Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study is to compare the antiemetic efficacy and tolerability of intravenous dolasetron mesylate and ondansetron in the prevention of acute and delayed emesis.

Material and Methods

From April 2002 through October 2002, a total of 112 patients receiving cisplatin- based combination chemotherapy were randomized to receive a single i.v. dose of dolasetron 100 mg or ondansetron 8 mg, 30 minutes before the initiation of chemotherapy. In the ondansetron group, two additional doses of ondansetron 8 mg were given at intervals of 2 to 4 hours. To prevent delayed emesis, dolasetron 200 mg p.o. daily or ondansetron 8 mg p.o. bid was administered from the 2nd days to a maximum of 5 days. The primary end point was the proportion of patients that experienced no emetic episodes and required no rescue medication (complete response, CR) during the 24 hours (acute period) and during Day 2 to Day 5±2 days (delayed period), after chemotherapy. The secondary end points included the incidence and severity of emesis.

Results

105 patients were evaluable for efficacy. CR rates during the acute period were 36.0% for a single dose of dolasetron 100 mg, and 43.6% for three doses of ondansetron 8 mg. CR rates during the delayed period were 8.0% and 10.9%, respectively. There was no significant difference in the efficacy between the two groups. Adverse effects were mostly mild to moderate and not related to study medication.

Chemotherapy-induced acute and delayed nausea and vomiting are two of the greatest fears of patients with cancer (1~3). Without prophylactic antiemetics, the majority of cancer patients who undergo moderately or highly emetogenic chemotherapy will experience nausea and vomiting. The distressing symptoms of nausea and vomiting have a considerable impact on all aspects of the patients' quality of life and can potentially lead to a patient's refusal to continue with the most effective anti-tumor therapy (1,4,5). Indeed, the failure to control these side effects can lead to 25~50% of patients delaying or refusing possible lifesaving anti-tumor therapy (6). Therefore, treatments used to control nausea and vomiting form a critical part of the supportive care regimen for cancer patients.

The introduction of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists into clinical oncology in the 1990s led to significant improvements in control rates for acute nausea and vomiting associated with emetogenic chemotherapy, and 5-HT3 receptor antagonists are now considered part of the standard of care. Dolasetron mesylate (Anzemet®), is a pseudopelletierine-derivative (7), highly similar to other agents in this class. Dolasetron mesylate has a median serum half-life of 9 minutes and is reduced rapidly to its major metabolite, hydrodolasetron (MDL 74,156). The reduced metabolite, which appears to be responsible for its antiemetic effect (8~13), has a median half-life of approximately 8 hours and is >50 times more potent as a serotonin antagonist than the parent compound (8,9,11,12). In clinical trials, single intravenous or oral doses of dolasetron were effective in preventing acute chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) (14~17). Intravenous doses of 1.8 mg/kg achieved complete suppression of vomiting in approximately 50% of patients receiving highly emetogenic cisplatin- containing chemotherapy and in approximately 60 to 80% of patients receiving moderately emetogenic chemotherapy (18). In the latter setting, oral doses of 200 mg achieved similar response rates. In comparative studies, intravenous dolasetron 1.8 mg/kg was as effective as intravenous granisetron 3 mg or ondansetron 32 mg after highly emetogenic chemotherapy (6), and oral dolasetron 200 mg was equivalent to multiple oral doses of ondansetron (3 or 4 doses of 8 mg) after moderately emetogenic chemotherapy, with a comparable safety profile.

Several 5-HT3 receptor antagonists are available for the prevention of CINV: ondansetron, dolasetron, granisetron, etc. Although these agents have some pharmacological differences in 5-HT3 receptor binding affinity, selectivity and metabolism, these minor variations have not resulted in clinically meaningful differences in the efficacy amongst them. The objective of this study was to compare the efficacy and tolerability of a single, fixed dose of dolasetron with more than two doses of ondansetron 8 mg in the prevention of acute and delayed CINV following the administration of moderately emetogenic chemotherapy such as cisplatin.

Eligible criteria included histologically or cytologically confirmed malignant diseases, age ≥18 years, either chemotherapy naive or non-naive, no history of nausea or emesis from chemotherapy with other agents, and a Karnofsky performance status ≥50%. Female patients who were not sterile or postmenopausal were required to use a prescribed form of birth control and achieve a negative pregnancy test at a prestudy visit. Patients were to receive cisplatin-based chemotherapy (cisplatin ≥60 mg/m2); however, patients were excluded if they were to receive carboplatin (>1.0 g/m2), cyclophosphamide (>1.0 g/m2), nitrogen mustards (>1.5 g/m2), dacarbazine (>1.5 g/m2), or ifosphamide (>1.5 g/m2) during the 24 hours after the cisplatin infusion. Exclusion criteria included preexisting nausea and/or vomiting from brain metastasis or gastrointestinal obstruction, symptoms of hepatic failure, congestive heart failure, cardiomyopathy, first-degree heart block, preexisting complete bundle branch block, or the use of anti-arrhythmic medication. Other exclusion criteria were the evidence of a seizure disorder requiring anticonvulsants and vomiting or Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) Common Toxicity Criteria grade 2 or 3 nausea in the 24 hours preceding chemotherapy. Non-narcotic analgesics were always allowed to be given to the patients, but narcotic analgesics were allowed to be given in the trial period only if the patient was not nauseated over 1 week of use. The administration of any drug with antiemetic activity was not allowed during 24 hours prior to or during the study. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient before trial enrollment.

This single-centered, phase IV, randomized, and open-labeled study was conducted from the 27th of February 2002 to the 4th of October 2002. On Day 1, eligible patients were randomized to receive a single i.v. dose of dolasetron 100 mg or ondansetron 8 mg infused over 15min, administered 30 min before cisplatin-based chemotherapy to control acute emesis. In the ondansetron group, two additional doses of ondansetron 8 mg after chemotherapy were given at intervals of 2 to 4 hours. To prevent delayed emesis, dolasetron 200 mg p.o. daily or ondansetron 8 mg p.o. bid was administered from the 2nd day to a maximum of 5 days after chemotherapy Adjuvant antiemetics, except serotonin antagonists, were given only to patients with severe emesis All patients gave written informed consent.

The primary end point of the study was the proportion of patients considered to have achieved a complete response (CR; defined as no emetic episode and no use of rescue medication) during the first 24 hours (acute period) and the delayed time period (from Day 2 to Day 5±2 days) after chemotherapy administration. Secondary end points included the following: the number of emetic episodes and severity of nausea during the 24 hours after the initiation of chemotherapy; the number of emetic episodes and severity of nausea during the delayed time period (from Day 2 to Day 5±2 days); and the time to administration and need for rescue medication.

Baseline procedures were documented at a prestudy screening visit within 7 days preceding Day 1. Patients were admitted to hospital during at least the first 24 hours after chemotherapy administration (Day 1) and were assessed by clinic staffs. On Day 2 and Day 5±2 days, if patients were discharged, emetic episodes were to be recorded in diaries by the patients. Patient diaries were organized to record the following: emetic episodes; the use of rescue medication; patient global satisfaction; and the severity of nausea, which was evaluated daily until Day 5±2 days.

Safety was assessed by the following: an adverse event (AE) reporting for a period of 15 days (30 days for serious AEs); vital sign measurements; laboratory tests (hematology, blood chemistry, urinalysis); a physical examination; and electrocardiogram (ECG) recordings performed 24 hours and 1 week after drug administration. A subset of patients had an additional ECG evaluation 15 minutes after study drug administration.

The primary efficacy hypothesis of the study was that at least one dose of dolasetron was non-inferior to the ondansetron dose using a maximum delta of 25% for a CR at 24 hours. The number of patients to be included in the study was estimated based on the assumption of a responder rate of 50% in the dolasetron and ondansetron groups (18) and a difference of no more than 25% in the CR rate.

Cohorts for the analyses included an intent-to-treat (ITT) cohort, a per protocol (PP) cohort, and a safety cohort. The primary analysis was performed on the ITT cohort, which included all randomized patients who received chemotherapy and study medication. The PP cohort included all patients who completed the study at least until Day 1 and who were complaint with the study protocol. The PP analysis was performed for the primary efficacy parameter, demographic data, and baseline characteristics. The safety cohort included all treated patients who had at least one safety assessment after treatment with study drugs.

Patients were evaluated between April 2002 and October 2002. A total of 114 patients were randomized to receive one of two treatments, although two of these patients did not receive treatment. Treatment groups received either dolasetron 100 mg (n=56), or ondansetron 8 mg t.i.d. (n=58), respectively. Of the 112 patients treated, 7 were excluded from the ITT analysis because they had received chemotherapy with unacceptably low emetogenic potential. Therefore, 105 patients were included in the ITT cohort analysis.

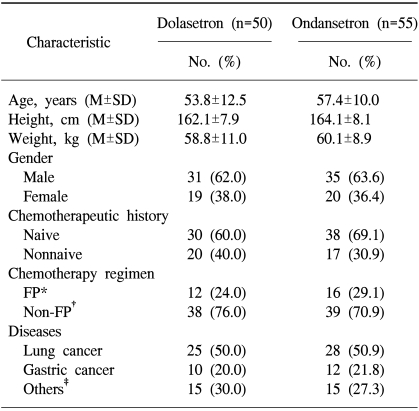

Demographic data and baseline characteristics for patients in the ITT cohort are presented in Table 1. As a result of stratification, the distribution of patients by age, gender, chemotherapeutic history, and types of malignant disease was similar among the two treatment groups. The previous regimen and duration of chemotherapy were not considered in stratification. The most common types of malignant disease included lung cancer (approximately 26%) and gastric cancer (approximately 11%). The majority of patients (65%) were chemotherapy naive. The two treatment groups were comparable regarding the type and dose of chemotherapy administered. No patient received prophylactic corticosteroids. There were no relevant differences between the treatment groups with respect to comorbid medical conditions or the Karnofsky index.

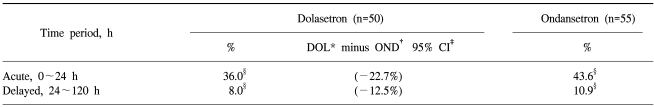

The proportion of patients in the ITT cohort achieving a CR during the first 24 hours after the administration of cisplatin-based chemotherapy is presented in Table 2. The non-inferiority of dolasetron compared with ondansetron was demonstrated, as the lower bound of the 95% CI of the difference with ondansetron (-22.7%) was greater than the preset threshold of the 25% difference.

For the delayed (24~120 hours) time periods, the proportion of patients achieving a CR was similar for ondansetron compared with dolasetron (Table 2). Dolasetron was as effective as ondansetron at all time points.

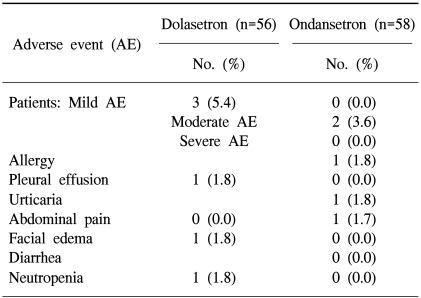

No statistically significant difference was observed for dolasetron compared with ondansetron during the acute and delayed periods (Table 3). Patients treated with dolasetron 100 mg had similar emetic episodes compared with those treated with ondansetron 8 mg t.i.d. during the acute (p=0.3377) and delayed (p=0.1917) periods. More severe nausea and a greater need for rescue medication were observed in the dolasetron treatment group compared with the ondansetron treatment group during the acute and delayed periods, but these differences did not reach statistical significance (Table 3).

A total of 112 patients were evaluable for safety. Dolasetron was well tolerated and no AE-related withdrawals were reported during the study. There were no clinically relevant differences between the treatments with respect to the overall incidence of AEs (Fisher's exact test, p=0.267). Table 4 provides a list of treatment-emergent, drug-related AEs. Six AEs occurred in five patients of the dolasetron group (5/56 patients, 8.9%) and three AEs in two patients of the ondansetron group (2/58 patients, 3.4%). No clinically relevant differences were found between the treatment groups with respect to laboratory test results, vital sign changes, and ECG findings.

Prevention of nausea and vomiting induced by cytotoxic agents is critical in the management of a patient with cancer. The 5-HT3receptor antagonists are currently perceived as the gold standard antiemetic treatment, providing effective control of acute nausea and vomiting, while offering a substantial tolerability benefit over older conventional antiemetics (19).

In this study, a single i.v. dose of dolasetron was as effective as ondansetron in preventing acute and delayed cisplatin-based chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, as indicated by the CR rates and a number of secondary efficacy assessments within the 24 hours following chemotherapy administration. The CR rates observed in this study for dolasetron and ondansetron were inferior to those reported previously (1) (36.0% and 43.6% during the delayed period, 8.0% and 10.9% during the delayed period), especially in delayed emesis control. We could not demonstrate a substantial efficacy of dolasetron in delayed emesis, despite repeated dosing and concomittent use with corticosteroids.

Less is known about the efficacy of 5-HT3 antagonists for the prevention of delayed nausea and vomiting. This can be a serious complication for patients. Kris et al. (20) have reported the incidence to be 93% in patients receiving a high dose of cisplatin. The 5-HT3 antagonists have not been uniformly effective in preventing delayed nausea and vomiting. Urinary excretion of the serotonin metabolite, 5-HIAA, peaks at 6 hours after cisplatin chemotherapy and declines steadily thereafter to pretreatment levels by 24 hours (21,22). This provides evidence that delayed nausea and vomiting are not associated with serotonin release and that other neurotransmitters must be involved.

All treatments were well tolerated with no significant differences between the two groups. Most AEs were assessed as unlikely to be related to study medication, but rather to the patient's underlying cancer or chemotherapeutic agents. A headache, the most frequently reported adverse event in a previous study (23), was rarely of clinical significance and was usually controlled with ease in our study. There were no significant treatment-related changes in laboratory measures, vital signs or ECG.

This study has demonstrated that a single, fixed, i.v. dose of dolasetron 100 mg is effective and safe in preventing cisplatin-based chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Dolasetron was as effective as three doses of ondansetron in preventing acute and delayed chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting.

References

1. Hesketh PJ. Comparative review of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists in the treatment of acute chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Cancer Invest. 2000; 18:163–173. PMID: 10705879.

2. Coates A, Abraham S, Kaye SB, Sowerbutts T, Frewin C, Fox RM, et al. On the receiving end--patient perception of the side-effects of cancer chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1983; 19:203–208. PMID: 6681766.

3. Cooper S, Georgiou V. The impact of cytotoxic chemotherapy--perspectives from patients, specialists and nurses. Eur J Cancer. 1992; 28A(Suppl 1):S36–S38. PMID: 1627406.

4. Doherty KM. Closing the gap in prophylactic antiemetic therapy: patient factors in calculating the emetogenic potential of chemotherapy. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 1999; 3:113–119. PMID: 10690042.

5. A double-blind randomized study comparing intramuscular (i.m.) granisetron with i.m. granisetron plus dexamethasone in the prevention of delayed emesis induced by cisplatin. The Italian Multicenter Study Group. Anticancer Drugs. 1999; 10:465–470. PMID: 10477166.

6. Ritter HL Jr, Gralla RJ, Hall SW, Wada JK, Friedman C, Hand L, et al. Efficacy of intravenous granisetron to control nausea and vomiting during multiple cycles of cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Cancer Invest. 1998; 16:87–93. PMID: 9512674.

7. Gittos M, Fatmi M. Potent 5-HT3 antagonists incorporating a novel bridged pseudopelletierine ring system. Actual Chim Ther. 1989; 16:187–189.

8. Boxenbaum H, Gillespie T, Heck K, Hahne W. Human dolasetron pharmacokinetics: I. Disposition following single- dose intravenous administration to normal male subjects. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 1992; 13:693–701. PMID: 1467456.

9. Boeijinga PH, Galvan M, Baron BM, Dudley MW, Siegel BW, Slone AL. Characterization of the novel 5-HT3 antagonists MDL 73147EF (dolasetron mesilate) and MDL 74156 in NG108-15 neuroblastoma x glioma cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992; 219:9–13. PMID: 1397053.

10. Galvan M, Gittos M, Miller R. Dolasetron mesilate (MDL 73147EF), a potent anti-emetic 4-HT3 receptor antagonist. Br J Pharmacol. 1992; 107(suppl):449.

11. Miller R, Galvan M, Gittos M. Pharmacological properties of dolasetron, a potent and selective antagonist at 5-HT3 receptors. Drug Dev Res. 1993; 28:87–93.

12. Shah A, Lanman R, Bhargava V, Weir S, Hahne W. Pharmacokinetics of dolasetron following single- and multiple-dose intravenous administration to normal male subjects. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 1995; 16:177–189. PMID: 7787130.

14. Conroy T, Cappelaere P, Fabbro M, Fauser AA, Splinter TA, Spielmann M, et al. Acute antiemetic efficacy and safety of dolasetron mesylate, a 5-HT3 antagonist, in cancer patients treated with cisplatin. European Dolasetron Study Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1994; 17:97–102. PMID: 8141114.

15. Kris mg, Grunberg SM, Gralla RJ, Baltzer L, Zaretsky SA, Lifsey D, et al. Dose-ranging evaluation of the serotonin antagonist dolasetron mesylate in patients receiving high-dose cisplatin. J Clin Oncol. 1994; 12:1045–1049. PMID: 8164028.

16. Plezia P, Modiano M, Alberts D. A double-blind, randomized, parallel study of two doses of intravenous MDL73, 147EF in patients (PTS) receiving high cisplatin (CDDP)-containing chemotherapy (CT). Proc Soc Clin Oncol. 1992.

17. Hesketh PJ, Gandara DR, Hesketh AM, Facada A, Perez EA, Webber LM, et al. Dose-ranging evaluation of the antiemetic efficacy of intravenous dolasetron in patients receiving chemotherapy with doxorubicin or cyclophosphamide. Support Care Cancer. 1996; 4:141–146. PMID: 8673351.

18. Hesketh P, Navari R, Grote T, Gralla R, Hainsworth J, Kris M, et al. Double-blind, randomized comparison of the antiemetic efficacy of intravenous dolasetron mesylate and intravenous ondansetron in the prevention of acute cisplatin-induced emesis in patients with cancer. Dolasetron Comparative Chemotherapy-induced Emesis Prevention Group. J Clin Oncol. 1996; 14:2242–2249. PMID: 8708713.

19. Im YH, Park YS, Jang JS, Lee JY, Yoon SS, Heo DS, et al. A randomized comparison of antiemetic effect of ondansetron versus MDL (Metoclopramide/Dexamethasone/Lorazepam) in patients receiving cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy. J Korean Cancer Assoc. 1992; 24:378–389.

20. Kris MG, Gralla RJ, Tyson LB, Clark RA, Cirrincione C, Groshen S. Controlling delayed vomiting: double-blind, randomized trial comparing placebo, dexamethasone alone, and metoclopramide plus dexamethasone in patients receiving cisplatin. J Clin Oncol. 1989; 7:108–114. PMID: 2642536.

21. Wilder-Smith OH, Borgeat A, Chappuis P, Fathi M, Forni M. Urinary serotonin metabolite excretion during cisplatin chemotherapy. Cancer. 1993; 72:2239–2241. PMID: 7690681.

22. Elizabeth G, David S. 5-HT3 receptor antagonists for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Drugs. 1998; 55:173–189. PMID: 9506240.

23. Barisano A, Mehl B, Bradbury K. Serotonin antagonists: treatment of chemotherapy-induced emesis. Mt Sinai J Med. 1992; 59:433–437. PMID: 1435844.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download