarachnoid space [13].

Morphine is the most studied (aqueous) opioid, and it is characterized by a slow onset time because it is so ionized in the subarachnoid space that it is slowly absorbed into the opioid receptors of the spinal cord, and morphine has a long period of action because it remains at a high density in the subarachnoid space, while there exists the possibility that prolonged hypoventilation may be induced by the rostral spread of administered morphine [3,4]. On the other hand, fentanyl and sufentanil, which are both liposoluble opioids, have a faster onset time and a shorter period of action because they rapidly interact with the opioid receptors of the spinal cord, and they have a low risk of hypoventilation due to their limited rostral spread [5].

There are different opinions about the proper dosage of bupivacaine used in the spinal anesthesia for Cesarean section, but a recent study suggested that the addition of fentanyl 0.15 µg/kg or meperidine 0.25-5.0 mg/kg to a mixture requires only 9 mg of hyperbaric 0.5% bupivacaine to attain a proper height of anesthesia [14] and that the addition of fentanyl 10 µg to 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine 8 mg is able to maintain a proper height of anesthesia [15]. Harten et al. [6] reported that comparison between a fixed dosage regimen of local anesthetics and a dosage regimen of local anesthetics adjusted to the patient's height and weight revealed that the adjusted dosage regimen reduces the incidence of hypotension, it reduces the administered dose of ephedrine and the blocked height levels and it maintains a proper height of anesthesia.

In this regard, the present study decided on the dosage of local anesthetics by referring to the table of the adjusted dose regimen for hyperbaric 0.5% bupivacaine suggested by Harten et al. [6] (Table 1).

Studies that have compared the maximal block levels when sufentanil was added at spinal anesthesia for Cesarean section [16,17] as well as Dahlgren et al.'s research [2] supported that block up to T4 is the adequate anesthesia height during operation. The present study also found that the maximal block level reached the proper block height of T4 or above, which is enough for the operation, and there was no incidence of excessively high block.

Among the studies on the effects of opioid additives on intra-operative analgesia, Chu et al. [16] reported that the addition of fentanyl 12.5 µg or 15 µg to hyperbaric 0.5% bupivacaine 15 mg significantly reduced the intra-operative pain as compared with the control group, while Hunt et al. [17] showed that the groups administered additional fentanyl 0.25, 0.5 and 0.75 µg/kg complained of no intra-operative pain. In the present study, 22 out of 24 patients in the Control Group needed additional drugs and they showed unsatisfactory analgesic effects, whereas 21 in the fentanyl 20 µg Group and 21 in the sufentanil 2.5 µg Group did not require additional drugs and they showed satisfactory analgesic effects during operation.

The duration of effective analgesia is improved by the addition of sufentanil 5.0 and 7.5 µg according to Braga Ade et al. [18] and it is effectively prolonged by the addition of sufentanil 1.5, 2.5 and 5.0 µg. Comparison of fentanyl and sufentanil [2] demonstrated that the duration of effective analgesia was significantly increased in the sufentanil 2.5 and 5.0 µg groups in contrast with that of the control group and the fentanyl 10 µg group. In the present study, the groups that were administered fentanyl 20 µg and sufentanil 2.5 µg showed a significantly increased duration of effective analgesia, as compared with that of the control group, while there was no difference between the fentanyl 20 µg and sufentanil 2.5 µg groups.

In the present study, vomiting and chills did not show any significant differences between the three groups, while the incidences of nausea and pruritus were increased more significantly in the opioid-added groups than in the control group, which indicates results similar to the previous research. Studies by Braga Ade et al. [18] and Demiraran et al. [19] revealed that the incidence of pruritus increases as the dose of the added sufentanil increases. In a previous study, the incidence of pruritus with the administration of opioid into the subarachnoid space was 62% for morphine, 67% for fentanyl and 80% for sufentanil [20]. Although the mechanisms of neuraxial opioid-induced pruritus remain unclear, it is postulated that not only the activation of an itch center in the central nervous system (CNS) and the medullary dorsal horn, but also the antagonism of inhibitor transmitters are involved [21]. The treatment for opioid-induced pruritus includes antihistamines, opiate-antagonists, propofol, NSAIDS, 5-HT3 receptor antagonist (Ondansetron), etc., among which propofol and Ondansetron are commonly used [21,22].

The fact that the Apgar scores of the newborn babies were not significantly different between the groups and that the Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes shows high scores of 8 or 9 seem to suggest that opioid administered into the subarachnoid space does not suppress newborn infants, which is consistent with the previously mentioned studies.

In conclusion, the groups with fentanyl 20 µg and sufentanil 2.5 µg added to hyperbaric 0.5% bupivacaine showed good muscle relaxation and enough intraoperative analgesia for a Caesarian operation, and they had a prolonged duration of effective analgesia, compared with that of the control group. Considering that the groups that received fentanyl 20 µg and sufentanil 2.5 µg showed a significant increased incidence of nausea and pruritus, further dose-dependent studies are required to determine the optimal doses of fentanyl and sufentanil.

References

1. Pedersen H, Santos AC, Steinberg ES, Schapiro HM, Harmon TW, Finster M. Incidence of visceral pain during cesarean section: the effect of varying doses of spinal bupivacaine. Anesth Analg. 1989; 69:46–49. PMID: 2742167.

2. Dahlgren G, Hultstrand C, Jakobsson J, Norman M, Eriksson EW, Martin H. Intrathecal sufentanil, fentanyl, or placebo added to bupivacaine for cesarean section. Anesth Analg. 1997; 85:1288–1293. PMID: 9390596.

3. Ummenhofer WC, Arends RH, Shen DD, Bernards CM. Comparative spinal distribution and clearance kinetics of intrathecally administered morphine, fentanyl, alfentanil, and sufentanil. Anesthesiology. 2000; 92:739–753. PMID: 10719953.

4. Abouleish E, Rawal N, Fallon K, Hernandez D. Combined intrathecal morphine and bupivacaine for cesarean section. Anesth Analg. 1988; 67:370–374. PMID: 3354872.

5. Belzarena SD. Clinical effects of intrathecally administered fentanyl in patients undergoing cesarean section. Anesth Analg. 1992; 74:653–657. PMID: 1567031.

6. Harten JM, Boyne I, Hannah P, Varveris D, Brown A. Effects of a height and weight adjusted dose of local anaesthetic for spinal anaesthesia for elective Caesarean section. Anaesthesia. 2005; 60:348–353. PMID: 15766337.

7. Finucane BT. Spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery. The dosage dilemma. Reg Anesth. 1995; 20:87–89. PMID: 7605769.

8. Irestedt L. Spinal anaesthesia for caesarean delivery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand Suppl. 1998; 113:21–23. PMID: 9932115.

9. Riley ET, Cohen SE, Macario A, Desai JB, Ratner EF. Spinal versus epidural anesthesia for cesarean section: a comparison of time efficiency, costs, charges, and complications. Anesth Analg. 1995; 80:709–712. PMID: 7893022.

10. Choi DH, Ahn HJ, Kim MH. Bupivacaine-sparing effect of fentanyl in spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2000; 25:240–245. PMID: 10834777.

11. Thi TV, Orliaguet G, Liu N, Delaunay L, Bonnet F. A dose-range study of intrathecal meperidine combined with bupivacaine. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1992; 36:516–518. PMID: 1514334.

12. Abboud TK, Dror A, Mosaad P, Zhu J, Mantilla M, Swart F, et al. Mini-dose intrathecal morphine for the relief of post-cesarean section pain: safety, efficacy, and ventilatory responses to carbon dioxide. Anesth Analg. 1988; 67:137–143. PMID: 3277478.

13. Fields HL, Emson PC, Leigh BK, Gilbert RF, Iversen LL. Multiple opiate receptor sites on primary afferent fibres. Nature. 1980; 284:351–353. PMID: 6244504.

14. Choi JH, Kong MH, Lim SH, Lee MK. Comparison of intrathecal meperidine, fentanyl, or placebo added to 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine for Cesarean section. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2000; 38:49–57.

15. Choi DH, Kang YJ, Chung IS. Spinal anesthesia for Cesarean section: a comparison of three doses of hyperbaric bupivacaine mixed with fentanyl. Korean J Anesthesiol. 1998; 35:88–93.

16. Chu CC, Shu SS, Lin SM, Chu NW, Leu YK, Tsai SK, et al. The effect of intrathecal bupivacaine with combined fentanyl in cesarean section. Acta Anaesthesiol Sin. 1995; 33:149–154. PMID: 7493145.

17. Hunt CO, Naulty JS, Bader AM, Hauch MA, Vartikar JV, Datta S, et al. Perioperative analgesia with subarachnoid fentanyl-bupivacaine for cesarean delivery. Anesthesiology. 1989; 71:535–540. PMID: 2679237.

18. Braga Ade F, Braga FS, Potério GM, Pereira RI, Reis E, Cremonesi E. Sufentanil added to hyperbaric bupivacaine for subarachnoid block in Caesarean section. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2003; 20:631–635. PMID: 12932064.

19. Demiraran Y, Ozdemir I, Kocaman B, Yucel O. Intrathecal sufentanil (1.5 microg) added to hyperbaric bupivacaine (0.5%) for elective cesarean section provides adequate analgesia without need for pruritus therapy. J Anesth. 2006; 20:274–278. PMID: 17072691.

20. Kjellberg F, Tramèr MR. Pharmacological control of opioid-induced pruritus: a quantitative systematic review of randomized trials. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2001; 18:346–357. PMID: 11412287.

21. Szarvas S, Harmon D, Murphy D. Neuraxial opioid-induced pruritus: a review. J Clin Anesth. 2003; 15:234–239. PMID: 12770663.

22. Park CH, Jung HJ. Treatment of epidural-morphine induced pruritus: propofol versus naloxone. J Korean Pain Soc. 1997; 10:208–213.

Table 1

The Adjusted Dose Regimen for Hyperbaric Bupivacaine 0.5% When Used for Spinal Anesthesia for Cesarean Section (ml) [6]

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download