This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

We present the case of a woman on whom a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) was performed through the sinus tract of a previous surgical gastrostomy for supraglottic obstructing malignancy. Five years after the induction of the surgical gastrostomy, she experienced a peristomal leakage, leading to severe necrotizing fasciitis, with skin irritation and inflammation. Despite extensive treatment to heal the abdominal wall close to the feeding tube, it recurred 3 months later, without any obvious cause. It was thus decided to perform a new gastrostomy in a nearby normal skin area, but, since it was totally impossible for the endoscope to be passed by mouth, due to obstruction, the sinus tract of the gastrostomy was used to facilitate endoscope insertion into the stomach for a new PEG.

Go to :

Keywords: Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy, Head and neck malignancy, Surgical gastrostomy, Peristomal leakage, Gastric fistula

INTRODUCTION

Feeding through a gastrostomy has become the most accepted method for patient support, in any case of long- or medium long-term need for enteral nutrition. From the time of the first percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG), as early as 1985, endoscopic gastrostomy placement has almost totally replaced surgical, due to its simplicity and the avoidance of general anaesthesia. However, in some cases, such as neck or esophageal malignancies, where a severe stricture does not allow the passage of the gastroscope, laparotomy is needed. Alternatively, a gastric feeding tube can be introduced by means of a laparoscopy, or by radiology, the main criterion for the election of the procedure being the experience of the operator.

1

We present herein the case of a woman who underwent a PEG, after the endoscope being inserted through the sinus tract of a previously performed surgical gastrostomy for advanced, supraglottic obstructing malignancy.

Go to :

CASE REPORT

A 70-year old female was re-admitted to our ward for a second peristomal leakage episode, leading to severe necrotizing fasciitis and extended dermatitis and inflammation around a gastrostomy tube over a 3-month period.

Five years earlier, the patient had been subjected to a surgical gastrostomy for feeding after the diagnosis of a neck malignancy causing a supraglottic stenosis; thereafter, she received both water and enteral nutrition by this route with no problem. Three months earlier, she had been admitted for severe peristomal inflammation due to excessive leakage around the gastrostomy tube. She was treated by parenteral nutrition, somatostatin and proton pump inhibitors to inhibit the secretions and control the acidity, while the tube was initially put into external drainage. Barrier creams (Conveen Critical Barrier; Coloplast A/S, Thessaloniki, Greece) and skin protectants containing silver (Biatain Ag; Coloplast) were applied to the surrounding skin, and 6-days later the 22 Fr gastrostomy tube was removed to allow the tract to partially close. After a total of 10-days of treatment, a new 18 Fr gastrostomy tube of smaller caliber (Tri-Funnel, Replacement Gastrostomy Tube; Bard, Salt Lake City, UT, USA) was inserted percutaneously through the same site, now considerably shrunk. The peristomal skin was also well healed and so the patient was switched to enteral nutrition through the new tube, and 2 days later was discharged from the hospital, after being advised to use skin barriers around the stoma.

Three months thereafter, she was again admitted to be treated as previously, as she again presented suffering a more pronounced irritation with signs of focal skin necrosis. However, the recurrence of the same severe complication with no prominent cause (diabetes, immunosupression, malnutrition, and adjuvant chemo/radiotherapy) after a short time and long after gastrostomy construction was a cause for discussion and it was decided to perform a new gastrostomy at a different site. Since the patient has a severe supraglottic stenosis due to malignancy (dysphagia 4), the peroral endoscopic route was totally restricted, and we thus, decided to try endoscopically through the sinus of the current stoma.

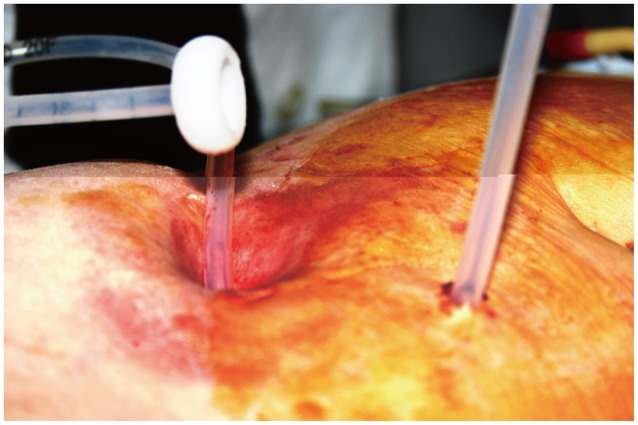

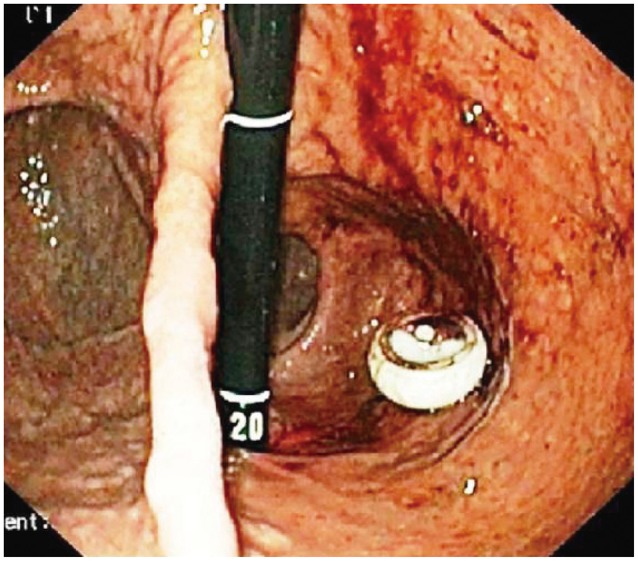

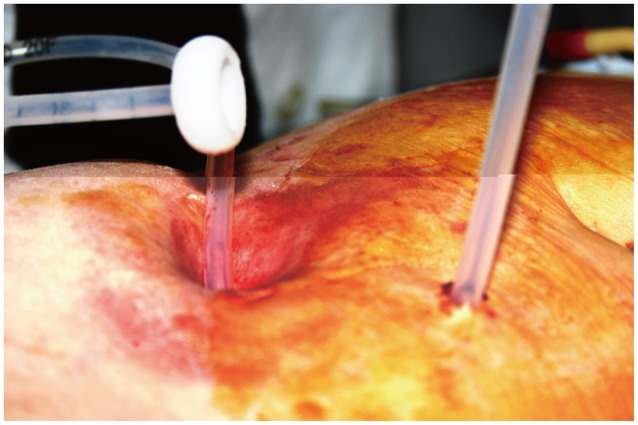

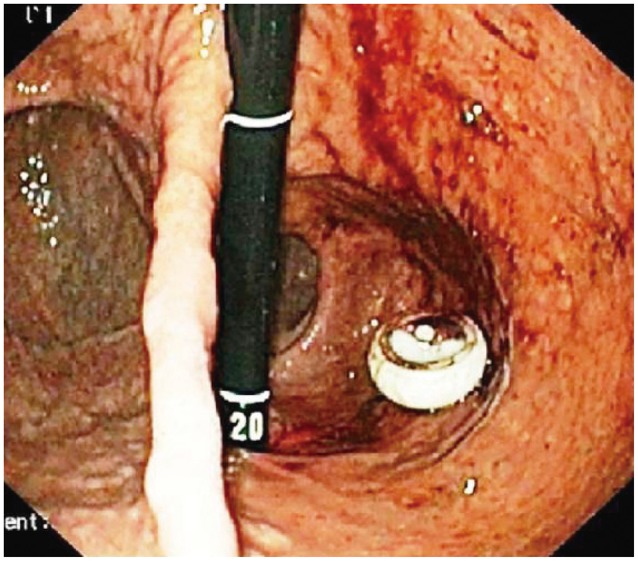

Under light midazolam sedation, dilatation of the sinus tract was initially performed with a controlled radial expansion balloon (CRE, Boston Scientific International S.A., Nanterre Cedex, France) and thereafter the Olympus GIF Q165 gastroscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan)-with a distal and outer diameter of 9.2 mm-was inserted into the stomach through the enlarged opening of the existing gastrostomy tract. After identification of the stomach anatomical signs, transillumination was performed and a new point was selected-as far away as possible from the existing stoma-for needle puncture. A thread was then carried forward by needle lumen into the stomach, delivered by means of grasping forceps through the working channel of the endoscope and exteriorized from the former gastrostomy stoma. The new gastrostomy tube was then attached to this thread, and the thread pulled through the new puncture site (

Figs. 1,

2). The procedure terminated successfully and the patient returned to the surgical ward with a new PEG. The old sinus tract was allowed to heal, as previously. Three days later, the old tract was totally closed and the skin irritation was healed. The patient was discharged with a new functioning gastrostomy.

| Fig. 1Extracorporeal view of the two stomas being in a distance of 10 cm away. The new gastrostomy tube, already attached to the thread, is pulled through the new puncture site.

|

| Fig. 2Endoscopic view of the two stomas being in the gastric antrum. After termination of the procedure, the gastroscope re-inserted through the old stoma for inspection and photography; the internal dome of the new gastrostomy is seen protruded through the new stoma. In the left part gastric fundus and angle are prominent.

|

Go to :

DISCUSSION

One of the most common complications after a tube placement into hollow viscera is that of peristomal leakage, reported in 3% to 36% of the procedures performed. This complication might lead from simple skin irritation, to severe inflammation, infection and tissue necrosis, the severity depending on the patient's accompanying pathology; individuals with diabetes, malnutrition or immunosuppression are more likely to suffer sinus tract mishealing and thus peristomal leakage, and its consequences.

2,

3,

4,

5

The rareness of the present case based on the fact that this complication occurred 5 years after a surgically performed gastrostomy, with no prominent causes to affect the already healed sinus tract. In addition to which, although the patient was treated properly, in order to reduce both the gastric acidity and the gastric contents and the skin was protected by skin barriers, the achieved healing lasted only briefly, and 3 months later a recurrence occurred.

One idea would be to allow the sinus track to be totally closed, with no feeding tube

in situ, and a new PEG performed. However, in our case, the peroral endoscopic route was totally restricted, due to a total malignant obstruction. Laparoscopic performance would be another option, but it was rejected because of the history of previous surgical gastrostomy and the adherence of the stomach to the abdominal wall, as well as for the need for general anaesthesia. Bibliographic references to a method of blind-under X-ray control-stomach puncture

1 and tube insertion by the "push" technique was also rejected, due to our lack of experience with this technique. Since our team has very considerable experience in endoscopy, it was a challenge for us to use the sinus track for the insertion of the endoscope into the stomach to perform an intervention. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, this would be the first case of the sinus track being used for PEG performance.

The first step was to dilate the sinus track by a hydrostatic, controlled radial expansion balloon. Although the gastroscope was inserted and passed without difficulty, this procedure does involve two possible problems: first, that the stomach is so narrow, due to the exact point of the previous stoma in relation to the major or minor curvature, that the endoscope is unable to retroflex in order to "see" the inferior gastric wall; and second, the area that is actually visible after retrovision, denies transillumination, to secure the point for needle puncture. In our case it appears that neither of these problems occurred.

A third problem would be the direction of thread with the attached gastrostomy tube. In normal conditions the inserted thread-by means of the needle into the stomach through the inferior wall of the viscera-is in line with its other end, coming out of the mouth. The traction force applied at the visceral end of the thread-in order to pull the gastrostomy tube from the mouth through the esophagus to the stomach- is thus applied in an almost straight line. In our case, on the other hand, we had a thread both inserted and coming out through the inferior wall of the viscera, the two points being at a distance of 10 cm, the two ends of the thread being parallel so that the force applied for gastrostomy tube traction involved an angle of no more than 20 degrees, making the traction difficult.

In conclusion, apart from the above mentioned problems, the use of the sinus tract of a previous gastrostomy for the insertion of a gastroscope, should it be necessary to perform a further gastrostomy at a new point, seems to be a simple, safe and effective procedure, giving the patient the opportunity to avoid sedation and more complicated procedures.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download