Abstract

Laryngeal cancers account for approximately 1.5% (1~2%) of the total cancers in Korea, and 30% of all head and neck cancers, not including thyroid cancer. Early laryngeal cancer is treated by operation, including transoral laser excision or radiotherapy. Advanced laryngeal cancer has been treated with mutilating operations, such as a total laryngectomy. However, a laryngeal preserving approach, which can improve the quality of life, has recently been tried with advanced laryngeal cancer.

Laryngeal cancer is known to be associated with tobacco use, alcohol abuse and other chemical carcinogens. The incidence of laryngeal cancer in smokers is 4~24 times that of non-smokers. Alcohol abuse induces supraglottic rather than glottic cancer. Laryngeal cancer consists of almost entirely of squamous cell carcinomas (over 95%); others are verrucous carcinomas, adenocarcinomas, sarcomas and minor salivary gland malignancies, etc.

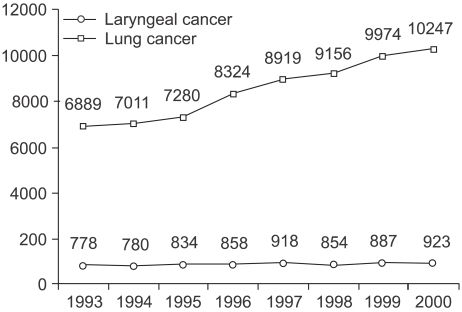

The incidence of laryngeal cancer has been associated with lung cancer. In Korea, until 1997, the incidence of laryngeal cancer increased every year, proportionally to that of lung cancer. But, since 1998 the incidence of laryngeal cancer has plateaued, nevertheless, lung cancer is steadily increasing (Fig. 1).

The larynx has three subsites: the supraglottis, the glottis and the subglottis. In the USA, glottic cancer accounts for 60% of all laryngeal cancers, 35% of supraglottic cancers and 5% of subglottic cancers, and in Korea in 1991, supraglottic and glottic cancers account for 49.5 and 37% of laryngeal cancers. Tumors that arise from each of the subsites must be treated according to their characteristic. Because glottic cancer is seldom metastatic to the neck, neck treatment at an early stage is not considered. Conversely, supraglottic cancer is metastatic to the neck at early stage, so neck management is always considered. Subglottic cancer is very rare, but theoretically can metastasize to the neck at early stage.

The first treatment of laryngeal cancer was a tracheostomy, which was performed by Trousseau in 1837. In 1863, Sands obtained the first long-term control of cancer via a laryngofissure. The use of a laryngofissure has continued over the years for the control of smaller and intrinsic lesions of the larynx, but was not thought to be applicable to extrinsic tumors. After Billroth's first successful total laryngectomy in 1873 (1), more attention has paid to the use of total extirpative surgery, which has continued to the inclusion of a total laryngectomy, with en bloc radical neck dissection (2).

Billroth performed the first vertical hemilaryngectomy, in 1878, five years after his first total laryngectomy. Supraglottic & supracricoid laryngectomies, with a cricohyoidopexy, were first performed in 1940s. In 1973, Jako and Strong studied, and developed, laser laryngeal surgery.

In 1885, Roentgen discovered X-rays, and in 1903 Schepegrell first used X-rays to treat laryngeal cancer. At the beginning of the twentieth century, cancer of the larynx was one of the first tumors treated, and cured, with the use of radiotherapy. Radiotherapy has been use in the treatment of early, small malignancies, and in attempts to palliate large tumors that were beyond the scope of surgical removal.

The T stage of laryngeal cancer is important, with early laryngeal cancer includes T stages 1 and 2, and patients with early laryngeal cancer have a greater opportunity for preservation of the larynx than those with advanced laryngeal cancer, or those at T stages 3 and 4. Patients with early stage laryngeal cancer are usually treated with multiple surgical methods (transoral laser cordectomy, laryngofissure cordectomy, vertical partial laryngectomy or supraglottic subtotal laryngectomy) or radiotherapy alone.

Many patients with advanced stage laryngeal cancer used to be treated with a total laryngectomy, but recently, the combination therapy of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, following an operation or radiotherapy, has been tried. The use of platinum salts at the end of the 1970s, and the combination of cisplatin and 5-FU at the beginning of the 1980s, have changed the situation by leading to the complete macroscopic disappearance of tumors in 30~40% of previously untreated patients. It very soon became apparent that most chemosensitive tumors were also radiosensitive. This provided the basis for the development of a new strategy, leading to the preservation of the larynx in selected patients: after the initial chemotherapy, the good responders received radiotherapy, and the poor responders underwent a total laryngectomy.

A therapeutic neck dissection is performed at the time of initial surgery in patients with clinical node involvement. An elective neck dissection is generally carried out in patients with cancer of the supraglottic larynx.

Postoperative radiotherapy is given to the primary site and neck, based on the clinicopathological risk factors: positive or closed surgical margins, perineural invasion, multiple lymph node involvement in the neck or extracapsular spread.

Two treatment options are widely used for the cure of T1 glottic squamous cell carcinomas: radiotherapy and surgical removal. There is ongoing controversy about whether laser excision should be offered to patients with T1 glottic carcinomas. Carcinomas of the glottis are usually diagnosed in the early stage of the disease, with malignant spread to regional lymph nodes seldom seen, and distant metastases extremely rare (3). These pathological characteristics, and the fact that effective treatment is available, are the basis of the relatively good prognosis of this type of malignancy.

Transoral laser excision allows the surgeon to offer an effective, definitive treatment for glottic cancers, and is less expensive and more convenient than traditional external beam radiotherapy (3,4).

Two studies were found to be comparative, i.e. as they included control groups receiving radiotherapy (5,6). In a retrospective study, by Epstein et al., the outcomes of 60 patients who received radiotherapy (43 T1a and 17 T1b) or an endoscopic laser resection (17 patients with T1a) were compared (6). They found the local control rate was significantly higher in the radiotherapy than in the laser treatment group, with 3-year local control rates of 89 and 77%, respectively (p=0.042). However, the patients were not randomized, and the selection of the treatment option was based on the referral patterns and patient preferences. In an extensive comparison between radiotherapy, partial laryngectomy and laser resection, by Rosier et al., no significant difference was detected in the locoregional control at 5 years. A relatively large proportion of the laser-treated patients required postoperative radiotherapy, due to residual carcinomas at resection borders (30%).

Laser treatment affords an additional line of treatment, as recurrences can be treated with radiotherapy, thus sparing patients from a salvage laryngectomy. However, one of the drawbacks of laser treatment, as a primary intervention, might be that complete removal of the tumor is not possible in every case, and additional therapy may be needed. This increases the treatment load on the patient, as well as increasing the costs. Laser treatment should only be considered in small, mid-cord tumors at one vocal cord, without impaired mobility (T1a) (7).

There is some controversy about the applicability of laser treatment for malignant tumors localized at the anterior commissure. Most authors state that it is contraindicated to apply laser excision in this region, while others advocate that, if the right surgical technique is used, laser is the treatment of choice (8). However, the poorer outcome of these patients, regardless of the treatment option used, might be due to unrecognized microinvasion of the thyroid cartilage. In a study by Krespi et al (9), all patients with carcinomas localized at the anterior commissure, treated with laser, had a tumor recurrence, and in most cases additional treatment was necessary, i.e. laryngectomy or radiotherapy. These findings were in contrast to the experience of Motta et al (8). They report good tumor control at the anterior commissure, but no actual survival data on this subgroup of patients was given. An extensive investigation by Wolfensberger et al (10), clearly indicated that involvement of the anterior commissure reduced the respectability of the tumor. However, patients with a tumor localized at the anterior commissure, receiving radiotherapy, also face an increased risk of a recurrence. At present, it is generally accepted that tumors localized to the anterior commissure are contraindicatory to laser resection, and radiotherapy is the treatment of choice with this type of malignancy.

The effectiveness of a transoral laser excision directly depends on the physician's ability to identify and visualized the limits of the tumor. When the tumor is obscured by a submucosal location or edematous tissue, transoral laser excision becomes more difficult; and therefore, less reliable (11). Recommended indications for radiotherapy are: 1) recurrence after one or more prior vocal fold strippings, 2) recurrence in a short period after stripping, 3) an inability to follow closely after treatment, 4) the voice quality is critical (professional singers), 5) overall poor operative risks, and 6) anterior commissure lesion of inaccessible for complete endoscopic ablation.

The larynx is unique, in that it is a very small organ, but has been subjected to intensive clinical research. Indeed, there are at least 15 surgical procedures for laryngeal cancers, which in addition to a total laryngectomy, allow surgeons to deal with any kind of local extension.

The indications and problems of an organ-preserving vertical partial laryngectomy (VPL), in T1b glottic or T2 glottic and subglottic cancers, are well known. The first, and imperative, requirement for the surgeon is the adequate resection of the tumor, while the second prerequisite is the safe and successful correction of the excised portion of the anterolateral wall of the larynx. Krajina's method (12), for the reconstruction of the larynx, utilizes the pedicled sternohyoid fascia, which is thin, elastic, well adaptable to defects and resistant to infection or saliva. By providing a large surface for covering the defects, granulations and synechiae can be prevented.

The conventional treatment of choice for supraglottic cancer, not involving a vocal cord, is a horizontal supraglottic laryngectomy.

There are two major conventional therapeutic options: radical surgery (such as total laryngectomy), with optional postoperative or definitive radiotherapy, with surgery kept in reserve for salvage in the case of a respectable local recurrence. One of the most recent clinical report of a total laryngectomy presented local control and 5-year survival rates of 86 and 67%, respectively (13). Despite this high success rate, a total laryngectomy has a low patient compliance, as it is a mutilating procedure.

A supracricoid partial laryngectomy (SCPL) is a suitable conservative procedure, which can be used as an alternative to a mutilating procedure for advanced supraglottic and glottic cancers. SCPL, with a cricohyoidopexy, is indicated by supraglottic cancer, with involvement of the ventricle, vocal cord limited preepiglottic space and paraglottic space, and by glottic cancer, with involvement of the anterior commissure, paraglottic space and ventricle, or with limited thyroid cartilage invasion. A retrospective study, with 146 patients who have supraglottic cancer, presented a laryngeal preservation, 3 and 5 year survival rates of 85, 92 and 88%, respectively (14). SCPL is especially useful for recurrent laryngeal cancer following radiotherapy. A study, with 12 patients after failed laryngeal radiotherapy, reported 3 year survival local control and laryngeal preservation rates of 83.3 and 75%, respectively (15).

After World War II, chemotherapy became a new tool against cancer. Up to the end of the 1970s, however, no regimens was sufficiently active against head and neck squamous cell carcinomas, so chemotherapy was mainly used for palliation (advanced unresectable, recurrent, or metastatic disease). The appearance of platinum-based chemotherapy, particularly the combination of cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), completely modified the rationale, with the possibility of integrating chemotherapy into protocols with curative intent. Impressive response rates, as high as 80%, for objective responses, and 40 to 50% for complete responses, have been observed in previously untreated patients. It quickly became apparent that chemosensitive tumors were also radiosensitive in most cases. This apparent ability, of neoadjuvant chemotherapy to predict radiosensitivity, led some teams to assess the possibility of avoiding total ablation of the larynx, using upfront chemotherapy, followed in the good responders by radiotherapy, and in the poor responders by the initially planned surgery. Unfortunately, most attempts to preserve the larynx were carried out in non-controlled trials, which used historical comparisons with other surgical series.

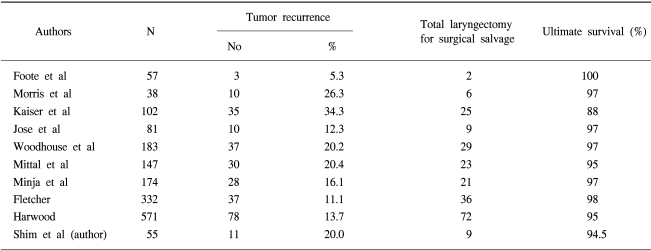

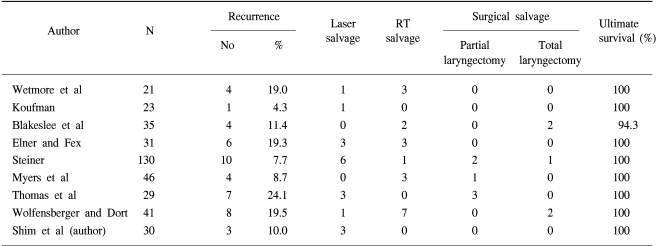

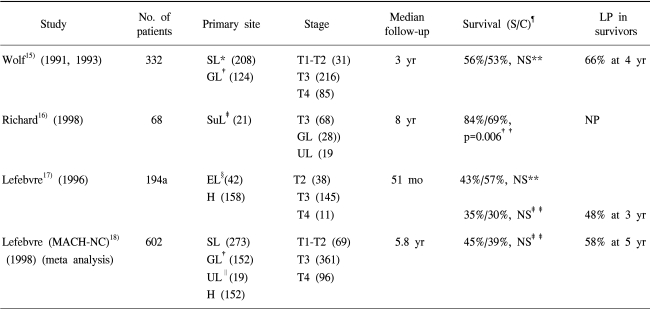

Many series have assessed the reliability of neoadjuvant chemotherapy-based protocols in a nonrandomized fashion. Roughly speaking, these series have presented that laryngeal preservation can be achieved in one-third to one-half of patients. Only four randomized trials (16~19) have been reported (Table 3). There was no significant difference in survival between the mutilating surgery and neoadjuvant chemotherapy groups, with the exception of the report by Richard (17). However, in this report a laryngeal preservation rate of over 50% was achieved in the survivors.

Ultimate local control in radiotherapy (including salvage surgery, in most cases a total laryngectomy) was similar to that in the surgical series of laryngeal cancers. An important retrospective study, from Christie Hospital, recently appeared (20). A total of 114 patients, with T3N0 glottic carcinomas, were treated by radiotherapy, between 1986 and 1994. The 5-year overall survival was 54%, with a 5-year local control, after radiotherapy alone, and after salvage surgery, of 68 and 80%, respectively. These results indicate the magnitude of the problem: In such cases surgery is able to ensure local control in almost all cases, but the price paid is the loss of voice. In contrast, radiotherapy (including salvage surgery) achieved only 80% local control, but two-thirds of the larynxes were preserved.

There are two other radiotherapy-based protocols. One is the modified fractionation schemes. The role of accelerated or hyperfractionated treatment is to increase the total dose delivered and, if possible, shorten the overall treatment time. A study shows that a reduction in the treatment time resulted in a significant benefit in tumor control and a similar but not significant benefit was found regarding survival (21) The other is concomitant chemoradiotherapy. Concomitant chemoradiotherapy could be a highly effective way of increasing the locoregional control of advanced head and neck tumors. Some advanced laryngeal tumors have been entered into randomized studies, which are examining the role of chemotherapy combined with radiotherapy. Merlano et al. included 26% of tumors in a combined-therapy arm (four courses of chemotherapy alternating with three courses of radiotherapy) and 31% in a radiotherapy-alone arm. The complete tumor response and 3-year survival rates were significantly in favor of the combined-therapy). This protocol is currently being compared for sequential organ preservation combined treatment in an EORTC Phase III study (EORTC 24954).

Finally, hyperfractionated radiotherapy (75 Gy twice daily in 1.25 Gy doses) was compared with combined chemoradiotherapy (four courses of CDDP/5-FU for 5 days with the same fractionation scheme). Of the 116 randomized patients, 36% presented with laryngeal and hypopharyngeal tumors, mostly at stages T3 and 4 (88%). The overall and relapse-free survivals, and the locoregional control were significantly in favor of the combined-therapy regimen (23).

These preliminary results suggest, there was no difference in the overall survival, fewer distant metastases when chemotherapy was delivered and a trend for higher larynx preservation rates, with the concurrent chemoradiotherapy. The long-term results are still to be assessed.

Too many parameters remain to be evaluated to assess the efficacy of the various modalities used to eradicate primary laryngeal tumors, and preserve the laryngeal form and function. Many factors, in addition to local extension, may influence decision-making. Little is known about the proportion of patients that can actually benefit from preservation protocols. Finally, parameters, such as the quality of life, cost-effectiveness and the reproducibility of various strategies, from one institution to another, have been underevaluated.

The lessons learnt from this intensive clinical research are difficult to incorporate into daily practice, and the most appropriate way to select patients to undergo the various strategies is still a concern. Some parameters are linked to the treating physician, others to the patient and probably many to the tumor itself, particularly the biological characteristics. At present, the preservation of the laryngeal form and function remains a challenge that must be permanently assessed by multidisciplinary clinical research.

References

1. Absolon KB. Theodore Billroth in Vienna 1867~1880. Aust N Z J Surg. 1977; 47:837–844. PMID: 348184.

2. Brunschwig A. Panlaryngectomy for advanced carcinoma of the larynx. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1943; 76:390–394.

3. Cragle SP, Brandenburg JH. Laser cordectomy or radiotherapy: Cure rates, communication, and cost. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993; 108:648–654. PMID: 8516002.

4. Foote RL, Buskirk SJ, Grado GL, Bonner JA. Has radiotherapy become too expensive to be considered a treatment option for early glottic cancer? Head Neck. 1997; 19:692–700. PMID: 9406748.

5. Rosier JF, Gregoire V, Counoy H, Octave-Prignot M, Rombaut P, Scaliet P, Vanderlinden F, Hamoir M. Comparison of external radiotherapy, laser microsurgery and partial laryngectomy for the treatment of T1N0M0 glottic carcinomas: a retrospective evaluation. Radiother Oncol. 1998; 48:175–183. PMID: 9783889.

6. Epstein BE, Lee DJ, Kashima H, Johns ME. Stage T1 glottic carcinoma: results of radiation therapy or laser excision. Radiology. 1990; 175:567–570. PMID: 2326483.

7. Luscher MS, Pedersen U, Johansen LV. Treatment outcome after laser excision of early glottic squamous cell carcinoma (A literature survey). Acta Oncol. 2001; 40:796–800. PMID: 11859977.

8. Motta G, Esposito E, Cassiano B, Motta S. T1-T2-T3 glottic tumors: fifteen years' experience with CO2 laser. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1997; (Suppl 527):155–159. PMID: 9197509.

9. Krespi YP, Meltzer CJ. Laser surgery for vocal cord carcinoma involving the anterior commissure. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1989; 98:105–109. PMID: 2916820.

10. Wolfensberger M, Dort JC. Endoscopic laser surgery for early glottic carcinoma: a clinical and experimental study. Laryngoscope. 1990; 100:1100–1105. PMID: 2215043.

11. Beitler JJ, Johnson JT. Transoral laser excision for early glottic cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003; 56:1063–1066. PMID: 12829142.

12. Krajina ZF, Kosokovic S, Vecerina S. Laryngeal reconstruction with sternohyoid fascia in partial laryngectomy. J Laryngol Otol. 1979; 93:1181–1186. PMID: 528818.

13. Hall FT, O'Brien CJ, Clifford AR, McNeil EB, Bron L, Jackson MA. Clinical outcome following total laryngectomy for cancer. ANZ J Surg. 2003; 73:300–305. PMID: 12752286.

14. Schwaab G, Kolb F, Julieron M, Janot F, Le Ridant AM, Mamelle G, Marandas P, Koka VN, Luboinski B. Subtotal laryngectomy with cricohyoidopexy as first treatment procedure for supraglottic carcinoma: Institut Gustave-Roussy experince (146 cases, 1974-1997). Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2001; 258:246–249. PMID: 11548904.

15. Laccourreye O, Weinstein G, Naudo P, Cauchois R, Laccourreye H, Brasnu D. Supracricoid partial laryngectomy after failed laryngeal radiation therapy. Laryngoscope. 1996; 106:495–498. PMID: 8614228.

16. Wolf GT, Hong WK. Induction chemotherapy as part of a new treatment strategy to preserve the larynx in advanced laryngeal cancer. Head and Neck Cancer. 1993; 3:27–35.

17. Richard JM, Sancho-Garnier H, Pessey JJ, Luboinski B, Lefebvre JL, Dehesdin D, Stranboni-Luboinski M, Hill C. Randomized trial of induction chemotherapy in larynx carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 1998; 34:224. PMID: 9692058.

18. Lefebvre JL, Chevalier D, Luboinski B, Kirkpatrick A, Collette L, Sahmoud T. Larynx preservation in pyriform sinus cancer: preliminary results of a European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer phase III study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996; 13:890. PMID: 8656441.

19. Lefebvre JL, Wolf G, Luboinski B, Pessey JJ. Meta-analysis of preservation using neoadjuvant chemotherapy (CT) in laryngeal and hypopharyngeal carcinoma. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1998; 17:1473.

20. Wylie JP, Sen M, Swindell R, Sykes AJ, Farrington WT, Slevin NJ. Definitive radiotherapy for 114 cases of T3N0 glottic carcinoma: influence of dose- volume parameters on outcome. Radiother Oncol. 1999; 53:15. PMID: 10624848.

21. Overgaard J, Hansen HS, Overgaard M, Bastholt L, Berthelsen A, Specht L, Lindelov B, Jorgensen K. A randomized double-blind phase III study of nimorazole as a hypoxic radiosensitizer of primary radiotherapy in supraglottic larynx and pharynx carcinoma. Results of the Danish Head and Neck Cancer Study (DAHANCA) Protocol 5-85. Radiother Oncol. 1998; 46:135–146. PMID: 9510041.

22. Merlano M, Vitale V, Rosso R, Benasso M, Corvo R, Cavallari M, Sanguineti G, Bacigalupo A, Badellino F, Margarino G. Treatment of advanced squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck with alternating chemotherapy and radiotherapy. N Engl J Med. 1992; 327:1115. PMID: 1302472.

23. Brizel DM, Albers ME, Fisher SR, Scher RL, Richtsmeier WJ, Hars V, George SL, Huang AT, Prosnitz LR. Hyperfractionated irradiation with or without concurrent chemotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 1998; 338:1798. PMID: 9632446.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download