Abstract

Purpose

This study was performed to determine the feasibility and safety of the use of induction chemotherapy combined with docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil (TPF) followed by concurrent chemoradiation therapy for locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN).

Materials and Methods

The patients, that were initially not treated for locally advanced SCCHN, underwent three cycles of induction chemotherapy every 3 weeks at a dose of 70 mg/m2 docetaxel D1, 75 mg/m2 cisplatin D1, 1000 mg/m2 5-FU D1-4, and subsequently received concurrent chemoradiation therapy.

Results

Forty-nine patients were enrolled in this study and forty-three of the patients completed the treatment. The median duration of follow-up was 18 months (range, 6~39 months). All of the patients had stage III (26.5%) or IV (73.5%) squamous cell carcinoma. After sequential therapy, a complete response and partial response was seen in 28 (65.2%) and 13 (30.2%) patients, respectively. The overall response rate was 95.4%. Overall survival and progression-free survival (PFS) at 2 years were 88.7% and 69.7%, respectively. Grade 3~4 neutropenia occurred in 42.2% of the patients and grade 4 thrombocytopenia in 1 cycle (0.7%). Two patients (4.1%) died during the induction chemotherapy due to pneumonia and a subdural hemorrhage, respectively. The group of patients over 65 years of age showed a significant lower dose intensity than that of patients under 65 years of age, but PFS was not significantly different between two groups (p=0.105).

Squamous cell cancer of the head and neck (SCCHN) is a potentially curable tumor when it is diagnosed early and treated adequately (1). However, approximately two-thirds of patients with SCCHN present with locoregionally advanced disease and median age of patients presenting with a SCCHN is over 60 years. Advanced disease frequently recurs after optimal local treatment. Over half of patients will develop a locoregional recurrence within 2 years, and 20~30% of these patients will develop distant metastases. Therefore, the 3- to 5-year survival rates remain at just 20~40% for patients (2,3). To improve the results of treatment, control of local recurrence and distant metastases is important. Recently, randomized trials have shown that induction chemotherapy followed by radiation therapy is equivalent to surgery in terms of the survival rate, with a significant advantage of organ preservation (4). The most commonly used regimen is the combination of cisplatin and fluorouracil (CF). This chemotherapy regimen showed a response rate of 67~70%, with a complete response (CR) rate of 19~27% (5). Usually, the CR rate can be a predictor of locoregional control.

Docetaxel, one of the most active agents against SCCHN, yields a response rate of approximately 35% (6). Recent reports have shown that combination chemotherapy with the addition of docetaxel to CF induces a better response rate (7~9). The results from the above trial have suggested a significant improvement in the response rate with the addition of a taxane. Therefore, docetaxel has been incorporated in the regimen for increased efficacy of induction treatment. However, bone marrow toxicity, such as neutropenia, was higher than seen with previous 5-FU and cisplatin chemotherapy regimens; therefore, its continued management is important (10).

This study was performed to determine the feasibility and safety of induction chemotherapy with docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil followed by concurrent chemoradiation therapy for advanced SCCHN. The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the response rate and survival benefits of this treatment. In addition, we assessed the toxicities and analyzed the results according to age to define the efficacy and tolerability of the combined regimen in elderly patients.

All patients had a confirmed stage III or IV SCCHN of the oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx, larynx, and/or nasopharynx, and had undergone neither chemotherapy nor radiation therapy. Patients were required to be 18 years of age or older and have an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 to 2. In addition, patients required adequate bone marrow, hepatic, and renal function (white blood cell count ≥3,000/mm3, granulocytes ≥1,500/mm3, platelets ≥100,000/mm3, total bilirubin <1.3 mg/dl, and creatinine clearance >60 ml/min) prior to undergoing chemotherapy. Pretreatment staging involved examination of the ears, nose, and throat, as well as a computed tomographic (CT) scan of the primary tumor site and neck. Patients were excluded if they had a concomitant malignancy. To detect other primary aerodigestive tract malignancies, patients underwent a CT scan of the chest and an esophago-gastroduodenoscopy or pharyngo-esophagogram.

Docetaxel (70 mg/m2) and cisplatin (75 mg/m2) were given as a 1-hour intravenous infusion on day 1, followed by 5-FU (1,000 mg/m2) as a 24-hour continuous infusion for 4 days. Cycles were repeated every 3 weeks. Thirty minutes prior to the docetaxel infusion, each patient received 20 mg dexamethasone, 50 mg ranitidine, and 5 mg chlorpheniramine maleate intravenously to prevent hypersensitivity reactions. After prehydration with at least 1 L normal saline; the calculated dose of docetaxel, diluted in 300 ml normal saline was infused over 1 hour. The calculated dose of cisplatin, diluted in 500 ml normal saline, was then administered over 1-hour, followed by posthydration with 3 L normal saline over 24 hours. Soon after the cisplatin infusion was completed, 5-FU was infused continuously for 4 days. Ondansetron (8 mg, i.v) was routinely given. Patients received further cycles of chemotherapy only when the absolute neutrophil count was ≥1,000/mm3 and platelets were ≥150,000/mm3. Toxicity was graded according to NCI-CTC version 2.0. Dose modifications were determined by hematological or non-hematological toxicities. The dose of docetaxel was reduced after any episode of febrile neutropenia or grade 4 neutropenia lasting more than 5 days, or grade 4 thrombocytopenia or greater than grade 3 asthenia. The cisplatin dose was reduced to 75% of the original dose in subsequent cycles if one of the following occurred: greater than grade 3 sensory neurotoxicity, or grade 2 or greater nephrotoxicity, persistent grade 4 neutropenia or neutropenic fever after dose reduction of docetaxel. For patients with grade 3 diarrhea that lasted for more than 7 days despite the administration of loperamide or for mucositis grade 3 lasting for more than 5 days or grade 4 mucositis, a 25% reduction in the daily dose of 5-FU was required.

After 3 cycles of induction chemotherapy, intravenous cisplatin at a dose of 100 mg/m2 on days 1 and 22 was administered concomitantly with conventional radiotherapy to the primary tumor with a total dose of 68.4 Gy. Radiotherapy was performed using 6-MV photon beams produced by a 21 EX or 21 iX linear accelerator. All patients were treated using standard radiotherapy technique in daily 1.8 or 2 Gy of fraction, 5 days per week. The gross neck node had a boost treatment with a 9- or 12-MeV electron beam.

After three cycles of induction chemotherapy and concurrent chemoradiation therapy, patients were assessed for clinical response underwent examination of the ears, nose, and throat by an otolaryngologist, as well as CT imaging of the primary tumor and neck. A biopsy of the primary site was recommended. The criteria for response were based on WHO criteria. When treatment was completed, patients were observed for an evaluation of disease status by a monthly physical examination and monitoring of toxicity and CT scanning every 3 months until disease progression.

Complete response (CR) was defined as the disappearance of all known lesions. A pathological complete clinical response was defined as no evidence of tumor in the primary site biopsy. A partial response (PR) for a bidimensionally measurable lesion was defined as at least a 50% decrease in the sum of the products of the largest perpendicular diameter of all measurable lesions. For PR, it was not necessary for all measurable lesions to regress, but there could be no progression and no new lesions. Stable disease was defined as less than a 50% decrease or a 25% increase in the sum of the products of the largest perpendicular diameters of all measurable lesions. For unidimensionally measurable disease, stable disease was defined as less than a 30% decrease or a 20% increase in the sum of the largest diameters of all measurable lesions. Progressive disease was defined as more than a 25% increase in the sum of the products of the largest diameters of all measurable lesions or the appearance of any new lesions.

Toxicity for patients under 65 years and over 65 years were compared using the χ2 test for categoric variables. Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) were calculated using the method of Kaplan and Meier. The PFS between two groups were compared with the log-rank test and p<0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

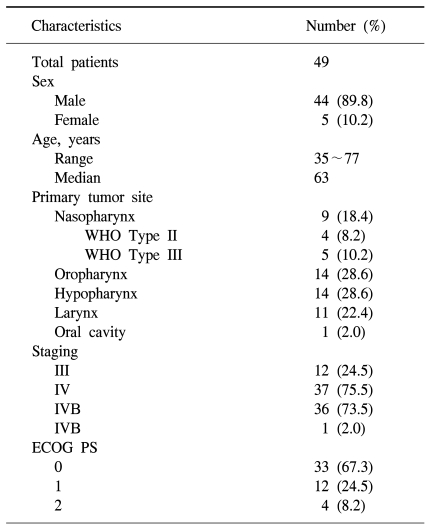

Forty-nine patients were enrolled in the study between May 2004 and January 2007. All of patients received induction chemotherapy, but two patients died of aspiration pneumonia and a subdural hemorrhage. After completion of induction chemotherapy, four of the forty-seven patients dropped out of the study. Two patients were lost to follow-up and another two patients refused radiation therapy because of economic issues and poor general condition. Thus, a total of forty-three patients completed the sequential chemoradiation treatment. One patient had not received an evaluation of treatment response after sequential treatment because of follow up loss. Therefore, 42 patients could be evaluated after the completion of treatment. Forty-four men and five women were enrolled initially, with a median age of 63 years (range, 35 to 77 years). Twelve (24.5%) patients had a stage III carcinoma and thirty-seven (75.5%) patients had a stage IV carcinoma without a distant metastasis (Table 1).

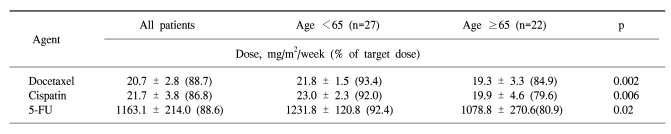

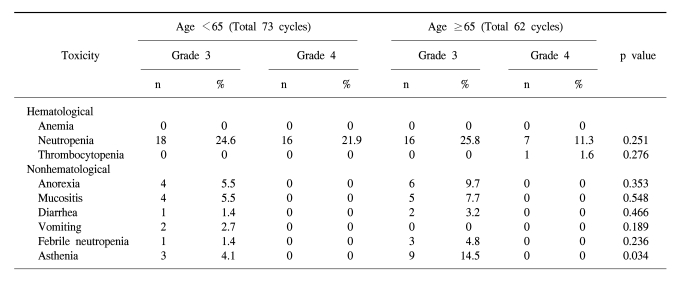

In the forty-nine patients, a total of 146 cycles of TPF was performed. One patient received only two cycles of TPF chemotherapy because of disease progression. The median treatment duration of induction chemotherapy was 9.6 weeks. The dose intensity of docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-FU were 88.7%, 86.8%, and 88.6% of the target dose, respectively (Table 2). To evaluate efficacy and safety according to age, we compared the dose intensities between the group of patients under 65 years and the group of patients over 65 years. Dose intensities were significantly different between the two groups in relation to docetaxel (93.4% of target dose in the <65 years group and 84.9% in the ≥65 years group of patients, p=0.002), to cisplatin (92.0% of the target dose in the <65 years group and 79.6% in the ≥65 years group of patients, p=0.006) and to 5-FU (92.4% of the target dose in the <65 years group and 80.9% in the ≥65 years group of patients, p=0.02). The most common cause of decreased dose intensity in the elderly group was related to asthenia and creatinine clearance.

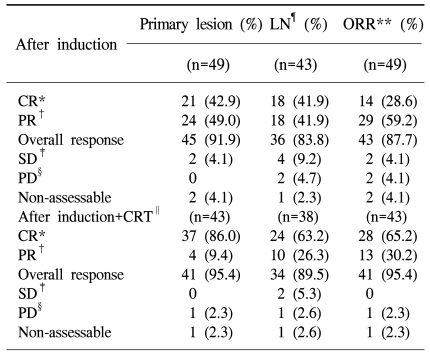

After induction chemotherapy, 21 [42.9%, 95% confidence interval (CI) 28.8~57.8%] and 24 (49.0%, 95% CI 34.4~63.7%) patients achieved CR and PR in the primary site, respectively. In the neck lymph nodes, 43 patients showed a lymph node metastasis. In these patients, 18 (41.9%, 95% CI 27.0~57.9%) patients achieved CR and 18 (41.9%, 95% CI 27.0~57.9%) patients achieved PR. The overall response of induction chemotherapy was 87.7% (CR: 28.6%, PR: 59.2%; 95% CI 75.2~95.4%). After sequential chemoradiation therapy, 37 (86.0%, 95% CI 72.1~94.7%) patients showed CR in the primary site, including 23 (53.5%, 95% CI 37.7~68.8%) cases of pathological CR. Four (9.4%) patients showed a PR. In the neck lymph nodes, 24 (63.2%) out of 38 patients achieved CR and 10 (26.3%) patients achieved PR, but one patient showed progressive disease. Overall, 28 (65.2%, 95% CI 49.1~79.0%) out of 43 patients achieved CR, 13 (30.2%, 95% CI 17.2~46.1%) achieved PR, and one patient showed progressive disease (2.3%) (Table 3).

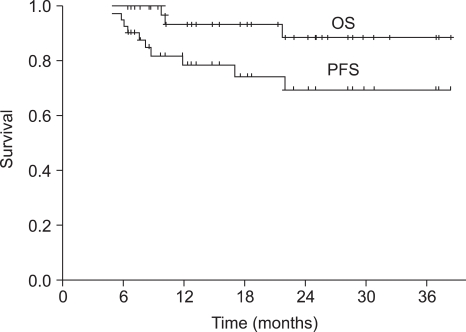

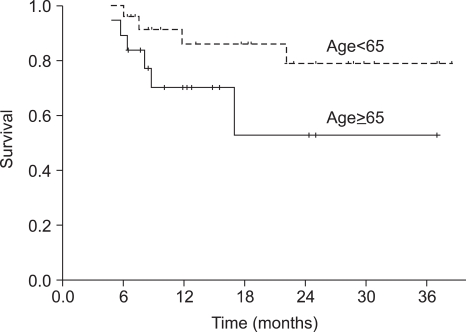

The median duration of follow-up was 18 months (range, 6~39 months) for the overall patient population. The median OS was not reached at this time. The 1-year and 2-year OS rate was 93.6% (95% CI 89.3~97.9%) and 88.7% (95% CI 82.4~95.0%), respectively (Fig. 1). Progression-free survival (PFS) at 1-year and 2-years was 78.9% (95% CI 72.2~85.6%) and 69.7% (95% CI 61.2~78.2%), respectively (Fig. 1). The PFS of the group of patients under the age of 65 was not significantly different from that of the group of patients over the age of 65 (p=0.105) (Fig. 2).

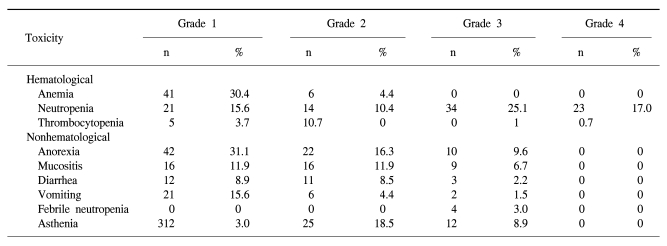

The toxicity of TPF chemotherapy was assessed in all 49 patients, and 135 of all 146 cycles of TPF was analyzed (Table 4). The mean times to nadir values for absolute neutrophils, hemoglobin, and platelets were between 7 and 10 days after the completion of chemotherapy. A greater than grade 3 neutropenia occurred in 42.2% of the patients. Febrile neutropenia developed in four cycles of chemotherapy. Grade 4 thrombocytopenia was observed in only one patient. Two patients died during induction therapy because of aspiration pneumonia and a subdural hemorrhage, respectively. The patient that died of the subdural hemorrhage had alcoholic liver cirrhosis with splenomegaly, although the liver function at the beginning of chemotherapy was Child-Pugh Class A. After completion of the third cycle of TPF chemotherapy, the patient came to the hospital with a severe headache. Nevertheless, the patient showed a CR after response evaluation, but a subdural hematoma was noted. The patient refused further definitive treatment and died. Therefore, treatment related deaths occurred in 4.1% of the patients. The most common non-hematologic toxicities were asthenia and anorexia. Asthenia below grade 2 and anorexia below grade 2 developed in 41.5% and 47.4% of the patients, respectively. However, asthenia over grade 3 and anorexia over grade 3 developed in only 8.9% and 9.6% of the patients, respectively. There was a significant difference between the group of patients under age 65 years and over 65 years of age for asthenia (p=0.034) (Table 5).

The use of induction chemotherapy with CF in patients with SCCHN has been studied for over two decades. To improve the efficacy over CF, the addition of a third drug to CF has been previously studied (8,10). The use of docetaxel is promising both for its inherent antineoplastic activity in SCCHN and as a radiation sensitizer. Docetaxel has the advantage of a longer intracellular half-life that leads to higher intracellular levels of docetaxel in the steady state (11). Furthermore, docetaxel is 100 times more potent than paclitaxel with respect to bcl-2 phosphorylation and inactivation, and may act in addition to tubulin stabilization (12). Recently, the taxanes have shown considerable activity in recurrent disease and have been investigated in combination chemotherapy with CF as the induction chemotherapy (10,13,14).

The combination of docetaxel to CF has been studied in phase II studies (14~17). The TAX708 phase I/II multicenter study of TPF suggested that it showed easily controlled toxicity and excellent long-term survival; the complete response rate was 40%, and the pathological complete response rate was 90%. The overall response rate was 93%, and the overall survival rates at 12 months, 18 months, and 24 months were 98%, 90%, and 82%, respectively (13). In a similar phase III trial conducted by Hitt et al., survival and organ preservation were better in the TpPF (with paclitaxel) arm than in the CF arm, suggesting that the triple drug combination was better (10).

Based on recent reports evaluating TPF or TPFL (TPF+ leucovorin) in SCCHN, the main issue with treatment failure was locoregional recurrence (13,18). A combination with induction chemotherapy and chemoradiation therapy in a sequential treatment plan, based on differences in activity and toxicity of each paradigm, could improve outcomes with intensification of local treatment (5,10,19). The study conducted by Hitt et al. was designed that for sequential chemoradiation therapy after induction chemotherapy, it was shown that the median survival of the TpPF (with paclitaxel) sequential therapy group (35.9 months) was longer than CF sequential therapy group (25.8 months) (p=0.033) (10). In the present study, the overall response after induction chemotherapy was found to be 87.7% (CR: 28.6%, PR: 59.2%). After completion of chemoradiotherapy, 28 (65.2%) out of 43 patients achieved CR and 13 (30.2%) patients achieved PR. This result suggested that sequential therapy in SCCHN could increase CR. The CR rate can predict the locoregional control. Therefore, induction chemotherapy followed by chemoradiotherapy can improve the outcome of SCCHN.

Generally, the median age of patients with head and neck cancers is over 60 years (20). In elderly patients, the capacities of bone marrow and other vital organs are vulnerable to toxic stimuli, and are associated with the incidence of myelotoxicity in patients over 65 years of age when treated with chemotherapy (21~23). Some trials have indicated that the dose intensity is lowered significantly in a substantial proportion of patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy, possibly due to the fear of toxicity (24). In our study, the actual dose intensities were lower than the target dose in the elderly group because of asthenia. These issues resulted in a reduction in dose or a delay in the start of chemotherapy, but it did not influence the PFS between the two groups of patients. Although the elderly patient group was subjected to a dose modification of the chemotherapy, the TPF regimen was effective for elderly patients (25).

TPF chemotherapy followed by chemoradiotherapy is a highly effective treatment in terms of response and PFS with manageable toxicities. Furthermore, given the result that dose modification did not decrease PFS, this treatment is warranted in elderly patients with adequate dose modification.

References

1. Forastiere A, Koch W, Trotti A, Sidransky D. Head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001; 345:1890–1900. PMID: 11756581.

2. Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Smigal C, et al. Cancer statistics, 2006. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006; 56:106–130. PMID: 16514137.

3. Lefebvre JL, Chevalier D, Luboinski B, Kirkpatrick A, Collette L, Sahmoud T. Larynx preservation in pyriform sinus cancer: preliminary results of a European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer phase III trial. EORTC Head and Neck Cancer Cooperative Group. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996; 88:890–899. PMID: 8656441.

4. Guadagnolo BA, Haddad RI, Posner MR, Weeks L, Wirth LJ, Norris CM, et al. Organ preservation and treatment toxicity with induction chemotherapy followed by radiation therapy or chemoradiation for advanced laryngeal cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2005; 28:371–378. PMID: 16062079.

5. Pignon JP, Bourhis J, Domenge C, Designe L. Chemotherapy added to locoregional treatment for head and neck squamous-cell carcinoma: three meta-analyses of updated individual data. MACH-NC Collaborative Group. Meta-Analysis of Chemotherapy on Head and Neck Cancer. Lancet. 2000; 355:949–955. PMID: 10768432.

6. Janinis J, Papadakou M, Xidakis E, Boukis H, Poulis A, Panagos G, et al. Combination chemotherapy with docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil in previously treated patients with advanced/recurrent head and neck cancer: a phase II feasibility study. Am J Clin Oncol. 2000; 23:128–131. PMID: 10776971.

7. Catimel G, Verweij J, Mattijssen V, Hanauske A, Piccart M, Wanders J, et al. EORTC Early Clinical Trials Group. Docetaxel (Taxotere): an active drug for the treatment of patients with advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Ann Oncol. 1994; 5:533–537. PMID: 7918125.

8. Lee JH, Lee KW, Choi YJ, Choi JH, Shin HJ, Chung JS, et al. Docetaxel and cisplatin combination chemotherapy in patients with squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. Cancer Res Treat. 2003; 35:261–266.

9. Hitt R, Paz-Ares L, Brandariz A, Castellano D, Pena C, Millan JM, et al. Induction chemotherapy with paclitaxel, cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: long-term results of a phase II trial. Ann Oncol. 2002; 13:1665–1673. PMID: 12377658.

10. Hitt R, Lopez-Pousa A, Martinez-Trufero J, Escrig V, Carles J, Rizo A, et al. Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus fluorouracil to paclitaxel, cisplatin, and fluorouracil induction chemotherapy followed by chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005; 23:8636–8645. PMID: 16275937.

11. Diaz JF, Andreu JM. Assembly of purified GDP-tubulin into microtubules induced by taxol and taxotere: reversibility, ligand stoichiometry, and competition. Biochemistry. 1993; 32:2747–2755. PMID: 8096151.

12. Haldar S, Basu A, Croce CM. Bcl2 is the guardian of microtubule integrity. Cancer Res. 1997; 57:229–233. PMID: 9000560.

13. Posner MR, Glisson B, Frenette G, Al-Sarraf M, Colevas AD, Norris CM, et al. Multicenter phase I-II trial of docetaxel, cisplatin, and fluorouracil induction chemotherapy for patients with locally advanced squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. J Clin Oncol. 2001; 19:1096–1104. PMID: 11181674.

14. Haddad R, Colevas AD, Tishler R, Busse P, Goguen L, Sullivan C, et al. Docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil-based induction chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: the Dana Farber Cancer Institute experience. Cancer. 2003; 97:412–418. PMID: 12518365.

15. Colevas AD, Busse PM, Norris CM, Fried M, Tishler RB, Poulin M, et al. Induction chemotherapy with docetaxel, cisplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: a phase I/II trial. J Clin Oncol. 1998; 16:1331–1339. PMID: 9552034.

16. Colevas AD, Norris CM, Tishler RB, Fried MP, Gomolin HI, Amrein P, et al. Phase II trial of docetaxel, cisplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as induction for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. J Clin Oncol. 1999; 17:3503–3511. PMID: 10550148.

17. Colevas AD, Norris CM, Tishler RB, Lamb CC, Fried MP, Goguen LA, et al. Phase I/II trial of outpatient docetaxel, cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin (opTPFL) as induction for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN). Am J Clin Oncol. 2002; 25:153–159. PMID: 11943893.

18. Posner MR, Haddad RI, Wirth L, Norris CM, Goguen LA, Mahadevan A, et al. Induction chemotherapy in locally advanced squamous cell cancer of the head and neck: evolution of the sequential treatment approach. Semin Oncol. 2004; 31:778–785. PMID: 15599855.

19. Tae K, Keum HS, Kang SY, Lee HS, Choi JH, Kim IS, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by concurrent chemoradiation in locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Korean J Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2007; 50:327–334.

20. Vokes EE. Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Hauser ST, Longo DL, Jameson JL, editors. Head and neck cancer. Harrison's principles of internal medicine. 2004. 16th ed. Seoul: McGraw-Hill;p. 501.

21. Gomez H, Mas L, Casanova L, Pen DL, Santillana S, Valdivia S, et al. Elderly patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma treated with CHOP chemotherapy plus granulocytemacrophage colony-stimulating factor: identification of two age subgroups with differing hematologic toxicity. J Clin Oncol. 1998; 16:2352–2358. PMID: 9667250.

22. Lyman GH, Dale DC, Crawford J. Incidence and predictors of low dose-intensity in adjuvant breast cancer chemotherapy: a nationwide study of community practices. J Clin Oncol. 2003; 21:4524–4531. PMID: 14673039.

23. Dees EC, O'Reilly S, Goodman SN, Sartorius S, Levine MA, Jones RJ, et al. A prospective pharmacologic evaluation of age-related toxicity of adjuvant chemotherapy in women with breast cancer. Cancer Invest. 2000; 18:521–529. PMID: 10923100.

24. Schild SE, Stella PJ, Geyer SM, Bonner JA, McGinnis WL, Mailliard JA, et al. The outcome of combined-modality therapy for stage III non-small-cell lung cancer in the elderly. J Clin Oncol. 2003; 21:3201–3206. PMID: 12874270.

Fig. 1

Progression free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) for all patients (n= 42). The 1-year and 2-year OS rate was 93.6% (95% CI 89.3~97.9%) and 88.7% (95% CI 82.4~95.0%), respectively. Progression-free survival (PFS) at 1-year and 2-years was 78.9% (95% CI 72.2~85.6%) and 69.7% (95% CI 61.2~78.2%).

Fig. 2

Progression-free survival (PFS) according to age; the PFS at 2 years of the group of patients under the age of 65 years was longer than that of the group of patients over the age of 65 years, at 78.5% (95% CI, 68.7~88.3%) and 52.4% (95% CI, 35.0~69.8%), respectively (p=0.105).

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download