Abstract

The occurrences of pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax after oral and/or maxillofacial surgery are rare, but both are potentially life-threatening complications. Most of the cases that present pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax in the oral and/or maxillofacial surgery result from air dissecting down the fascial planes of the neck. We report a case of a 23-year-old male patient who underwent bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomy under general anesthesia and developed pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax without any traumatic introduction of air through the cervical fascia three days postoperatively. The possible causes and its prevention are discussed with a review of the relevant literature.

Go to :

Pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax are rare complications that occur after oral and/or maxillofacial surgery. The mechanisms for introduction of air into the mediastinal or pleural spaces are by traumatic disruption of the chest wall or cervical fascia, and by alveolar rupture due to increased intra-alveolar pressure [1]. Pneumomediastinum that occurs after oral and/or maxillofacial surgery is reportedly the result of air usually dissecting along the fascial planes of the neck [2]. Pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax occurring from increased intra-alveolar pressure and alveolar rupture are very rare after oral and/or maxillofacial surgery. Patients who have intermaxillary fixation for bone union can experience difficulty with oral breathing after orthognathic surgery. Also, edema from damage or irritation to the nasal mucous membrane in nasotracheal intubation may trigger respiratory difficulty in many patients. So, even if a patient complains of respiratory difficulty after surgery, pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax may not be naturally suspected [3].

The present report describes a patient who underwent an uneventful maxillofacial surgery, but who 3 days later complained of respiratory difficulty and experienced bronchus obstruction from secretion and mucous, atelectasis, pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax induced by alveolar rupture from an increase in intra-alveolar pressure.

A 23-year-old male patient 167 cm in height and 62 kg in weight with a malocclusion was admitted for bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomy and genioplasty. The physical examination and laboratory findings including chest X-ray taken before the surgery were normal.

As premedication, glycopyrrolate 0.2 mg was administered intramuscularly (IM) 20 minutes prior to induction of anesthesia. Fentanyl 0.1 mg, 2% lidocaine 40 mg, propofol 120 mg, and succinylcholine 70 mg were administered intravenously (IV). After adequate muscle relaxation, naso-tracheal intubation was performed without difficulty. Immediately afterwards, manual ventilation was performed. Auscultation of both lungs was unremarkable. Volume-control ventilation was maintained with a tidal volume and respiratory rate of 500 ml and 10-13/min, respectively. The airway pressure was maintained at 15-18 cmH2O, and the end-tidal carbon dioxide was 34-37 mmHg. For maintenance of anesthesia, oxygen 1.5 L/min, nitrous oxide 1.5 L/min, desflurane 6-7 vol% were administered. For muscle relaxation, vecuronium 0.1 mg/kg was administered IV and was repeated while observing the patient's level of muscle relaxation.

The patient's vital signs were stable during the surgery. At the end of the surgery, intermaxillary fixation was performed. With the return of spontaneous breathing, assisted respiration was performed. Glycopyrrolate 0.4 mg and pyridostigmine 15 mg were administered IV to reverse muscle relaxation. After confirming proper spontaneous breathing, the patient was moved to the recovery room. After recovering consciousness, the patient was extubated, and nasopharyngeal suction was performed numerous times. In the recovery room, the patient's vital signs were stable, prompting relocation to the ward.

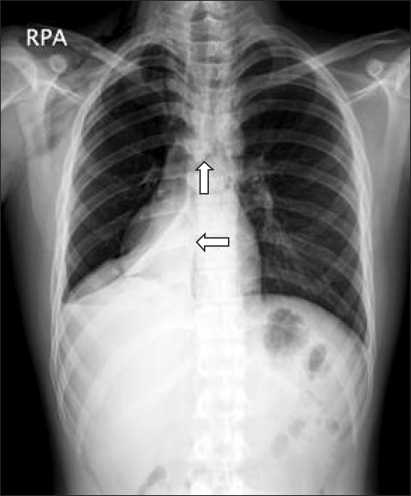

The chest X-ray taken 1 hour after the surgery was normal. On the day of the surgery, the patient presented a lot of sputum and complained of slight respiratory difficulty. Oxygen saturation on the pulse oximetry was 99%. The patient complained of the same symptoms even on the first 2 days after the surgery, but vital signs were the same. On post-op day 3, the patient complained of severe respiratory difficulty and the right chest pain. The patient was supplied with oxygen (O2) at a rate of 6 L/min by nasal cannula, and oxygen saturation on the pulse oximetry was 81-94%. The chest X-ray showed pneumomediastinum, subcutaneous emphysema of the right neck and chest, right pneumothorax, and right lower lobe atelectasis (Fig. 1). The electrocardiogram revealed sinus bradycardia. Creatine kinase (CK), troponin I, D-dimer, and CK-MB levels in the blood were normal.

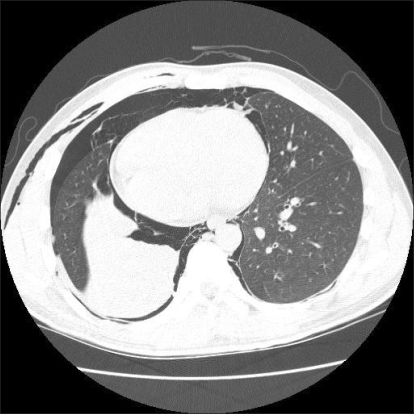

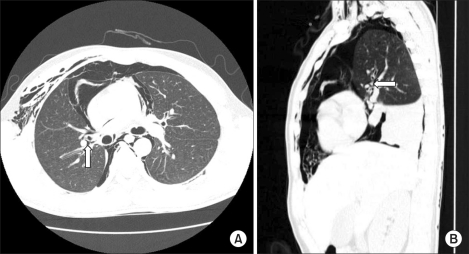

On post-op day 4, the patient's respiratory difficulty and chest pain worsened. A chest computed tomography (CT) discovered subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastinum with right pulmonary interstitial emphysema, right pneumothorax, and right middle and lower lobe atelectasis due to the retention of secretion or mucoid impaction in the right middle and lower lobar bronchus (Fig. 2), right upper lobe parenchyma tearing, and bronchus dissection (Fig. 3A and 3B). Chest tube insertion and skin incision above the sternum were performed to release air by chest surgery, after which the patient's respiration was improved. After chest tube insertion, the patient was administered O2 6 L/min by nasal cannula. The arterial blood gas analysis showed pH 7.45, PCO2 35 mmHg, PO2 132 mmHg, and HCO3 25 mmol/L. The chest X-ray still showed the presence of right lower lobe atelectasis, but the right pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax was reduced. Afterwards, the patient no longer complained of respiratory difficulty. From post-op day 5, a chest X-ray was taken every day, which showed the gradual reduction of the right pneumothorax. A chest CT taken on post-op day 7 showed reductions of the pneumomediastinum, right pneumothorax, subcutaneous emphysema, right interstitial emphysema, and the right middle and lower lobe atelectasis. On post-op day 9, no air was released through the chest tube, so it was removed. The patient was discharged on post-op day 14.

Go to :

Pneumomediastinum is defined as air presence in the mediastinum. It can be subclassified as spontaneous pneumomediastinum of no clear cause and secondary pneumomediastinum accompanying trauma, intrathoracic infection, and damage in the aerodigestive track [4]. Secondary pneumomediastinum might occur from chest damage, esophageal rupture, Boerhaave's syndrome, perforation of tracheobronchial tree, pulmonic abscess rupture, gas-forming intra-thoracic infection, and carcinoma of the lung [5,6]. Secondary pneumomediastinum reportedly occurs after esophageal perforation during an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy [7], dental extraction [8], mandible fracture [9], and oral and maxillofacial surgery [2,10].

There are two explanations for the mechanism of the occurrence of pneumomediastinum after oral and/or maxillofacial surgery. The first is introduction of air from trauma of the chest wall or cervical fascia. The second is introduction of air into the mediastinum and pleural cavity from alveolar rupture by increased intra-alveolar pressure, which is induced by choking, coughing, and mucous plugging in dental patients, or by vigorous ventilatory support with mechanical ventilation and an ambu bag [1,2].

The mechanism of pneumomediastinum from alveolar rupture might be explained by the Macklin effect [11,12]. The Macklin effect is the term of pathophysiologic process of introduction of air into the mediastinum through perforation of the pulmonary interstitium by alveolar rupture. When the intra-alveolar air pressure increases rapidly, air released from the ruptured alveoli causes pulmonary interstitial emphysema, dissects along the bronchovascular sheath to the mediastinum, and causes pneumomediastinum. The intra-alveolar pressure elevation can be caused not only by chest trauma, but also by coughing, asthma, and positive-pressure mechanical ventilation, Valsalva maneuvers, hiking, riding an airplane, diving, and other circumstances where the sudden pressure change causes the elevation of the intra-alveolar pressure [4,11-15]. The Macklin effect can be indirectly confirmed when abnormal linear air forms near the pulmonary vessels and bronchus is observed in the chest CT [12,14], as in the present case.

The preoperative chest X-ray of the patient did not show pneumomediastinum or pneumothorax. Neither was there damage of the chest wall or cervical fascia, which was found in other reported cases of pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax after maxillofacial surgery. We did not perform excessive mechanical ventilation to the point that would cause pressure damage during the surgery. Neither did we perform excessive positive pressure ventilation or assisted mechanical ventilation during and after the surgery. Also, the patient did not experience excessive coughing in the recovery room or in the ward. Therefore, the occurrence of the pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax in the presented case is considered to have started from the intermaxillary fixation placed in the oral cavity, which caused difficulty in deep breathing and adequate coughing. The improper removal of the hemorrhage and the secretion in the oral cavity is assumed to have led to the retention of secretion causing right middle and lower lobar bronchus obstruction and atelectasis. Also, excessive pressure in the right upper lobe despite normal respiratory tidal volume is believed to have triggered the right upper lobe parenchyma tearing and bronchus dissection, leading to pneumomediastinum and right pneumothorax. Chest CT findings of atelectasis from the retention of the secretion or mucuoid impaction in the right middle-lower lobar bronchus, right upper lobe parenchyma tearing, bronchus dissection, and pneumomediastinum and right pneumothorax with right pulmonary interstitial emphysema support our assumptions.

When pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax occur after surgery, patients can complain of respiratory difficulty and chest pain. Depending on their progress, respiratory failure and circulatory disturbance can occur, so early diagnosis and treatment are necessary [1,3]. Patients who have intermaxillary fixation for bone union after orthognathic surgery have difficulty with oral breathing. Many patients complain of respiratory difficulty caused from edema due to damage or irritation to the nasal mucous membrane in naso-tracheal intubation [3]. Therefore, it is not easy to suspect pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax from respiratory difficulty after the uneventful oral and/or maxillofacial surgery. In the present case, the respiratory difficulty was not apparent as abnormal chest X-ray findings. Also, oxygen saturation on the pulse oximetry was in the normal range, so no measures were taken to improve the respiratory difficulty.

In surgeries such as orthognathic surgery that require nasotracheal intubation, extubation should not be performed until plenty of time has passed following resumption of spontaneous breathing and recovery of consciousness. Drainage through the nasal tubes should be thorough. Intermaxillary fixation should not be performed until the patient can breathe deeply, cough, remove oral hemorrhage and secretion, or swallow to the esophagus. This might help prevent the occurrence of pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax, such as in this case. Therefore, our hospital no longer performs intermaxillary fixation after surgery and prevents the oral retention of blood and secretion. Also, we have made note that excessive positive pressure ventilation can cause pneumomediastinum.

In conclusion, patients who experience respiratory difficulty after orthognathic surgery may be suspected of having pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax caused by retained secretion triggering intra-alveolar pressure and alveolar rupture.

Go to :

References

1. Edwards DB, Scheffer RB, Jackler I. Postoperative pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax following orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986; 44:137–141. PMID: 3456021.

2. St-Hilaire H, Montazem AH, Diamond J. Pneumomediastinum after orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004; 62:892–894. PMID: 15218571.

3. Korean Association of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgeons. Textbook of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery. 1998. Seoul: Medical & Dental Publication Co;p. 727–734.

4. Caceres M, Ali SZ, Braud R, Weiman D, Garrett HE Jr. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: a comparative study and review of the literature. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008; 86:962–966. PMID: 18721592.

5. Adwers JR, Hodgson PE, Lynch R. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum. J Trauma. 1974; 14:414–418. PMID: 4823953.

6. Bryant AS, Cerfolio RJ. Sugarbaker DJ, Bueno R, Krasna MJ, Mentzer SJ, Zellos L, editors. Pneumothorax and Pneumomediastinum. Adult Chest Surgery. 2009. China: The McGraw-Hill Companies;p. 917–924.

7. Minocha A, Richards RJ. Pneumomediastinum as a complication of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. J Emerg Med. 1991; 9:325–329. PMID: 1940235.

8. Chen SC, Lin FY, Chang KJ. Subcutaneous emphysema and pneumomediastinum after dental extraction. Am J Emerg Med. 1999; 17:678–680. PMID: 10597088.

9. Haberkamp TJ, Levine HL, O'Brien G. Pneumomediastinum secondary to mandible fracture. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1989; 101:104–107. PMID: 2502755.

10. Chuong R, Boland TJ, Piper MA. Pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema associated with temporomandibular joint surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992; 74:2–6. PMID: 1508503.

11. Macklin CC. Transport of air along sheaths of pulmonic blood vessels from alveoli to mediastinum: clinical implications. Arch Intern Med. 1939; 64:913–926.

12. Wintermark M, Schnyder P. The Mackiln effect: a frequent etiology for pneumomediastinum in severe blunt chest trauma. Chest. 2001; 120:543–547. PMID: 11502656.

14. Wintermark M, Wicky S, Schnyder P, Capasso P. Blunt traumatic pneumomediastinum: using CT to reveal the Macklin effect. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999; 172:129–130. PMID: 9888752.

15. Schulman A, Fataar S, Van der Spuy JW, Morton PC, Crosier JH. Air in unusual places: some causes and ramifications of pneumomediastinum. Clin Radiol. 1982; 33:301–306. PMID: 7075135.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download