Abstract

Purpose

The retrospective study was performed to assess the efficacy and toxicity profiles of sunitinib in Korean patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC).

Materials and Methods

Between January 2005 and December 2008, 76 Korean patients with recurrent/metastatic RCC who received sunitinib were retrospectively reviewed. The primary end point was progression-free survival and the secondary end points were overall survival and response rate. We also assessed the toxicities associated with sunitinib treatment.

Results

Of the 76 patients, 69 (90.1%) were diagnosed with clear cell RCC. The median progression-free survival and overall survival were 7.2 and 22.8 months, respectively in overall patients. Sixty-two patients (81.6%) received 50 mg 4 week and 2 week off schedule, and 14 patients (18.4%) received 37.5 mg daily on a daily continuous schedule. The objective response rate and disease control rate were 27.6% and 84.2%, respectively. A dose reduction or reduction in dose due to adverse events occurred in 76% of the patients, whereas 11% of the patients had discontinued treatment. Other common laboratory abnormalities were increased serum creatinine (75.6%), elevated alanine aminotransferase (71.0%), neutropenia (61.8%), anemia (69.7%), and increased aspartate aminotrasferase (53.3%). Grade 3/4 toxicities occurred as follows: thrombocytopenia (38.2%), fatigue (10.5%), stomatitis (10.5%), and hand-foot syndrome (9.2%).

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) represents 2~3% of all tumors with an incidence which is increasing annually (1). Up to 30% of RCC patients present in an advanced state, and approximately 40% of patients who undergo curative surgical resection experience recurrence during the follow-up (2,3). Though cytokine treatment with interleukin-2 or interferon-alpha has been widely used as a first-line treatment of metastatic RCC, it has shown a modest survival benefit and a poor quality of life (4). Therefore, alternative agents with greater efficacy and less toxicity are needed for the systemic treatment of renal cell carcinoma. Remarkable improvement in understanding the biology and genetics of RCC has facilitated the novel target-based approaches for the treatment of metastatic RCC.

Sunitinib is an orally available, multi-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor which specifically interferes with platelet-derived growth factor receptor and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (5). These receptor tyrosine kinases are known to play important roles in the pathogenesis of RCC (6,7). In phase III trials, this agent was shown to significantly improve the median progression-free survival (PFS), and yield a higher response rate (RR), and afford a better quality of life over interferon-alfa (8). However, these studies were performed mainly in Western populations. Therefore, further studies about the efficacy and safety profiles are needed for involving Asian RCC treated with sunitinib.

We retrospectively performed this descriptive study to assess the efficacy and toxicity profiles of sunitinib to determine whether there is a difference in Korean patients with metastatic RCC compared to Western patients.

The medical records of RCC patients with recurrent or metastatic disease who had received sunitinib treatment at the Yonsei University Health System (YUHS) between January 2005 and December 2008 were retrospectively reviewed. The inclusion criteria were as follows; Asian ethnicity, metastatic RCC treated with sunitinib, and patients with available medical data for evaluating efficacy and toxicity. Clinicopathologic factors such as age, gender, tumor histology, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS), the number of prior treatments, sites of metastasis, laboratory findings, and patient survival were collected retrospectively and analyzed. We also assessed the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) risk scoring system according to a previous study (9).

Sunitinib was prescribed as a part of clinical or non-clinical trials with 2 different schedules: group 1, 50 mg orally once daily for 4 weeks followed by a 2 week rest period (50 mg 4 weeks on - 2 weeks off schedule); and group 2, 37.5 mg daily continuous dosing. For the evaluation of the response, Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) was applied (10). Regular physical examinations and computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging were performed for treatment outcome every 6~8 weeks. Toxicity was evaluated during the sunitinib treatment according to the National Cancer Institute common toxicity criteria (version 3.0).

Survival analysis was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 15.0. PFS was defined from the date of the 1st dose of sunitinib to the death of any cause or disease progression. Overall survival (OS) was defined from the date of the 1st dose of sunitinib to the death of any cause. We also analyzed the 1-year PFS rate and OS rates. Toxicities were estimated as simple proportions.

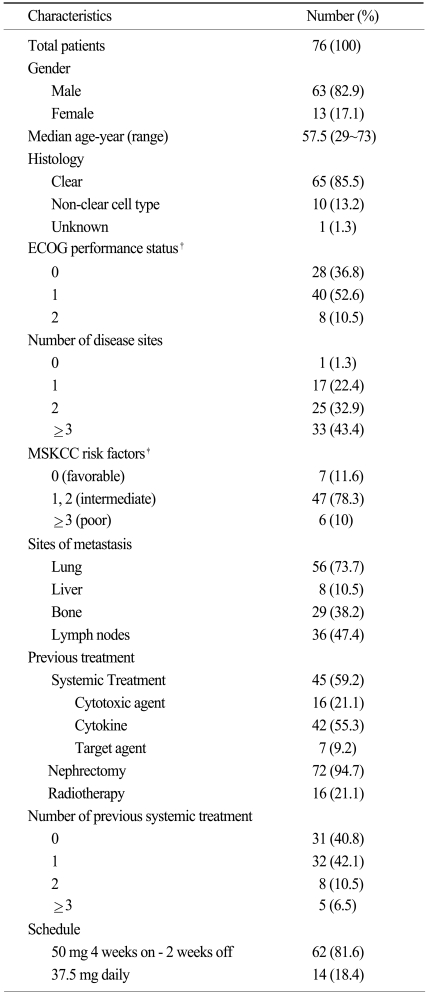

Seventy-six RCC patients were included in the analysis (Table 1). The median age was 57.5 years (range 29~73 years), and the patients consisted of 63 males (82.9%) and 13 females (17.1%). Sixty-five patients (85.5%) were diagnosed with clear cell RCC and the others diagnosed with papillary (n=4), chromophobe (n=2), and mixed cell types (n=4; 2 patients with clear cell combined with papillary cell, 1 patient with clear cell combined with granular cell, and 1 patient with sarcomatoid type combined with clear cell). The distribution of MSKCC scores of 60 patients with evaluable data were as follows: favorable for 7 patients (11.6%), intermediate for 47 patients (78.3%), and poor for 6 patients (10%). The previous treatments were as follows: previous nephrectomy in 72 patients (94.7%), conventional chemotherapy in 16 patients (21.1%), cytokine treatment in 42 patients (55.3%), targeted agent in 7 patients (9.2%), and radiotherapy in 16 patients (21.1%). The number of patients who underwent nephrectomy as a curative aim was 35 (46.1%) and pathologic staging in completely resected patients was as follows: stage I for 6 (24.0%), stage II for 8 (32.0%), stage III for 9 (36.0%), and stage IV for 2 (8.0%) with available pathologic data (25 patients). The metastatectomy was performed in 4 patients and it included lung segmentectomy, retroperitoneal lymphadenocetomy, colon resection and splenectomy with distal pancreatectomy. 5 patients were treated with sorafenib and two with erlotinib/ bevacizumab before sunitinib treatment. Number of disease sites was as follows: 0 for 1 patient (1.3%), 1 for 17 patients (22.4%), 2 for 25 patients (32.9%), and >2 for 34 patients (43.4%), respectively. Most prevalent site of metastasis were the lung (56 patients [73.7%]) followed by the lymph nodes (36 patients [47.4%]), bone (29 patients [38.2%]), and liver (8 patients [10.5%]).

Two different settings in the treatment schedule existed. The majority of the patient (n=62 [81.6%]) received the standard regimen of 50 mg 4 weeks on - 2 weeks off schedule, and 14 patients (18.4%) received the 37.5 mg daily schedule. The number of the patients who received sunitinib as a first-line systemic treatment were 31 (40.8%). After a median of 16.0 months (range, 0.5~40.1 months) of follow-up, 34 patients (44.7%) remained alive with diseases. The median treatment duration was 7.2 months (range, 0.5~35.7 months), and treatment is ongoing in 10 patients (13.2%). The reasons for treatment discontinuation were progressive disease (n=54 [81.8%]), and adverse events (n=7 [10.6%]). Other reasons of dose discontinuation included withdrawal of consent (4 patients) and loss to follow-up.

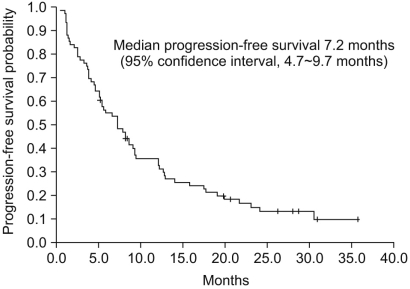

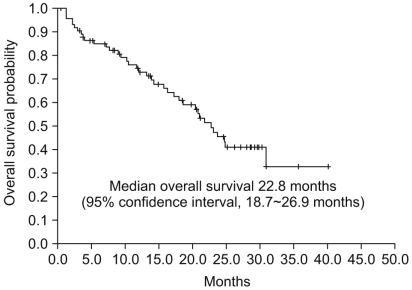

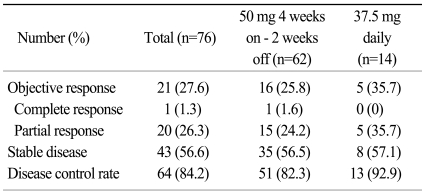

The median PFS was 7.2 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.7~9.7 months, Fig. 1), and the median OS was 22.8 months (95% CI, 18.7~26.9 months, Fig. 2). The 1-year PFS rate and 1-year OS rate were 36.8% (95% CI, 26.1~48.7%) and 61.8% (95% CI, 50.0~72.6%), respectively. Of the 786 evaluable patients, objective RR (including complete and partial responses) was 27.6% (95% CI, 18.0~39.1%) and the disease control rate (including complete response, partial response, and stable disease) was 84.2% (95% CI, 74.0~91.6%), as shown in Table 2. In 10 non-clear cell type RCC patients, 1 patient had a partial response (10%) and disease control was achieved in 8 patients. The median PFS was 5.1 months (95% CI, 4.2~6.0 months) and the median OS was 9.0 months (95% CI, 0.5~17.4 months) in the non-clear cell patients. In addition, in the subgroup who had prior targeted agent treatment (7 patients), 6 patients reached stable disease with 1.5 months (95% CI 0.0~6.7 months) of the median PFS and 12.0 months (95% CI, 1.4~22.5 months) of the median OS. We also evaluated the difference between dosing schedule. The response rate was 25.8% and the disease control rate was 82.3% in the 50 mg 4 weeks on - 2 weeks off dosing schedule, as compared with 35.7% and 92.9%, respectively, in the 37.5 mg daily treatment schedules (Table 2). The median PFS in both the standard and other dosing schedules was 7.2 months.

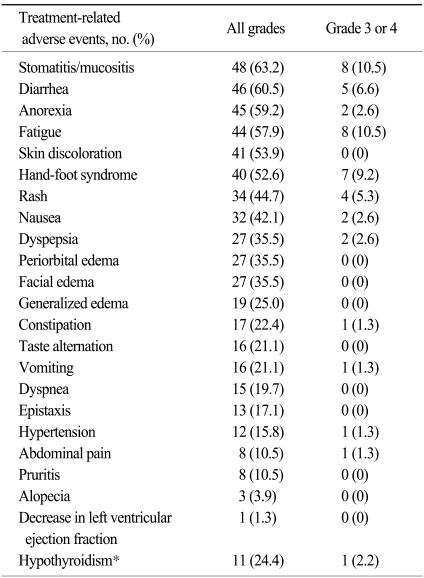

A total 76% of the patients had a dose interruption or dose reduction due to adverse events, whereas only 11% of patients discontinued treatment due to toxicity. Stomatitis and diarrhea were the most commonly reported treatment-related adverse events (63.2% and 60.5%, respectively), but the rate of severe cases with grade 3 or more was not prevalent (10.5% and 6.6%, respectively), as shown in Table 3. Adverse events which were reported with a > 50% frequency were fatigue (57.9%), anorexia (59.2%) and hand-foot syndrome (52.6%). A decrease in the left ventricular ejection fraction of grade 1 was reported in only 1 case, and was without clinical significance. Thyroid function tests were conducted in 45 patients. Eleven cases (24.4%) of hypothyroidism were noted, and 8 (17.8%) patients needed thyroid hormone replacement. In addition, we did not observev hemolytic uremic syndrome or thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura in this group of patients (11).

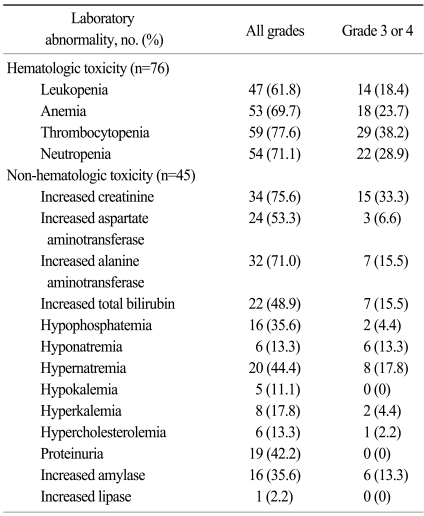

The most common laboratory abnormality was thrombocytopenia (77.6%), and 38.2% of the patients experienced grade 3 or 4 thrombocytopenia, which was no clinical significance (such as bleeding; Table 4). Other common laboratory abnormalities were increased serum creatinine (75.6%), elevated alanine aminotransferase (71%), neutropenia (71.1%), anemia (69.7%), and increased aspartate aminotrasferase (53.3%). Grade 3 or 4 hyperamlyasemia was reported in 13.3% of patients, but no signs of clinical pancreatitis were observed.

RCC is one of the malignancies with a dismal prognosis because of the modest response to conventional chemotherapeutic agents and cytokine therapy. With the elucidation of the molecular pathogenesis of RCC, sunitinib, one of the molecular targeted agents was introduced for the treatment of metastatic RCC (8,12). Previous studies have confirmed the promising efficacy of sunitinib as a standard first-line treatment for metastatic clear cell RCC (8,12). However, these studies were mainly performed for patients in Western countries. Only one small study was reported for Asian patients with RCC who were treated with sunitinib (13), thereby the potential ethnic difference in the efficacy and toxicity of sunitinib have not been established. This retrospective study showed that homogeneous Asian patients with metastatic or recurrent RCC who received sunitinib had comparable survival outcome with patients in previous randomized studies.

For the treatment outcome, the median PFS and OS were 7.2 and 22.8 months, respectively. We also showed a 27.6% objective response rate and an 84.2% disease control rate in this analysis. Previous global trials have demonstrated 8.3 and 11 months of the median PFS and objective response rate of 34% and 31% (8,12). Even though it is difficult to compare this retrospective study with previous phase III randomized trials, we observed that metastatic RCC patients in our study also benefitted from sunitinib treatment. Interestingly, in our study, more patients with poor prognostic factors were included. In terms of MSKCC risk group, 88.3% of patients were in the intermediate or poor groups in this study. In addition, unlike the reported randomized studies, >50% of patients had an ECOG PS 1, and 8 (10.5%) patients with an ECOG PS 2 were also included. Therefore, considering the selection bias of randomized controlled trials which includes relatively better performance status, this finding may reflect more reliable results in real clinical practice with possible benefit from sunitinib treatment for metastatic RCC patients.

In terms of non-hematologic toxicity profiles, stomatitis was the most frequent adverse event in our study, which accounted for 63.2% of the cases; however grade 3 or 4 stomatitis accounted for 10.5% and was manageable. Meanwhile, more stomatitis and hand-foot syndrome were noticed in our study compared to the global trials. For hand-foot syndrome, a much higher rate of all grades and grade 3/4 toxicities (52.6% of all grades, 9.2% of grade 3 or 4) were noted in contrast to the previous trials (15~20% of all grades; 1~7% of grade 3 or 4). Similarly, for stomatitis, a much higher toxicity (63.2% of all grades; 10.5% of grade 3/4) was noted than in previous trials (13~25 % of all grades; 1~5 % of grade 3 or 4).

Hematologic toxicity, especially for thrombocytopenia, was more remarkable in this study. All grades of thrombocytopenia were 77.6%, and it was similar with Western data (8,12). However, patients in the present study experienced a much higher rate of grade 3 or 4 thrombocytopenia (38.2% in YUHS data versus 8% in the randomized phase III trial, respectively). In addition, thrombocytopenia was the most common cause of dose reduction, delay, and discontinuation in our study. Other grade 3 or 4 hematologic toxicities such as neutropenia (28.9%), anemia (23.7%), and leukopenia (18.4%) were also more frequent than in Western analyses. This finding was consistent with Japanese study involving sunitinib treatment (13). Whether this toxicity is directly related to host factors such as poor PS, or prior numbers of treatments remains uncertain. A disparity in the toxicity profiles between Eastern and Western countries has been in colon cancer patients who received capecitabine (14-16). Compared to Caucasians, a higher incidence of hand-foot syndrome and a lower rate of diarrhea occurred in non-Caucasian patients treated with capecitabine, suggesting an ethnic difference between Western and Eastern patients. As shown in patients receiving capecitabine treatment, this finding may be caused by ethnic differences. Therefore, these descriptive results should be interpreted cautiously and further study with a larger sample size and pharmacokinetic tests are needed to clarify this finding.

The current single center retrospective analysis had several limitations. The patients in this retrospective study consisted of a heterogenous population. Thirteen percent of the patients had non-clear cell RCC, and 9% of all patients had already received targeted agents before sunitinib.

Nevertheless, this study represents one of the few studies in which sunitinib treatment was evaluated for efficacy and toxicity in Asian patients with RCC. Our results indicated that sunitinib treatment was effective and tolerable in Korean patients with metastatic RCC. Further studies with biochemical data would further clarify the clinical significance of theses findings.

This study assessed sunitinib treatment for recurrent/metastatic Korean patients with RCC in terms of efficacy and toxicity. PFS, OS, and RR in Korean patients was compatible to Western patients, although some toxicities in Korean patients were more frequent and severe, but were manageable.

References

1. Kamangar F, Dores GM, Anderson WF. Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents: defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. J Clin Oncol. 2006; 24:2137–2150. PMID: 16682732.

2. Jemal A, Murray T, Ward E, Samuels A, Tiwari R, Ghafoor A, et al. Cancer statistics, 2005. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005; 55:10–30. PMID: 15661684.

3. Janzen NK, Kim HL, Figlin RA, Belldegrun AS. Surveillance after radical or partial nephrectomy for localized renal cell carcinoma and management of recurrent disease. Urol Clin North Am. 2003; 30:843–852. PMID: 14680319.

4. Chow LQ, Eckhardt SG. Sunitinib: from rational design to clinical efficacy. J Clin Oncol. 2007; 25:884–896. PMID: 17327610.

5. Abrams TJ, Lee LB, Murray LJ, Pryer NK, Cherrington JM. SU11248 Inhibits KIT and platelet-derived growth factor receptor β, in preclinical models of human small cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003; 2:471–478. PMID: 12748309.

6. Gnarra JR, Tory K, Weng Y, Schmidt L, Wei MH, Li H, et al. Mutations of the VHL tumour suppressor gene in renal carcinoma. Nat Genet. 1994; 7:85–90. PMID: 7915601.

7. Iliopoulos O, Levy AP, Jiang C, Kaelin WG Jr, Goldberg MA. Negative regulation of hypoxia-inducible genes by the von Hippel-Lindau protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996; 93:10595–10599. PMID: 8855223.

8. Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, Michaelson MD, Bukowski RM, Rixe O, et al. Sunitinib versus interferon α in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007; 356:115–124. PMID: 17215529.

9. Motzer RJ, Bacik J, Schwartz LH, Reuter V, Russo P, Marion S, et al. Prognostic factors for survival in previously treated patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004; 22:454–463. PMID: 14752067.

10. Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000; 92:205–216. PMID: 10655437.

11. Choi MK, Hong JY, Jang JH, Lim HY. TTP-HUS associated with sunitinib. Cancer Res Treat. 2008; 40:211–213. PMID: 19688133.

12. Motzer RJ, Rini BI, Bukowski RM, Curti BD, George DJ, Hudes GR, et al. Sunitinib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. JAMA. 2006; 295:2516–2524. PMID: 16757724.

13. Uemura H, Shinohara N, Naito S, Akaza H. A phase II study of the efficacy and safety of sunitinib in treatment-naive and pretreated Japanese patients (pts) with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC). J Clin Oncol. 2008; 26:15S. (Abstr 16108).

14. Law CC, Fu YT, Chau KK, Choy TS, So PF, Wong KH. Toxicity profile and efficacy of oral capecitabine as adjuvant chemotherapy for Chinese patients with stage III colon cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007; 50:2180–2187. PMID: 17963003.

15. Yen-Revollo JL, Goldberg RM, McLeod HL. Can inhibiting dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase limit hand-foot syndrome caused by fluoropyrimidines? Clin Cancer Res. 2008; 14:8–13. PMID: 18172246.

16. Saif MW, Sandoval A. Atypical hand-and-foot syndrome in an African American patient treated with capecitabine with normal DPD activity: Is there an ethnic disparity? Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2008; 27:311–315. PMID: 19037763.

Table 1

Patient characteristics

*Data of cell type in one patient was missing. †Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, ‡Risk factors in Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) risk scoring system are a low hemoglobin level, an elevated corrected calcium level, an elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase level, a poor performance status and an interval of less than 1 year between diagnosis and treatment. The MSKCC risk factors could not be calculated in 20 patients due to incomplete data.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download