Abstract

Purpose

To determine the superior chemotherapeutic regimen between monthly 5-FU plus cisplatin (FP) and weekly cisplatin alone in concurrent chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer, the compliance of treatment, response, survival and toxicities were analyzed between the two arms.

Materials and Methods

Between March 1998 and December 2001, 61 patients with locally advanced cervical cancer (stage IIB through IVA) and negative para-aortic lymph nodes were randomly assigned to either 'monthly FP' (arm I, n=34) or 'weekly cisplatin' (arm II, n=27) with concurrent radiotherapy. The patients of arm I received FP (5-FU 1,000 mg/m2/day + cisplatin 20 mg/m2/day, for 5 days, for 3 cycles at 4 week intervals) and those of arm II received cisplatin (30 mg/m2/day, for 6 cycles at 1 week intervals) with concurrent radiotherapy. The radiotherapy consisted of 41.4~50.4 Gy external beam irradiation in 23~28 fractions to the whole pelvis, with high dose rate brachytherapy delivering a dose of 30~35 Gy in 6~7 fractions to point A. During the brachytherapy, a parametrial boost was delivered. The median follow-up period for survivors was 44 months.

Results

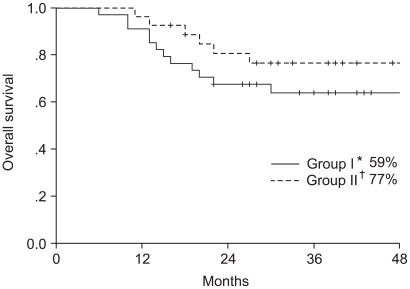

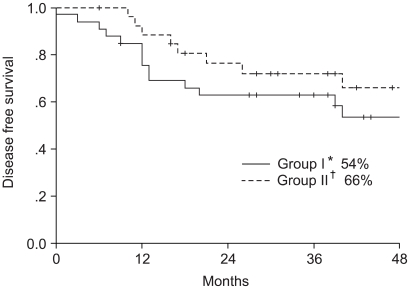

The compliance of treatment in monthly FP weekly cisplatin arms were 62 and 81%, respectively. The complete response rates at 3 months were 96 and 88% in arms I and II, respectively. The 4-year overall survival and disease free survival rates were 64 and 54% in the arm I and 77 and 66% in the arm II, respectively. The incidence of hematologic toxicity more than grade 2 was 29% in the arm I and 15% in the arm II. Only one patient in arm I experienced grade 3 gastrointestinal toxicity. No severe genitourinary toxicity was observed.

Uterine cervical cancer is the fifth most common malignant disease in Korean women, accounting for 9.1% of total malignancies according to the Korean statistics in 2002. Surgery or radiotherapy, when used in the treatment of the early cervical cancer of stage IIA or less, provide similar clinical outcomes. Five-year disease free survival rates of 80~90% and 70~80% were reported in stage IB and IIA carcinomas of the cervix, respectively (1). Although radiotherapy has been widely used in the treatment of locally advanced cervical cancer, radiotherapy alone resulted in treatment failure in 20~50% patients with stage IIB and 50~75% of those with stage IIIB or higher stage (2). It is well known that the treatment failure mainly developed within 3 years after radiotherapy, with many of the local recurrences developing in the parametrium (3).

To increase the local control rate of locally advanced cervical cancer, the concurrent use of radiosensitizers, such as misonidazole, hydroxyurea, cisplatin and 5-FU with radiation therapies, have been studied (4~6). Improved local control and survival rates were reported with the use of concurrent chemoradiation using cisplatin and/or 5-FU due to their direct cytotoxicity as well as radiosensitization. Prospective randomized trials published in the early 1990's proved that sequential chemoradiotherapy was unable to achieve more favorable outcomes in local control and survival due to the greater toxicities over that of radiation alone (7~9). In 1999, Morris et al. through a prospective randomized study, reported more favorable results in patients with concurrent chemoradiation using cisplatin plus 5-FU than with radiotherapy alone (10). During the same period, other multi-institutional randomized controlled trials revealed increased survival rate with the use of cisplatin based concurrent chemoradiotherapy (11,12). The findings of these trials prompted the US National Cancer Institute to recommend concurrent cisplatin based chemoradiotherapy as the treatment for cervical cancer (13), but no consensus on the optimal dose and regimen of chemotherapeutic agents has been developed. Moreover, the role of 5-FU administered concurrently with cisplatin is unclear as no randomized trial between cisplatin alone vs. cisplatin plus 5-FU has been conducted.

We conducted a prospective randomized clinical trial to compare monthly 5-FU plus cisplatin to weekly cisplatin alone, both with concurrent radiotherapy, for locally advanced cervical cancer. Through this study, it is hoped a more optimal regimen for the concurrent chemoradiotherapy of locally advanced cervical cancer can be developed.

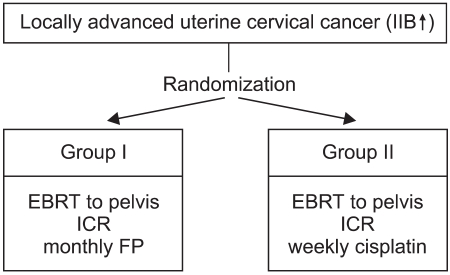

Between March 1998 and December 2001, 61 patients with pathologically confirmed, clinically diagnosed FIGO (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) stage IIB to IVA uterine cervical cancer were entered into this clinical trial. For exact staging, all 61 patients received a physical examination, CBC, liver function test, urine analysis, chest X-ray, IVP, cystoscopy, sigmoidoscopy and pelvic MRI or CT scanning. Eligible patients had to have a Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance scale ≤2, age ≥18 years, adequate hepatic, renal and bone marrow functions for treatment (serum total bilirubin <1.5 mg/dl, AST/ALT <3 folds of normal, serum creatinine <1.5 mg/dl or creatinine clearance >50 ml/min, WBC >4,000/µl, platelet >100,000/µl, hemoglobin >10 gm/dl), a negative para-aortic lymph node status on radiological examination, and no history of prior chemotherapy and radiotherapy. All selected patients were intended for definitive chemoradiation treatment. The patients were allocated to one of two treatment arms, using random numbers table, and stratified by stage at the time of consultation. The patients of both treatment arms were received external beam radiotherapy to the whole pelvis, with intracavitary radiation. Meanwhile, 34 patients were administered FP (5-FU + cisplatin) regimen chemotherapy at 4-week intervals; all others received weekly cisplatin (Fig 1). The informed consent of the patients and approval of the committee of clinical trial of Asan Medical Center were obtained.

All patients were treated with a four-field box technique (AP-PA and two laterals field). The radiation field encompassed a volume that included the whole uterus, the primary mass, the paracervical, parametrial and uterosacral regions, as well as the external iliac, hypogastric and obturator lymph nodes. The AP/PA field extended 1.5 to 2 cm laterally to the widest bony margin of the true pelvis. The superior border of the field was the mid-point of L5, and the inferior border included a 2 cm margin from the lowest extension of the primary tumor or lower portion of obturator foramen. The anterior border of the lateral fields was the anterior one third of symphysis pubis, and the posterior border was usually the S2-S3 interface based on the extent of the primary tumor. The treatments were designed with the use of computerized radiation dosimetry, delivered with 15-MV X rays from a linear accelerator (Varian Clinac 1800, 2100 C/D) to the whole pelvis, without midline shielding. Twenty-three fractions of 1.8 Gy were delivered to a total dose of 41.4 Gy in patients with stage IIB cervix cancer, and 50.4 Gy, in 28 fractions, in patients with stage IIIA or higher stage. After external beam irradiation, intracavitary radiotherapy, using an Ir-192 high dose rate brachytherapy unit (microSelectron®, Nucletron, the Netherlands), was performed three times a week (Monday, Wednesday and Friday). Thirty-five Gy, in 7 fractions, to point A were delivered to patients with stage IIB and 30 Gy, in 6 fractions, to patients with IIIA or higher stage. During the brachytherapy, a parametrial boost using external beam radiation was delivered, with conventional fractionation, up to 65 Gy to the thickened parametrium and 60 Gy to the normal parametrium, twice a week (Tuesday and Thursday). Intracavitary radiotherapy and a parametrial boost were not delivered on the same day.

From the first treatment day, 5-FU and cisplatin were given as i.v. infusions at doses of 1,000 and 20 mg/m2/day, respectively, for 5 consecutive days in 3 cycles at 28 day intervals to the patients randomized into the FP regimen. In the weekly cisplatin arm, 30 mg/m2 of cisplatin was administered as an i.v. injection in 6 cycles at 7 day intervals. Once a week during radiotherapy, or before the initiation of chemotherapy, CBC, liver function and renal function tests were conducted. In the case of an absolute neutrophil count less than 1,000/mm3 or a platelet count less than 100,000/mm3; the chemoradiotherapy was delayed until recovery.

The treatment related acute toxicities were assessed based on the history, physical examination and CBC, according to the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) criteria for acute toxicities. The response to treatment was evaluated using both pelvis MRI and physical examination at 3 months after the completion of treatment. A complete response was defined as the disappearance of the gross tumor either clinically or radiologically (using follow up pelvic MRI at 3 months). A partial response was defined as more than a 50% reduction of the tumor volume either clinically or radiologically.

After radiotherapy, the patients were evaluated at 1 and 3-month intervals for the first 2 years, and every 6 months thereafter. The median follow up period of the 43 survivors was 44 months. Local recurrence and distant metastasis were defined as any recurrence within and outside of the radiation field, respectively. The first site of recurrence was recognized when local and distant metastasis occurred together. The survival time was counted from the date of randomization to that of recurrence diagnosis, death or last follow-up. Patients were censored if they were disease-free at the last contact (or died without disease) in the disease free survival analysis. However; death, regardless of final status, was counted as an event in the survival analysis. The primary end point was compliance to treatment. Previous studies on concurrent chemoradiotherapy have shown compliance rates between 70~80% (10~12). Therefore, a sample size of 112 patients per group was calculated on the basis of an ability to detect a 15% difference between the regimens, with a statistical power of 80% using a two-sided significance level of 0.05. Interim analysis was scheduled to occur when one third of the patients had been enrolled and followed-up for more than 3 years. Statistical analyses were carried out using the SPSS version 10.0 statistical package (Chicago, IL). The Kaplan-Meier method was used to construct curves for the relapse-free and overall survival. The log-rank test was used to compare treatments and for univariate analyses. The Chi-Squared test was used to compare the recurrence and complication rates between the two arms. All p values were two-sided.

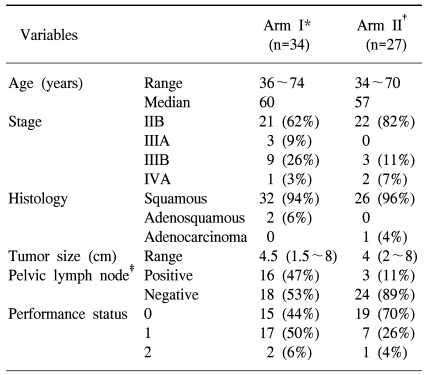

The study group was comprised of 34 patients in arm I and 27 in arm II, with a median age of 58 years (36~74 in arm I, 34~70 in arm II). The extent of disease was ranked as either: IIB, IIIA, IIIB or IVA, with FIGO stage in 21, 3, 9 and 1 in arm I, and 22, 0, 3 and 2 in arm II, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference in age and stage distribution. Most had a squamous cell carcinoma, but 2 patients in arm I had an adenosquamous carcinoma and 1 in arm II had an adenocarcinoma. There were also no differences in the performance stati, tumor sizes and total treatment times between the two arms, with the exception of pelvic lymph node involvement (Table 1).

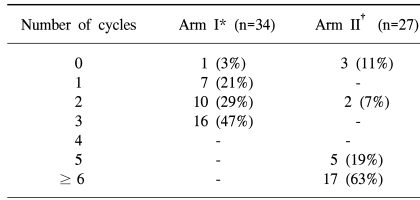

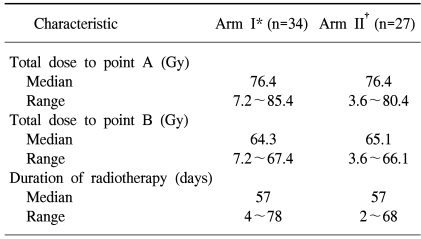

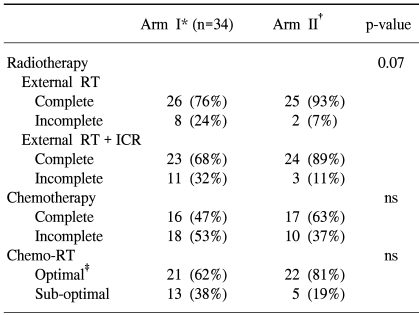

One and 3 patients in arms I and II did not receive chemotherapy. Table 2 shows the number of cycles of chemotherapy received in both arms. Chemotherapy was interrupted in the patient of arm I due to autoimmune hepatitis and due to poor performance stati in the 3 from arm II. The median dose to point A was 76.4 Gy in both arms and the median doses to point B were similar between the two arms (Table 3). The median total treatment time was 57 days in both arms (Table 3). The completion of radiotherapy in the monthly FP arm was lower than in the weekly cisplatin arm (68 vs. 89%). The difference between both arms was marginally statistically significant (p=0.07). Four patients did not undergo brachytherapy after completion of the external radiotherapy (3 patients in arm I and 1 in arm II). Concurrent Chemoradiation therapy was delivered according to protocol in 62 and 81% of the patient in the monthly FP and weekly cisplatin arms, respectively (Table 4).

The response to treatment and patterns of failure were evaluated 3 months after treatment using physical examination including pelvic examination and pelvic MRI. Twenty two of the 23 patients (96%) in the arm I who had received planned chemoradiotherapy showed a complete response and the other a partial response. In the arm II, 22 of the 25 patients (88%) showed a complete response and the 3 others a partial response. No significant difference was observed.

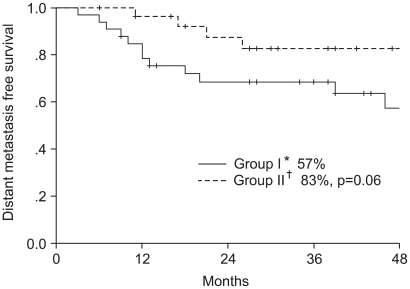

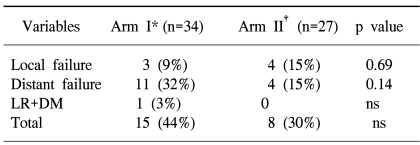

Three patients (9%) in the monthly FP arm and 4 (15%) in the weekly cisplatin arm had a local recurrence. Distant metastasis occurred in 11 patients (32%), including one case with a relapse, in arm I and in 4 (15%) in arm II during the follow up period. More distant metastases were observed in the arm I, but this difference did not reach statistical significance (Table 5).

The study included 61 patients, with a median follow up period of 26 months (range: 6~56 months). The median follow up period of the survivors was 32 months. When all 61 patients were analyzed according to intention to treat, the 4-year overall survival and disease free survival rates were 70 and 59%, respectively; 64 and 54% in the arm I and 77 and 66% in the arm II, respectively (Fig. 2, 3), but with no significant difference. The 4-year distant metastasis free survival rate of arm I was 57%, which was marginally inferior to the 83% of arm II (p-value: 0.06, Fig. 4).

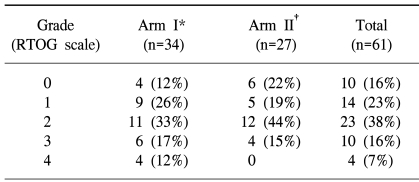

The acute hematological, gastrointestinal (GI) and genitourinary (GU) toxicities were evaluated using the RTOG acute toxicity criteria. Grade 2 hematological toxicity was most frequently observed; 11 (33%) patients in arm I and 12 (44%) in arm II (Table 6). Severe hematological toxicities greater than grade 2 were observed in 10 (29%) and 4 (15%) patients in arms I and II, respectively. Among the GI toxicities, nausea and vomiting were the most frequently reported. Grade 2 toxicity requiring medication was observed in 18 (53%) and 13 (48%) patients in arms I and II, respectively. Only 1 patient in the arm I had grade 3 GI toxicity. Most occurrences of toxicity were controlled with supportive care. No severe GU toxicity greater than grade 2 was observed, but 3 patients in each arm had grade 2 GU toxicity. With regard to late complications, one patient in the arm I had symptoms compatible with radiation cystitis, and 3 in the arm II reported symptoms compatible with radiation enteritis, but these were controlled with supportive treatment. There were no differences in the hematological, GI and GU toxicities between the two arms.

Concurrent chemoradiotherapy has the theoretical advantages of avoiding any delay in the initiation of radiotherapy, which is the main treatment modality, shortening the overall treatment time, preventing repopulation of the tumor and cross resistance to therapy, as well as radiosensitizing the effect of chemotherapeutic agents compared with neoadjuvant therapy (14,15). Concurrent chemoradiation has been proved to achieve more favorable clinical outcome in many organs, including bladder, head and neck malignancies (16,17). With concurrent chemoradiation treatment of uterine cervical cancer, cisplatin, 5-FU and hydroxyurea have been commonly investigated (10~12,18). Recently, the results of five multi-institutional randomized controlled trials demonstrated a survival benefit for the concurrent cisplatin-based chemoradiotherapy in the treatment of cervical cancer (10~12,18,19). Three of these studies dealt with the definitive treatment of locally advanced cervical cancer (10~12).

However, these results should be interpreted with caution. In the studies of Whitney et al. (12) and Rose et al. (11), the control arm received pelvic radiotherapy and hydroxyurea. The two trials included only patients with a surgically confirmed para-aortic lymph node negative status. Although, they had weak points; the median overall treatment time was prolonged over 9 weeks and an insufficient dose, less than 80 Gy to A point, was delivered. It is well known that a prolonged total treatment time is related to reductions of local control, survival rates (20~22) and dose-response relationships (23). The two studies mentioned above can be criticized as the insufficiencies in the radiation treatment magnified the apparent benefit of the chemotherapy. Therefore, an overall treatment time of less than 55 days and a dose of 85~90 Gy to A point are recommended. In contrast to the studies mentioned above, the overall treatment time and radiation dose were relatively sufficient in the trial of Morris et al. (10). However, one third of patients had a stage IIA or less disease, but survival benefits were proved only for those with stage IB to IIB diseases. Thus, it can be concluded that the concurrent chemoradiotherapy resulted in increased survival only in certain groups of patients.

The overall survival and disease free survival rates of the current study are similar to those of other studies (10~12). Considering the surgical confirmation of the paraaortic lymph node status in other studies (11,12), our study have shown the most favorable results to date. However, further analysis will be required due to our short follow up period.

Less than 10, 20 and 10% of severe hematological, GI and GU toxicities have been reported when 20 and 1,000 mg/m2/day of cisplatin and 5-FU, respectively, were used concurrently with radiotherapy prior to definitive surgery (24). It was also reported that a significantly higher Grade 4 toxicity, 23%, was achieved in the concurrent chemoradiotherapy arm with 50 mg/m2 of cisplatin and 750 mg/m2/day of 5-FU than the radiotherapy alone (25). Morris et al. (10) used 75 and 1,000 mg/m2/day of cisplatin and 5-FU, respectively, for 5 days in each cycle, and Rose et al. (11) and Whitney et al. (12) used 50 and 1,000 mg/m2/day for 4 days in each cycle. In our study, cisplatin combined with 5-FU was used for 5 days from the first day of treatment, so 100 mg/m2 of cisplatin and 5,000 mg/m2 of 5-FU per each cycle were administered. The dose of chemotherapeutic agents might be related to the lower compliance rate of patients in arm I, although statistical significance could not be reached. The reason distant metastases were commonly observed in arm I (p=0.06) might be due to the lower compliance rate among these patients.

Our study also had some drawbacks; the small sample size and short follow up period. The survival rate, acute and chronic toxicities, patterns of failure as well as prognostic factors will also be analyzed. Although randomized using the random numbers table, more patients were allocated to arm I at the time of analysis. Also, more patients with pelvic lymph node were randomized to arm I. It is anticipate that a greater number of enrolled cases will solve these problems. The role of 5-FU, combined with cisplatin, will also be defined through additional studies.

The difference in the survival and patterns of failure between the patients receiving complete and incomplete FP chemotherapies will be analyzed to define the role of chemotherapeutic agents after radiotherapy, as chemotherapy in the treatment of cervical cancer acts mainly as a radiosensitizer.

There were no significant differences in the response to treatment, patterns of failure, survival rate and toxicities between the monthly FP and weekly cisplatin arms, with the exception of compliance. The compliance of chemotherapy was similar in both arms. However, the patients that received weekly cisplatin chemotherapy experienced higher completion of radiation therapy. We suggest that the cisplatin alone regimen is at least equally effective and well tolerated compared to the FP regimen for the treatment of locally advanced cervical cancer. Moreover, the cisplatin alone regimen has the advantage of not requiring hospitalization. However, more patients and a longer follow up period will be needed to evaluate which of the monthly FP or weekly cisplatin regimens is better.

References

1. Gonzalez DG, Ketting BW, Bunningen BV, Dijk JD. Carcinoma of the uterine cervix stage IB and IIA: result of postoperative irradiation in patients with microscopic infiltration in the parametrium and/or lymph node metastasis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989; 16:389–395. PMID: 2921143.

2. Coia L, Won M, Lanciano R, Marcial VA, Martz K, Hanks G. The patterns of care outcome study for cancer of the uterine cancer: Results of the second national practice survey. Cancer. 1990; 66:2451–2456. PMID: 2249184.

3. Jampolis S, Andras EJ, Fletcher GH. Analysis of sites and causes of failures of irradiation in invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the intact uterine cervix. Radiology. 1975; 115:681–685. PMID: 1129485.

4. Leibel S, Bauer M, Wasserman T, Marcial V, Rotman M, Hornback N, et al. Radiotherapy with or without misonidazole in patients with stage IIIB or IVA squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix: preliminary report of a radiation therapy oncology group randomized trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1987; 13:541–549. PMID: 3104249.

5. Piver MS, Barlow JJ, Vongtama V, Blumenson L. Hydroxyurea: a radiation potentiator in carcinoma of the uterine cervix. A randomized double-blind study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1983; 147:803–808. PMID: 6359885.

6. Dewit L. Combined treatment of radiation and cisdiaminedichloroplatinum (II): a review of experimental and clinical data. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1987; 13:403–426. PMID: 3549645.

7. Tattersall MH, Lorvidhaya V, Vootiprux V, Cheirsilpa A, Wong F, Azhar T, et al. Randomized trial of epirubicin and cisplatin chemotherapy followed by pelvic radiation in locally advanced cervical cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1995; 13:444–451. PMID: 7844607.

8. Kumar L, Kaushal R, Nandy M, Biswal BM, Kumar S, Kriplani A, et al. Chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone in locally advanced cervical cancer: a randomized study. Gynecol Oncol. 1994; 54:307–315. PMID: 7522200.

9. Souhami L, Gil RA, Allan SE, Canary PC, Araujo CM, Pinto LH, et al. A randomized trial of chemotherapy followed by pelvic radiation therapy in stage IIIB carcinoma of the cervix. J Clin Oncol. 1991; 9:970–977. PMID: 1709686.

10. Morris M, Eifel PJ, Lu J, Grigsby PW, Levenback C, Stevens RE, et al. Pelvic radiation with concurrent chemotherapy compared with pelvic and para-aortic radiation for high-risk cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999; 340:1137–1143. PMID: 10202164.

11. Rose PG, Bundy BN, Watkins EB, Thigpen JT, Deppe G, Maiman MA, et al. Concurrent cisplatin-based radiotherapy and chemotherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999; 340:1144–1153. PMID: 10202165.

12. Whitney CW, Sause W, Bundy BN, Malfetano JH, Hannigan EV, Fowler WC Jr, et al. Randomized comparison of fluorouracil plus cisplatin versus hydroxyurea as an adjuvant to radiation therapy in stage IIB-IVA carcinoma of the cervix with negative para-aortic lymph nodes: a Gynecologic Oncology Group and Southwest Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 1999; 17:1339–1348. PMID: 10334517.

13. National Cancer Institute. Concurrent chemoradiation for cervical cancer. Clinical announcement. 1999. 2.

14. Perez CZ, Grigsby PW, Chao CKS. Chemotherapy and irradiation in locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix: A review. Semin Radiat Oncol. 1997; 7(Supple 2):45–65.

15. Fu KK. Biological basis for the interaction of chemotherapeutic agents and radiation therapy. Cancer. 1985; 55(9 Suppl):2123–2130. PMID: 3884135.

16. Pignon JP, Bourhis J, Domenge C, Designe L. Chemotherapy added to locoregional treatment for head and neck squamous-cell carcinoma: three meta-analyses of updated individual data. Lancet. 2000; 355:949–955. PMID: 10768432.

17. Eapen L, Stewart D, Danjoux C, Genest P, Futter N, Moors D, et al. Intraarterial cisplatin and concurrent radiation for locally advanced bladder cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1989; 7:230–235. PMID: 2915239.

18. Keys HM, Bundy BN, Stehman FB, Muderspach LI, Chafe WE, Suggs CL, et al. Cisplatin, radiation, and adjuvant hysterectomy compared with radiation and adjuvant hysterectomy for bulky stage IB cervical carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1999; 340:1154–1161. PMID: 10202166.

19. Peters WA, Liu PY, Barrett RJ, Barrett R, Gordon W, Stock R, et al. Cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil plus radiation therapy are superior to radiation therapy as adjunctive in high-risk early-stage carcinoma of the cervix after radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy: Report of a phase III intergroup study. Gynecol Oncol. 1999; 72:443–527. PMID: 10053123.

20. Fyles A, Keane TJ, Barton M, Simm J. The effect of treatment duration in the local control of cervix cancer. Radiother Oncol. 1992; 25:273–279. PMID: 1480773.

21. Lanciano RM, Pajak TF, Martz K, Hanks GE. The influence of treatment time on outcome for squamous cell cancer of the uterine cervix treated with radiation: a patterns-of-care study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993; 25:391–397. PMID: 8436516.

22. Petereit DG, Sarkaria JN, Chappell R, Fowler JF, Hartmann TJ, Kinsella TJ, et al. The adverse effect of treatment prolongation in cervical carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995; 32:1301–1307. PMID: 7635769.

23. Choy D, Wong LC, Sham J, Ngan HY, Ma HK. Dose-tumor response of carcinoma of cervix: an analysis of 594 patients treated by radiotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 1993; 49:311–317. PMID: 8314532.

24. Jurado M, Monge RM, Foncillas JG, Azinovic I, Aristu J, Garcia GL, et al. Pilot study of concurrent cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil, and external beam radiotherapy prior to radical surgery +/- intraoperative electron beam radiotherapy in locally advanced cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1999; 74:30–37. PMID: 10385548.

25. Grigsby PW, Graham MV, Perez CA, Galakatos AE, Camel HM, Kao MS. Prospective phase III studies of definitive irradiation and chemotherapy for advanced gynecologic malignancies. Am J Clin Oncol. 1996; 19:1–6. PMID: 8554027.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download