Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to analyze the efficacy and toxicity of gemcitabine plus platinum chemotherapy for patients aged 70 years or older with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Materials and Methods

We reviewed the records of stage IIIB, IV NSCLC patients or surgically inoperable stage II, IIIA NSCLC patients who were aged 70 years or older when treated with gemcitabine (1,250 mg/m2) plus cisplatin (75 mg/m2) or carboplatin (AUC5) chemotherapy from 2001 to 2010 at Seoul St. Mary's Hospital, Uijeongbu St. Mary's Hospital and St. Vincent's Hospital. Gemcitabine was administered on days 1 and 8, and cisplatin or carboplatin was administered on day 1. Treatments were repeated every 3 weeks for a maximum of 4 cycles.

Results

The median age of the 62 patients was 73.5 years (range, 70 to 84 years). Forty-one (66%) patients exhibited comorbidity. The mean number of treatment cycles was 3.9. The compared average relative dose intensity of gemcitabine plus platinum chemotherapy was 84.8%. The median progression-free survival and overall survival (OS) were 5.0 months and 9.4 months, respectively. Reduced Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (none vs. ≥1) and weight loss (<5% vs. ≥5%) after treatment were found to have a significant effect on OS (p=0.01).

Go to :

In 2008, 18,774 cases of non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) were diagnosed in Korea, representing 10.5% of all cancer incidence [1]. Thirty-four percent of those diagnosed with NSCLC were 70 years or older in age. Although mortality from NSCLC has decreased in patients aged 60 years and younger, it has increased in those aged above 70 years. In the past, the elderly have often been excluded from clinical trials because of age-related decrease in organ function, such as reductions in renal and hepatic function, which potentially increase the risk of chemotherapy-induced toxicity. Unfortunately, elderly patients have been empirically undertreated even if they had a good performance status because of the widespread preconception that cancer in older patients is less aggressive and that older patients are inherently intolerant to chemotherapy. In addition, elderly patients have severe cardiopulmonary comorbidity [2,3].

Elderly patients show a number of age-related health issues that can affect their tolerance to cancer treatments. Problems with maintaining fluid homeostasis may develop because of decreased cardiovascular reserve following increased arterial stiffening and systolic blood pressure and decreased maximal heart rate. Moreover, decreased diffusion capacity, vital capacity, and one-second forced expiratory volume may result in decreased pulmonary function. Elderly patients are more sensitive to neurologic complications after cancer treatment because of decreased brain mass and cerebral blood flow. The elderly are also more likely to suffer from prolonged gastrointestinal toxicity owing to diminished turnover of gastrointestinal mucosa. In addition, renal and hepatic blood flow decreases with aging; this may affect the clearance of chemotherapeutic agents [4,5].

The development of medicine and improvement in nutritional status resulted in the increased performance status of elderly patients over the last decade in Korea. It may be difficult to determine benefits and tolerance to chemotherapy based on age alone. However, elderly patients who are physiologically younger than their peers are good candidates for platinum-based combination chemotherapy. Therefore, we analyzed the efficacy and toxicity of platinum plus gemcitabine chemotherapy in advanced NSCLC patients aged 70 years or older.

Go to :

We retrospectively reviewed the records of patients aged 70 years or older, who were enrolled in this study if they had been histologically or cytologically diagnosed with stage IIIB, IV NSCLC or had recurrent or surgically inoperable stage II, IIIA NSCLC. A total of 543 patients were diagnosed as NSCLC and 207 patients received anti-cancer treatment between 2001 and 2010 at Seoul St. Mary's Hospital, Uijeongbu St. Mary's Hospital and St. Vincent's Hospital in Korea. To be eligible, patients had to have 1) measurable lesions; 2) an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0, 1, or 2; and 3) adequate organ function. We excluded patients with clinically overt brain metastases and those who had previously received chemotherapy into five years. Patients who had undergone radiotherapy were eligible if the radiation treatment was completed at least 2 weeks before enrollment. Cancer staging was performed according to the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer.

Gemcitabine was administered at a dose of 1,250 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8. Cisplatin was administered at a dose of 75 mg/m2 on day 1. Carboplatin was administered at a dose of AUC5 on day 1. The carboplatin dose was calculated using the Chatelut formula [6]. Selection of cisplatin or carboplatin administration during the first cycle was determined by the physician. If cisplatin induced grade 3 or higher for nephrotoxicity, ototoxicity, or neurotoxicity, it was replaced with carboplatin. The administration of both drugs was reduced or omitted in the case of hematologic toxicity according to the dosage adjustment criteria: 80% of the full doses of gemcitabine and cisplatin/carboplatin were given if the absolute granulocyte count was between 500/mm3 and 100/mm3 and/or the platelet count was between 50,000/mm3 and 75,000/mm3. Chemotherapy was delayed by 1 week if the absolute granulocyte count was below 500/mm3 and/or the platelet count was below 50,000/mm3. Next chemotherapy was omitted if it was delayed by 2 weeks. This regimen was repeated every 3 weeks for a minimum of 4 cycles per patient unless disease progression was detected or there were unacceptable toxicities. Second-line treatment was determined by the physician.

Before each treatment cycle, patient history was obtained and physical examination, complete blood cell count, and blood chemistry were performed. Objective responses were evaluated by computerized tomography every 2 treatment cycles. The response evaluation was performed according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (ver. 1.1). The best response for each patient was used for analysis. The objective response rate (ORR) represents the percentage of patients that had a partial response (PR) or a complete response (CR). The disease control rate (DCR) was defined as the percentage of patients that had a PR, CR, or stable disease. Occurrence of cancer-related death before response evaluation was defined as progressive disease. Toxicity was assessed by the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (ver. 3.0). For toxicity analysis, the worst data for each patient in all cycles of treatment were used.

The delivered dose intensity was the total dose delivered over the entire period of chemotherapy. The relative dose intensity (RDI) was the ratio of delivered dose intensity to the reference standard dose and was expressed in percentage. Overall survival was defined as the time between the date of treatment initiation and the last date that the patient was known to be dead or alive. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time from the date of treatment initiation to disease progression or to death from disease progression.

Fisher's exact test and Student's t-test were used to compare patient characteristics. Fisher's exact test was used to compare response rates, whereas Student's t-test was used to compare average dose intensities and levels of toxicity. Survival estimates and comparisons were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test, respectively. A univariate Cox proportional hazards model was used to summarize the association between clinical and pathological characteristics. Variables that showed weak evidence of association with the outcome (p<0.20) were considered for inclusion into a multivariable Cox proportional hazards model. p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS ver. 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Go to :

The record of 62 patients with NSCLC was reviewed retrospectively. The study sample consisted of 42 men (67.7%) and 20 women (32.3%) aged 70 to 84 years (mean, 73.5 years). The tumor histology was adenocarcinoma in 33 patients, squamous cell carcinoma in 20, large cell carcinoma in 2, poorly differentiated carcinoma in 3, pleomorphic carcinoma in 3, and mucoepidermoid carcinoma in 1 patient. Three patients (4.8%) with stage IIB and IIIA were eligible for the study because they were inoperable. The most frequent comorbidity was cardiovascular disease (hypertension, coronary artery disease, or congestive heart failure), which was reported in 38.7% of patients. The second most common comorbidity was endocrine disease (diabetes mellitus or hypothyroidism). Seven patients had previously received anti-cancer treatment due to ovarian cancer, prostate cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, head and neck cancer, stomach cancer, and bladder cancer; 2 ovarian cancer patients received surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy. Hepatocellualr carcinoma, glottis cancer, prostate cancer, bladder cancer, stomach cancer patients received surgery alone. All 7 patients were in complete remission after more than 5 years of the NSCLC being diagnosed. These data are summarized in Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with non-small cell lung cancer

Three patients aged 70 to 74 years (7%) discontinued treatment because of disease progression. Fifteen patients (24%) discontinued treatment due to toxicity and a decrease in performance status. Eleven of these patients were 70 to 74 year in age, whereas 4 were 75 years and older. The mean duration of treatment for patients who were 70 to 74 years of age and 75 years or older was 3.8 months and 2.5 months, respectively. Nine patients (6 belonged to the 70 to 74 year old group and 3 to the group 75 years or older group) initially treated gemcitabine-carboplatin chemotherapy. For 5 patients (70 to 74 years of age), cisplatin was replaced with carboplatin because of ototoxicity (3 patients), nephrotoxicity (1 patient), and neurotoxicity (1 patient). The average RDI of all patients was 84.8±21.0%. The average RDI between patients aged 70 to 74 years and those older than 75 years was not significantly different (p=0.12). These data are summarized in Table 2.

Average relative dose intensity (RDI) of gemcitabine/platinum chemotherapy

The ORR and DCR were not significantly different (p=0.20 and p=0.66, respectively) between the two patient groups: those of the 70 to 74 year old patients were 38.6% and 86.4%, and those of the patients aged 75 years or older were 16.7% and 94.4%, respectively. The response evaluations are summarized in Table 3.

Tumor responses to gemcitabine/platinum chemotherapy

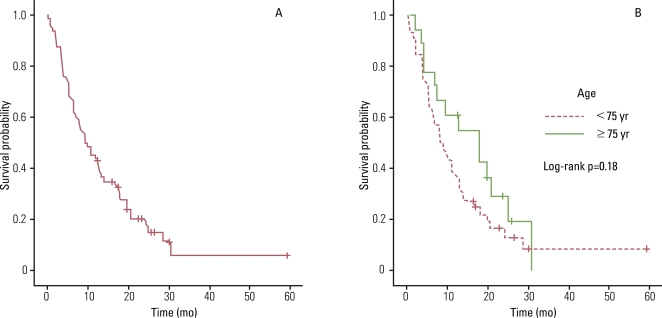

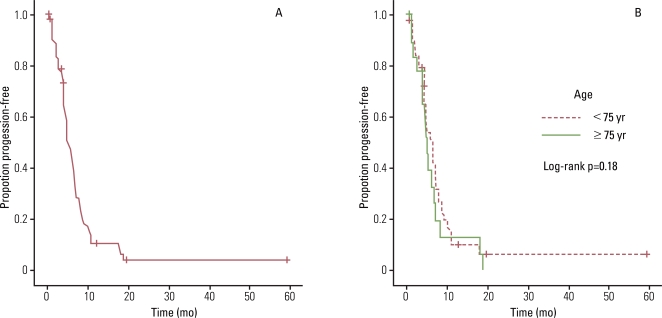

The median overall survival (OS) and PFS were 9.4 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 6.72 to 13.14 months) and 5.0 months (95% CI, 3.64 to 6.42 months), respectively. Analysis of the curve for OS (8.1 months vs. 17.7 months, p=0.18; Fig. 1) and PFS (5.9 months vs. 4.9 months, p=0.44; Fig. 2) revealed that there was no significant difference between patients aged 70 to 74 years and those older than 75 years. The overall 1-year survival rate was 42%. When patients were separated into younger and older age groups, the 1-year survival rate was 35% and 55%, respectively.

Post-therapeutic weight loss (<5% vs. ≥5%), post-therapeutic glomerular filtration rate (GFR) loss (<16% vs. ≥16%), and average RDI of platinum (<80% vs. ≥80%) were all associated with PFS, as determined by univariate analysis. After adjustment of the variables, multivariable analysis revealed that GFR loss (hazard ratio [HR], 0.37; 95% CI, 0.17 to 0.80; p=0.01) remained as a significant factor affecting PFS.

The performance status change (none vs. >1), post-therapeutic weight loss (<5% vs. ≥5%), post-therapeutic GFR loss (<16% vs. ≥16%), average RDI of gemcitabine (<85% vs. ≥85%), and average RDI of platinum (<80% vs. ≥80%) were all associated with OS, as determined by univariate analysis. After adjustment of the variables above, multivariable analysis revealed that the performance status change (HR, 2.65; 95% CI, 1.27 to 5.54; p=0.01) and weight loss (HR, 0.26; 95% CI, 0.09 to 0.79; p=0.01) remained as significant factors affecting OS (Tables 4 and 5).

Hazard ratios for progression-free survival (n=62)

Hazard ratios for overall survival progression-free survival (n=62)

Grade 3 to 4 febrile neutropenia was reported for 6 patients in 70 to 74 year old group and for 1 patient from the group aged 75 years and older. Hospitalization due to febrile neutropenia was not significantly different between the younger group (9.0±3.6 days) and the older group (6.0±4.2 days) (p=0.50).

Death during treatment period was reported for 3 patients only in 70 to 74 year old group. One patient died as a result of catheter-related sepsis after 1 cycle of chemotherapy and another patient expired because of acute respiratory distress syndrome induced by aspiration pneumonia after 6 cycles of treatment. Another patient expired due to acute kidney injury after 1 cycle of treatment. Three patients refused further treatment after 4 cycles of treatment after experiencing grade 3 vomiting and general weakness.

There was no significant difference between the groups in hematologic or non-hematologic toxicity, or in the usage of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and transfusion of packed red cell and platelets. Pre- and post-therapeutic weight change was calculated and a significant difference was observed (p=0.047). After treatment, 37 patients (29 belong to the 70 to 74 year old group, 8 patients to the group 75 years or older) showed decrease in weight of more than 5%.

The difference in the pre- and post-therapeutic GFR values was calculated. The GFR of 38 patients (25 patients belong to the 70 to 74 year old group and 13 patients to the 75 years or older group) decreased by more than 16% after treatment which is a decrease of 1 grade or more according to the definition of chronic kidney disease, but this change was not significantly different (p=0.51). Table 6 shows the toxicity profile.

Toxicity profile of gemcitabine/platinum chemotherapy

Ten patients were lost to follow up after the first-line treatment. Thirty-one patients failed in response to primary treatment or experienced disease progression after first-line chemotherapy. Fifteen patients (24.2%) were treated by epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, 10 (16.1%) by docetaxel, 4 (6.5%) by pemetrexed, 1 (1.6%) by paclitaxel-carboplatin chemotherapy and 1 (1.6%) by clinical trial of the novel target agent ticilimumab.

Go to :

We evaluated the efficacy and toxicity of gemcitabine and platinum chemotherapy for patients aged 70 years or older with advanced NSCLC. In our study, 66.1% of patients had underlying comorbidity including cardiovascular disease, endocrine disorders and their combination. The average RDI and mean number of treatment cycle for gemcitabine and platinum chemotherapy were 84.8% and 3.94 cycles, respectively. The ORR, 1-year survival rate and median OS were 32.2%, 42%, and 9.4 months, respectively. These results were similar to those of meta-analysis for gemcitabine-containing combination chemotherapy in advanced NSCLC showing ORR of 30%, 1-year survival rate of 37%, and median OS of 8.7 months [7,8]. Also, a phase II clinical trial using modified schedules and attenuated doses of cisplatin reported ORR of 35%, 1-year survival rate of 35%, and median OS of 11 months [9,10]. However, the response rate of patients who were 70-74 years in age was 21.9% higher than that of patients aged 75 years or older (38.6% vs. 16.7%). This difference between the two groups may be due to a reduction in average RDI in the patients aged 75 years or older.

In the multivariate analysis, GFR loss remained a significant prognostic factor affecting PFS. Post-therapeutic performance status change and weight loss were significant prognostic factors affecting OS. Platinum-related severe nausea/vomiting and anorexia were more frequently observed in patients with a significant change in performance status.

In our study, grade 3 to 4 neutropenia and thrombocytopenia were observed at a frequency of 54.8% and 40.3%, respectively. This incidence was much higher than the meta-analysis of gemcitabine-containing chemotherapy for advanced NSCLC, which reported 25% of grade 3 to 4 neutropenia and 18% of thrombocytopenia [8]. This suggests that active supportive care and careful monitoring should be given to elderly NSCLC patients because decreased GFR and weight loss were significant factors affecting PFS and OS. These patients were also more vulnerable to chemotherapy-induced myelotoxicity than younger patients.

Although recent research have revealed that the pharmacokinetics of cisplatin does not differ depending on age [11], clinical data showed that elderly patients experienced more profound myelotoxicity than younger patients [12,13]. These studies suggested that a reduction in RDI arising from GFR loss induced by cisplatin resulted in shortening of PFS.

A phase III multicenter clinical trial for advanced NSCLC in elderly patients reported that single-agent vinorelbine improved the quality of life and survival relative to supportive care alone [14]. However, other clinical studies demonstrated that the combination of vinorelbine with gemcitabine did not improve survival rate or quality of life compared to an individual agent [15,16]. Based on the results from these large-scale randomized comparative clinical studies, single-agent chemotherapy has been favored as systemic treatment for elderly NSCLC patients.

Recently, the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database at the National Cancer Institute in US evaluated the use of various chemotherapies in adults aged older than 65 years with advanced NSCLC. Only 25.8% of patients who received first-line chemotherapy showed an increased adjusted 1-year survival rate as compared to those that received no chemotherapy (27.0% vs. 11.1%). On the contrary, the use of platinum-based combination chemotherapies resulted in an increased 1-year survival rate relative to single-agent chemotherapies (30.1% vs. 19.4%) [17]. The results of an interesting phase III clinical trial (IFCT-0501) were presented at the 2010 annual meeting of American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO). A total of 451 adults aged 70 to 89 years were randomized for treatment with single-agent chemotherapy (gemcitabine or vinorelbine) or combination chemotherapy (monthly carboplatin plus weekly paclitaxel). Three hundred and thirteen patients were analyzed for anti-tumor efficacy and toxicity of different treatment arms. The OS and the PFS were significantly longer in the combination arm. Although hematologic toxicities were more common in the combination arm, there was no significant difference in early deaths [18].

Based on our result and recent reports, we recommend that the dose of platinum plus gemcitabine chemotherapy be reduced by 15% at the beginning time of treatment for advanced NSCLC patients who are older than 70 years. In addition, prospective clinical trials are required to determine the appropriate doses and scheduling of platinum-based chemotherapy in healthy elderly patients with NSCLC.

Go to :

Oncologists ought to focus on careful monitoring of chemotherapy-induced toxicity, especially for elderly patients. Moreover, strong supportive care should be given to elderly NSCLC patients because weight loss and decreased GFR ultimately leads to poor clinical outcome. Gemcitabine plus platinum combination chemotherapy for elderly NSCLC patients with good performance status seems to be one of the effective treatment options with an acceptable level of toxicity on the assumption that adequate dose reduction and careful monitoring in advance are constituted.

Go to :

References

1. Jung KW, Park S, Kong HJ, Won YJ, Lee JY, Park EC, et al. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2008. Cancer Res Treat. 2011; 43:1–11. PMID: 21509157.

2. Lewis JH, Kilgore ML, Goldman DP, Trimble EL, Kaplan R, Montello MJ, et al. Participation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2003; 21:1383–1389. PMID: 12663731.

3. Hurria A. Clinical trials in older adults with cancer: past and future. Oncology (Williston Park). 2007; 21:351–358. PMID: 17447438.

4. Sawhney R, Sehl M, Naeim A. Physiologic aspects of aging: impact on cancer management and decision making, part I. Cancer J. 2005; 11:449–460. PMID: 16393479.

5. Ferrari AU, Radaelli A, Centola M. Invited review: aging and the cardiovascular system. J Appl Physiol. 2003; 95:2591–2597. PMID: 14600164.

6. Chatelut E, Canal P, Brunner V, Chevreau C, Pujol A, Boneu A, et al. Prediction of carboplatin clearance from standard morphological and biological patient characteristics. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995; 87:573–580. PMID: 7752255.

7. Natale RB. Gemcitabine-containing regimens vs others in first-line treatment of NSCLC. Oncology (Williston Park). 2004; 18(8 Suppl 5):27–31. PMID: 15339056.

8. Schiller JH, Harrington D, Belani CP, Langer C, Sandler A, Krook J, et al. Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002; 346:92–98. PMID: 11784875.

9. Berardi R, Porfiri E, Scartozzi M, Lippe P, Silva RR, Nacciarriti D, et al. Elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. A pase II study with weekly cisplatin and gemcitabine. Oncology. 2003; 65:198–203. PMID: 14657592.

10. Feliu J, Martín G, Madroñal C, Rodríguez-Jaráiz A, Castro J, Rodríguez A, et al. Combination of low-dose cisplatin and gemcitabine for treatment of elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2003; 52:247–252. PMID: 12783203.

11. Minami H, Ohe Y, Niho S, Goto K, Ohmatsu H, Kubota K, et al. Comparison of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of docetaxel and Cisplatin in elderly and non-elderly patients: why is toxicity increased in elderly patients? J Clin Oncol. 2004; 22:2901–2908. PMID: 15254059.

12. Kubota K, Furuse K, Kawahara M, Kodama N, Ogawara M, Takada M, et al. Cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy for elderly patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1997; 40:469–474. PMID: 9332460.

13. Langer CJ, Manola J, Bernardo P, Kugler JW, Bonomi P, Cella D, et al. Cisplatin-based therapy for elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: implications of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group 5592, a randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002; 94:173–181. PMID: 11830607.

14. Gridelli C. The ELVIS trial: a phase III study of single-agent vinorelbine as first-line treatment in elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Elderly Lung Cancer Vinorelbine Italian Study. Oncologist. 2001; 6(Suppl 1):4–7. PMID: 11181997.

15. Frasci G, Lorusso V, Panza N, Comella P, Nicolella G, Bianco A, et al. A Southern Italy Cooperative Oncology Group (SICOG) phase III trial. Gemcitabine plus vinorelbine yields better survival outcome than vinorelbine alone in elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2001; 34(Suppl 4):S65–S69. PMID: 11742706.

16. Gridelli C, Perrone F, Gallo C, Cigolari S, Rossi A, Piantedosi F, et al. Chemotherapy for elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: the Multicenter Italian Lung Cancer in the Elderly Study (MILES) phase III randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003; 95:362–372. PMID: 12618501.

17. Davidoff AJ, Tang M, Seal B, Edelman MJ. Chemotherapy and survival benefit in elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010; 28:2191–2197. PMID: 20351329.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download