Abstract

The association between a multiple myeloma and a secondary solid tumor is not well established. Some reports showed an increased risk of secondary solid neoplasms in multiple myeloma patients, but others have not. Three cases of the synchronous occurrence of multiple myelomas and solid tumors, namely, a small cell carcinoma of the lung, an adenocarcinoma of the colon and a squamous carcinoma of the pyriform sinus were experienced at our hospital. Therefore, herein is reported the clinical courses and treatment results. The stage of multiple myeloma was Durie-Salmon stage I in all of three cases; therefore, the solid tumors were treated as a primary target because the prognosis of early stage multiple myeloma is generally better than that of advanced solid tumor, while a smoldering or stage I myeloma do not need primary therapy until progression of the multiple myeloma. Two patients died of their solid tumors, but one patient is alive.

A multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignant disease of plasma cells, which manifests as one or more of lytic bone lesions, monoclonal protein in the blood and/or urine and disease in the bone marrow (1). The diagnosis of a secondary solid neoplasm in patients with a MM is uncommon, and it is debatable whether the MM itself is a risk factor for the incidence of a secondary solid neoplasm (2~5). Although the development of a second primary cancer generally results from carcinogenic agents, such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy (6), the pathogenesis of second primary cancer in a MM, or vice versa has not definitely been associated with alkylating therapy (3). It has been suggested that myeloma patients may have an immunologic tolerance for developing solid tumors, since these patients have an impaired immune system. A second solid tumor in patients with a MM has rarely been reported in Korea, with all reported solid tumors being stomach cancers (7~9). In our hospital, three cases of the synchronous occurrence of a MM and solid tumors, namely, small cell carcinoma of the lung, adenocarcinoma of the colon and squamous carcinoma of the pyriform sinus were experienced. Thus, herein these 3 cases, which simultaneously presented with a MM, are reported and their clinical courses and treatment results described.

A 51-year-old man presented in July 2002 with a productive cough of 1 month duration. A chest x-ray and chest CT revealed multiple conglomerated lymph nodes in the right hilar, mediastinal and right supraclavicular lymph node regions, with post-obstructive pneumonitis in the superior segment of the right lower lobe (RLL). A bronchoscopic biopsy at the mucosal nodularity in the superior segment of the RLL was performed, with the histologic review of the biopsy specimen revealing a small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC). A bone marrow (BM) aspirate and biopsy, for routine staging procedureof the SCLC, incidentally showed dysplastic plasma cells that accounted for up to 52% of the absolute neutrophil count (ANC), without evidence of small cell carcinoma involvement. Laboratory tests revealed the presence of mild anemia (hemoglobin, 12.3 g/dL), an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 70 mm/hr (normal value, <22 mm/hr), total serum protein of 6.6 g/dL, serum creatinine of 1.0 mg/dL, serum calcium of 9.3 mg/dL, C-reactive protein (CRP) of 3.6 mg/dL and serum beta-2 microglobulin of 3.1 mg/L. Serum electrophoresis (EP) and immunoelectrophoresis (IEP) showed abnormally bowed arcs against IgG and anti-lambda light chain. No lytic bony lesion was demonstrated on a skeletal survey. The SCLC was diagnosed as a limited disease and the MM as an IgG - lambda type (Durie-Salmon stage I). The patient received concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy for the SCLC (five cycles of etoposide/carboplantin and 4,400 cGy/22 Fx). The follow up evaluation showed a progressive disease and brain metastasis. The patient received palliative whole brain radiotherapy and second line chemotherapy, but expired due to progression of brain metastasis.

A 64 year-old male patient was referred to our division in May 2002 for the management of metastatic colon cancer. He had previously undergone a right hemicolectomy in January 2001, and then received doxifluridine as an adjuvant treatment until July 2001. A CT scan on April 2001 showed multiple hepatic and pulmonary metastases. During three courses of combination chemotherapy, with oxaliplantin, 5-FU and leucovorin, his blood examination showed an elevated serum protein level of 9.3 mg/dL and a reversed albumin/globulin (A/G) ratio of 0.8. The serum EP and IEP showed abnormally bowed arcs against IgG and anti-lambda light chain. Other blood tests showed hemoglobin of 13.0 g/dL, serum calcium of 8.6 mg/dL, serum creatinine of 1.2 mg/dL, beta-2 microglobulin of 1.72 mg/L, and serum IgG/A/M of 3430, 24.1 and 45.5 mg/dL, respectively. The BM aspirate and biopsy showed dysplastic plasma cells that accounted for up to 31% of the ANC. A skeletal survey of the plain X-ray films revealed no lytic bony lesions. A diagnosis of a MM (Durie-Salmon stage I) was made. The patient received three more cycles of oxaliplatin, leucovorin and 5-FU, but showed a progressive disease, refractory to chemotherapy, and later died of colon cancer.

A 60 year-old man was admitted to our hospital for the evaluation of odynophagia. An esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed a friable multi-lobulated and ulcerated mass on the right pyriform sinus, and a biopsy demonstrated a moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. Neck CT showed lymph node enlargement in levels II and III. The patient was diagnosed with pyriform sinus cancer, at stage IVA according to the criteria of the AJCC . Laboratory examinations showed an elevated serum protein level of 9.0 mg/dL and a reversed A/G ratio of 0.5, hemoglobin of 11.3 g/dL, serum calcium of 8.0 mg/dL, serum creatinine of 1.1 mg/dL, beta-2 microglobulin of 3.29 mg/L, and serum IgG/A/M of 6450, 21.1 and 41.5 mg/dL, respectively. The serum EP and IEP demonstrated an M-component of IgG (3.8 g/dL) and a spike of IgG and anti-kappa chains. A BM aspirate and biopsy showed abnormal plasma cells, which accounting for up to 34.1% of the ANC, with dysplastic features, and was thus diagnosed with MM (Durie-Salmon stage I). A skeletal survey of the plain X-ray films revealed no lytic bony lesion. The patient received concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy for his pyriform sinus cancer (five cycles of cisplatin and 7,020 cGy/39 Fx). A follow up neck CT showed complete remission; the patient is being regularly followed up, and is currently in a state of complete remission.

With increases in routine health screening, MM is now diagnosed earlier, and those patients with typical symptoms related to a MM reduced (10). Our cases of a MM with solid tumors had no initial typical symptoms of a MM, such as bone pain, fatigue, weight loss or infection. All were incidentally diagnosed with a MM during the initial work-up or follow-up evaluation of known solid tumors. All three patients had Salmon-Durie stage I, with beta-2 microglobulin levels below 4 mg/L. Patients with a smoldering or stage I MM require no primary therapy as they can do well for many months or years before the disease progresses (4). These patients should initially be observed until progression of the MM, which is defined as a sustained 25% or greater increase in the M-protein in the serum or urine, and the development of new sites of a lytic disease or hypercalcemia. Because the prognosis of advanced solid tumors is generally poorer than that of an early stage MM, it was decided to treat the solid tumors as a primary disease. Although the response to chemotherapy seemed to be similar to that in patients without a MM, all three patients frequently showed grade 3~4 neutropenia and/or thrombocytopenia during the course of chemotherapy, despite having normal blood cell counts before the first chemotherapy. An initial BM exam showed normocellular (two patients) or hypercellular (one patient) bone marrow for their ages, but their cellularities might have been overestimated due to the packed dysplastic plasma cells in the BM. Therefore, the doses of chemotherapeutic agents were reduced and the cycle intervals frequently delayed, which might have resulted in the suboptimal response of the chemotherapy. Therefore, these patients should be monitored frequently during chemotherapy, with the use of CSF (Colony-stimulating factor) considered to maintain the dose intensity. None of the three patients experienced serious infection or hemorrhagic episodes during the chemotherapy.

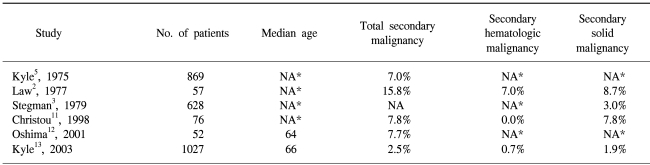

In general, it is unclear whether a MM itself is a risk factor for the incidence of secondary solid neoplasms (2~5). The use of alkylating agents and an immunologic tolerance have been suggested as a possible mechanism accounting for the development of a second primary tumor in patients with a MM or vice versa; however, this has not been conclusively proved (3). Six large MM group studies have been reviewed for this study, which are summarized in Table 1 (2,3,5,11~13).

According to the most recent national surveys of cancer patients in the United States (14) and Korea (15), the cumulative probability of developing any type of malignancy, with the exception of in-situ neoplasms, in patients aged 60 years has been shown to be approximately 1.5% per year. Since the median survival of patients with a MM is 33 months (13), the age-specific risk of developing any cancer for MM patients can be speculated to be approximately 4.5% during their survival duration. Six studies have shown that a MM was associated with an increased risk of secondary malignancies, including hematologic malignancies and solid cancers. However, a MM was not clearly correlated with an increased risk for developing a secondary solid malignancy. Two small series have shown an increased risk for secondary solid cancer, whereas two larger series failed to demonstrate any correlation. Therefore, it is suggested that a MM may be associated with an increased risk of secondary malignancies, including hematologic and non-hematologic malignancies, although the correlation between a MM and secondary solid cancer is unclear.

References

2. Law IP, Blom J. Second malignancies in patients with multiple myeloma. Oncology. 1977; 34:20–24. PMID: 405642.

3. Stegman R, Alexanian R. Solid tumors in multiple myeloma. Ann Intern Med. 1979; 90:780–782. PMID: 434680.

5. Kyle RA. Multiple myeloma: review of 869 cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1975; 50:29–40. PMID: 1110582.

6. Kyle RA, Pierre RV, Bayrd ED. Multiple myeloma and acute myelomonocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1970; 283:1121–1125. PMID: 5273282.

7. Park CS, Suh SP, Choi SI, Yoo JY. Multiple myeloma associate with adenocarcinoma of the Stomach. Korean J Pathol. 1982; 16:532–535.

8. An HJ, Han KJ, Kim WI, Shim SI. Multiple myeloma associate with adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Korean J Pathol. 1986; 20:191–194.

9. Jeong SM, Cho CH, Yoon JH, Hur M, Yoon JW, Hahn JS, Ko YW. A Case of multiple myeloma associated with stomach cancer. Korean J Hematol. 1984; 19:343–348.

10. Riccardi A, Gobbi PG, Ucci G, Bertoloni D, Luoni R, Rutigliano L, Ascari E. Changing clinical presentation of multiple myeloma. Eur J Cancer. 1991; 27:1401–1405. PMID: 1835856.

11. Christou L, Tsiara S, Frangides Y, Pnevmatikos J, Briasoulis E, Galanakis E, Bourantas KL. Patients with multiple myeloma and solid tumors: six case reports. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 1998; 17:239–242. PMID: 9700587.

12. Oshima K, Kanda Y, Nannya Y, Kaneko M, Hamaki T, Suguro M, Yamamoto R, Chizuka A, Matsuyama T, Takezako N, Miwa A, Togawa A, Niino H, Nasu M, Saito K, Morita T. Clinical and pathologic findings in 52 consecutively autopsied cases with multiple myeloma. Am J Hematol. 2001; 67:1–5. PMID: 11279649.

13. Kyle RA, Gertz MA, Witzig TE, Lust JA, Lacy MQ, Dispenzieri A, Fonseca R, Rajkumar SV, Offord JR, Larson DR, Plevak ME, Therneau TM, Greipp PR. Review of 1,027 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003; 78:21–33. PMID: 12528874.

14. Jemal A, Tiwari RC, Murray T, Ghafoor A, Samuels A, Ward E, Feuer EJ, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2004. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004; Jan–Feb. 54:8–29. PMID: 14974761.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download