Introduction

Incidences of cancer in Korea showed a rapid increased from 1999 to 2009, as indicated by a 3.4% annual increase for both genders: 1.6% in men and 5.5% in women. A high rate of cancer incidence was reported in Korea, and for the year 2009, more than 178,000 people were diagnosed with cancer; nearly 70,000 deaths resulting from cancer were reported. This accounts for 28% of all deaths, despite the fact that age-standardized mortality rates have decreased since 2002 [

1].

In 1996, the Korean government implemented the 10-Year Plan for Cancer Control. The first-term was conducted from 1996 to 2005 and the second-term started in 2006. The plan includes primary, secondary, and tertiary cancer prevention and a cancer registry. One objective of the program is establishment of early cancer screening for all Koreans through enhanced medical service coverage. To achieve this objective, the National Cancer Screening Program (NCSP) was established by the Korean government in 1999. Since then, both the target population and types of cancer covered have expanded. Between 1999 and 2001, the NCSP provided Medical Aid recipients with free screening for cancer of the stomach, breast, and cervix. National Health Insurance (NHI) beneficiaries in the lower 20% income bracket were included in the NCSP in 2002, and, in 2003, the NCSP was expanded to NHI beneficiaries in the lower 30% income bracket and a screening program for liver cancer was added to the NCSP. Screening for colorectal cancer was included in 2004, and, since 2006, the NSCP has provided Medical Aid recipients and NHI beneficiaries in the lower half of the income bracket with free-of-charge screenings for stomach, liver, colorectal, breast, and cervical cancer. Individuals in the upper 50% of NHI beneficiaries can also receive screening services for these five cancers from the NHI Corporation, and 90% of the costs are subsidized [

2-

6].

In Korea, both the organized cancer screening program and opportunistic cancer screening are widely available. Organized screening programs have nationally implemented guidelines defining a target population, screening interval, and follow-up strategies. In terms of screening items, screening method, and intervals between screenings, a variety of options are available through oopportunistic screening programs, which are based on individual decisions or recommendations from health-care providers. All fees are paid entirely by users without governmental subsidy [

7]. This study was conducted in order to report on trends in rates of cancer screening, including both organized and opportunistic screening within the Korean population.

Materials and Methods

Data from the Korean National Cancer Screening Survey (KNCSS), collected from 2004 to 2011, were used in this study. The KNCSS is a nationwide, population-based, cross-sectional survey conducted annually by the National Cancer Center in Korea. Stratified multistage random sampling, based on resident registration population data, was conducted according to geographic area, age, and gender. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Cancer Center, Korea (approval number: NCCNCS-08-129).

In 2004, computer-assisted telephone interviews were conducted for collection of data. Since 2005, face-to-face interviews have been conducted by a professional research agency. The number of enumeration districts was designated in proportion to population size and the final study clusters were randomly selected. Five to eight households in an urban area and 10-12 households in one rural area were chosen randomly.

Subjects were recruited by door-to-door contact, and at least three attempts at each household were made. According to the guidelines for organized cancer screening, the eligible population consists of cancer-free men who are 40 years old and over, and women who are 30 years old and over (see

Appendix 1). Men and women who were 40 years old and over were eligible to undergo gastric cancer screening, men and women who were 50 years old and over were included for colorectal cancer screening, women who were 40 years old and older were eligible to undergo breast cancer screening, and women who were 30 years old and over were included for cervical cancer screening. Screening for liver cancer was restricted to people who were 40 years old and over, including those in high-risk groups, such as those with hepatitis B virus surface antigen or hepatitis C virus antibody positive, or liver cirrhosis. One person was selected from each household; if there were more than one eligible person in the household, the person whose date of birth was closest to the study date was selected.

Between 2005 and 2011, rates of response ranged between 34.5% and 58.5%. Following an explanation of the aim and confidentiality of the survey, informed consent was obtained from all participants. Using a structured questionnaire, participants were asked about sociodemographic characteristics, as well as their experience with cancer screening for five common cancers (stomach, liver, colorectal, breast, and cervix uteri). Questions included: "Have you ever undergone (cancer type) screening?" and "Which screening method have you experienced?" For the interval between screenings, the question was: "When did you last undergo (cancer type) screening with this method?", and, regarding reasons for undergoing screening or not undergoing screening, the question was: "What are your primary reasons for undergoing screening or not undergoing screening?" General sociodemographic characteristics of survey respondents for each year are shown in

Appendix 2.

Calculation of cancer screening rates was based on two definitions. "Lifetime screening" was defined as having experienced each type of screening test. Rates were calculated as the proportion of subjects within the target age range for each type of cancer screening examined. The "screening with recommendation" category was assigned to participants who had undergone screening tests according to organized cancer screening guidelines (

Appendix 1). However, in colorectal screening, respondents who underwent colonoscopy, double-contrast barium enema (DCBE), or fecal occult blood test (FOBT) within five, five, or one years, respectively, before 2009, and within ten, five, and one years, respectively, in 2009 and afterward were regarded as having undergone screening with recommendation. Rates were calculated as the proportion of subjects within the target age range for each type of cancer screening examined in accordance with recommendation. Changes in annual lifetime screening rates and screening rates with recommendation were calculated as the annual percentage change, within 95% confidence intervals (CIs) [

8].

Calculation of screening rates according to gender, age, and income was also performed. Monthly household income was regarded as income level and was subgrouped into three tertiles for each year. Due to an inadequate number of individuals within the high-risk group, as well as unstable results showing wide 95% CIs, liver cancer was excluded from subgroup analysis.

Results

Lifetime screening rates and screenings with recommendation showed a continuous increase from 2004 until 2011. On average, between 2004 and 2011, the rate of screening with recommendation showed an annual increase of 4.2% for gastric cancer, 1.1% for liver cancer, 2.2% for colorectal cancer, 4.0% for breast cancer, and 0.2% for cervical cancer (

Table 1). Significant increasing trends were observed in the rates of gastric, colorectal, and breast cancer screening, but not liver or cervical cancer screening. Despite observance of an increasing trend between 2004 and 2010, screening rates did not show an increase in 2011, and a stable pattern was observed instead compared to 2010 (

Table 1). Trends differed according to screening methods. The average rate of increase of screenings using upper endoscopy was nearly twice as fast as that for screenings using upper gastrointestinal series (4.3% per year vs. 1.9% per year, respectively). Regarding colorectal cancer, on average, the rate of screening using FOBT showed a more rapid increase, compared with the rate of screening using colonoscopy or DCBE (3.1% per year vs. 1.6% per year, 0.4% per year, respectively).

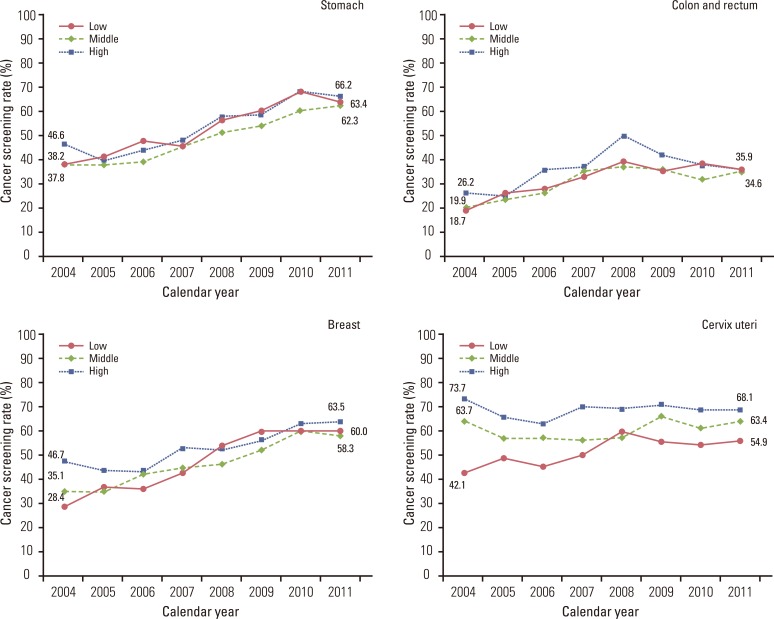

Screening with recommendation of stomach cancer showed a significant increase, while that of colorectal cancer among men showed a plateau after 2009. In women, despite an increase in the rate of screening with recommendation for stomach and breast cancer, the trend of cervical cancer uptake according to guidelines plateaued in 2009, and a decreasing tendency was observed for colorectal cancer after 2008 (

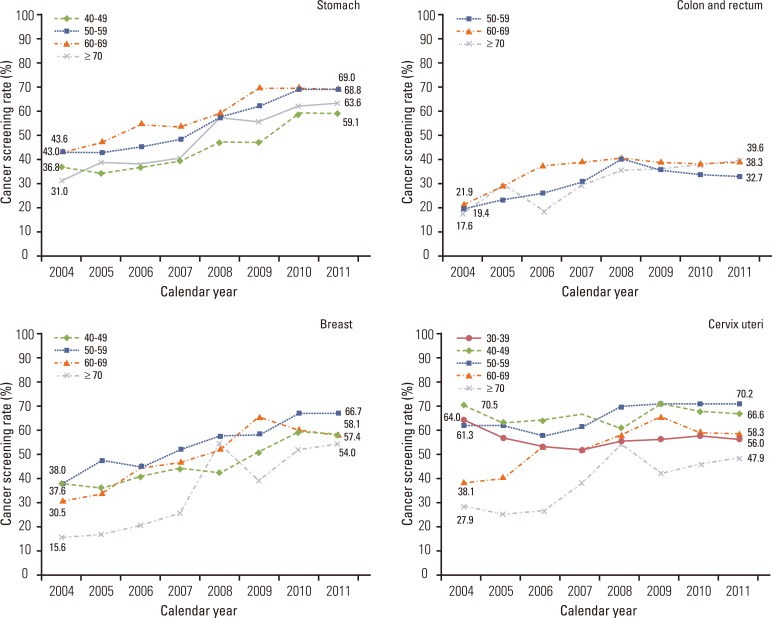

Fig. 1). According to age group, overall rates of screening with recommendation showed an increase in all age groups and all four types of cancer, except for cervical cancer screening among women in their thirties. The most noticeable increases for gastric cancer screenings were among subjects over the age of 70, and for rates of breast cancer screening among subjects over the age of 70, both of which showed steep increases when compared to other groups (

Fig. 2). Rates of screening for stomach and breast cancer have shown a steady increase at all income levels, and differences in screening rates among income groups have shown a decrease. Screening rates for colorectal cancer peaked in 2008, followed by a pattern of decrease in all income groups, while gaps between groups showed a decrease. The rate of cervical cancer screening showed a plateau in 2009; however, differences in screening rates among income levels showed a decrease (

Fig. 3).

Discussion

Rates of lifetime screening and screening with recommendation for five major cancers, particularly stomach and breast cancer, have shown a continuous increase since 2004. Rates of screening with recommendation for stomach, breast, and cervical cancer, for which organized screening services began in 1999, exceeded 60% after 2010. Under the second-term 10-Year Plan for Cancer Control, one of the goals was to achieve an increase in rates of cancer screening with recommendation to 70% by 2015 [

9]. Screening rates for these three cancers have come close to reaching that goal. However, the start of services for screening of liver and colorectal cancer was relatively recent, and lower screening rates were observed. Overall rates of cancer screening across age and income groups, particularly for breast cancer, showed an increase.

In the US, where opportunistic screening is dominant [

10], the screening rate for biannual breast cancer mammography among women who were 40 years old and over was 67% in 2005, and the rate for annual screening was 51% and 53% for 2005 and 2008, respectively [

10,

11]. These rates are similar to those reported in Korea. The rate of screening for breast cancer in the US showed an increase until 2000, reached a plateau, where it remained until 2003, and then showed a decrease. These trends were observed in all races and education groups. However, absolute percent differences in the use of breast cancer screening services, according to race and level of education, remained similar between 1987 and 2005 [

11]. In the US, the rate of females who were 18 years old and over and had undergone screening for cervical cancer within a period of three years showed a slight increase until 2000, and then fell. In 2008, the rate was 78%, which was higher than the rate reported in Korea. As with breast cancer screening, no change in absolute differences in rates of cervical cancer screening according to education was observed [

12]. Rates of screening for colorectal cancer were significantly higher in the US than in Korea. Regarding the screening method, in contrast with Korea, where FOBT and colonoscopy showed a similar share of total colorectal cancer screening, in the US, the rate of screenings using colonoscopy was much higher than for those using FOBT [

13]. In Korea, the rate of colorectal cancer screening using FOBT showed a more rapid increase when compared with other methods, which may be due to guidelines of the organized cancer screening program, which designated that only cases showing abnormal results on FOBT could be subsidized for the cost of colonoscopy or DCBE. Considering that we regarded those who underwent colonoscopy within a period of five years as having undergone screening with recommendation, which was more strict than the organized screening guidelines before 2009, due to changes in the questionnaire, the average rate of increase of colonoscopy screening could be lower than we calculated.

In the UK, where screening for breast and cervical cancer are included in an organized program, 73.3% of women underwent mammography in 2009 and 2010 [

14]. Relatively stable trends in breast cancer screening were observed for women under 65 years of age; however, an increase was observed in the 65 and over age group [

15]. Five-year coverage of cervical cancer screening was 79% in 2010 and 2011 for women 25-49 years of age; this trend tended toward stability. However, among women 50-64 years of age, while 78% underwent screening, the rate showed a declining tendency [

16]. In contrast to the lower rates of colorectal cancer screening in Korea, where screening started later, nationwide coverage for colorectal cancer screening was achieved in the UK [

17].

In a study conducted in Japan, the rate of screening for gastric cancer was 11.8%, with a declining trend since the early 1990s. The screening rate for colorectal cancer showed a gradual increase, reaching 18.8% in 2007, and the screening rate for breast cancer was 14.2%, trending toward a gradual increase. The screening rate for cervical cancer began a decline during the early 1990s, and then began to increase again in the mid 2000s. In contrast with Korea, screening for lung cancer is included in Japan's organized screening program, and the screening rate showed a continuous increase until the mid 2000s, and then showed a slight decrease, reaching 21.6% in 2007 [

18].

This study has several limitations. First, our results were reliant on self-reported data. Although survey data from self-reported interviews may have introduced a bias, findings from many studies have demonstrated the reliability of self-reported histories of cancer screening, which have shown good agreement with medical records [

19-

21]. Second, the rate of response in our study ranged from 34.5% to 58.5%; however, compared with other nationwide studies conducted in Korea, in which rates of response were less than 50% [

22,

23], in the Korean context, our rate of response can be considered acceptable.

Several improvements in secondary prevention of cancer have been achieved through implementation of the National Cancer Control Plan. The lifetime screening rate and screening rate with recommendation have shown an increase; in addition, socioeconomic disparities, such as income, which affect use of cancer screening services, have begun to show a decrease. In comparison, in the US, rates of screening have shown an increase, however, differences among socioeconomic levels have not decreased [

11-

13]; both the increasing rates of screening and decreasing disparities shown in our results from Korea might reflect the success of the National Cancer Control Plan. Although we did not exclude the effect of opportunistic screening, results suggest that the NCSP has played an important role in the rapid increase of cancer screening services in Korea. Based on our results, we found that use of an organized screening program has shown a rapid increase and covers more than 70% of cancer screening usage (data not shown).

In order to increase the rate of cancer screening, efforts have been launched from both the national and private sector. Invitation letters were sent to the eligible members of the population for the NCSP and efforts were made at public health centers to encourage increased participation in the organized cancer screening program by eligible members of the population. In addition, opportunistic cancer screening programs featuring various options and equipped with diagnostic tools have been developed in private general hospitals.

The rate of screening for colorectal, breast, and cervical cancer is lower in Korea than in Western countries, such as the US [

10-

13] and UK [

14-

17], and lower than the average of member countries in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) for breast cancer screening [

24]; however, for cervical cancer screening, the rate is slightly higher than the average of OECD members [

25]. In order to detect cancer at an early stage and to reduce mortality through timely treatment, it is important to follow recommendations for screening. Target cancers included in the organized program are relatively common, and, if diagnosed and treated early, are completely curable. Therefore, greater effort should be dedicated to increasing rates of screening and to decreasing the cancer-related health-care burden in Korea.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download