Abstract

Purpose

The surgical caseload or duration of practice of a surgeon may influence the outcomes of gastric cancer surgery. This study aimed to clarify the surgical quality provided by specialized gastric cancer surgeons.

Materials and Methods

The postoperative courses of 1,877 patients who underwent surgery for gastric cancer were retrospectively reviewed. For classification of the surgeon's expertise, the number of yearly resections performed by, and consecutive years of practice of, the surgeons were used. The outcome measures used were the 30-day mortality and long-term survival.

Results

Surgical mortalities of patients who underwent surgery by a specialized surgeon and those by a general surgeon revealed no statistically significant difference. A significant difference in the five-year survival rates was found with surgeons with at least two consecutive years of practice compared to those with less than two years, when 50 or more cases had been conducted per year (63.9% and 59.7%; p=0.0380). In cases of four-years of consecutive practice, the five-year survival rate was significantly improved, even if only 10 cases were performed annually (64.9% and 58.3%; p=0.0023), although the best survival rate was found with surgeons that had performed 50 or more surgeries per year.

Conclusion

Improved survival rates, with acceptable surgical mortality, can be achieved for gastric cancer when the surgery is performed by a specialized surgeon. A specialized gastric cancer surgeon can be defined as one who has operated on more than 50 new cases per year, with 2 or more consecutive years of surgical practice.

The technical skills of a surgeon may influence the outcomes of cancer surgery. The case volume has been suggested as an indicator of the surgical quality of individual surgeons (1,2), and the performance of cancer surgery by high-volume surgeons may lead to improved outcomes.

Hillner et al. (3) found extensive, consistent literature to support a volume-outcome relationship for cancers treated with technologically complex surgical procedures, such as most intra-abdominal and lung cancers. For example, a considerable improvement in overall survival can be achieved when the surgery is undertaken by surgeons with a special interest in colorectal surgery or surgical oncology (4). The outcome can also be improved with both colorectal surgical subspecialty training and a higher frequency of rectal cancer surgery (2,5). Therefore, the surgeon is regarded as an important prognostic factor in the treatment of colorectal cancer (6). For breast cancer, a British study found that physician specialty and volume were associated with improved long-term outcomes (7). However, Gillison et al. (8) reviewed the medical records of 1,125 patients who had undergone surgery for cardio- oesophageal cancer, but failed to identify a clear improvement in the surgical outcome with increasing annual surgeon workload.

Some studies have focused on the relationship between short-term outcomes, such as postoperative mortality and morbidity, and surgeon-related variability, mainly with respect to case volume (1,4,9~11).

Although the incidence of gastric cancer has declined in Western countries, it is one of the most frequently occurring malignancies in the world; in some Eastern countries it is even the most frequent malignancy. Similarly to other major cancer surgery, the surgical caseload or a surgeon's duration of practice may also influence the outcome of gastric cancer surgery. It seems that a certain caseload volume is necessary for good results, but above this level, the inter-surgeon variability in surgical outcomes can not be correlated with the caseload volume (1). However, the effect of specific surgeon-related factors on the outcome of gastric cancer surgery is still largely unknown.

This study aimed to clarify the specialized surgeon's standards based on the extent of surgical experiences during the course of a surgeon's practice, and the surgical quality provided by the specialized gastric cancer surgeon.

Between 1985 and 1997, 1,877 patients with biopsy proven gastric cancer underwent surgery at the Department of Surgery, Kyungpook National University Hospital. There were 638 women and 1,239 men with a median age of 56, ranging from 19 to 84 years. According to the tumor node metastasis (TNM) classification (12), 413 patients had stage IA, 341 stage IB, 304 stage II, 298 stage IIIA, 192 stage IIIB and 329 stage IV diseases. These patients had undergone a gastrectomy by one of eight surgeons.

The surgeon's expertise, a general surgeon or a specialized surgeon, was classified according to the number of yearly resections performed and the number of consecutive years of practice. The annual operations performed by a surgeon was divided into 10, 20, 30, 40 and ~50 or more cases, which were divided into further groups according to the number of consecutive years of surgical practice; one, two, three, four and more than four consecutive years. Finally, a combined analysis was made of a surgeon's annual cases and the number of consecutive years of surgery (cases-years category).

The survival for all discharged patients was calculated from the date of operation until death or the last follow-up, and Kaplan-Meier survival curves were plotted and compared using the log-rank test, according to the cases-years category and other well-known prognostic factors. A multivariate analysis for the outcomes of the gastrectomies was performed using a Cox proportional hazards model. The proportions of patients with a given characteristic were compared by the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. Differences in the means of continuous measurements were tested using the Student's t-test. The differences were judged to be significant with a p-value of less than 0.05.

Of the 1,877 patients, 84 were lost to follow-up (follow-up rate, 95.5%).

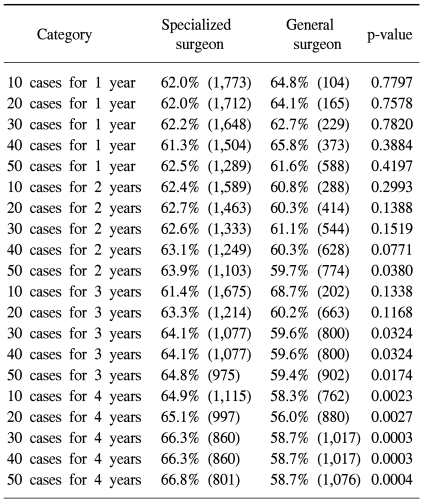

The 5-year survival rates were compared, based on the cases-years category, with the results summarized in Table 1. A significant difference in the survival rate was found for surgeons with at least two years practice, compared to those with less, when 50 or more annual cases had been conducted (63.9% and 59.7%; p=0.0380). When a surgeon had performed surgery for more than three consecutive years, the survival rate was significantly improved, even with only 30 cases operated annually (64.1% and 59.6%; p=0.0324). In the case of four consecutive years of performance, the rate markedly improved, even with only 10 cases operated annually (64.9% and 58.3%; p=0.0023). The difference in 5-year survival rate showed the greatest improvement for surgeons performing more than 50 annual cases, who had also been in practice for 4 consecutive years.

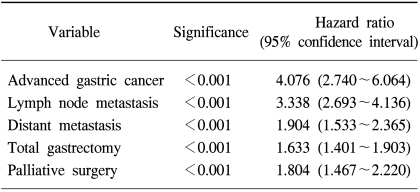

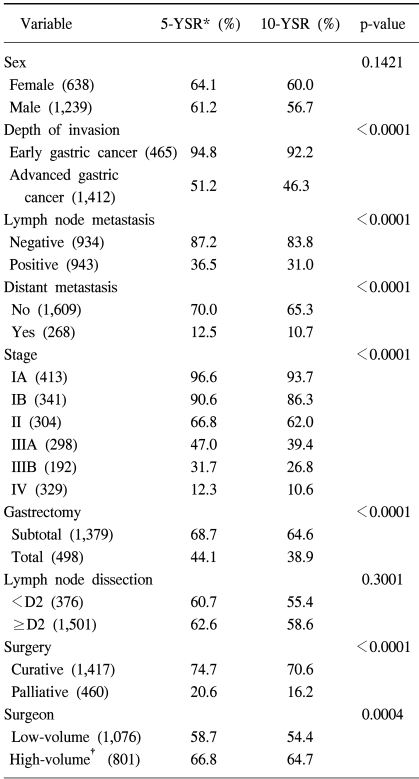

Table 2 shows the results from the univariate analyses for factors associated with the postoperative survival rates. From these analyses, advanced gastric cancer, lymph node metastasis, distant metastasis, advanced stage, total gastrectomy, palliative surgery and low-caseload volume surgeons were significantly associated with lower survival rates; however, none of the cases-years categories were revealed to be an independent prognostic factor. Even the category revealing the largest difference in the survival rate (50 cases for 4 years) was not significant from the multivariate analysis (Table 3).

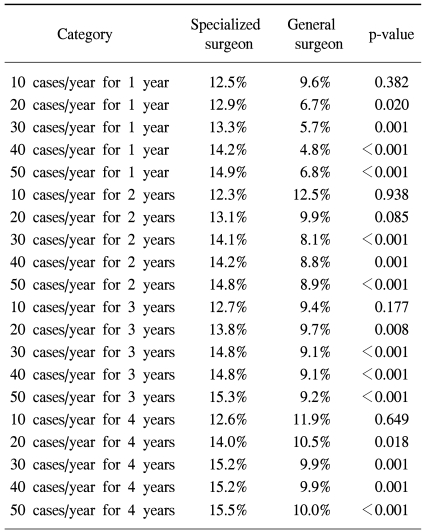

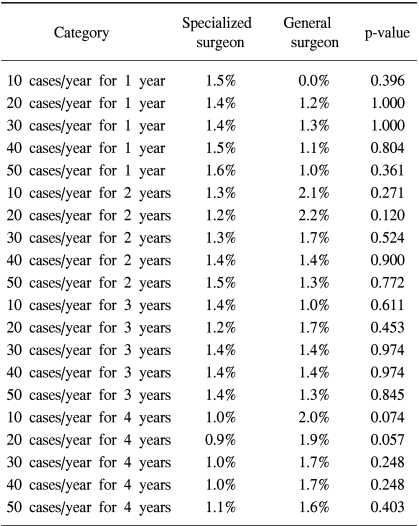

Major morbidity tended to increase with caseload volume and duration of practice (Table 4), but no statistically significant difference was revealed in the postoperative 30-day mortalities of patients who had undergone surgery by a specialized surgeon compared to those by a general surgeon (Table 5).

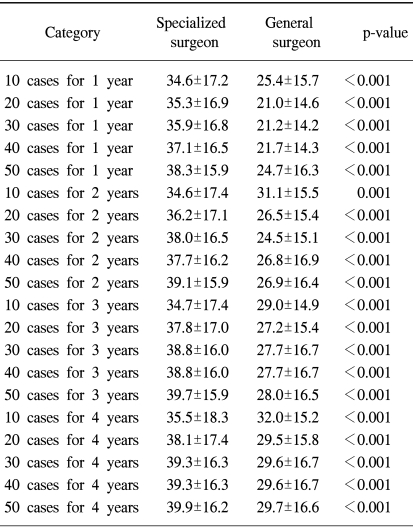

The mean number of dissected lymph nodes was greater by a specialized surgeon than that by a general surgeon (Table 6).

Statistical and clinical differences between reports of surgical therapy are usually ascribed to differences in the named method of treatment. However, it is becoming clear that surgeons vary in their ability to produce a given result; this phenomenon is sometimes referred to as "surgeon-related variability." Thus, surgical treatment should be seen as the resultant vector of the named procedure plus the effect of the surgeon-related variability (13).

Many investigators have used case volume as an indicator of a surgeon's ability. There is a group of surgeons that perform only a limited number of operations. In this group, the long-term results may be worse than those achieved by surgeons with a higher caseload volume. Martling et al. (5) regarded surgeons who performed more than 12 resections for rectal cancer per year as high-volume surgeons. Stocchi et al. (14) found that surgeons treating more than 10 rectal cancer cases had lower local recurrence rates than those treating 10 or less annual cases. With regard to resections for carcinomas of the esophagus and cardia, Gillison et al. (8) arbitrarily divided surgeons into three groups: an infrequent operation group, in which surgeons performed fewer than four resections per year, an intermediate operation group, between four and 11 resections per year and a frequent operation group, 12 or more resections per year. Surgeons treating less than 30 new cases of breast cancer per year revealed poor survivals (7). In a Japanese report (15), the five-year survival rate after a typical D2 gastrectomy was found to be independent of the experience of the surgeon. However, McCulloch (16) found that surgeons needed to perform at least 30 dissections before the survival rates reached a plateau.

Parikh et al. (17) suggested a learning curve, lasting between 18 to 24 months or 15 to 25 procedures, before the survival rates reached a plateau. It seems that not only the individual surgeon's caseload volume, but also the duration of practice, is needed to maintain high standards of surgical quality. Therefore, a combined analysis of a surgeon's annual caseload and consecutive years of practice (cases-years category) was used in this study. In the case of four consecutive years of performance, although there was a statistically significant difference in the five-year survival rate, even for surgeons that had performed only 10 cases annually, the best five-year survival rate were achieved by surgeons who performed 50 or more cases per year. For surgeons who had performed surgeries for more than three consecutive years, 30 operative cases per year were needed to obtain a better survival rate. A significant difference in the survival rate was found for surgeons having gained at least two years of practice, when 50 or more cases had been conducted. Therefore, it can be suggested that the learning period of surgery for gastric cancer is two years, with 50 cases conducted annually. Conversely, the survival rate can be improved with at least a 10 case annual caseload volume, with 4 consecutive years of practice. However, the learning period for every surgeon will differ, as there will always be quick and slow learners. Therefore, the number of operations or period needed for a plateau in the survival rate to be reached for a certain procedure will differ between surgeons; the method of learning may also influence the survival rate. Supervision and training are likely to lead to more effective learning of a given procedure than the situation where the surgeon is self-taught (18).

Quality control is of utmost importance in surgical trials. Recently, two large randomized multicenter studies, comparing D1 and D2 dissections, have been published: the Dutch Gastric Cancer Trial (19,20) and the British Medical Research Council Gastric Cancer Surgical Trial (21,22). Both studies revealed there was no 5-year survival advantage for a D2 over a D1 dissection, and concluded that there was no support for the standard use of D2 lymph node dissections in Western patients with gastric cancer. However, in the reports from the Netherlands, 11 supervising surgeons attended to 996 patients at 80 hospitals over a 4 year period. Of these 996 patients, a D2 dissection was performed in 331 cases. This means that only three patients were managed per hospital per year, with supervising surgeons attending to less than 10 D2 dissection cases per year. The British trial was conducted on 32 surgeons who performed 200 D2 dissection cases. Therefore, the results of theses trials may not be justifiable because the quality of surgery is uncontrolled due to the low caseload volume.

The survival rate for women was reported to be higher than that for men in a study based on a large population-based series (23), but another report suggested a lower survival rate for women (24). In our study, no significant survival difference was identified between men and women, although there was a tendency toward a lower survival rate for men. The anatomical extent of gastric cancer (12), the depth of invasion, status of regional lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis, were significant prognostic factors in the univariate and multivariate analyses. A curative resection produces a chance of cure; whereas, survival was found to be very poor following a non-curative resection. As with the report of Roder et al. (25), our study also revealed a curative resection as an independent prognostic factor.

Some studies showed a correlation between postoperative mortality or morbidity and a surgeon's caseload volume (9,10). However, other studies reported that short-term outcomes showed no association with the caseload volume (4,11). The greater number of lymph nodes dissected by specialized compared to general surgeons implies that specialized surgeons tend to dissect lymph nodes more widely, which might be responsible for increased morbidity. However, the beneficial effect of wider lymph node dissection was obscure as about half our cases had no regional lymph nodes metastasis. The mortality of patients who underwent surgery by a specialized surgeon compared to that by a general surgeon revealed no statistically significant difference. This similar mortality can be explained by the better management provided by the specialized surgeons due to their increased experience of complicated cases.

Although no cases-years category was found to be an independent prognostic factor from the multivariate analyses, a trend toward improved survival and reasonable postoperative mortality was identified when the surgery was performed by a specialized surgeon. A specialized gastric cancer surgeon can be defined as one who has operates on more than 50 new cases per year, with 2 or more consecutive years of surgical practice.

Improved survival rates, with acceptable surgical mortality, can be achieved when surgery for gastric cancer is performed by a specialized surgeon. A specialized gastric cancer surgeon can be defined as one who has operated on more than 50 new cases per year, with 2 or more consecutive years of surgical practice.

References

1. Hermanek P, Hohenberger W. The importance of volume in colorectal cancer surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1996; 22:213–215. PMID: 8654598.

2. Porter GA, Soskolne CL, Yakimets WW, Newman SC. Surgeon-related factors and outcome in rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 1998; 227:157–167. PMID: 9488510.

3. Hillner BE, Smith TJ, Desch CE. Hospital and physician volume or specialization and outcomes in cancer treatment: importance in quality of cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2000; 18:2327–2340. PMID: 10829054.

4. McArdle CS, Hole D. Impact of variability among surgeons on postoperative morbidity and mortality and ultimate survival. BMJ. 1991; 302:1501–1505. PMID: 1713087.

5. Martling A, Cedermark B, Johansson H, Rutqvist LE, Holm T. The surgeon as a prognostic factor after the introduction of total mesorectal excision in the treatment of rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2002; 89:1008–1013. PMID: 12153626.

6. Meagher AP. Colorectal cancer: is the surgeon a prognostic factor? A systematic review. Med J Aust. 1999; 171:308–310. PMID: 10560448.

7. Sainsbury R, Haward B, Rider L, Johnston C, Round C. Influence of clinician workload and patterns of treatment on survival from breast cancer. Lancet. 1995; 345:1265–1270. PMID: 7746056.

8. Gillison EW, Powell J, McConkey CC, Spychal RT. Surgical workload and outcome after resection for carcinoma of the oesophagus and cardia. Br J Surg. 2002; 89:344–348. PMID: 11872061.

9. Edge SB, Schmieg RE, Rosenlof LK, Wilhelm MC. Pancreas cancer resection outcome in American University centers in 1989-1990. Cancer. 1993; 71:3502–3508. PMID: 8098265.

10. Munoz E, Mulloy K, Goldstein J, Tenenbaum N, Wise L. Costs, quality, and the volume of surgical oncology procedures. Arch Surg. 1990; 125:360–363. PMID: 2106311.

11. Kelly JV, Hellinger FJ. Physician and hospital factors associated with mortality of surgical patients. Med Care. 1986; 24:785–800. PMID: 3762245.

12. Hermanek P, Sobin LH. UICC TNM classification of malignant tumors. 1992. 4th edition. Berlin: Springer;2nd revision.

13. Fielding LP. Surgeon-related variability in the outcome of cancer surgery. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1988; 10:130–132. PMID: 3047213.

14. Stocchi L, Nelson H, Sargent DJ, O'Connell MJ, Tepper JE, Krook JE, et al. Impact of surgical and pathologic variables in rectal cancer: a United States community and cooperative group report. J Clin Oncol. 2001; 19:3895–3902. PMID: 11559727.

15. Moriwaki Y, Kobayashi S, Kunisaki C, Harada H, Imai S, Kido Y, et al. Is D2 lymphadenectomy in gastrectomy safe with regard to the skill of the operator? Dig Surg. 2001; 18:111–117. PMID: 11351155.

16. McCulloch P. D1 versus D2 dissection for gastric cancer. Lancet. 1995; 345:1516–1518. PMID: 7769934.

17. Parikh D, Johnson M, Chagla L, Lowe D, McCulloch P. D2 gastrectomy: lessons from a prospective audit of the learning curve. Br J Surg. 1996; 83:1595–1599. PMID: 9014684.

18. Hartgrink HH, Bonenkamp HJ, van de Velde CJ. Influence of surgery on outcomes in gastric cancer. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2000; 9:97–117. PMID: 10601527.

19. Bonenkamp JJ, Songun I, Hermans J, Sasako M, Welvaart K, Plukker JT, et al. Randomised comparison of morbidity after D1 and D2 dissection for gastric cancer in 996 Dutch patients. Lancet. 1995; 345:745–748. PMID: 7891484.

20. Bonenkamp JJ, Hermans J, Sasako M, van de Velde CJ. Extended lymph-node dissection for gastric cancer. Dutch Gastric Cancer Group. N Engl J Med. 1999; 340:908–914. PMID: 10089184.

21. Cuschieri A, Fayers P, Fielding J, Craven J, Bancewicz J, Joypaul V, et al. The Surgical Cooperative Group. Postoperative morbidity and mortality after D1 and D2 resections for gastric cancer: preliminary results of the MRC randomised controlled surgical trial. Lancet. 1996; 347:995–999. PMID: 8606613.

22. Cuschieri A, Weeden S, Fielding J, Bancewicz J, Craven J, Joypaul V, et al. Surgical Co-operative Group. Patient survival after D1 and D2 resections for gastric cancer: long-term results of the MRC randomized surgical trial. Br J Cancer. 1999; 79:1522–1530. PMID: 10188901.

23. Barchielli A, Amorosi A, Balzi D, Crocetti E, Nesi G. Long-term prognosis of gastric cancer in a European country: a population-based study in Florence (Italy). 10-year survival of cases diagnosed in 1985-1987. Eur J Cancer. 2001; 37:1674–1680. PMID: 11527695.

24. Maehara Y, Watanabe A, Kakeji Y, Emi Y, Moriguchi S, Anai H, et al. Prognosis for surgically treated gastric cancer patients is poorer for women than men in all patients under age 50. Br J Cancer. 1992; 65:417–420. PMID: 1558797.

25. Roder JD, Bottcher K, Siewert JR, Busch R, Hermanek P, Meyer HJ. Prognostic factors in gastric carcinoma. Results of the German Gastric Carcinoma Study 1992. Cancer. 1993; 72:2089–2097. PMID: 8374867.

Table 1

Five-year survival rates according to the surgeon's annual caseload and consecutive years of practice

Table 3

Summary of the multivariate analyses for postoperative survival, using a cox proportional hazards model

Table 4

Major postoperative morbidity according to the surgeon's annual caseload and consecutive years of practice

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download