Abstract

Purpose

We wanted to analyze the use of nutrition support for terminal cancer patients, the effect of discussing withdrawal of nutrition support and do-not-resuscitate (DNR) consent on the use of intravenous nutrition during the patient's last week of life and at the time of death.

Materials and Methods

The study involved 362 patients with terminal cancer from four teaching hospitals, and they all died between January 1 2003 and December 31 2005. The basic demographic data, the use of intravenous nutrition during the patient's last week of life and at death, discussion of terminal nutrition withdrawal and DNR consent were evaluated.

Results

In the week before death, the patients received artificial nutrition such as total parenteral nutrition (31%), intravenous albumin infusion (25%), and feeding tube placements (9%). A discussion concerning withdrawal of nutrition support was limited to 25 (7%) patients. DNR consent was obtained from 294 (81%) patients. None of the patients were directly involved in any of these decisions. The discussion about withdrawal of terminal nutrition and DNR consent with the patient's surrogates did not have any effect on reducing the use of parenteral nutrition.

Conclusion

The majority of patients dying of terminal cancer were still given potentially futile nutritional support. Modern clinical guidelines and ethical education about nutritional support at the end of life care is urgently needed in Korean medical practice to provide proper administration of terminal nutrition for end of life care.

Go to :

More than 80% of patients with malignant disease suffer from weight loss and malnutrition during the course of their illness (1). Therefore, it is naive to view nutritional support for patients with advanced cancer as simply an exercise in correcting malnutrition by replacing protein and providing sources of energy in sufficient quantities.

Large randomized controlled studies have tried to demonstrate if aggressive nutritional therapy for patients with advanced cancer could improve the tumor response or survival (2,3). However, all of these studies failed to show any clinical benefit, including any benefit for the patient's quality of life. Currently, it is widely recognized that the routine practice of artificial nutrition for patients with terminal cancer has no value to the patient.

However, the decision to use or forgo artificial nutrition during the care of terminal cancer patients remains a perplexing and emotional issue to the patients, their families and the medical staff caring for them. In our society, because many cancer patients are not given a truthful statement about their diagnosis and prognosis, the decision to withdraw nutritional support has been made by either the family of the patient or by the next of kin; consequently, this is a very distressful process. Moreover, many of the medical professionals in Korea still lack expertise for properly and comfortably managing these issues.

Therefore, to better understand how terminal nutrition is administered and to provide guidelines for programmatic reforms to ease this potential medical futility, we examined the practice of using terminal nutrition at teaching hospitals in Korea.

Go to :

This is a retrospective descriptive study. From January 1 2003 to December 31 2005, we reviewed the data from 362 terminal cancer patients who were admitted at least one week prior to death at four major teaching hospitals. All the patients had detailed medical records, including the site of their cancer, the orders for terminal nutrition from the attending physicians and the details on their end of life care.

The use of total parenteral nutrition (TPN), albumin and tube feeding was obtained from the patients' charts within one week and at the time of death. Their medical indications and actual use were totally dependent on the orders of the attending resident or staff physician for each individual patient. The occurrence of a discussion about withdrawing terminal nutrition was determined as was shown in the medical records if a discussion about the insignificant benefit and potential harm of intravenous nutrition for terminal ill patients was provided by the attending physician.

To better understand the practice patterns of intravenous nutrition related to the end of life decisions, we investigated whether there was a correlation between the reduction of intravenous nutrition at the time of the patient's death and the occurrence of a discussion about withdrawing terminal nutrition. We also studied the relationship between the reduction of intravenous nutrition use at the time of the patient's death and the use of "do not resuscitate" (DNR) consent for all of the enrolled patients. The definition of DNR was not to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) procedures. CPR was defined as application of external chest compression and rescue breathing. The consent for DNR was considered present if there was a written document or a medical note about DNR permission from the patient's families during the hospitalization.

Statistical methods were used to analyze the difference of the variables that were important for the evaluation of the discussion of withdrawing nutrition support, the DNR consent and the use of intravenous nutrition at the time of death of the patient. Fisher's exact test was performed and the results were considered significant if the the p values were <0.05.

Ethical approval for this study was given by the individual Institutional Review Board of each hospital.

Go to :

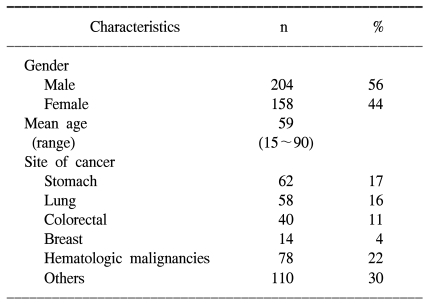

The selected patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. All the patients were in the terminal stage of their diseases, and they had a poor performance status. The patients ranged in age from 15 to 90 years of age. The diagnoses included 62 stomach cancers, 58 lung cancers, 40 colorectal cancers, 14 breast cancers, 78 hematologic malignancies and 110 various other cancers.

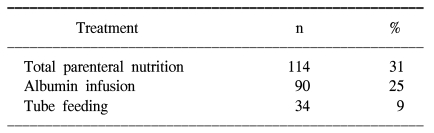

Table 2 summarizes the number of patients who received artificial nutrition for the last week of their life. TPN was given to 114 (31%) of the patients. Among them, 64 (56%) patients still received TPN at the time of their death. All patients had intravenous access for provision of fluids. Albumin was infused to 90 (25%) of patients and 9 (3%) patients had received albumin at the time of death. Tube feeding was performed for 34 (9%) patients. Nearly all of the patients were kept on tube feeding until their death.

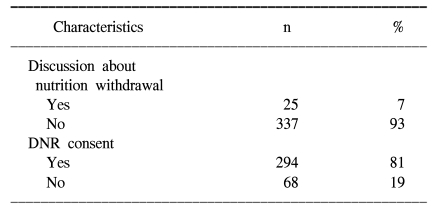

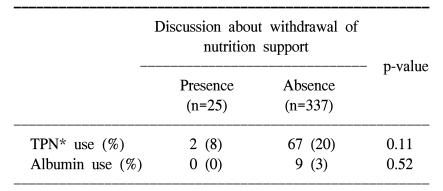

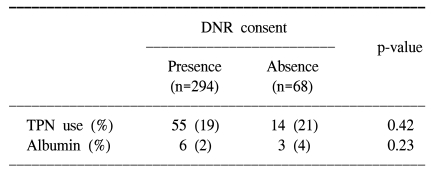

As shown Table 3, a discussion about withdrawal of nutritional support near the end of life occurred for 25 (7%) patients. DNR consents were done for 294 (81%) patients. None of the patients was directly involved in these decisions. Table 4 compares the use of intravenous nutrition on the day of patient's death to the occurrence of discussion about withdrawal of terminal nutrition. While 67 out of 337 (20%) patients received TPN when a discussion about withdrawal of terminal nutrition had not been done, 2 out of 25 (8%) patients received TPN with such a discussion (p=0.11).

Go to :

In this retrospective, descriptive study, we found that TPN was given to 114 (31%) patients and intravenous albumin was given to 90 (25%) patients at least one time during the last week of the life of the patients. Moreover, TPN was given to 69 (19%) patients at the time of their death. Any discussion about withdrawing terminal nutrition at the end of life was rarely performed. Even though the use of TPN and albumin tended to be reduced for the patients whom discussion about withdrawal of nutrition support was given at the end of life, there was no significant difference seen for the patients for whom a discussion was not done concerning withdraw of terminal nutrition. Also, DNR consent had no effect on the reduction of intravenous nutrition used for the terminal cancer patients. Our study demonstrated that the terminal cancer patients, whose death was thought to be imminent, routinely received potentially futile artificial nutrition at the teaching hospitals.

The decisions related to nutritional support for terminally ill patients are not usually made in isolation, but they involve an assessment of the underlying disease, the patient and their wishes, and a nutritional evaluation that defines specific nutritional needs and requirements (4,5). From the point of view of the physicians, the key factor for whether the patient should be supported with nutritional support might clearly be the performance of the patient in terms of their tasks of daily living and their quality of life. Therefore, nutritional support for terminal cancer patients should be done as part of an overall care plan that involves input from the patient and their attending physicians.

A large number of studies have consistently demonstrated that there is little clinical benefit for giving artificial nutrition for end of life care (2,3). Our data reflects that although many physicians consider intravenous nutrition to be the minimum standard of care for terminal cancer patients, most of them base their decisions on local cultural practices, and not evidence based practice. A similar study conducted in Taiwan (6) is also consistent with our results, that no reduction of using terminal nutrition was observed during the last days prior to death.

Moreover, a serious problem was that continuation of nutritional support was not requested. As we have shown, any discussion about withdrawal of artificial nutrition as a part of end of life care rarely occurred between the physician and the patient's families. We did not find any significant relationship between a discussion about withdrawing terminal nutrition and the use of intravenous nutrition around the time of death. There are two possible explanations that can be considered. First, the family might not accept the guidance of the physician about withdrawing terminal nutrition. Second, biases might have been present if the discussions on withdrawing terminal nutrition had not been recorded because our findings were based on the data recorded in the medical records. Previous evidence (7) suggests that competent patients, when given a choice, often limit food and fluid intake voluntarily when the primary goal is comfort and avoidance of suffering. Because none of our patients were involved in the end of life decision making, including the issue of withdrawal of terminal nutrition, we were not able to evaluate the wishes of the patients themselves concerning the end of life care. Therefore, our finding suggests that there is considerable room for improving the practice of withdrawing terminal nutrition, especially if the patient themselves can be included in the discussions. The encouraging fact is that that most cancer patients want more disclosure of information, which is in contrast to the traditional belief concerning the patient's families.

Discussions about end of life issues have recently gained increased attention in both medical and lay publications (8, 9). Terminally ill patients in Western countries can specify their medical care for end of life situations in an advanced directive document, such as a living will or a durable power of attorney of health care (10,11). Considering the cultural background, a living will or advance directive is not a usual medical practice for terminally ill patients in Korea. However, a physician may honor a request of the patient to limit aggressive treatment by writing a DNR order. The real problem lies with the scale of the DNR. A DNR order definitely should indicate the advantage of decreased mechanical ventilator support, decreased invasive and painful intervention for the patient, and in general, a decreased economic burden. In fact, we observed that the format of the DNR consent varied according to the different hospitals. The purpose of DNR consent was broadly interpreted in two ways. For those patients whom a DNR consent was obtained in two hospitals, it was considered that it forbade resuscitation only, whereas for those patients whom the DNR consent was made in another two hospitals, it implied that only palliative (symptom oriented) care would occur, and it forbid invasive intervention, mechanical ventilator support and transfer to the intensive care unit (ICU). Predetermined categories of DNR so as to order no treatments (antibiotics, hemodialysis, ICU transfer etc) were present on the limited care DNR consent. Yet there was no place to enter a request to withhold or withdraw artificial administration of food and fluids. Therefore, it is important to note that our results showed that there was no correlation between the reduction of intravenous nutrition at death and consent for DNR. We suggest that withdrawal of terminal nutrition might be performed as part of the rationale behind instituting a DNR order for patients with terminal cancer.

Our study has several limitations that need to be considered, and some of these limitations are inherent in the study design. First, our data may not be able to be generalized several other teaching hospitals. Second, the study was retrospective in design, so other factors like the nutritional needs of the patients, the exact nutrition status of the patients and the effects of such patient's demographics as the socio-economic status, religion and education level on terminal nutrition use were not evaluated.

Go to :

There was a high prevalence of administering terminal nutrition in our study. Delicate care and continuing communication with a patient's family, and involvement of the patient himself can be helpful in avoiding unnecessary artificial nutrition (12). Most importantly, it is necessary to establish evidence-based guidelines for the withdrawal or withholding of terminal nutrition via a prospective cohort study. Adopting a patient centered method such as an informed consent on a DNR order and setting a level of care would important steps in deciding whether it is futile to provide terminal nutrition at the end of life.

Go to :

References

1. Inui A. Cancer anorexia-cachexia syndrome: current issues in research and management. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002; 52:72–91. PMID: 11929007.

2. Koretz RL. Parenteral nutrition: is it oncologically logical? J Clin Oncol. 1984; 2:534–538. PMID: 6427418.

3. Klein S, Koretz RL. Nutritional support in patients with cancer: what do the data really show? Nutr Clin Pract. 1994; 9:91–100. PMID: 8078449.

4. McKinlay AW. Nutritional support in patients with advanced cancer: permission to fall out? Proc Nutr Soc. 2004; 63:431–435. PMID: 15373954.

5. Barrera R. Nutritional support in cancer patients. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2002; 26(5):Supple. S63–S71. PMID: 12216725.

6. Chiu TY, Hu WY, Chuang RB, Chen CY. Nutrition and hydration for terminal cancer patients in Taiwan. Support Care Cancer. 2002; 10:630–636. PMID: 12436222.

7. Dunlop RJ, Ellershaw JE, Baines MJ, Sykes N, Saunders CM. On withholding nutrition and hydration in the terminally ill: has palliative medicine gone too far? J Med Ethics. 1995; 21:141–143. PMID: 7545757.

8. Oh DY, Kim JH, Kim DW, Im SA, Kim TY, Heo DS, et al. CPR or DNR? End of life decision in Korean cancer patients: a single center's experience. Support Care Cancer. 2006; 14:103–108. PMID: 16151752.

9. Oh DY, Kim JE, Lee CH, Lim JS, Jung KH, Heo DS, et al. Discrepancies among patients, family members, and physicians in Korea in terms of values regarding the withholding of treatment from patients with terminal malignancies. Cancer. 2004; 100(9):1961–1966. PMID: 15112278.

10. Ditto PH, Danks JH, Smucker WD, Bookwala J, Copppola KM, Dresser R, et al. Advance directives as acts of communication: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2001; 161:421–430. PMID: 11176768.

12. Gillick MR. The use of advance care planning to guide decisions about artificial nutrition and hydration. Nutr Clin Pract. 2006; 21:126–133. PMID: 16556922.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download