Abstract

Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas (SPTP) is a rare primary pancreatic tumor of an unknown etiology that is usually diagnosed in adolescent girls and young women. Most SPTPs are considered to be benign and only rarely metastasize. We report here on a 27-year old woman with recurrent SPTP with involvement of both the spleen and left kidney at the time of the initial diagnosis, and with aggressive behavior. In July 1995, she was admitted with abdominal discomfort and mass. She underwent exploratory laparotomy with distal pancrea tectomy, left nephrectomy and splenectomy, and was diagnosed with SPTP with invasion to both the spleen and left kidney. In June 2001, she again presented with abdominal pain and was diagnosed as having recurrence of the tumor. She underwent mass excision and omentectomy. Then she was lost to follow-up. In November 2005, she presented once again with an abdominal mass and was diagnosed with recurred SPTP, which formed a huge intraperitoneal mass with peritoneal seeding and the tumor showed multiple metastases in the liver. She is currently being treated conservatively.

Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas (SPTP) was initially described by Frantz in 1959 (1). Most SPTPs have been described as being benign in nature, although 10% to 15% of SPTPs show malignant behavior and metastasis (2). The common sites of metastasis are liver, peritoneum, omentum and lymph nodes (3). However, there are few reported cases of SPTP with involvement of both the kidney and spleen at time of initial diagnosis. We report here on a case of recurrent SPTP that showed aggressive behavior and invasion to the spleen and left kidney at the time of initial presentation.

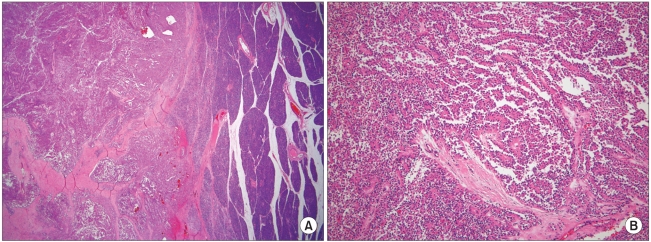

In July 1995, a 16 year-old girl presented with abdominal discomfort and mass, and she underwent exploratory laparotomy with distal pancreatectomy, left nephrectomy and splenectomy. At that time, a huge mass was found in the pancreatic tail with invasion to the spleen and left kidney, and it was approximately 20×20 cm with a weight of 1,400 gm. On section, the solid mass showed areas of cystic and necrotic changes. Microscopically, the tumor was surrounded by a capsule with tumor nests invading it and showed solid and pseudopapillary patterns (Fig. 1). On immunohistochemical study, there was positive staining for neuron specific enolase, synaptophysin and vimentin, and there was weak staining for cytokeratin. The staining for c-Kit, SMA, S-100, desmin, CD34, calretinin and chromogranin was negative. She was diagnosed as SPTP with involvement of both the spleen and left kidney. In June 2001, the patient underwent a second operation because of tumor recurrence in the peritoneum and omentum. Mass excision, omentectomy and incidental appendectomy were performed. After surgery, systemic chemotherapy was recommended, but was refused by the patient. Thereafter, she was lost to follow-up.

In November 2005, she came back to our hospital with complaints of abdominal pain and bloating. On physical examination, there was a huge mass occupying the right upper abdomen. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis confirmed multiple large masses that involved the entire liver, and there were multiple small masses in the peritoneal space with a small amount of ascites (Fig. 2). She was diagnosed with recurred SPTP. Transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) for the liver mass was considered, but it could not be performed because of the tumor's huge size, the presence of considerable necrosis and the hypovascularity of the mass. The patient is currently being treated conservatively.

Since it was first reported by Frantz in 1959, SPTP has been described as many other names such as papillary cystic neoplasm, solid and papillary epithelial neoplasm, papillary and solid neoplasm, papillary and cystic tumor, papillary cystic carcinoma, papillary cystic tumor, solitary cystic tumor, solid and cystic papillary epithelial neoplasm, Frantz's tumor or low grade papillary tumor. Because of their gross features and histology, SPTP is occasionally misdiagnosed as adenocarcinoma, islet cell tumor, cystadenoma, papillary cystadenoma or cystadenocarcinoma (4). In 1996, the World Health Organization renamed this neoplasm as SPTP in the international histological classification of tumors (5).

SPTP is a rare tumor and it represents approximately 1% of all pancreatic neoplasm (4). To date, approximately 700 cases of SPTP have been reported worldwide, and only case reports or small series have been reported domestically (1,11). The incidence of SPTP appears to be increasing due to a greater awareness of this disease, as well as a better understanding of pancreatic pathology according to the recommendations of the WHO. In a cumulative review of the literatures, Papvramidis found that 91% of the patients with this tumor were females with a mean age of 22 years, and the SPTP tended to be fairly aggressive in the older male patients (1). Clinically, the patients with SPTP usually present with vague abdominal pain or a mass. About 15.5% of the patients are reported to have been asymptomatic (1). As a result of the subtle symptoms, by the time a tumor is found at presentation it can be quite large. Grossly, SPTP appears as a well-encapsulated, spherical mass that usually measures around 8 to 10 cm (6). In our case, the size of the mass was approximately 20×20 cm and it weighted 1,400 gm. However, the size of a lesion is not a predictor of respectability; i.e., other studies have reported that the lesions 20 to 30 cm in size are resectable (7,8). The pathologic diagnosis of SPTP is based on the presence of its characteristics upon light microcopy. Solid areas alternating with pseudopapillary formations, evidence of cellular degeneration, nuclear grooves and aggregates of hyaline cytoplasmic globules are found, at least focally, in every case (4). The origin of this tumor remains an enigma and immunohistochemical staining for specific cell lineage markers has been of marginal utility in establishing the diagnosis of SPTP (9). Trypsin and chymotrypsin, which are markers of acinar differentiation, are consistently negative as is glycoprotein, a marker of ductal differentiation. Markers of neuroendocrine differentiation such as synatophysin have been found to be positive, although chromogranin is always negative. However, SPTPs show a characteristic immunohistochemical pattern: positivity for vimentin, neuron specific enolase and synaptophysin as well as cytokeratin, which is focally positive, although SPTPs lack specific lines of differentiation. Thus, the staining pattern may be helpful in the differential diagnosis of many pancreatic tumors such as pancreatic endocrine neoplasia and acinar cell carcinoma (10). In our case, immunohistochemical staining showed positivity for neuron specific enolase, vimentin, synaptophysin and cytokeratin.

Although SPTPs have a benign nature, 15% of SPTPs have been reported as being clinically aggressive (3). The common sites of metastasis are liver, peritoneum, omentum and lymph nodes (1). Nishihara et al. have compared the histological appearance of 19 non-metastasizing SPTPs and 3 metastasizing SPTPs, and they noted that venous invasion, the nuclear grade and prominent necrotic nests were the useful histological predictors for malignant potential (12). Kang et al. suggested that the SPTPs over 5 cm in diameter needed to be treated carefully because of the chance of malignant pathology (14). Regarding the treatment, surgery is the mainstay of treatment, and this is usually curative for localized disease. Even if this tumor spreads to other organs at the time of presentation, there is evidence for prolonged survival after adequate surgical resection (5,12,13). In a small domestic series, Kang et al. have reported that there was no recurrence after surgical excision, suggesting a favorable prognosis (11). Chemotherapy and radiotherapy have been used infrequently because most SPTPs can be successfully resected, although some reports indicate the significant success of chemotherapy and radiotherapy for treating the advanced lesions that were not completely resected (13). TAE has been reported as a useful treatment modality for liver metastasis; however, additional studies for determining the usefulness of TAE for treating SPTPs' liver metastasis are needed (15).

Our patient displayed a huge mass with invasion to both the kidney and spleen at the initial diagnosis, and the tumor pathology showed vascular invasion, prominent necrotic nests and capsular invasion. In addition, our patient showed repetitive tumor recurrence although surgical excision was performed. She is currently in a far advanced disease state and has multiple metastases that have involved the liver and peritoneum, and this suggests the aggressive nature of her tumor.

References

1. Frantz VK. Blumberg CW, editor. Tumors of pancreas. Atlas of tumor Pathology. 1959. 1st ed. Washington DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology;p. 32–33.

2. Papavramidis T, Papavramidis S. Solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas: review of 718 patients reported in English literature. J Am Coll Surg. 2005; 200:965–972. PMID: 15922212.

3. Mao C, Guvendi M, Domenico DR, Kim K, Thomford NR, Howard JM. Papillary cystic and solid tumors of the pancreas: a pancreatic embryonic tumor? Studies of three cases and cumulative review of the world's literature. Surgery. 1995; 118:821–828. PMID: 7482268.

4. Martin RC, Klimstra DS, Brennan MF, Conlon KC. Solid-psuedopapillary tumor of the pancreas: a surgical enigma? Ann Surg Oncol. 2002; 9:35–40. PMID: 11833495.

5. Kloppel G, Solcia E, Longnecker DS. Histological typing of tumors of the exocrine pancreas. WHO international histological classification of tumors. 1996. 2nd ed. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer.

6. Huang HL, Shih SC, Chang WH, Wang TE, Chen MJ, Chan YJ. Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: clinical experience and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2005; 11:1403–1409. PMID: 15761986.

7. Kingsnorth AN, Galloway SW, Lewis-Jones H, Nash JR, Smith PA. Papillary cystic neoplasm of the pancreas: presentation and natural history in two cases. Gut. 1992; 33:421–423. PMID: 1489379.

8. Cappellari JO, Geisinger KR, Albertson DA, Wolfman NT, Kute TE. Malignant papillary cystic tumor of the pancreas. Cancer. 1990; 66:193–198. PMID: 1693876.

9. Kosmahl M, Seada LS, Janig U, Harms D, Kloppel G. Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: its origin revisited. Virchows Arch. 2000; 436:473–480. PMID: 10881741.

10. Klimstra DS, Wenig BM, Heffess CS. Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: a typically cystic carcinoma of low malignant potential. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2000; 17:66–80. PMID: 10721808.

11. Kang H, Song YJ, Koh YS, Joo JK, Kim JC, Cho CK, et al. Clinical features and surgical treatment of solid pseudopapillary tumor of pancreas. J Korean Surg Soc. 2005; 68:492–497.

12. Nishihara K, Nagoshi M, Tsuneyoshi M. Papillary cystic tumors of the pancreas. Assessment of their malignant potential. Cancer. 1993; 71:82–92. PMID: 8416730.

13. Rebhandl W, Felberbauer FX, Puig S, Paya K, Hochschorner S, Barlan M, et al. Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas (Frantz tumor) in children: report of four cases and review of the literature. J Surg Oncol. 2001; 76:289–296. PMID: 11320522.

14. Kang CM, Kim KS, Choi JS, Kim H, Lee WJ, Kim BR. Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas suggesting malignant potential. Pancreas. 2006; 32:276–280. PMID: 16628083.

15. Shimizu M, Matsumoto T, Hirokawa M, Monobe Y, Iwamoto S, Tsunoda T, et al. Solid-pseudopapillary carcinoma of the pancreas. Pathol Int. 1999; 49:231–234. PMID: 10338079.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download