Abstract

Background/Aims

There is a growing emphasis on quality management in endoscope reprocessing. Previous surveys conducted in 2002 and 2004 were not practitioner-oriented. Therefore, this survey is significant for being the first to target actual participants in endoscope reprocessing in Korea.

Methods

This survey comprised 33 self-filled questions, and was personally delivered to nurses and nursing auxiliaries in the endoscopy departments of eight hospitals belonging to the society. The anonymous responses were collected after 1 week either by post or in person by committee members.

Results

The survey included 100 participants. In the questionnaire addressing compliance rates with the reprocessing guideline, the majority (98.9%) had a high compliance rate compared to 27% of respondents in 2002 and 50% in 2004. The lowest rate of compliance with a reprocessing procedure was reported for transporting the contaminated endoscope in a sealed container. Automated endoscope reprocessors were available in all hospitals. Regarding reprocessing time, more than half of the subjects replied that reprocessing took more than 15 minutes (63.2%).

Go to :

Gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy is an important tool for diagnosing and treating disorders of the GI tract. With the extension of the National Cancer Screening Program, the frequency of endoscopic examination has increased. Endoscopic equipment is not disposed of after use. Most of the time, it will be reused in another patient, and therefore requires reprocessing. However, the complex structure of an endoscope, the narrow biopsy channel, the presence of various accessories, and the humid environment during use increase the chance of contamination by infectious organisms.

Most cases of endoscopy-mediated infection can be attributed to inappropriate reprocessing.1,2,3,4 However, lack of data hinders any conclusion of a causal relationship between endoscopy and pathogen transmission. There is no specific reported case of an infection caused by endoscopic examination in Korea. In a recent review of the published medical literature and the Food and Drug Administration database, the reported incidence of an infection caused by endoscopic examination was only 35 cases in the last decade, which is extremely low considering the estimated 340 million procedures performed over this period.5 However, a causal relationship between an endoscopy procedure and pathogen transmission is difficult to prove for several reasons including the long latent period and subclinical symptoms. The actual prevalence of infection transmission may be higher.6,7

Guidelines for reprocessing flexible endoscopes have been published in many countries to prevent endoscope-mediated pathogen transmission.8,9,10,11 However, their complexity and the high cost of reprocessing can reduce compliance. In 1995, the Korean Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy established endoscopic cleaning and disinfection guidelines to prevent endoscopic examination-mediated transmission paths of infection. The first and second revised guidelines were released in August 2009 and August 2012, respectively. There has been no standard method of evaluating the reprocessing procedure. In some countries, surveys on endoscope reprocessing were conducted.12,13,14,15,16,17 In Korea, endoscope reprocessing surveys were implemented in 2002 and 2004, but these were not practitioner-oriented surveys.18 Therefore, we undertook an endoscope reprocessing survey targeting actual practitioners to determine whether the reprocessing guidelines have been properly followed and to determine the precise current status of endoscope reprocessing.

Go to :

A survey commissioned by the Disinfection Management Committee of the Korean Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy was conducted during a 1-week period starting on June 3, 2013. The survey targeted nurses and nursing auxiliaries from the endoscopy units of eight secondary or tertiary hospitals belonging to the society. The initial content of the survey was developed based on the previous endoscope reprocessing surveys conducted in 2002 and 2004 as well as those conducted in other countries. Since then, the content has been modified by the committee. The final survey comprised 33 self-filled questions and was distributed to 101 employees working in the various digestive endoscopy units by committee members (Appendix 1). The anonymous responses were collected after 1 week either by post or in person by committee members. All statistical analyses were performed with the statistical program R version 2.9.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). For detailed analysis, differences were compared using the chi-square test and judged statistically meaningful at p<0.05.

Go to :

Overall, 100 of the 101 nurses and nursing auxiliaries responded.

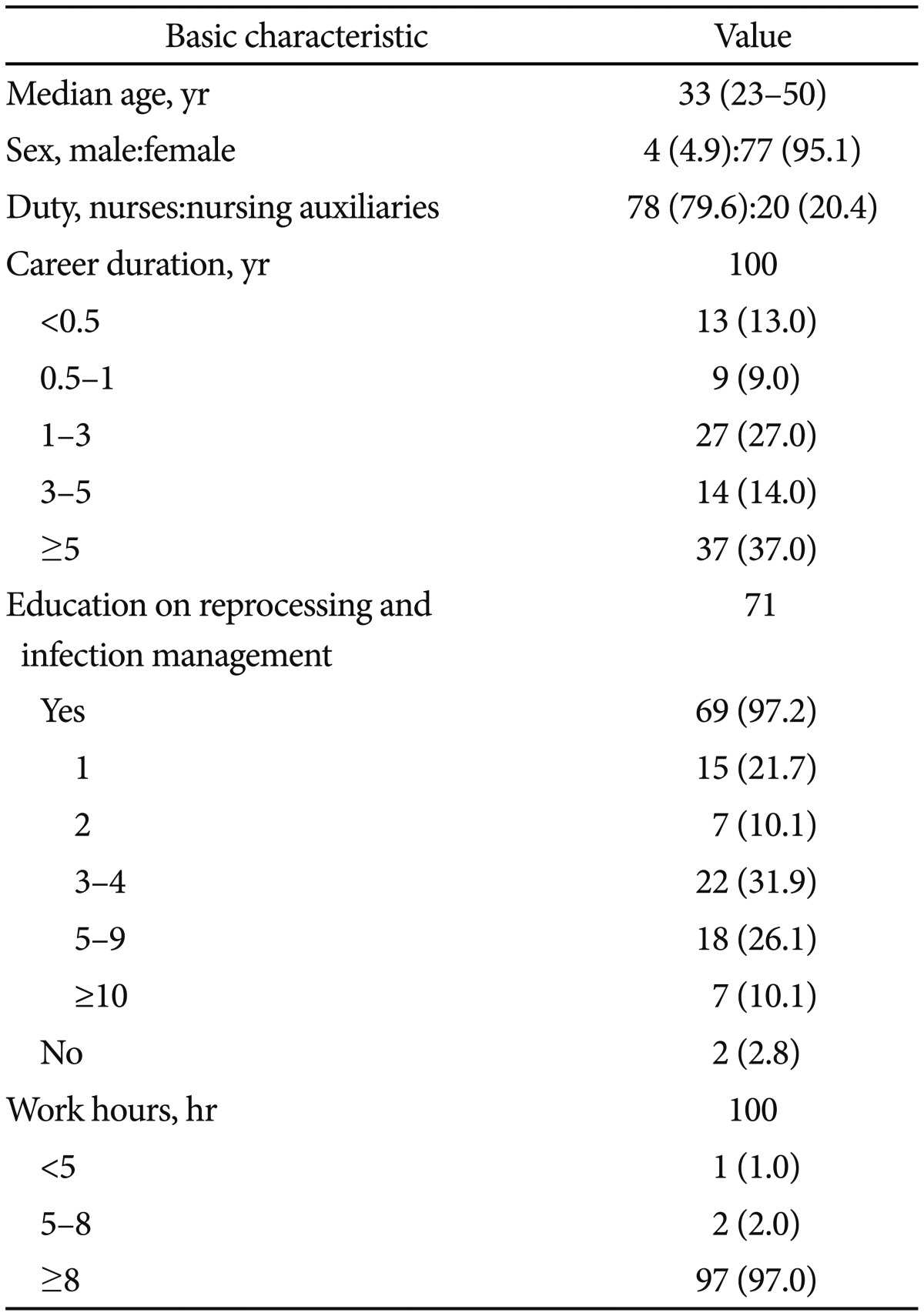

The median subject age was 33 years, and most (95.1%) were female (exclusive of 19 non-respondents). Among 98 respondents, 78 were nurses (79.6%) and 20 were nursing auxiliaries (20.4%). Seventy-eight (78.0%) were working for more than 1 year, with 37 (37.0%) having worked more than 5 years. Concerning knowledge of cleaning and disinfection of the endoscope and infection control, 98 (98.0%) replied that they were educated on these topics. Most respondents (97.0%) replied that they worked for more than 8 hours per work shift (Table 1).

Concerning the number of endoscopy center employees, 94 respondents (94.0%) indicated there were more than five employees in their centers, with 65 (65.0%) working in a center with more than 10 employees. According to most respondents (88.0%), the disinfection and procedure areas were separate. In all, 93 subjects (93.0%) replied that their center had more than three automated endoscope reprocessors (AERs), with 58 (58.0%) working in a center with more than six. Concerning the average number of endoscopic procedures per day, 98 (98.0%) replied that their center performed more than 30 procedures per day, with 56 subjects (56.0%) indicating a daily rate exceeding 100 procedures. In terms of the average number of esophagogastroduodenoscopic examinations per day, 63 respondents (74.1%) replied that their center performed more than 30 procedures. Concerning the average number of colonoscopic examinations per day, 59 respondents (69.4%) replied that there were more than 30 procedures. Concerning the average number of therapeutic endoscopies per day, 72 subjects (93.5%) indicated that there were more than five procedures. Regarding the number of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography procedures, 53 subjects (70.7%) replied that there were fewer than five. Finally, concerning the number of endoscopic ultrasonography procedures, 45 survey responders (64.3%) indicated there were less than five procedures (Table 2).

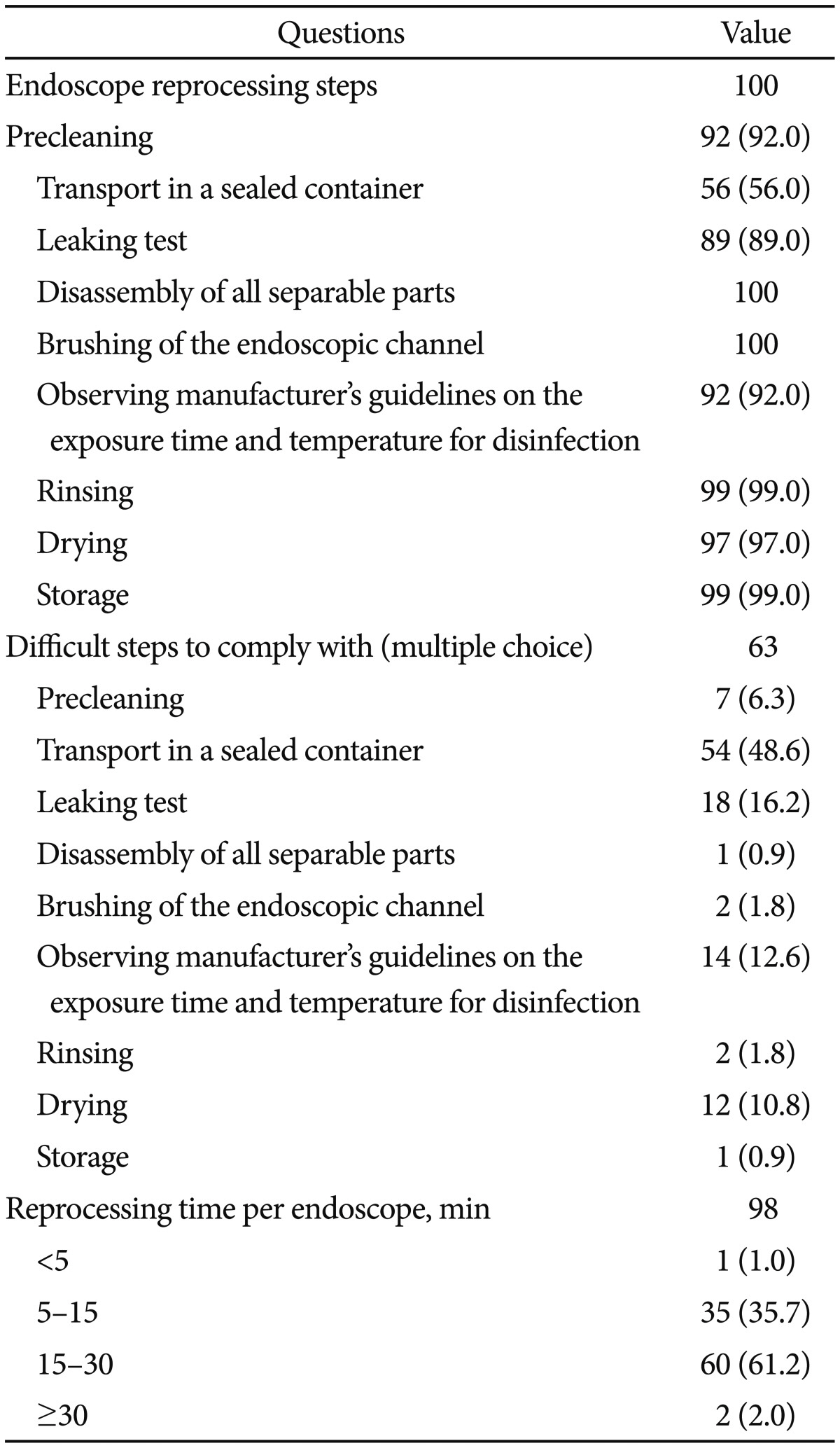

There were 98 responders to questions regarding compliance with the reprocessing guidelines. Of these, 51 (52.0%) indicated full compliance with the guidelines and 46 (46.9%) indicated making an effort to comply. All 100 participants replied to questions concerning the steps of endoscope reprocessing. Transport of a contaminated endoscope in a sealed container to the disinfection area had the lowest compliance rate (56%), followed by performing a leaking test (89%) and observing the manufacturer's guidelines regarding the exposure time and temperature for disinfection (92%). There were 63 responses to multiple choice questions on reprocessing procedures that were practically difficult to perform. Again, transport of the contaminated endoscope in a sealed container to the disinfection area had the lowest compliance (48.6%). We compared compliance rates for this step (i.e., contaminated endoscope transport) between hospitals with >100 vs. <100 average daily endoscopic examinations, and found no significant difference in compliance (56.8% vs. 55.4%, p=0.523). Thus, the cause of noncompliance is not simply the high number of endoscopic examinations, and attention should be given to further increase compliance rates in the future. The leaking test (16.2%) had the second lowest compliance, and observing the manufacturer's guidelines regarding the exposure time and temperature for disinfection (12.6%) had the third lowest compliance. Reported endoscope reprocessing times were <5 minutes in one case (1.0%), between 5 and 15 minutes in 35 cases (35.7%), between 15 and 30 minutes in 60 cases (61.2%), and >30 minutes in two cases (2.0%) (Table 3). Reprocessing times did not significantly differ between hospitals with more or less than 100 daily examinations on average (p=0.386). There were 99 responses concerning the reuse of disposable accessories. Of these, 37.4% replied that they reuse the disposable accessories while 62.6% replied that they do not.

Seventy-nine subjects replied to a multiple voting item concerning the reason that the guideline is difficult to perform practically. Thirty-two subjects (35.6%) replied that the number of endoscopic procedures is too high to secure enough time for endoscope reprocessing, eight subjects (8.9%) indicated problems with the medical insurance fee for endoscopic procedures, 39 subjects (43.3%) indicated that money and time were problematic, and 11 subjects (12.2%) indicated that a frequent change of disinfecting staff was a problem.

The item regarding the primary factor needed to ensure observation of the guidelines received 99 responses. The indicated primary factor was raising insurance fees or an arrangement for the reprocessing cost in 50 cases (50.5%), the need for education on endoscope reprocessing as well as job stability in 36 cases (36.4%), thorough observation and control of disinfection processes in five cases (5.1%), increasing the supply of AER in five cases (5.1%), control of the number of endoscopic procedures in two cases (2.0%), and increasing the number of disinfecting staff in one case (1.0%).

There were 97 responses on the quality management of endoscope reprocessing and infection surveillance. Fifty-three subjects (54.6%) replied that they were regularly evaluated both by their hospital and by an external assessment institution, 29 subjects (29.9%) indicated hospital evaluations only, 10 subjects (10.3%) indicated only external assessment, and five subjects (5.2%) replied that they never once received an evaluation. Ninety-eight subjects responded regarding the most effective method of educating employees on reprocessing guidelines. Eighty-three subjects (84.7%) chose a hands-on course, 14 subjects (14.3%) selected a scholarly symposium, and one person (1.0%) preferred receiving online education. No one selected the option of reading a book about disinfection.

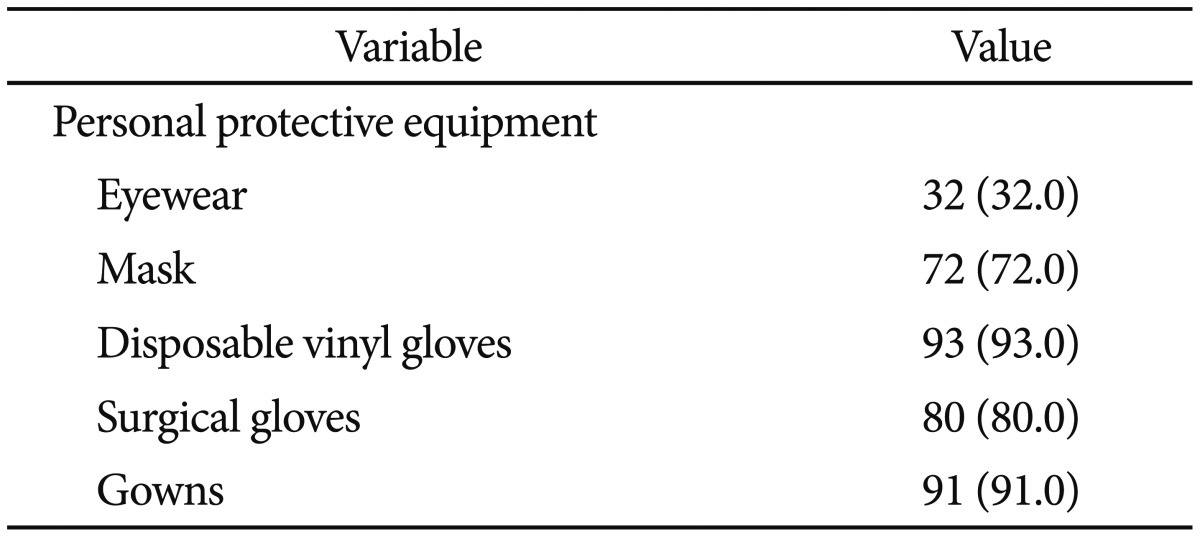

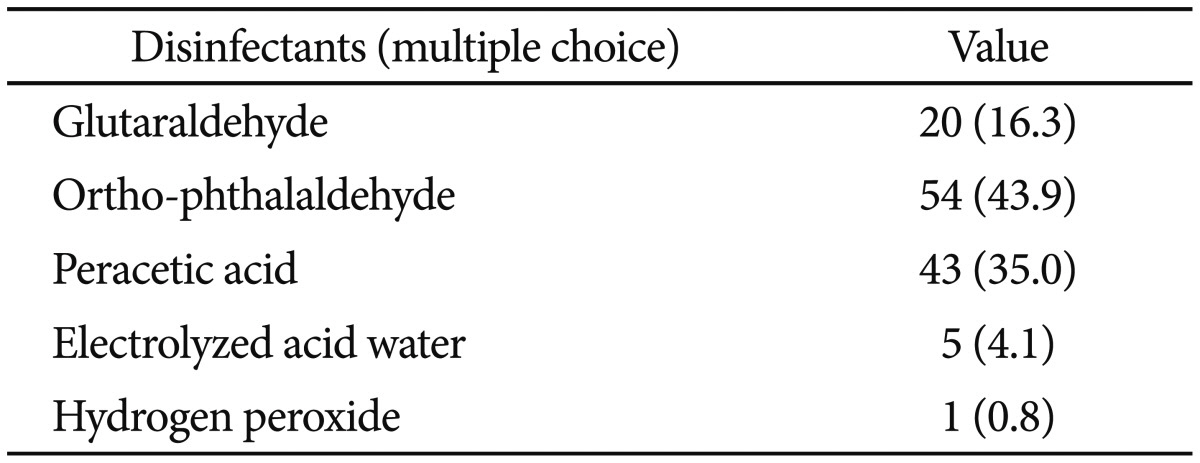

There were 100 replies to the questionnaire on personal protective equipment. The lowest compliance rate was with wearing protective eyewear, with only 32 subjects (32.0%) complying. This was followed by use of a mask (72.0%) and wearing surgical gloves (80%) (Table 4). There were 100 responses regarding occupational hazards. Of these, 96 subjects (96.0%) had experienced headache, backache, or arthralgia. Seventy-four subjects (74.0%) had experienced headache, dizziness, nausea, eye strain, hemorrhage, and skin rash after exposure to disinfectants. The disinfectants used most frequently by 87 respondents as indicated on a multiple choice item were ortho-phthalaldehyde (43.9%) and peracetic acid (35.0%) (Table 5). Fifty-two subjects (52.0%) experienced an infection-related accident caused by a contaminated endoscope or accessories, or an injection needle stick injury.

Go to :

This survey was the first to target nurses and nursing auxiliaries who actually participate in endoscope reprocessing. Prior surveys conducted in 2002 and 2004 queried physicians. Most of the reprocessing processes showed high compliance rates. On the questionnaire item that inquired about the rate of compliance with the reprocessing guidelines, the majority of respondents (98.9%) indicated high compliance, in comparison to 27% and 50% of respondents, respectively, in the 2002 and 2004 surveys.18

Among the several steps involved in endoscope reprocessing, transporting the contaminated endoscope in a sealed container to the disinfection area had the lowest compliance (56.0%) and was selected as the most difficult step to comply with. The compliance rates with this step in the United States and Portugal were 26% and 44%, respectively.12,13 Concerning the endoscopy unit environment, most subjects (88.0%) replied that the disinfection and procedure areas were separate. Compared to the percentages reported in the United States (85%), Portugal (92%), Spain (47%), Italy (12.3%), Germany (80%), and Romania (27.6%), the percentage in our survey is relatively high.12,13,14,15,16,19 AER was available in all hospitals that participated in our survey, compared with 32% and 49% of the hospitals surveyed in 2002 and 2004, respectively.18 On the other hand, surveys conducted in the United States, Portugal, and Italy reported 9.5%, 4%, and 9.1% implementation rates for manual disinfection, respectively. In a survey conducted in Germany, AERs were available in most hospitals, while in Spain, Romania, and China only a respective 23%, 34.5%, and 22.1% had AERs.12,13,14,15,16,17,19 AERs have important roles, such as replacing some manual reprocessing steps or manual disinfection, reducing user exposure to hazardous reprocessing chemicals and contaminated equipment, and highly reliable reprocessing.20 A previous study reported that microorganisms were detected on more than 40% of endoscopes after manual/semi-automatic reprocessing compared with 14% to 16% of instruments after automatic reprocessing.21 Therefore, a high AER penetration rate and an increasing dependency on AERs indicate good quality management as compared with the 2002 and 2004 surveys.18 In addition, questionnaire results regarding the reprocessing time of a single endoscope, indicate an increase in reprocessing time more so than in manual disinfection despite the incremental change in examination numbers. In general, the quality management of endoscopes is good.

Concerning disinfectants, surveys conducted in other countries found that glutaraldehyde was used most often. However, in domestic surveys, ortho-phthaldehyde was used most often (43.9%), followed by peracetic acid (35.0%), glutaraldehyde (16.3%), electrolyzed acid water (4.1%), and hydrogen proxide (0.8%).12,17,22 There are several reasons for the preference of ortho-phthaldehyde or peracetic acid over glutaraldehyde in Korea. First, glutaraldehyde has a relatively lengthy immersion time compared with other disinfectants.23 Second, glutaraldehyde may cause serious irritation to the eyes or respiratory system, and can cause allergic reactions of the skin, conjunctiva, nose, and pharynx.24,25 Therefore, a reprocessing area must include a ventilator to avoid vapor inhalation. These are significant disadvantages to the endoscope reprocessing process in Korea, where a relatively high number of endoscopic examinations are done compared with similar-sized hospitals in other countries. Most subjects (96.0%) replied that they have experienced occupational hazards. Concerning personal protective equipment, the majority of subjects replied that they wore most of the personal protective equipment, with the exception of eyewear. The latter is a concern. Moreover, surveys on occupational hazards should target all practitioners in endoscopy units, including doctors.

The qualitative evaluation and education by the Korean Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy aims to improve the quality management of endoscope reprocessing. However, several problems, such as reuse of disposable accessories, transport of the contaminated endoscope in a sealed container, and the wearing of eyewear need improvement. Most subjects (87.8%) selected financial problems such as the medical insurance fee for endoscopic procedures and the high number of endoscopic examinations as the two most common reasons for difficulty in complying with the guidelines. More than half of the subjects (50.5%) replied that a higher medical insurance fee for endoscopic procedures or a newly introduced disinfection cost were needed to comply with the guidelines, while others replied that education, employment security, or periodic surveillance were needed. Reconsideration of the endoscopic examination fee is needed for future quality management to resolve these problems. Moreover, periodic surveillance and education directed towards practitioners should be continued.

This survey has some limitations. Since it targeted hospitals that are members of the Disinfection Management Committee under the Korean Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, the present survey excluded primary clinics. Compliance with the endoscope reprocessing procedure could be higher than is apparent in Korea. However, there are financial hurdles to satisfying all the conditions such as labor costs, purchase of the AER, and reuse of disposable accessories designed for single-time use that can lower the quality of endoscope reprocessing.

In conclusion, this survey demonstrates that the quality management of endoscope reprocessing has improved compared with surveys conducted in 2002 and 2004. To improve endoscope reprocessing quality management, medical insurance fees should be raised and adequate endoscope reprocessing should be bolstered by the periodic surveillance of healthcare quality and continuous education. A national survey that includes primary clinics will be necessary.

Go to :

Acknowledgments

We would like to especially thank Hoon Jai Chun, director of the Disinfection Management Committee under the Korean Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, for supporting this research survey, as well as the endoscopy center practitioners from each hospital who voluntarily participated in this survey.

Go to :

References

1. Spach DH, Silverstein FE, Stamm WE. Transmission of infection by gastrointestinal endoscopy and bronchoscopy. Ann Intern Med. 1993; 118:117–128. PMID: 8416308.

2. Lisgaris MV. The occurrence and prevention of infections associated with gastrointestinal endoscopy. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2003; 5:108–113. PMID: 12641995.

3. Wu H, Shen B. Health care-associated transmission of hepatitis B and C viruses in endoscopy units. Clin Liver Dis. 2010; 14:61–68. PMID: 20123440.

4. Alvarado CJ, Stolz SM, Maki DG. Nosocomial infections from contaminated endoscopes: a flawed automated endoscope washer. An investigation using molecular epidemiology. Am J Med. 1991; 91(3B):272S–280S. PMID: 1928177.

5. Nelson DB. Infectious disease complications of GI endoscopy: part II, exogenous infections. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003; 57:695–711. PMID: 12709700.

6. Nelson DB, Muscarella LF. Current issues in endoscope reprocessing and infection control during gastrointestinal endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2006; 12:3953–3964. PMID: 16810740.

7. Hong KH, Lim YJ. Recent update of gastrointestinal endoscope reprocessing. Clin Endosc. 2013; 46:267–273. PMID: 23767038.

8. Walter VA, DiMarino AJ Jr. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy-Society of Gastroenterology Nurses and associates endoscope reprocessing guidelines. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2000; 10:265–273. PMID: 10683213.

9. Systchenko R, Marchetti B, Canard JN, et al. Guidelines of the French Society of Digestive Endoscopy: recommendations for setting up cleaning and disinfection procedures in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2000; 32:807–818. PMID: 11068843.

10. Wilkinson M, Simmons N, Bramble M, et al. Report of the Working Party of the Endoscopy Committee of the British Society of Gastroenterology on the reuse of endoscopic accessories. Gut. 1998; 42:304–306. PMID: 9536960.

11. Heeg P. Reprocessing endoscopes: national recommendations with a special emphasis on cleaning: the German perspective. J Hosp Infect. 2004; 56(Suppl 2):S23–S26. PMID: 15110119.

12. Moses FM, Lee JS. Current GI endoscope disinfection and QA practices. Dig Dis Sci. 2004; 49:1791–1797. PMID: 15628705.

13. Soares JB, Goncalves R, Banhudo A, Pedrosa J. Reprocessing practice in digestive endoscopy units of district hospitals: results of a Portuguese National Survey. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011; 23:1064–1068. PMID: 21862930.

14. Heudorf U, Exner M. German guidelines for reprocessing endoscopes and endoscopic accessories: guideline compliance in Frankfurt/Main, Germany. J Hosp Infect. 2006; 64:69–75. PMID: 16820248.

15. Frăţilă O, Tanţău M. Cleaning and disinfection in gastrointestinal endoscopy: current status in Romania. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2006; 15:89–93. PMID: 16680240.

16. Brullet E, Ramirez-Armengol JA, Campo R. Board of the Spanish Association for Digestive Endoscopy. Cleaning and disinfection practices in digestive endoscopy in spain: results of a national survey. Endoscopy. 2001; 33:864–868. PMID: 11571683.

17. Zhang X, Kong J, Tang P, et al. Current status of cleaning and disinfection for gastrointestinal endoscopy in China: a survey of 122 endoscopy units. Dig Liver Dis. 2011; 43:305–308. PMID: 21269894.

18. Seol SY, Moon JS, Kae SH, et al. Result report of endoscopic reprocessing survey: 2002 and 2004. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 2005; 30(Suppl 1):109S–118S.

19. Spinzi G, Fasoli R, Centenaro R, Minoli G. SIED Lombardia Working Group. Reprocessing in digestive endoscopy units in Lombardy: results of a regional survey. Dig Liver Dis. 2008; 40:890–896. PMID: 18400569.

20. ASGE Technology Committee. Desilets D, Kaul V, et al. Automated endoscope reprocessors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010; 72:675–680. PMID: 20883843.

21. Bader L, Blumenstock G, Birkner B, et al. HYGEA (Hygiene in gastroenterology: endoscope reprocessing): study on quality of reprocessing flexible endoscopes in hospitals and in the practice setting. Z Gastroenterol. 2002; 40:157–170. PMID: 11901449.

22. Miyajima K, Tabuchi T, Kumagai S. Occupational health of endoscope sterilization workers in medical institutions in Osaka Prefecture. Sangyo Eiseigaku Zasshi. 2006; 48:169–175. PMID: 17062996.

23. Park S, Jang JY, Koo JS, et al. A review of current disinfectants for gastrointestinal endoscopic reprocessing. Clin Endosc. 2013; 46:337–341. PMID: 23964330.

24. Axon AT, Banks J, Cockel R, Deverill CE, Newmann C. Disinfection in upper-digestive-tract endoscopy in Britain. Lancet. 1981; 1:1093–1094. PMID: 6112457.

25. Cowan RE, Manning AP, Ayliffe GA, et al. Aldehyde disinfectants and health in endoscopy units. British Society of Gastroenterology Endoscopy Committee. Gut. 1993; 34:1641–1645. PMID: 8244157.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download