Abstract

A 12-year-old boy with ventricular septal defect and patent ductus arteriosus was presented to the operating room. Upon clamping the patent ductus arteriosus, the femoral arterial pressure curve was lost; however, it returned upon unclamping. Upon further dissection, an interrupted aortic arch was found between the left subclavian artery and patent ductus arteriosus. The surgery was discontinued for further evaluation.

As technical advances in echocardiography has enabled the diagnosis of congenital heart disease, simple lesions such as an uncomplicated atrial septal defect (ASD), ventricular septal defect (VSD) and patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) are diagnosed without a preoperative catheterization [1-3]. The choice of the artery to be cannulated for arterial blood pressure (BP) monitoring during surgery depends on the cardiovascular anatomy of the patient.

We report a case of undiagnosed interrupted aortic arch (IAA) recognized during ligation of PDA with loss of femoral BP in a 12-year-old boy presented to the operating room with VSD and PDA.

A 12-year-old boy with exertional dyspnea was admitted to a free clinic. Systolic murmurs on auscultation led to echocardiography, and VSD was diagnosed. On physical examination, moderate respiratory distress with intercostals retraction and a grade 3/6 systolic murmur with P2 accentuation were noted. A chest roentgenogram demonstrated moderate cardiomegaly with increased pulmonary vascular marking and prominent pulmonary conus. Transthoracic echocardiography showed a confluent perimembranous VSD 18 mm in diameter, right ventricular hypertrophy with severe pulmonary hypertension, and a PDA 8 mm in diameter.

To monitor BP and arterial blood sample, 22 G and 20 G catheters were inserted to the radial artery and the femoral artery respectively, under general anesthesia. The femoral mean BP was 5-10 mmHg lower than that of the radial artery. A 5 F central venous catheter was inserted through the right internal jugular vein. After the median sternotomy, the ductus arteriosus was dissected. Upon clamping the PDA, the femoral BP curve was lost and promptly restored when the clamp was removed. Further dissection of the aortic arch and both pulmonary arteries demonstrated an atretic isthmus of the aorta between the left subclavian artery and the PDA (Interrupted aortic arch type A). Intracardiac pressures were directly measured in the surgical field. The right ventricular pressure and pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP) were 64/15 mmHg and 72/46 mmHg when radial and femoral BP were 100/60 mmHg and 80/40 mmHg, respectively. The surgery was discontinued and the patient was sent to the intensive care unit (ICU) after chest closure for further evaluation. In the ICU, physical examination was performed again and a slight clubbing of the toe nails was observed but the finger nails were normal.

IAA is a rare congenital anomaly representing approximately 1% of congenital heart disease. More than 90% of untreated patients die in the first year of life and the operative mortality increases with age at the time of surgery [4]. More than 98% of the cases also have associated cardiac anomalies and the two most common are VSD and PDA. In fact, IAA commonly occurs together with VSD and PDA as a triad [4,5]. Although improving, outcomes of IAA continue to be associated with high mortality both before and immediately after repair [5]. IAA is usually recognized earlier in the patient's life. Patients with IAA who also have VSD and PDA in previous cases were diagnosed before the first 5 years of their lives. In a case report of a 31-year-old pregnant woman with untreated IAA, VSD and PDA, Eisenmenger syndrome was evident [6]. In this case, the PAP measured in the operation field was close to the systemic BP, which suggested organic pulmonary hypertension.

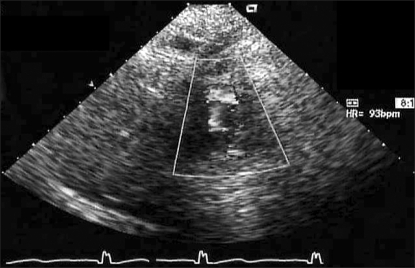

The diagnosis of congenital heart disease is difficult due to its complex anatomy and varying hemodynamic status. Since the length of an open heart operation is an important determinant of its successful outcome, unexpected intraoperative findings should be carefully avoided by a proper preoperative diagnostic evaluation. With the evolution of two-dimensional image with flow and pressure dynamics from Doppler echocardiography, cardiac catheterization is performed in select patients. Studies on diagnostic accuracy of echocardiography confirmed the adequacy of the technique, which was comparable to the adequacy of catheterization [1,3]. However, there are some conditions that even an experienced pediatric echocardiographer with a high-quality image find difficult to recognize. Usually, IAA is not difficult to detect with echocardiopraghy but in this case, the high left parasternal view and the suprasternal notch view had a poor echocardiographic window, and IAA could not be observed (Fig. 1). The abnormality in the aortic arch should have been suspected because of low BP of the lower extremities and clubbing of the toe nails but with the technical advancement of diagnostic tools, physical examination of the patient is often overlooked and the diagnosis heavily depends on study results. All these may have resulted in the misdiagnosis of the patient.

During congenital heart surgery, the choice of arterial line for BP monitoring depends mostly on the anatomy of the patient and the surgical plan. Except for simple conditions such as uncomplicated ASD/VSD, both the right radial artery and the femoral artery should be cannulated and monitored simultaneously. Both arteries were monitored because the patient in this case had right ventricular hypertrophy with severe pulmonary hypertension. Cannulation of the femoral artery carries risk of complications such as arterio-venous fistula. However, the radial arteries of small children can easily become damaged or become non-functional during surgery with frequent sampling. In addition, patients with congenital heart disease may have undiagnosed anomalies in their circulatory system as in this case.

This case demonstrates the usefulness of dual arterial monitoring system including femoral BP as well as the importance of the traditional physical examination as a part of preoperative evaluation in pediatric open heart surgery.

References

1. Pfammatter JP, Berdat PA, Carrel TP, Stocker FP. Pediatric open heart operations without diagnostic cardiac catheterization. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999; 68:532–536. PMID: 10475424.

2. Freed MD, Nadas AS, Norwood WI, Castaneda AR. Is routine preoperative cardiac catheterization necessary before repair of secundum and sinus venosus atrial septal defects? J Am Coll cardiol. 1984; 4:333–336. PMID: 6736474.

3. Sreeram N, Colli AM, Monro JL, Shore DF, Lamb RK, Fong LV, et al. Changing role of non-invasive investigation in the preoperative assessment of congenital heart disease: a nine year experience. Br Heart J. 1990; 63:345–349. PMID: 2375896.

4. Reardon MJ, Hallman GL, Cooley DA. Interrupted aortic arch: brief review and summary of an eighteen-year experience. Tex Heart Inst J. 1984; 11:250–259. PMID: 15227058.

5. Oosterhof T, Azakie A, Freedom RM, Williams WG, McCrindle BW. Associated factors and trends in outcomes of interrupted aortic arch. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004; 78:1696–1702. PMID: 15511458.

6. Chou WR, Kuo PH, Shih JC, Yang PC. A 31-year-old pregnant woman with progressive exertional dyspnea and differential cyanosis. Chest. 2004; 126:638–641. PMID: 15302756.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download