Introduction

Pancreatic cancer was Korea's fifth leading cause of cancer-related deaths in 2006 and almost all the pancreatic cancer patients were expected to die from the disease (

1). The development of better imaging techniques has allowed more pancreatic tumors to be recognized and diagnosed. Pancreatic neoplasms and malignancies arise from both the endocrine and exocrine portions of the organ. More than 90% of the malignant tumors of the pancreas arise from the exocrine elements of the gland (ductal and acinar cells), and these tumors demonstrate features that are consistent with adenocarcinoma. The World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes several histomorphologic variants of ductal adenocarcinoma, including mucinous noncystic carcinoma, signet ring carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma, undifferentiated (anaplastic) carcinoma, undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells and mixed ductal-endocrine carcinoma. The WHO currently recognizes clear cell carcinoma as a "miscellaneous" carcinoma of the pancreas, and this tumor is characteristically rich in glycogen and poor in mucin (

2). Unfortunately, not much data is available on this clear cell tumor. The incidence and prognosis are not well known and only a few such cases have been reported in the literature. Moreover, there has been no previous report of primary clear cell carcinoma of the pancreas in Korea. Herein, we report on a unique case of primary clear cell carcinoma of the pancreas and we include the pathologic description of this tumor.

Go to :

Discussion

Clear cell carcinoma is a common variant of carcinoma of kidney, ovary, thyroid and lung (

3,

4), but this tumor rarely originates from the pancreas. Only several cases of clear cell carcinoma have been reported throughout the world (

Table 1). In addition, there has been only one Korean case report of clear cell islet cell tumor of the pancreas at 1997 (

5). However, there has been no previous report of primary clear cell ductal carcinoma of the pancreas in Korea.

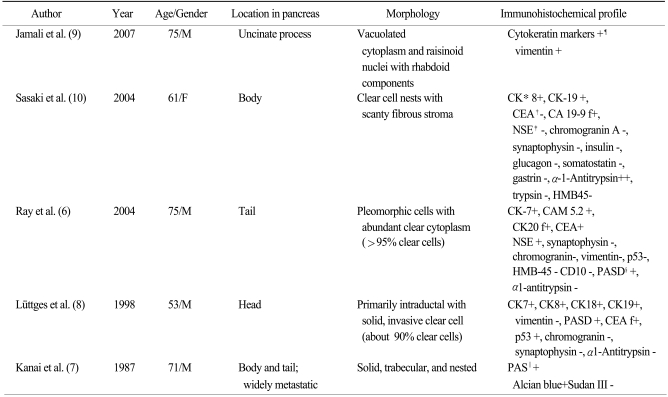

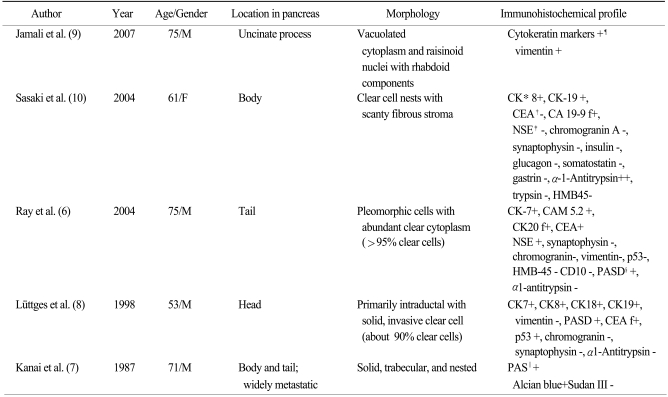

Table 1

The previously reported examples of pancreatic clear cell carcinoma

The incidence and prognosis of this tumor are not well known and the systematic overview of this disease entity is insufficient. The clinical characteristics and prognosis were diverse in several case reports (

6-

10). In one study, the clinical characteristics and survival data of 20 cases of pancreatic carcinoma that showed clear cell features were not significantly different from that of the cases of conventional ductal cell carcinoma (

11).

Ray et al. (

6) have summarized seven cases in which this morphology was described. Of those cases that underwent histochemical characterization, there was scanty, focal or strong positivity for mucin. Yet Kim et al. (

11) recently reported that 20 (24%) pancreatic adenocarcinomas were identified with clear cell features, including 12 clear cell carcinomas and 8 ductal adenocarcinomas with a clear cell component (defined as less than 75% of the tumor with clear cells) of the 84 pancreatic adenocarcinomas. In addition, they suggested that HNF1B was a useful biomarker to identify clear cell carcinomas. The survival analysis, as stratified by the degree of HNF1B staining without regard to the morphologic subtype, showed significantly decreased survival with high HNF1B staining (p<0.01). However, they included a mixture of both the usual ductal cell phenotype and the clear cell phenotype. As a result, 12 of 84 cases that had been diagnosed as primarily adenocarcinoma of the ductal type were found to have a significant (at least 75%) involvement by a clear cell component.

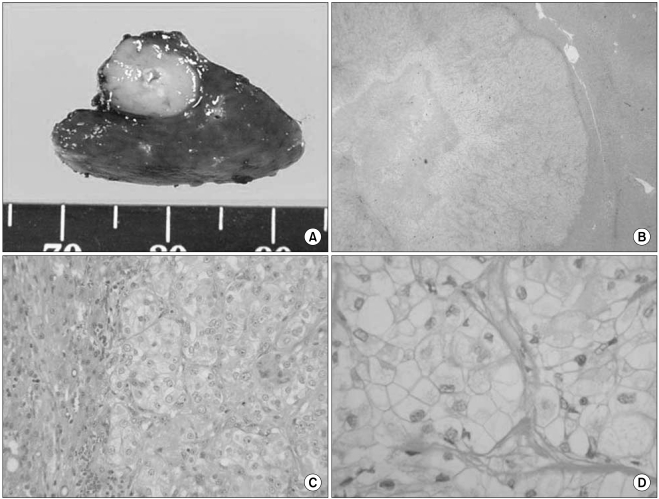

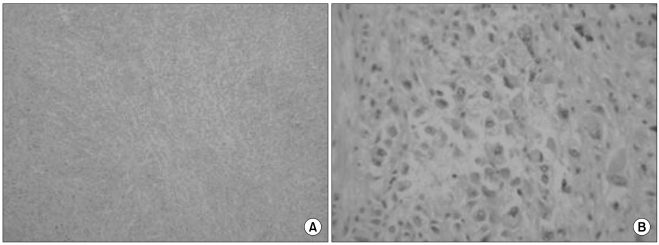

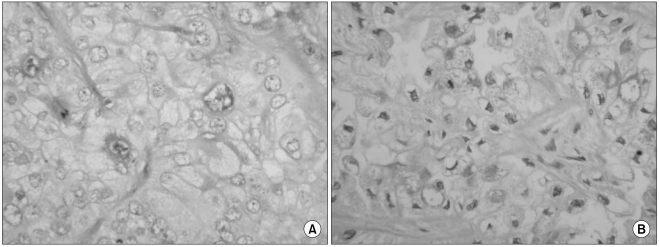

The histologic features of clear cell carcinoma of the pancreas have varied in the previous reports. Kanai et al. (

7) first reported on a case of clear cell carcinoma and the tumor was predominantly composed of a clear cell component. The tumor in that case had a small amount of extracellular mucin formation and the neoplastic cells seemed to have scant intercellular adhesiveness; this histologic configuration appears to be similar to that of signet-ring cell carcinoma. The tumor in the case of Lüttges et al. (

8) was predominantly composed of a clear cell component and it had one area of a papillotubular component. Jamali et al. (

9) reported a case of adenosquamous carcinoma of the pancreas with both clear cell and rhabdoid components, and this was similar to our case. Rhabdoid cells have been recognized in a wide range of epithelial and mesenchymal tumors. The rhabdoid phenotype is characterized by a large round to polygonal cell with eccentric nuclei, prominent nucleoli and abundant deeply acidophilic/eosinophilic, dot-like, hyaline filamentous cytoplasmic inclusions. The rhabdoid phenotype represents a common clonal dedifferentiated end point in malignant tumors of varying histogenesis (

12). It has been recently suggested that rhabdoid changes may be a type of degeneration or a preliminary stage before apoptosis or cell necrosis (

13).

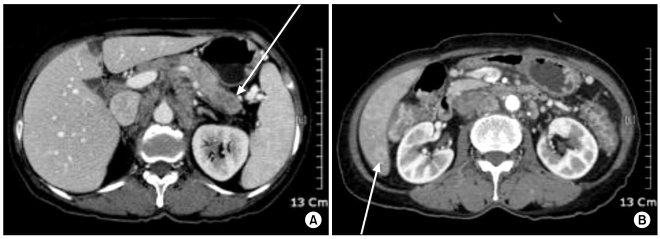

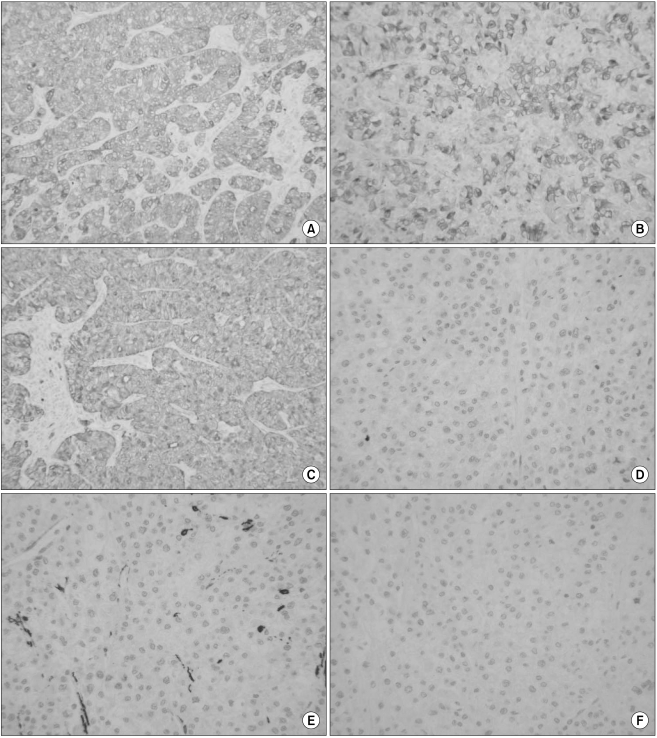

The differential diagnosis of clear cell lesions in the pancreas includes pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (sugar tumor) and metastatic carcinomas. The possibility of pancreatic endocrine tumors is excluded by the absence of neuroendocrine markers such as synaptophysin and chromogranin in the neoplastic cells. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor occurs only rarely in the pancreas; it has a solid growth pattern and it is immunohistochemically characterized by positivity for HMB-45, which was negative in our case. For our case, the possibility of metastasis to the pancreas was taken into account. Metastasis into the pancreas has been described for various tumors, including renal cell carcinoma, breast carcinoma, colon carcinoma, malignant melanoma and sarcoma. However, our clinical investigation failed to detect any extra-pancreatic primary tumors in our case. Moreover, the immunohistochemical findings could exclude metastatic renal clear cell carcinoma or malignant melanoma. We diagnosed our case as primary pancreatic cancer based on the pancreatic and liver masses and the elevated serum level of CA 19-9.

The immunohistochemical findings of primary clear cell carcinoma are currently unclear (

Table 1). Genetic analysis has recently been performed on pancreatic carcinomas. The K-ras oncogene is a major targeting gene because more than 80% of pancreatic carcinomas of a ductal origin have been reported to have a mutation in the K-ras oncogene (

14). Mutation of the K-ras oncogene is rare in the neoplasms of a nonductal origin, so the presence of a mutation of the K-ras oncogene is generally presumed to indicate a tumor's duct cell origin. As for clear cell carcinoma, Lüttges et al. (

8) detected a mutation at codon 12 in the K-ras oncogene and they reported that their clear cell carcinoma was of a duct cell origin. Yet in the case of Sasaki et al. (

10), any mutation of the K-ras oncogene was not detected.

In summary, we have presented a rare case of clear cell carcinoma of the pancreas with a review of the related literature. The specific criteria to confirm this tumor have not yet been established. Kim L et al. (

6), Lüttges J et al. (

8) and Ray S et al. (

6) classified clear cell carcinoma as those tumors with more than 75%, 90% and 95%, respectively, of the tumor cells being clear cells. To define this disease entity, further investigation with other methods such as biomarker studies, gene analysis and immunohistochemistry are needed to differentiate clear cell carcinoma of the pancreas from other pancreatic tumors.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download