Abstract

Bezoars are retained masses of ingested materials accumulating within the gastrointestinal track. While gastric bezoars are often observed, duodenal bezoars are rarely reported. A 77-year-old man who had frequently consumed persimmons and had never undergone gastric surgery had symptoms of epigastric pain and early satiety for 10 days. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy showed many diospyrobezoars in a severely distended duodenal bulb, otherwise known as megaduodenum. The patient's treatment consisted of repeated endoscopic removal of the bezoars by using a retrieval net.

Bezoars are masses of undigested or partially digested materials in the gastrointestinal tract and are often observed in the stomach. Owing to the presence of the pyloric sphincter, gastric bezoars are generally retained in the stomach.1 However, bezoars can be observed in the small bowel in patients who undergo gastric surgery.

We report the case of a 77-year-old man who had never undergone gastric surgery and presented with diospyrobezoars in a severely distended duodenal bulb.

A 77-year-old man presented to a gastroenterology outpatient clinic with epigastric pain, dyspepsia, and early satiety lasting 10 days after the consumption of persimmons. He had undergone medical treatment for ulcers in the large duodenal bulb 13 years earlier. His medical history was unremarkable, except that he had recently consumed digestive medicine, purchased from a pharmacy, for intermittent indigestion. He had no known comorbidities, had not undergone previous gastrointestinal operation, and had no family history related to these symptoms. A physical examination revealed mild tenderness in the epigastric area. His heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate were all within the normal ranges.

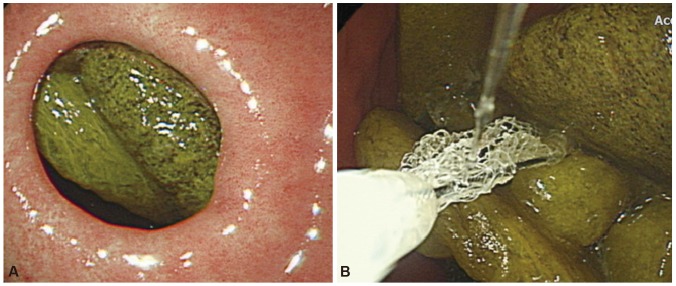

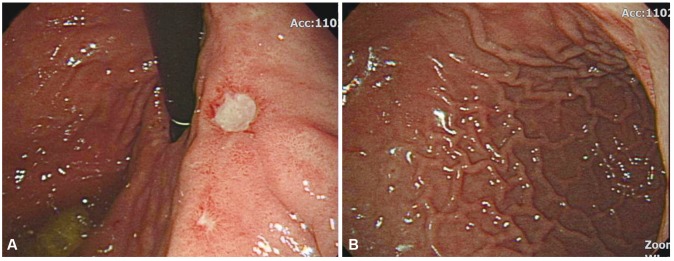

Before visiting our clinic, the patient had undergone esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) at another clinic, which revealed duodenal ulcers and many bezoars in the distended duodenal bulb. As he did not show any signs of intestinal obstruction, he was instructed to drink sufficient amounts of water and Coca-Cola before endoscopic examination. EGD was performed again to obtain an accurate diagnosis and initiate appropriate treatment, and it showed a small amount of undigested food materials in the stomach. The endoscope was passed through the pyloric ring, and it showed multiple bezoars and two ulcers in the dilated duodenal bulb (Fig. 1A). There were approximately 30 bezoars, each measuring <4 cm in diameter. We managed to successfully extract the bezoars from the duodenal bulb by using a retrieval net (Fig. 1B). When the endoscope was turned to view the pylorus in the lumen of the distended duodenal bulb, it looked like the cardia of the stomach (Fig. 2A). Because of the distention of the duodenal bulb, the endoscope could not be passed into the distal part of the distended duodenum, which formed a loop (Fig. 2B). We suspected that the distended duodenal bulb was a herniated stomach. After pulling the endoscope out of the pyloric ring, we identified the true cardia of the stomach, which was normal in shape. Subsequently, the bezoars were removed endoscopically without any complications. The patient was instructed to stop consuming foods that included high concentrations of soluble tannins and to use proton pump inhibitors for treating the duodenal ulcers.

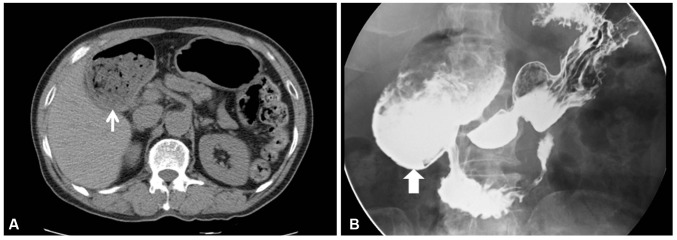

A week after the endoscopic removal of the bezoars, the patient visited our clinic again and reported that his epigastric pain had improved considerably. He underwent radiological examination to assess the improvement in the distended duodenal bulb. Computed tomography (CT) gastrography showed that the proximal duodenal portion was distended and a mass of food material was present in the lumen (Fig. 3A). There was no abnormal wall thickening or luminal obstruction at the distal part of the duodenum. Upper gastrointestinal (UGI) contrast study showed a movable mass-like lesion in the severely distended proximal duodenal portion and gastroesophageal reflux. Passage disturbance or loss of peristalsis was not observed (Fig. 3B). The patient did not experience epigastric pain after the bezoars were removed and after he stopped consuming persimmons, although the follow-up radiological examination showed that the duodenal bulb remained distended. Follow-up endoscopy was not performed because of patient refusal. The patient stopped consuming dried persimmons and continued receiving treatment with proton pump inhibitors and prokinetics.

Bezoars are hard masses of undigested materials in the alimentary tract. Their incidence is relatively low at approximately 0.4% in the general population.2 Bezoars can be classified into several types on the basis of their main components. Phytobezoars are the most common type of bezoars, which are composed of undigested vegetable and fruit fiber. Trichobezoars are a type of bezoars that are composed primarily of hair. Pharmacobezoars are composed of undigested medications. Diospyrobezoars are a subtype of phytobezoars that are caused by ingesting persimmons, which contain tannins called shiboul. In the presence of gastric acid, high concentrations of tannins can undergo polymerization to form a coagulum composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, and protein, which is the basis of the bezoars. This cluster undergoes dehydration and becomes harder, leading to the formation of diospyrobezoars.3

Several predisposing factors for bezoar formation have been reported, which include altered gastrointestinal motility or anatomy, dehydration, use of anticholinergic agents and opiates, and ingestion of high concentrations of soluble tannins. The most common predisposing factor for bezoar formation is a history of gastric surgery.1 Systemic diseases such as diabetes mellitus and hypothyroidism have also been reported to be predisposing factors for bezoar formation caused by delayed gastric emptying.3 Although most bezoars form in the stomach, they can occur anywhere in the gastrointestinal tract. Small bowel bezoars usually occur because of the migration of gastric bezoars, although it is possible for bezoars to form primarily in the small bowel.3 In the presence of predisposing factors such as a history of gastric surgery, diabetes mellitus, end-stage renal disease, or hypothyroidism, large-sized bezoars can form at rare sites in the gastrointestinal tract in some cases.1 Duodenal diospyrobezoars, such as those observed in the present case, are very rare. They occur in the duodenal bulb in the absence of any common predisposing factors such as a history of gastric surgery or diabetes mellitus, except the consumption of persimmons. In the present case, endoscopic and radiological examination of the patient showed a severely distended duodenal bulb without any luminal narrowing or mechanical obstruction in the distal small bowel. These anatomical abnormalities of the patient's gastrointestinal tract may have contributed to the retention of undigested remains of persimmons and to the formation of diospyrobezoars.

In several previous cases, a distended duodenum was described as a megaduodenum, which was caused by a congenital intestinal obstruction such as duodenal atresia or developed after surgery of the lower duodenum.45 Idiopathic megaduodenum, also known as congenital megaduodenum, is defined as a huge dilatation confined to the duodenum without mechanical obstruction.6 Zhang et al.7 reported data on four patients with idiopathic megaduodenum. All four patients were children under the age of 12 years and had undergone operation for relieving symptoms of abdominal distension, nausea, vomiting, and malnutrition. These patients had a massively dilated duodenum with a slightly thickened duodenal wall, but no obvious mechanical obstruction was observed on examination.7 In rare cases, a megaduodenum can be secondary to visceral myopathy or neuropathy associated with polymyositis and may result from the absence of the parasympathetic ganglion cells in Auerbach's plexus.68 A megaduodenum may be misdiagnosed and treated improperly owing to the lack of adequate knowledge and clinical experience.7 In the present case, the patient had no anatomical abnormalities, except for a severely distended duodenal bulb, or passage disturbances of the UGI tract. Pathologic examination of the distal part of the distended duodenum could not be performed because the endoscope could not pass into the distal duodenum. Although we could not perform full-thickness biopsies and manometric examination of the megaduodenum, it was less likely that the megaduodenum was caused by visceral myopathy due to an autoimmune disease such as systemic sclerosis or polymyositis and intestinal pseudo-obstruction, as UGI contrast study showed that the patient had normal duodenal peristalsis and had no clinical manifestations of autoimmune diseases.910

EGD is a first-line diagnostic modality for detecting bezoars, which allows direct visualization and helps to determine the appropriate therapeutic intervention. Other available diagnostic methods include UGI contrast series, abdominal ultrasonography, and CT.1 Bezoars in filling defects can be detected using UGI series to identify passage problems and deformities of the gastrointestinal tract. CT scans may provide information about anatomical abnormalities around the bezoars in the gastrointestinal tract. In the present case, EGD was used to obtain the initial diagnosis and initiate appropriate treatment.

Bezoars need to be removed because if left untreated, they can cause not only symptoms such as epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting, weight loss, and abdominal distension but also the obstruction, perforation, and bleeding of the gastrointestinal tract.11 Some small and soft bezoars can be treated conservatively with nasogastric lavage. However, endoscopic fragmentation is the treatment of choice for most gastroduodenal bezoars.1 Various endoscopic methods and instruments for treatment have been reported, including biopsy forceps, basket lithotripsy, polypectomy snare, and argon plasma beam.12 Some studies have reported that Coca-Cola can be used to soften and shrink bezoars.113 After treatment with Coca-Cola, endoscopic fragmentation can be performed easily. In patients with bowel obstruction, early surgery is required because they rarely improve with conservative management.3 Although treatment for megaduodenum is not yet well established, several studies have reported successful treatment with surgery such as duodenoplasty or duodenojejunostomy.714 In the present case, bezoars were successfully removed endoscopically by using a retrieval net. Although a follow-up radiological study showed that the patient still had a distended duodenal bulb, he did not experience epigastric pain after the endoscopic bezoar removal and refused to undergo further invasive examination and treatment owing to his advanced age. He was advised to avoid excessive consumption of persimmons, dehydration, and any medications that could reduce gastrointestinal tract motility.

In conclusion, this case is unique for its unusual presentation of bezoars in a severely distended duodenal bulb without any obstruction or luminal narrowing of the distal part of the duodenum. Our patient did not have any known predisposing factors such as a history of gastric surgery or diabetes mellitus, except that he had consumed persimmons. The duodenal bezoars probably occurred because of the patient's frequent consumption of persimmons in the presence of a megaduodenum. Furthermore, this case is meaningful in that it shows asymptomatic megaduodenum might be observed without any invasive management.

References

1. Yang JE, Ahn JY, Kim GA, et al. A large-sized phytobezoar located on the rare site of the gastrointestinal tract. Clin Endosc. 2013; 46:399–402. PMID: 23964339.

2. McKechnie JC. Gastroscopic removal of a phytobezoar. Gastroenterology. 1972; 62:1047–1051. PMID: 5029071.

3. de Toledo AP, Rodrigues FH, Rodrigues MR, et al. Diospyrobezoar as a cause of small bowel obstruction. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2012; 6:596–603. PMID: 23271989.

4. Lytras D, Olde-Damink SW, Imber CJ, Hatfield A, Amin Z, Malago M. Duodenal web in an adult presenting with acute pancreatitis and acquired megaduodenum: report of a case. Surg Today. 2011; 41:426–429. PMID: 21365431.

5. Karstensen J, Raahave D, Kirkegaard P. Mega-duodenum and constipation after surgery for congenital atresia of the jejunum. Ugeskr Laeger. 2011; 173:1808–1809. PMID: 21689512.

6. Barnett WO, Wall L. Megaduodenum resulting from absence of the parasympathetic ganglion cells in Auerbach's plexus; review of the literature and report of a case. Ann Surg. 1955; 141:527–535. PMID: 14362386.

7. Zhang XW, Abudoureyimu A, Zhang TC, et al. Tapering duodenoplasty and gastrojejunostomy in the management of idiopathic megaduodenum in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2012; 47:1038–1042. PMID: 22595598.

8. Mansell PI, Tattersall RB, Balsitis M, Lowe J, Spiller RC. Megaduodenum due to hollow visceral myopathy successfully managed by duodenoplasty and feeding jejunostomy. Gut. 1991; 32:334–337. PMID: 1901564.

9. Boeckxstaens GE, Rumessen JJ, de Wit L, Tytgat GN, Vanderwinden JM. Abnormal distribution of the interstitial cells of cajal in an adult patient with pseudo-obstruction and megaduodenum. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002; 97:2120–2126. PMID: 12190188.

10. Kudoh K, Shibata C, Funayama Y, et al. Gastrojejunostomy and duodenojejunostomy for megaduodenum in systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma: report of a case. Dig Dis Sci. 2007; 52:2257–2260. PMID: 17420947.

11. Singh SK, Marupaka SK. Duodenal date seed bezoar: a very unusual cause of partial gastric outlet obstruction. Australas Radiol. 2007; 51(Spec No.):B126–B129. PMID: 17875133.

12. Lee BJ, Park JJ, Chun HJ, et al. How good is cola for dissolution of gastric phytobezoars? World J Gastroenterol. 2009; 15:2265–2269. PMID: 19437568.

13. Ha SS, Lee HS, Jung MK, et al. Acute intestinal obstruction caused by a persimmon phytobezoar after dissolution therapy with Coca-Cola. Korean J Intern Med. 2007; 22:300–303. PMID: 18309693.

14. Nichol PF, Stoddard E, Lund DP, Starling JR. Tapering duodenoplasty and Roux-en-Y duodenojejunostomy in the management of adult megaduodenum. Surgery. 2004; 135:222–224. PMID: 14739858.

Fig. 1

Endoscopic findings. (A) Bezoars were observed through the pyloric ring. (B) Bezoars were removed using a retrieval net.

Fig. 2

Endoscopic findings. (A) When the endoscope was turned to the pylorus in the distended duodenal bulb after the endoscopic removal of the bezoars, the pylorus looked like the cardia of the stomach. (B) As the duodenal bulb was severely distended, the upper gastrointestinal endoscope could not pass into the distal duodenum.

Fig. 3

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) gastrography and upper gastrointestinal contrast study findings. (A) Abdominal CT gastrography showed that the proximal duodenal portion (arrow) was distended and a small amount of undigested food materials was present in the lumen a week after the endoscopic removal of the bezoars. (B) Upper gastrointestinal contrast study showed a movable mass-like lesion in the severely distended proximal duodenal portion (arrow) a week after the endoscopic removal of the bezoars.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download