Abstract

Purpose

Anthracycline and taxanes are effective agents in advanced breast cancer and prolong survival times. Some patients achieve prolongation of life with capecitabine, gemcitabine, or vinorelbine, even after failure of both anthracycline and taxanes. We analyzed the efficacy and toxicity of gemcitabine and vinorelbine combination chemotherapy in anthracycline- and taxane-pretreated advanced breast cancer.

Materials and Methods

The medical records of anthracycline- and taxane-pretreated metastatic breast cancer patients who received gemcitabine and vinorelbine combination chemotherapy at the Seoul National University Hospital were reviewed. Gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2) and vinorelbine (25 mg/m2) were administered intravenously on days 1 and 8 every 3 weeks.

Results

Between 2000 and 2006, 57 patients were eligible (median age, 45 years), and the median number of previous chemotherapy regimens was 3 (range, 1~5). The overall response rate was 30% (95% CI, 18.1~41.9), and the disease control rate was 46% (PR, 30%; SD, 16%). The median duration of follow-up was 33.4 months, the median time-to-progression (TTP) was 3.9 months, and the median overall survival was 10.8 months. None of thepatients with patients with anthracycline and taxane primary resistance showed a response and the median TTP for these patients was significantly shorter than that of other patients (1.9 vs. 4.4 months; p=0.018). Although the efficacy was unsatisfactory in patients with both anthracycline and taxane primary resistance, gemcitabine and vinorelbine combination chemotherapy showed comparable efficacy in anthracycline- and/or taxane-sensitive patients and the patients with secondary resistance, even after failure of second-line therapy. Grade 3/4 hematologic toxicities included neutropenia (18.1%) and febrile neutropenia (0.3%), and non-hematologic toxicities were tolerable.

The incidence of breast cancer has increased in Korea during the last 20 years (1). Despite advances in metastatic breast cancer treatment, the median survival time for patients with breast cancer has been estimated to be about 2 years, and achieving a cure is rare (2). Anthracycline- and taxane-containing regimens have been established as the most effective chemotherapeutic agents for first- and second-line therapies in metastatic breast cancer with respect to a prolongation of survival time (3). However, earlier use of these agents as adjuvant/neoadjuvant chemotherapy resulted in anthracycline and taxane resistance, making further options a concern.

Gemcitabine is a nucleoside anti-metabolite and has proven anti-tumor activity in breast, pancreatic, non-small cell lung, bladder, and ovarian cancers (4). In an UK/German phase II trial, gemcitabine (800 mg/m2) was administered on days 1, 8, and 15 of a 28-day cycle to patients with advanced breast cancer who had received no more than one regimen given in an adjuvant or metastatic setting. This trial produced an overall response rate of 25% and a median survival duration of 11.5 months (5).

Vinorelbine is a semi-synthetic vinca alkaloid with broad anti-tumor activity that inhibits microtubule polymerization and has a lower neurologic toxicity (6). As single agent therapy, vinorelbine is tolerable in advanced breast cancer, and in a phase II trial in the US, the response rate was 32% as a second-line treatment and the median survival duration was 15.5 months (7).

As reported by Herbst et al (8) in preclinical data involving patients with recurrent advanced lung cancer, gemcitabine and vinorelbine showed an additive effect, and the efficacy in patients with metastatic breast cancer after less than two chemotherapy regimens was demonstrated in a phase II trial (9-12). Since 2000, we have treated heavily pretreated patients who failed both anthracycline and taxanes, as first and/or second line therapies, with gemcitabine and vinorelbine. The median duration of follow-up has been 33.4 months and we present our data herein.

We reviewed the medical records of patients with metastatic breast cancer who received gemcitabine and vinorelbine chemotherapy following anthracycline and taxane treatment at the Seoul National University Hospital between 2000 and 2006. Eligibility criteria included: 1) histologically- and cytologically-documented breast cancer; 2) prior anthracycline and taxane treatment for adjuvant, neoadjuvant, or palliative chemotherapy; 3) at least one measurable lesion; 4) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0~2; 5) adequate hematologic, hepatic, and renal function; and 6) salvage treatment with gemcitabine and vinorelbine.

Primary resistance was defined as progressive disease during or within 6 months after completion of anthracycline and taxanes in an adjuvant setting, and with no documented tumor response to anthracycline and taxanes in a metastatic setting. Secondary resistance was defined as disease progression after a documented clinical response during chemotherapy or 6 months after completion of anthracycline and taxanes for metastatic disease.

All patients received a 3-week treatment schedule of gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2 in a 30 minute intravenous infusion) plus vinorelbine (25 mg/m2 in a 10 minute intravenous infusion) on days 1 and 8. Dosage modification for hematologic toxicities was based on the hematologic test results obtained on the day of treatment before dosing. Chemotherapy was interrupted until resolved to grade 1 if the grade of hematologic toxicity was ≥2. In case of grade 2 hematologic toxicity, chemotherapy was not adjusted for the next cycle, but in grades 3 or 4 hematologic toxicities, a 25% dose reduction of gemcitabine and vinorelbine was instituted for the next cycle.

The primary end point of the current study was response rate (RR); the secondary end points were time-to-progression (TTP), overall survival (OS), toxicities, and prognostic factor analysis. TTP and OS were calculated from the first day of gemcitabine/vinorelbine chemotherapy. Patients with measurable disease were assessed with a complete medical history, physical examination, and laboratory studies every cycle, and imaging studies were checked every 2 cycles according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) criteria (13). Toxicities were graded by the National Cancer Institute of Common Toxicity Criteria, version 3.0 (14).

Between 2000 and 2006, 62 anthracycline- and taxane-pretreated patients received gemcitabine and vinorelbine combination chemotherapy. Of the 62 patients, 57 patients were eligible with a median age of 45 years (range, 25~67 years). Five patients were excluded from analysis because three patients received insufficient therapy, defined as less than two and two patients were lost to follow-up after two cycles without a response evaluation.

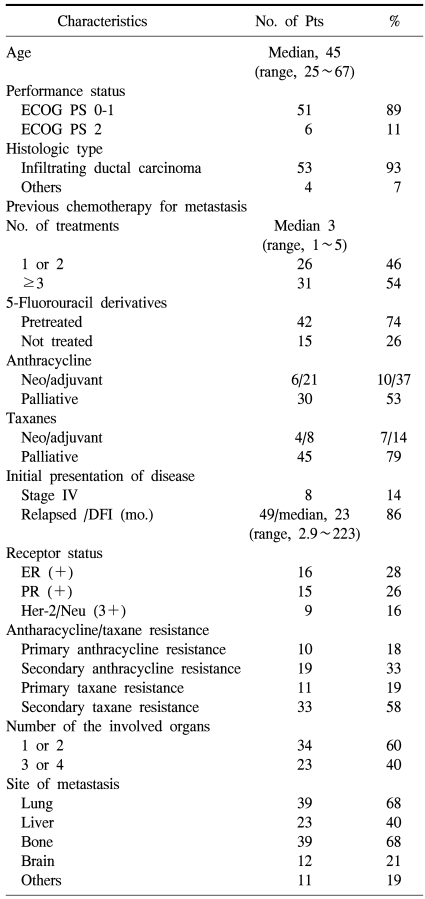

The patient characteristics are listed in Table 1. Eight patients (14%) initially had stage IV disease and 49 patients (86%) had relapsed breast cancer with a median disease-free interval of 23 months (range, 2.9~223 months) after curative surgery. Most patients had visceral disease with lung (68%), liver (40%), and brain (21%) involvement. Estrogen receptor (ER) was positive in 16 patients (28%) and HER-2 was positive in 9 patients (16%) by immunohistochemistry. Thirty-one patients (54%) received ≥3 prior chemotherapy regimens for metastatic disease. All patients received anthracycline and taxanes previously. Thirty patients (53%) received an anthracycline as palliative first- or second-line therapy for metastatic disease and 7 of 30 patients (23%) had primary resistance to anthracycline. Twenty-seven (47%) patients received adequate anthracycline (≥300 mg/m2 of doxorubicin) in a neoadjuvant or adjuvant setting and these patients did not receive an anthracycline in a palliative setting because of a cumulative dose limitation. Three of 27 patients (11%) belonged to anthracycline primary resistance who relapsed within 6 months after completion of neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy. Forty-five patients (79%) treated with taxane as palliative first- or second-line therapy for metastatic disease and 11 of 45 patients (24%) had primary resistance to taxane. Twelve patients (21%) were exposed to taxanes during neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy. Four patients (7%) had primary resistance to both anthracyclines and taxanes. Furthermore, most patients (74%) had already been exposed to 5-fluouracil derivatives during previous treatment.

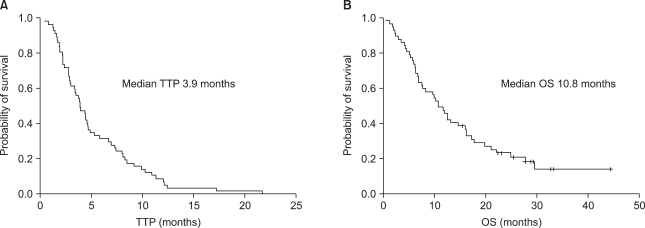

Of 57 patients who were evaluable, 17 patients (30%) had a partial response (PR) and 9 patients (16%) had stable disease (SD). The overall RR was 30% (95% CI, 18.1~41.9%) and the disease control rate was 46%. At a median duration of follow-up of 33.4 months, the median TTP and OS were 3.9 and 10.8 months, respectively (Fig. 1).

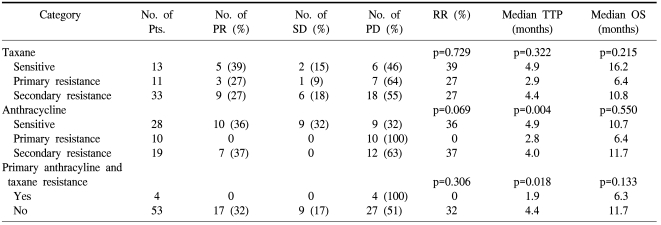

Table 2 lists the RR and TTP after gemcitabine/vinorelbine according to the anthracycline and taxane resistance category. The patients with anthracycline sensitivity, taxane sensitivity, or secondary resistance tended to show higher RR, although there was no statistical significance. However, there was no response in patients with both taxane and anthracycline resistance. The median TTP for patients with anthracycline and taxane primary resistance was significantly shorter than that of other patients (1.9 vs. 4.4 months; p=0.018). The median OS in the anthracycline and taxane primary resistance category was shorter than other patients, but there was no statistical significance (6.3 vs. 11.7 months; p=0.133). Gemcitabine and vinorelbine showed comparable efficacy in anthracycline- and/or taxane-sensitive patients and patients with secondary resistance, even after failure of second-line therapy. The RR was not different according to the number of previous treatment regimens for metastatic disease (34.6% for 1 or 2 vs. 25.8% for 3 or more, p=0.566). The TTP and OS in the patients who received one or two lines of chemotherapy for metastatic disease were 3.9 and 10.7 months, respectively, and the TTP and OS in the patients who received three or more lines of chemotherapy for metastatic disease were comparable with those who received <3 (3.9 and 10.8 months, respectively).

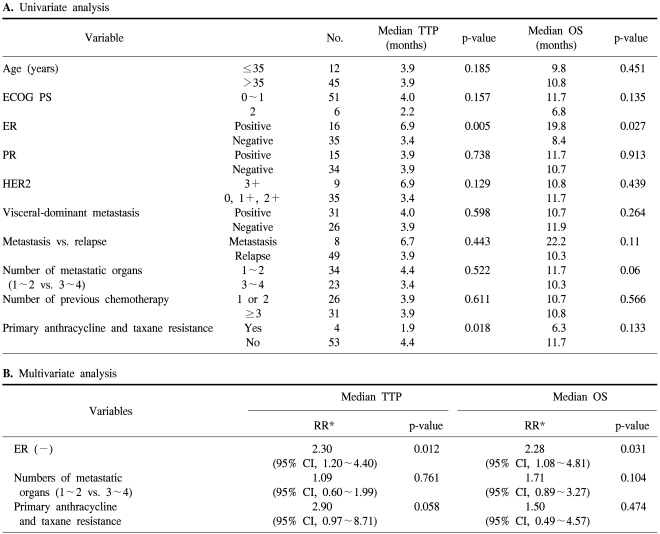

Univariate analysis showed that ER status (p=0.005) and anthracycline and taxane primary resistance (p=0.018) had a significant impact on TTP, whereas ER status (p=0.027) and the number of metastatic organs (p=0.06) had an impact on OS. In multivariate analysis, patients who were ER-positive showed a prolonged TTP (p=0.012) and OS (p=0.031). Anthracycline and taxane primary resistance tended to shorten the TTP (p=0.058), but did not impact the OS (p=0.474; Table 3)

Our patients received a total of 287 cycles of treatment (median, 3 cycles; range, 2~12 cycles). The planned dose-intensity for gemcitabine and vinorelbine was 666 mg/m2/week and 16.6 mg/m2/week, respectively, and the delivered mean dose-intensity for gemcitabine and vinorelbine was 627.9 mg/m2/week and 15.7 mg/m2/week, respectively. Therefore, the relative dose-intensity of each drug was 94%.

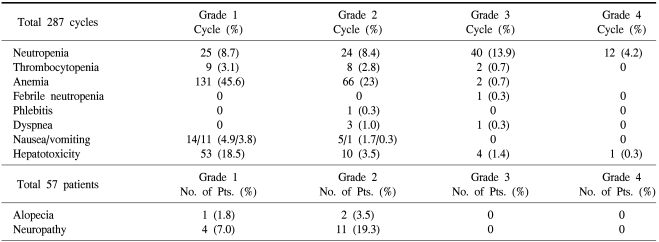

Grade 3/4 hematologic toxicities were neutropenia (18.1%) and febrile neutropenia (0.3%). Non-hematologic toxicities were generally infrequent (Table 4).

Anthracycline- and taxane-containing regimens are increasingly used as preferred first-line therapies in the treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer or adjuvant/neoadjuvant chemotherapy in locoregional breast cancer. However, there is no consensus for therapeutic choice for patients who have failed previous anthracycline- and taxane-containing regimens. Therefore, many studies have attempted to overcome this clinical problem.

Gemcitabine and vinorelbine represent an attractive regimen due to the favorable toxicity profile of the two drugs and the different cellular targets which are DNA for gemcitabine and microtubules for vinorelbine (15,16). A phase II trial (51 patients) of gemcitabine and vinorelbine as second-line treatment in patients with metastatic breast cancer was reported (9). The overall RR was 33.3%, the median TTP was 6.3 months, and the median OS was 17.8 months. These results were superior to our data, but gemcitabine and vinorelbine were administered in 36 patients as second-line treatment and in 15 patients as third-line treatment in this trial. Other studies reported RRs of only 21~24% (10-12). One-half of our patients received gemcitabine and vinorelbine as fourth-line chemotherapy in a metastatic setting and the median number of previous chemotherapy regimens was three. Interestingly, the TTP and OS in the patients who received ≥3 lines of chemotherapy for metastatic disease was comparable with those of who received <3.

Various definitions of anthracycline and taxane resistance have been used in previous reports. Ravadin et al. (17) defined anthracycline resistance as progression while receiving an anthracycline-containing regimen for metastatic breast cancer. In another report by Valero et al. (18), patients whose disease failed to respond to first- or second-line anthracycline-containing chemotherapy, or who demonstrated recurrence during the administration of adjuvant chemotherapy, were defined as having primary resistance. Secondary resistance was defined as disease progression after objective response to anthracycline-containing chemotherapy. Claire et al. (19) defined disease progression while receiving paclitaxel-based chemotherapy after 4 cycles of paclitaxel-based chemotherapy, or clinical remission followed by relapse within 6 months after completion of paclitaxel-based chemotherapy. In our study, anthracycline and taxane resistance was defined by the clinical definition of the 2000 Cancer Research Campaign (20).

Among patients with primary or secondary anthracycline and taxane resistance, patients with primary anthracycline and taxane resistance had no response compared to patients in other categories. The median TTP in patients with primary anthracycline and taxane resistance was significantly shorter than in other patients (1.9 vs. 4.4 months, p=0.018); however, statistically the median OS was not different (6.3 vs. 11.7 months, p=0.133; Table 2). Although the efficacy was unsatisfactory in patients with primary anthracycline and taxane resistance, gemcitabine and vinorelbine combination chemotherapy showed comparable efficacy in patients with sensitivity and secondary resistance, even after failure of second-line therapy. The important finding of our study is that gemcitabine/vinorelbine combination therapy is a promising option in anthracycline- and taxane-pretreated patients.

Although HER-2 is a poor prognostic factor, HER-2-positive patients tend to have a longer TTP than in other patients (6.9 vs. 3.4 months, p=0.129) in our study, even though there was no statistical significance. Nine patients were HER-2-positive, and of these patients, 6 patients received trastuzumab, confirming that trastuzumab could overcome the poor prognosis associated with HER-2-positive breast cancer (21,22). Three patients received gemcitabine and vinorelbine after failure of trastuzumab, and 2 patients had a PR. This finding can be explained by the efficacy of gemcitabine and vinorelbine combination chemotherapy in trastuzumab-failure patients, and the carryover effect of trastuzumab (23,24). Moreover, 74% of our population was pretreated with 5-fluorouracil derivatives after anthracycline and taxane failure, and our population was exposed to gemcitabine and vinorelbine in later stages of the disease.

ER-positivity is a good prognostic factor for TTP and OS (6.9 vs. 3.4 months, p=0.005; and 19.8 vs. 8.4 months, p=0.027, respectively) in univariate analysis, and is an independent prognostic factor in multivariate analysis (RR, 2.30, p=0.012; and RR, 2.28, p=0.031, respectively; Table 3).

The present combination of gemcitabine and vinorelbine was well-tolerated in metastatic breast cancer patients, even with three or more pretreated chemotherapy regimens. Grades 3 or 4 hematologic toxicities included neutropenia (18.1%), febrile neutropenia (0.3%), thrombocytopenia (0.7%), and anemia (0.7%). Grades 3 or 4 non-hematologic toxicities were generally infrequent.

Our study has demonstrated the efficacy and tolerability of the gemcitabine/vinorelbine combination chemotherapy in anthracycline- and taxane-pretreated metastatic breast cancer, and it also showed the possibility of treatment in heavily pre-treated patients. Moreover, sensitivity categorizing is a useful tool to predict the outcome of patients.

Notes

This study was supported in part by a Korean Research Foundation Grant funded by the Korean Government (MOEHRD, Basic Research Promotion Fund; KRF-2006-531-E00034) and by a grant from the Korean Health 21 R&D Project of the Ministry of Health & Welfare in the Republic of Korea (0412-CR01-0704-0001).

References

1. Ahn SH. Korean Breast Cancer Society. Clinical characteristics of breast cancer patients in Korea in 2000. Arch Surg. 2004; 139:27–30. PMID: 14718270.

2. Winer EP, Morrow M, Osborne CK, Harris JR. Devita VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, editors. Malignant tumors of the breast. Cancer: principles and practice of oncology. 2004. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins;p. 1651–1717.

3. Kataja VV, Colleoni M, Bergh J. ESMO minimum clinical recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of locally recurrent or metastatic breast cancer (MBC). Ann Oncol. 2005; 16:i10–i12. PMID: 15888735.

4. Plunkett W, Huang P, Searcy CE, Gandhi V. Gemcitabine: preclinical pharmacology and mechanisms of action. Semin Oncol. 1996; 23:3–15. PMID: 8893876.

5. Carmichael J, Possinger K, Phillip P, Beykirch M, Kerr H, Walling J, et al. Advanced breast cancer: a phase II trial with gemcitabine. J Clin Oncol. 1995; 13:2731–2736. PMID: 7595731.

6. Potier P. The synthesis of navelbine prototype of a new series of vinblastine derivatives. Semin Oncol. 1989; 16:2–4. PMID: 2540531.

7. Weber BL, Vogel C, Jones S, Harvey H, Hutchins L, Bigley J, et al. Intravenous vinorelbine as first-line and second-line therapy in advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1995; 13:2722–2736. PMID: 7595730.

8. Herbst RS, Lynch C, Vasconcelles M, Teicher BA, Strauss G, Elias A, et al. Gemcitabine and vinorelbine in patients with advanced lung cancer: Preclinical studies and report of a phase I trial. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2001; 48:151–159. PMID: 11561781.

9. Donadio M, Ardine M, Berruti A, Ritorto G, Fea E, Mistrangelo M, et al. Gemcitabine and vinorelbine as second-line treatment in patients with metastatic breast cancer: A phase II study. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2003; 52:147–152. PMID: 12764672.

10. Mariani G, Tagliabue P, Zucchinelli P, Brambilla C, Demicheli R, Villa E, et al. Phase I/II study of gemcitabine in association with vinorelbine for metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2001; 70:163–169. PMID: 11804180.

11. Nicolaides C, Dimopoulos MA, Samantas E, Bafaloukos D, Kalofonos C, Fountzilas G, et al. Gemcitabine and vinorelbine as second-line treatment in patients with metastatic breast cancer progressing after first-line taxane-based chemotherapy: A phase II study conducted by the hellenic cooperative oncology group. Ann Oncol. 2000; 11:873–875. PMID: 10997817.

12. Rossi E, Perrone F, Labonia V, Landi G, Nuzzo F, Amabile G, et al. Is gemcitabine plus vinorelbine active in second-line chemotherapy of metastatic breast cancer? A single-center phase 2 study. Oncology. 2003; 64:479–480. PMID: 12759551.

13. Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000; 92:205–216. PMID: 10655437.

14. Trotti A, Colevas AD, Setser A, Rusch V, Jaques D, Budach V, et al. CTCAE version 3.0: development of a comprehensive grading system for the adverse effects of cancer treatment. Seminars in Radiation Oncology. 2003; 13:176–181. PMID: 12903007.

15. Grindey GB, Hertel LW, Plunkett W. Cytotoxicity and antitumor activity of 2', 2'-difluorodeoxycytidine (Gemcitabine). Cancer Invest. 1990; 8:313. PMID: 2400957.

16. Binet S, Fellous A, Lataste H, Krikorian A, Couzinier JP, Meininger V. In situ analysis of the action of navelbine on various types of microtubules using immunofluorescence. Semin Oncol. 1989; 16:5–8. PMID: 2652320.

17. Ravdin PM, Burris HA 3rd, Cook G, Eisenberg P, Kane M, Bierman WA, et al. Phase II trial of docetaxel in advanced anthracycline-resistant or anthracenedione-resistant breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1995; 13:2879–2885. PMID: 8523050.

18. Valero V, Holmes FA, Walters RS, Theriault RL, Esparza L, Fraschini G, et al. Phase II trial of docetaxel: a new, highly effective antineoplastic agent in the management of patients with anthracycline-resistant metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1995; 13:2886–2894. PMID: 8523051.

19. Verschraegen CF, Sittisomwong T, Kudelka AP, Guedes EP, Steger M, Nelson-Taylor T, et al. Docetaxel for patients with paclitaxel-resistant mullerian carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2000; 18:2733–2789. PMID: 10894873.

20. Pivot X, Asmar L, Buzdar AU, Valero V, Hortobagyi G. A unified definition of clinical anthracycline resistance breast cancer. Brit J Cancer. 2000; 82:529–534. PMID: 10682660.

21. Burris H III, Yardley D, Jones S, Houston G, Broome C, Thompson D, et al. Phase II trial of trastuzumab followed by weekly paclitaxel/carboplatin as first-line treatment for patients with metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004; 22:1621–1629. PMID: 15117984.

22. Tedesco KL, Thor AD, Johnson DH, Shyr Y, Blum KA, Goldstein LJ, et al. Docetaxel combined with trastuzumab is an active regimen in HER-2 3+ overexpressing and fluorescent in situ hybridization-positive metastatic breast cancer: a multi-institutional phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004; 22:1071–1077. PMID: 15020608.

23. O'Shaughnessy JA, Vukelja S, Marsland T, Kimmel G, Ratnam S, Pippen JE. Phase II study of trastuzumab plus gemcitabine in chemotherapy-pretreated patients with metastatic breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2004; 5:142–147. PMID: 15245619.

24. Chan A. A review of the use of trastuzumab (Herceptin) plus vinorelbine in metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2007; 18:1152–1158. PMID: 17264064.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download